Externsteine

The Externsteine are a distinctive sandstone - rock formation in the Teutoburg Forest and as such a prominent natural landmark of Germany , which under natural and cultural monument stands. The rocks are surrounded by the Wiembecketeich and a park-like area. The Externsteine are located in the area of the town of Horn-Bad Meinberg in the Lippe district in North Rhine-Westphalia . They are assigned special cultural-historical meanings.

Surname

The name of the rock group has been the subject of many publications on the Externsteine to this day. The current spelling Externsteine most likely goes back to the lexicographer Jacob Christoph Iselin . In the interpretations and explanations of the name, the defining word "Exter (n) -" is in the center. Essentially, this is interpreted as a derivation from the Low German dialectal designation of "Egge" for a mountain range ( Osning from Osnegge , Eggegebirge ) and as a derivation from the name of the bird species " Elster ". The basic word "-stein" appears in the oldest documents in the singular to Old Saxon "sten" = "stone, rock"; the following forms are documented chronologically (a selection):

- around 1093, 1380 as "Agistersten"

- 1379 "thon Eghesterensteyn"

- 1571 as the "Egestersteine"

- 1598 "Eggsternstein"

- 1627 "Egerster Stein"

Since Hermann Hamelmann's influential treatise on Westphalian history, published in 1564, the formation has been increasingly referred to as "rupis picarum" = "rock of magpies". The reference to the Elster probably originates as a secondary vernacular connection during the Middle Low German language period from the documented forms such as "egester, egster, exter".

Current scientific research on names (Meineke, Udolph / Beck) assumes the oldest documented form Ag-i-ster- when interpreting the defining word and therefore the compound word . This form shows the Germanic root * ag- = "sharp, pointed, angular" or "stone"; this root is found, for example, in Old Saxon eggia = "sharp edge, sword" and Middle Low German egge = "cutting edge, hem, mountain ridge" and in New High German egge (such as the agricultural implement ). Furthermore, Agister- shows an old -str- derivation, which is particularly derived from -i- or -j- tribes , such as in Germanic * blōstra- , Gothic blōstr , Old High German bluostar = "worship" and in Germanic * gelstra- , Gothic gilstr = "tribute, customs" and Old High German gelstar = "sacrifice".

The defining word in today's name Externsteine is therefore the name "Egge", which is widespread in Westphalia, and specifically in connection with the rock formation the meaning for "a protruding point or a narrow mountain ridge" after its originally pointed and towering shape.

Geographical location

Located in the north-east of North Rhine-Westphalia, in the southern part of the Lippe district, the Externsteine belong to the Horn-Bad Meinberg district of Holzhausen-Externsteine, which is about one kilometer (as the crow flies ) northwest.

In terms of regional geography, the rocks are only about three kilometers northwest of the point where the Teutoburg Forest range , which stretches from northwest to southeast , turns into the Egge Mountains, which run from north to south . To the northwest, the Externsteine merge directly into the rising, wooded slopes of the Bärenstein and, to the southeast, directly into those of the Knickenhagen . The Wiembecke flows directly past the rock group in the catchment area of the Weser and is dammed at the foot of the rocks to form the Wiembecketeich .

geology

The Externsteine consist of Osning sandstone , the material of which originated from the Rhenish mass , while the Lower Cretaceous was deposited in shallow water near the coast on the edge of a large sea that covered a large part of northern Central Europe at that time . The stratigraphic classification of the Externsteine is difficult because no macrofossils have been found in them ; The Lower Alb is assumed to be the most likely time of origin around 110 million years ago.

Caused by the north drift of the African plate , the saxonic clod tectonics , beginning around 70 million years ago, made the previously horizontal rock layers then locally vertical, so that the material on the northeast side of the rocks is older than on the southwest front. Favored by a warm, humid, tropical climate with intense chemical weathering that prevailed in the subsequent period of the Paleogene and Neogene (formerly: Tertiary ) , the rocks received their current, somewhat bizarre-looking shape through erosion . Good to see is the for granite , but also particularly massive sandstone typical Wollsackverwitterung .

In the otherwise largely stone-free environment, the rock group rises a maximum of 47.7 m above the surface of the Wiembecketeich and extends linearly over several hundred meters in length. It begins a bit hidden in the forest with isolated small rocks and extends to the clearly visible 13 relatively free-standing individual rocks. These rock spurs consist of hard, weather-resistant quartz sandstone with small amounts of feldspar and glauconite .

The geological significance of the Externsteine was recognized on May 12, 2006 with the award as a national geotope by the Hanover Academy of Geosciences .

natural reserve

The Externsteine were placed under protection as early as 1926. The Externsteine protected area consisted of several sub-areas designated as natural monuments and was the second protected area in Lippe after the Donoper Teich / Hiddeser Bent area. The aim was to restore the original condition, including the relocation of the road leading between the rocks, the dismantling of modern structures and the removal of the reservoir . The amalgamation of the partial areas into one continuous area according to the Reich Nature Conservation Act of June 26, 1935 was prevented by the SS , which had taken over the management of the Externsteine Foundation. It was not until 1953 that the ten natural monuments were combined to form an Externsteine nature reserve with a size of 140 hectares .

Today there is a 127 hectare Externsteine nature reserve . The rocks themselves are also under protection as a ground monument . The area is important for Europe, which is also documented by the Natura 2000 protection in 2004 within the framework of the European Fauna-Flora-Habitat Directive .

From a nature conservation point of view, not only are the rocks, with one of the largest occurrences of pioneer vegetation on silicate rocks in North Rhine-Westphalia, such as ferns, moss and lichens, particularly valuable, but also the mountain heath with small areas of sloping moors on the neighboring mountain ridges Knickhagen and Bärenstein . Juniper , bog birch and sand birch , blueberries , sedges , rushes , bristle grass , whistle grass , common heather and peat moss grow there . There are large stocks of the three types of orchid spotted orchid (subspecies fox-orchid), mosquito-handelwort and large two-leaf orchid . Also noteworthy are the large populations of the swamp violet and the common adder's tongue .

In addition to the alder and ash forests, which are primarily to be protected in the area, some old oak stocks from former hat forests are important as cultural landscape elements, which were created by the medieval grazing known as "Berghude". Furthermore, larger occurrences of Ilex in the species-rich forest of the NSG are worth mentioning. The (breeding) occurrences of the following protected animal species are particularly relevant for the protection of the area: middle woodpecker ( Dendrocopos medius ), black woodpecker ( Dryocopos martius ), gray woodpecker ( Picus canus ), northern crested newt ( Triturus cristatus ) and hermit ( Osmoderma eremita ). Other species of interest in the NSG are cup-Azurjungfer , hawker , vagrant darter , Azure Damselfly , midwife toad , Noctule , Daubenton's bat , dormouse and water shrew . The eagle owl has been breeding on a smaller side rock since 2006 . The breeding site is cordoned off and guarded on days with special crowds such as Walpurgis Night and the summer solstice. 70 climbing hooks were removed from the Uhubrut rock to prevent illegal climbing.

The former occurrence of the rare liverwort Harpanthus scutatus on the rocks is historically interesting . It was last detected there in 1947. At that time the site was considered to be the last occurrence in North Rhine-Westphalia; Only since the 1990s are a few places in the Egge Mountains known as locations.

The peregrine falcon brooded on the rocks at least in 1885 and 1886. In 1885 there was a successful brood. In 1886 the female of the breeding pair was shot down.

The nature conservation care of the areas is carried out by the forest administration of the Landesverband Lippe , which is also the owner of the rocks, the lower nature conservation authority of the Lippe district and the Lippe biological station . The Lippe Biological Station maps selected species and gives regular guided tours of the area. Measures are being carried out for a nature-friendly visitor management concept. Several damp orchid meadows that were sensitive to footsteps were secured by simple guiding devices. As a biotope maintenance measure, trees were felled to enlarge the heathland areas and to reduce dehydration and shade in a small hillside moor, and to promote weakly competitive moorland species. A herd of sheep and goats from the Lippe Biological Station grazes on heathland.

Description of the rocks

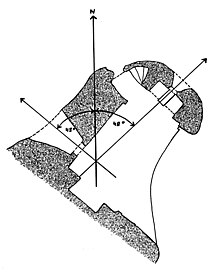

Between the wooded elevations of Bärenstein and Knickenhagen , the Externsteine are located on a line that roughly runs from southeast to northwest. Their individual rocks are counted from northwest to southeast. The two sides of the row of rocks are fundamentally different. On the northeast side of the rocks you can see an abundance of processing tracks. Only a few traces can be found on the south-west facing side. The impression of the mighty cliffs rising from the ground has retained its originality here, while the northeast side has been shaped by human hands in such a way that it gives the impression of a ruin. The northeast side has therefore been called the front and the other the rear. In the following, the description naturally focuses on the front side (NO).

The rock that towers furthest to the northwest, directly in the valley of the Wiembecke, is called Felsen 1. If you continue from there towards the southeast, the striking rock 2 joins, which is conventionally referred to as a tower rock because of its shape . Between the two is a smaller rock, connected to rock 1 close to the ground, so that the large rock 1a is called the small rock 1b. It's called the big rocks 1a even after lying in his cave to cave rock . At Tower Rock (number 2) is followed by another lower that because the stairs to the height of the tower rock overcomes himself up at his sides, as stairs rock is called.

A mighty chasm, through which a road has been running for about 200 years, separates the stair rock from rock 4, on which a mighty chunk lies loosely that threatens to fall to the eye. After this wobbly stone one speaks of the wobbly rock . It is dominated by the adjoining rock 5, which is called the Ruferfelsen after a man's head that is visible at the summit and looking to the southeast . About eight other rocks that have not yet been investigated follow in a south-easterly direction.

Grotto rock

The most important traces on the grotto rock (number 1a) are the caves, the stairs, the summit plateau and the famous rock relief of the Descent from the Cross .

The summit has been leveled like a plateau, so that an area of the same height extends over the top of the grotto rock, which is torn by fissures. About two meters below the summit, on the southwest side, you can see the base of an angular space around the summit.

The rock has had a staircase since 1663 at the latest, probably longer . The staircase begins between the tower rock and the grotto rock and leads to the top of rock 1b and from there to the top of the grotto rock (number 1a). There are traces of older staircases.

Between the grotto rock and rock 1b, a gap has been widened as tall as a man to a corridor that leads to the back of the rock.

Dome grotto

The grotto itself comprises three rooms, which are located along the northeast side and connected to one another. On the south-eastern narrow side of the rock is the entrance to the so-called dome grotto . Next to the entrance is an indistinct figure carved out of the rock with a key, which is often interpreted as Peter. The approximately 4 meter long dome grotto is narrow at the bottom and widens to a dome at the top. Its irregular shape, which only has chisel marks in a few places, is said to have been given by exposure to fire.

Main grotto

A narrow corridor leads to the rectangular main grotto, which extends to the northwest . As all the walls attest, it got its box shape with the help of a hammer and chisel. Its most striking feature is a hemispherical basin about 1.25 meters in diameter, which is sunk into the ground on the southwest wall. Two door openings, one narrow and rectangular, the other wide and arched, give the room light. Next to the rectangular door there is a medieval inscription and a grimace.

Side grotto

The third, also box-shaped room, the side grotto, connects to the north-west end of the main grotto and extends at right angles to the main grotto towards the north-east. Your walls are also processed. The south-east side of the room has two rectangular depressions, one as high as a man, the other a square at heart level.

On the opposite wall, on the edge of a fireplace, a large sign has been carved about an inch deep. Carl Dewitz described this symbol in the side grotto , only half visible at the time, for the first time in 1886 as a "rune symbol". In 1929, the second half of the sign was discovered under a layer of plaster and uncovered with significant participation by Wilhelm Teudt . The symbol was interpreted by Teudt and his successors as a "Binderune" or "Julsymbol" ( Herman Wirth 1933). Others identified it as an early modern depiction of a gallows on the basis of comparable inscriptions on swordsmen ( Kurt Tackenberg 1933, Alois Fuchs 1934, Friedrich Focke 1943) and associated it with the fact that the room was used as a prison for the town of Horn in the early modern period . The latter is the scientifically accepted opinion today.

The outer wall of the side grotto is broken through by a large window, under which the coffin stone lies. From this room a pipe about 4 m long, drilled through the rock, descends at an angle and emerges at the height of the coffin at the head of the same. In the grotto, the opening is next to the window in the floor, but closed with cement.

Sargstein and relief from the Descent from the Cross

The coffin stone at the foot of the grotto rock is worked on all sides. A kind of arcosol tomb with a human-shaped recess for the body to be received is carved into its northwest side . A small platform has been knocked out at the level of the Sargstein, to which stairs lead up from two sides, which have been severely damaged, but the remains of which are clearly visible.

On the outer wall of the artificially created cave, directly in front of the dome grotto, the 5.5 meter high medieval relief from the Descent from the Cross is carved into the external stones . Above the rectangular door you can see a depression, a hollow shape that is reminiscent of the legs, body and wings of a bird.

Tower rock

The tower rock gets its name from the fact that it looks like a square tower when viewed from the southwest. In the height, a space is cut out, the longitudinal axis of which runs approximately towards the northeast, the so-called height chamber . The two narrow sides have each received a niche. The one in the southwest is rectangular and is flanked by two round pillars. The other in the north-east, in which a pedestal with a slim stand - possibly an altar - is lined, is vaulted by a round arch. Above the "stand" there is a round window which, due to its orientation towards the point of rise of the sun at the summer solstice, led to the interpretation that the room could have been used for astronomical observations. For another window, the north-west wall has been broken through two meters deep, exactly in axis with the rocks, roughly aligned with the setting point of the sun at the summer solstice. At the east end of the northwest wall is an expressive male head with an open mouth.

The ceiling of the high chamber was forcibly blown off. On the inaccessible summit, which still partially vaults the room, there is a small elevation, the crown , in which a round depression is carved. At the foot of the tower rock there is a platform on the northeast side, the so-called pulpit . Remnants of seven steps run around the front and one long side. On the top there is an approximately 35 centimeter by 30 centimeter base.

Stair rock

The stair rock (number 3) today offers above all the access to the height chamber of the tower rock, which can be reached from it at a lofty height over an iron bridge covered with wooden planks. Here, too, there are remains of other types of older staircases. At the height of the rock in the southwest there are the remains of a chamber.

Rocking Rock

The most striking thing about rock 4 is the rocking stone on its summit. It rests on three points, but has been lashed with metal straps and the space around its foot is concreted in. The rocking rock (rock 4) is criss-crossed by two vertical fissures that protrude on the front and back. Together with other protruding surfaces, they combine to form recognizable shapes that were only discovered by Fritz Schäfer in the 1950s. There are a large number of traces of processing on both the front and the back, which have suggested the presumption , especially advocated by Walther Matthes since the 1980s , that the naturally existing formations were supplemented by human hands in the direction of a specific expression. On the front you can see the outline of a human figure that seems to be hanging on the rock. On the back of the rock the profile of an animal head with a long neck should be recognizable. A Lippe coat of arms from the 16th and 17th centuries is also embedded in the lower area of the front .

More rocks

Rock 5, the highest of the main group, also has a rock figure at the summit from the northeast, popularly called the Rufer , which, like the other figures according to Matthes, is said to have been created by blasting off flat rocks to create smooth surfaces that in combination with the natural traces of weathering of the surrounding rock produced the desired shapes.

Parallels

The Meteora rocks in Greece form a similar sandstone formation in Europe .

history

The Externsteine were interpreted by Hermann Hamelmann in 1564 as a Germanic sanctuary that had been destroyed by Charlemagne. This interpretation experienced its first climax in the second half of the 19th century with the general interest in prehistory and early history, and then again enjoyed great popularity from the 1920s to 1945. Since then - especially in local history research - these approaches have been taken up again and again, with interpretations ranging from observatories from pre-Christian times to Germanic places of worship . The Externsteine were also known as "Germany's Stonehenge ".

There is little scientific evidence about the Externsteine; instead, there are many myths, legends, and fairy tales floating around. The Holy Grail is believed to be in the stone ensemble; the formations are interpreted as the teeth of a giant. According to the Weser legend of Wackensteinfels, the devil threw the chunk on rock 4 at monks and their chapel, but did not hit them. In esoteric literature, too, there are sometimes fantastic interpretations. Excavations, however, did not provide any clear evidence of cultic use in prehistoric or early historical times, but only document human activities for the early High Middle Ages .

Prehistory and early history

Archaeological finds from the immediate vicinity of the rocks from the Paleolithic (around 10,000 BC) and Mesolithic , in particular flint tips and tees, are certain, but they can only prove that the people of that time visited the stone group - for what reasons The relics do not reveal what the Stone Age people did. On the other hand, there is no reliable evidence from finds for human use in the Neolithic , Bronze and Iron Ages .

In the immediate vicinity of the stones there are several ravines - including the Große Egge ravine - which are often incorrectly referred to as the remains of " Roman paths ". The origins of these relics of historical traffic relations are certainly not with the Romans . Whether they originated in prehistoric times or not until the Middle Ages cannot currently be decided.

More recent thermoluminescence dating from the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences showed that the oldest sampled fireplace in the dome grotto was used with a high degree of probability at a point in time that cannot be precisely determined between the middle of the 6th and the beginning of the 10th century (735 ± 180 AD). . Another fireplace in the same grotto was used in the 9th to 11th centuries (934 ± 94 AD). One sample from the secondary grotto is younger than 1025 ± 100 AD and two further traces of fire in the main and secondary grotto date from the late Middle Ages (1325 ± 50 AD and 1425 ± 63 AD). Older uses of these fireplaces can neither be excluded with this investigation method nor are they necessarily assumed. This means that the use of the caves in prehistoric times cannot be ruled out by these investigations, but there is still no reliable evidence for this.

Some astronomers, on the other hand, have pointed to a possible pre-Christian use of the tower rock and other parts of the Externsteine for the purposes of sky observation .

middle Ages

A modern evaluation of the archaeological finds, in particular the ceramics and metal goods, resulted in a dating of the objects from the late 10th to the 19th century. The at least temporary presence of people at the rock group derived from this fits in with an Abdinghof certificate, according to which the Externsteine are said to have been bought by the Paderborn monastery in 1093 .

The monks of the surrounding monasteries, perhaps also from Paderborn, were most likely the originators of architectural and design work on the Externsteine and in their surroundings. The objects that cannot be dated from an art-historical point of view, such as B. the rock grave ( Arkosol ) and the upper chapel (Felsen 2), which in art historical research are often interpreted as replicas of the Jerusalem Passion Sites based on the Abdinghof property claims, are perhaps also medieval and commissioned by monks. The higher chapel with altar is associated with the height of Golgotha. The caves in the sandstone cliffs were used as a hermitage . In the main grotto, sometimes also called the lower chapel , there is a dedicatory inscription with the year 1115. Its authenticity is also not undisputed.

The well-known relief from the Descent from the Cross , carved into the grotto stone , is dated to the time between 1130 and 1160 by art historical research after the due re-evaluation in the 1950s, in which Otto Schmitt, Fritz Saxl and Otto Gaul participated. There are also divergent dates, for example to the Carolingian period, in which, according to Walther Matthes, the Externsteine are said to have been the unknown location of the Hethis Monastery , the predecessor of Corvey , between the years 815 and 822 . Art historians assume that the relief - which is recognized as one of the largest in Europe in the open air - is a holy grave for the believers who could not make the pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

That the relief was only made by Lucas Cranach the Elder in the 16th century . Ä. was created is unlikely, given the way it works and the style. It is considered to be the oldest stonemason sculpture north of the Alps carved from solid rock. For the often alleged high medieval use of the rocks as a place of pilgrimage, both medieval sources and clear indications in the finds are missing.

17th to 20th century

Since 1665 there was a timber-framed forest house in the immediate vicinity of the stones, which also contained a pub.

In the 17th century , a fortress-like pleasure palace was built below the Externsteine by the Lippe sovereign, Count Hermann Adolf zu Lippe-Detmold , who became the owner of the square after the Reformation , which probably also served to control road traffic, but otherwise remained almost unused after a short time and fell into disrepair. It was demolished around 1810 on the instructions of Princess Pauline of Lippe , and the area around the Externsteine was restored to its original state.

In 1836, for romantic and aesthetic reasons, the Wiembecke brook flowing below the rock group was dammed up to become the Wiembecketeich . This artificial pond was drained during the Nazi era for excavation purposes and as part of the design of the area, but it was rebuilt after 1945.

In 1855 the forester and tenant of the pub bought the forest and inn. His son had a neo-Gothic hotel built next to it in 1867, which was designed in large dimensions by the architect Friedrich Gösling . The Hotel Externsteine with restaurant determined the appearance of the Externsteine for the next 100 years or so.

In 1881 and 1888 the first archaeological excavation campaigns took place at the Externsteine under rather modest conditions. In retrospect, it can be assumed that more was destroyed than discovered back then. In 1932 an archaeological exploratory excavation was carried out by a monument conservationist on behalf of the then Free State of Lippe .

To ensure traffic safety, the rocking stone , which according to old stories should fall on enemies of the place, was fastened with iron hooks.

time of the nationalsocialism

The centuries-old idea of the Externsteine as a Germanic place of worship was taken up by the Völkisch movement . The core thesis of this otherwise inconsistent movement was the assumption of a Germanic or Nordic high culture before the ancient high cultures of the Mediterranean, the so-called Germanic myth . Völkisch lay researchers believed to have found evidence of this in the stone setting of the megalithic culture as well as in the art of the Migration Period and the Vikings. This is also the case with Wilhelm Teudt , who believed to have discovered the site of what was supposed to be the main Saxon shrine of Irminsul in the mid-1920s . The Irminsul was valid in ethnic and neo-pagan circles as a symbol of the last resistance of the old Germanic religion before it was destroyed by Charlemagne in the course of Christianization .

Teudt, who was a member of numerous ethnic organizations and from May 1, 1933 a member of the NSDAP , suggested to the National Socialists after they came to power that the Externsteine be redesigned into a “holy grove” in memory of their ancestors. Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler, with his fondness for everything supposedly Germanic, took up the idea and founded the Externstein Foundation in 1933; he himself was its chairman.

In 1934 and 1935, extensive archaeological excavations were carried out under the direction of geologist and active NSDAP member Julius Andree with the help of the Reich Labor Service , the documentation of which has been incomplete since 1945. The declared aim of the excavations was to find evidence of a pre-Christian Germanic cult site on the stones. These excavations are generally regarded by today's scientific archeology as "initiated archaeological purpose research ". Some of the ceramic and metal finds from the two excavations are now kept in the Lippisches Landesmuseum Detmold . During the excavations, Andree discovered and examined a rampart northeast of the stones, the Immenburg on the parcel of the same name.

Basically and predominantly two different organizations dealt with the "Externsteinforschung" during the time of National Socialism: the SS- Forschungsgemeinschaft Deutsches Ahnenerbe and the so-called Amt Rosenberg .

Since 1945

In the years from 1964 to 1966, the area surrounding the Externsteine was upgraded. A large parking lot and a restaurant were newly built outside of the direct line of sight to the stones. The Hotel Externsteine was demolished in 1867 for this purpose. Since then, the Externsteine have been looking quieter despite the large number of visitors.

Since the end of the 1990s, the council of the town of Horn-Bad Meinberg has been considering expanding the square at the Externsteine to an event location as part of town marketing (from gentle marketing to large esoteric events to the construction of musicals ). These plans have been heavily criticized, especially by nature conservationists and monument conservationists, and have not yet been implemented.

Transport development and tourism

In 1813, the old long-distance path running through the rocks - today's hiking trail - was paved and expanded to the road. When trunk road numbering was introduced in 1932, the road became part of trunk road No. 1 (Aachen-Königsberg); it was renamed Reichsstrasse 1 in 1934 and relocated to the southeast in 1936 (since 1949 Bundesstrasse 1 ). In 1940 the former Reichsstraße was closed to public motor vehicle traffic and the area was declared a recreation area.

From 1912 to 1935 wrong on the highway a Regional tramway of PESAG of Paderborn about Horn to Detmold , which had a stop at the rocks. Until 1941, on summer Sundays and public holidays, trams still ran on a branch line to Horn-Externsteine. In 1953, the Externstein section of the tram route, which had previously only been used irregularly and for tourist purposes, was given up. To this day, indentations and metal remains of the systems can be seen on the rocks.

Between half a million and a million people visit the Externsteine every year.

Some of the Externsteine can be climbed. The Höhenkammer can be visited between April 1st and November 3rd. Away from the paths, however, climbing and stepping on the rock heads is strictly prohibited to protect the rare vegetation and is sometimes clearly signposted.

The peaks of the rocks located directly on the pond can be reached via stairs that are laboriously carved into the rock and a bridge high up in the rock. From there there is a good view in north to east direction, which, if the weather is suitable, extends to the distant Köterberg . In other directions the view is largely blocked because of the extensive and higher forest areas. During the day an entrance fee has to be paid for the ascent to both rocks; Outside the opening times, however, one of these rocks is free and fully accessible.

Hikers can reach the Externsteine from the north via the Hermannsweg and from the south via the Eggeweg , which is part of the European long-distance hiking trail E1 . A total of almost 10 km long hiking trails open up the area.

mascot

The mascot of the Externsteine is "Steini". Similar to z. B. Jan Cux for the seaside resort of Cuxhaven, Steini serves to promote tourism. Steini and the Externsteine is also a so-called “Children's Edition” of the popular Externsteine App . The contents are “prepared and produced in a child-friendly manner” according to self-presentation. With the help of the mascot Steini, children should explore and discover the nature trails on the Externsteine. Steini is supposed to represent the distinctive and highest "rock 2", which is conventionally referred to as a tower rock because of its shape .

Place of worship for esoteric and political groups

Various groups, esoteric in the broadest sense, regard the Externsteine as a “ place of power ” with extraordinary geomantic and spiritual properties. The area around the Externsteine is also often included in these theories, for example the Bärenstein with the local quarry and the so-called fairy meadow. Especially in the neo-pagan scene, the dates of the first cultic use are doubted as too late, and only the takeover of an older cult site by the Christians is being considered.

Already in 1953 the Indian by choice Savitri Devi , an admirer of Hitler , spent a night in a cave of the Externsteine, which she regarded as an old Germanic sanctuary. She says she experienced death and rebirth there and called the names of Vedic gods and Hitler's from a rock at sunrise .

On May 1st and especially on Walpurgis Night and Summer Solstice , festival-like celebrations take place at the Externsteinen as a place of worship, with the largest organized meetings of many groups and individuals from the esoteric spectrum in Germany. Since 2010, tents, alcohol and campfires have been banned on Walpurgis Night and on the summer solstice. However, the alcohol ban was not enforced on Walpurgis Night.

The Externsteine are also a symbol for groups such as the Free Comradeships . Around 2004, the Young Conservatives buried objects such as the German flag , linden leaves, genetically pure grains and specimens of Junge Freiheit under the catchphrase “Mourning Germany” .

Others

The German Federal Post Office brought in 1989 a 350-pfennig stamp out the Externsteinen as a motive.

literature

Short guide

- Johannes Mundhenk: Externsteine. 4th edition. Wagener, Lemgo 1984 (= Lippe sights , booklet 2), ISBN 3-921428-08-4 .

- Elke Treude, Michael cell: The Externsteine near Horn. (= Lippe cultural landscapes , issue 18). Lippischer Heimatbund, Detmold 2011, ISBN 978-3-941726-18-5 , ISSN 1863-0529 .

Archeology and history

- Walther Matthes : Corvey and the Externsteine. Fate of a pre-Christian shrine in Carolingian times. Urachhaus publishing house, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-87838-369-X .

- Johannes Mundhenk : Research on the Externsteinen. Wagener, Lemgo 1980–1983 (= Lippische Studien, Volumes 5–8), ISBN 9783921428313

- Friedrich Hohenschwert , Heinrich Beck , Jürgen Udolph , Wolfhard Schlosser : Externsteine. In: Heinrich Beck u. a. (Ed.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . 2nd ext. Edition Volume 8, de Gruyter , Berlin / New York 1994, ISBN 3-11-013188-9 , pp. 37-49.

- Robert Jähne, Roland Linde, Clemens Woda: Light into the darkness of the past. The luminescence dating on the external stones. Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 2007 (= series of publications of the protection community Externsteine, 1), ISBN 3-89534-691-8 .

- Burkard Steinrücke, New measurement and new analysis of the presumed astronomical bearings on the Externsteine (PDF), 2013

Research and reception history

- Erich Kittel : The Externsteine as a playground for swarming spirits and in the judgment of science. In: Lippische Mitteilungen aus Geschichte und Landeskunde Volume 33, 1964, pp. 5-68. Again as an unchanged reprint, NHV , Detmold 1965. ( digitized version )

- Erich Kittel: The Externsteine: A critical report on their research and interpretation along with a guide through the facilities. 7th edition. Detmold 1984 (= special publications of the Natural Science and Historical Association for the Land of Lippe, 18), ISBN 3-924481-01-6 .

- Uta Halle : "The Externsteine are Germanic until further notice!" Prehistoric archeology in the Third Reich . Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, Bielefeld 2002 (= special publications of the Natural Science and Historical Association for the State of Lippe, 68), ISBN 3-89534-446-X (see also the review of H-Soz-u-Kult by Gregor Hufenreuter )

- Uta Halle: The Externsteine - a symbol of Germanophile interpretation. In: Achim Leube, Morton Hegewisch (ed.): Prehistory and National Socialism. Central and Eastern European Prehistory and Early History Research in the years 1933–1945. Heidelberg 2002 (= Studies on the History of Science and University, 2), ISBN 3-935025-08-4 , pp. 235-253.

- Uta Halle: "Driftings like in the Nazi era". Continuities of the Externstein myth after 1945. In: Uwe Puschner, Georg Ulrich Großmann (Ed.): Völkisch und national. On the topicality of old thought patterns in the 21st century. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2009 (= scientific supplements to the Anzeiger des Germanisches Nationalmuseums, 29), ISBN 3-534-20040-3 , pp. 195-213.

- Larissa Eikermann, Stefanie Haupt, Roland Linde and Michael Cell (eds.): The Externsteine between scientific research and ethnic interpretation . Aschendorf, Münster 2018, ISBN 978-3-402-15122-8 .

Web links

- The Externsteine. A monument as an object of scientific research and a projection surface for folk ideas

- "Externsteine" nature reserve in the specialist information system of the State Office for Nature, Environment and Consumer Protection in North Rhine-Westphalia

- Website of the municipal association and owner of Felsen LVL , landesverband-lippe.de

- Externsteine Flyer from the Landesverband-Lippe, published 2014 (pdf)

- Historical photos

- Pictures of the natural monument in the picture archive of the LWL media center for Westphalia

- Pictures of the natural monument in the picture archive at Lipperland.de

- 360 ° panoramic image of the Externsteinen in the Westphalian Cultural Atlas (requires Flash player )

- Pictorial representation of mascot Steini in high resolution here

Individual evidence

- ^ Monumenta Paderbornensia. 2nd edition, Amsterdam 1672, p. 71, illustration p. 72.

- ↑ "A quarter of an hour away is the old monument, called Rupes Picarum or the Externstein". In: Newly multiplied historical and geographical general lexicon. 2nd part. Basel 1726, p. 835.

- ↑ Jürgen Udolph, Heinrich Beck: Externsteine, § 7. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 8, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1994, ISBN 3-11-013188-9 , pp. 46-48.

- ↑ Ernst Casimir Wasserbach (ed.): Hermanni Hamelmanni opera genealogico-historica de Westphalia et Saxonia inferiori: in quibus non solum res gestae seculi XVI & anteriorum temporum ... ehibentur Sed & de totius Westphaliae provinciis, urbibus ... historia traditur. Meyersche Hofbuchhandlung, Lemgo 1711, p. 79 .

- ↑ Birgit Meineke : The place names of the Lippe district. (= Westphalian Place Name Book (WOB), Volume 2). Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 2010, ISBN 978-3-89534-842-6 , p. 245.

- ↑ a b Jörg Mutterlose: The Lower Cretaceous outcrops of the Osning sandstone (NW Germany) - your fauna and lithofacies. - Geology and paleontology in Westphalia. 36 (1995), p. 52. dig

- ^ Alfred Hendricks, Alfred Speetzen: The Osning sandstone in the Teutoburg Forest and in the Egge Mountains (NW Germany) - a marine coastal sediment from the Lower Cretaceous Period. Münster 1983 (= treatises from the Westphalian Provincial Museum for Natural History, 45).

- ↑ a b Jörg Mutterlose: The Lower Cretaceous outcrops of the Osning sandstone (NW Germany) - your fauna and lithofacies. - Geology and paleontology in Westphalia. 36 (1995), p. 13. dig

- ^ Fritz Runge: The nature reserves of Westphalia and the former administrative district of Osnabrück. 3. Edition. Aschendorff, Münster 1978, ISBN 3-402-04382-3 , pp. 143-144.

- ^ Geological State Office of North Rhine-Westphalia : Eggegebirge Nature Park - southern Teutoburg Forest (Geological hiking map 1: 50000). 2nd ed. Bonn, 1986, Explanation No. 2 Die Externsteine .

- ↑ Academy of Geosciences and Geotechnologies eV Hannover: List of the National Geotopes of Germany awarded on May 12, 2006 in Hannover (PDF; 24 kB)

- ^ Kurt Rohlfs: History of the nature reserve designation . In: Nature reserves in Lippe. Journey of discovery through a natural and cultural landscape . Verlag Jörg Mitzkat, Holzminden 2010, ISBN 978-3-940751-22-5 , p. 21-22 .

- ↑ a b c "Externsteine" nature reserve in the specialist information system of the State Office for Nature, Environment and Consumer Protection in North Rhine-Westphalia , accessed on February 24, 2017.

- ↑ a b c d FFH protected area DE-4119-301 "Externsteine" (Natura 2000)

- ↑ Helmut Brinkmann: The flora of the Externsteine nature reserve. In: Heimatland Lippe 75 (1982), ISSN 0017-9787 , pp. 359-364.

- ↑ Lippischer Heimatbund (Ed.): Nature reserves in Lippe. Lippischer Heimatbund, Detmold 1986.

- ↑ Martin Lindner, Gisbert Lütke, Ralf Jakob, Doris Siehoff: The conflict between climbing and nature conservation in North Rhine-Westphalia (Part 2). Annual report 2009 of the working group Peregrine Falcon Protection of NABU NRW, 18-22

- ↑ Carsten Schmidt, Jochen Heinrichs u. a .: Red list of endangered mosses (Anthocerophyta et Bryophyta) in North Rhine-Westphalia. 2nd version. In: State Institute for Ecology, Land Management and Forests (Hrsg.): Red list of endangered plants and animals in North Rhine-Westphalia. 3rd version, LÖBF, Recklinghausen 1999 (= LÖBF series of publications, 17), ISBN 3-89174-030-1 , pp. 173-224 ( online version, PDF ( Memento from April 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ Martin Lindner: A historical peregrine falcon preparation from 1886 from the Externsteinen . In: Working group peregrine falcon protection of NABU NRW: 25 years working group peregrine falcon protection AGW North Rhine-Westphalia . NABU-NRW, Düsseldorf, pp. 54-55.

- ↑ Biological Station Lippe NSG Externsteine ( Memento from November 25, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Johannes Mundhenk: Research on the history of the Externsteine. Volume 1: Architectural-archaeological inventory , Lemgo 1980 (= Lippische Studien, 5), pp. XIX-XXVII

- ↑ Johannes Mundhenk: Research on the history of the Externsteine ... Volume 1, through

- ↑ Rolf Speckner , Christian Stamm: The secret of the Externsteine. Images of a mystery site. Urachhaus, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-8251-7402-6 , pp. 120-123.

- ↑ Ulrich Niedhorn: Prehistoric plants at the Externstein Rock. Haag and Herchen, Frankfurt am Main 1993 (= Isernhägen studies on early sculpture, 5), ISBN 3-86137-094-8 , pp. 77-83.

- ↑ Ulrich Niedhorn: Prehistoric plants at the Externstein Rock. Haag and Herchen, Frankfurt am Main 1993 (= Isernhägen studies on early sculpture, 5), p. 66f., Illustration in original size p. 67–69.

- ^ Carl Dewitz: The Externsteine in the Teutoburger Walde. Breslau 1886. ( Online version of the LLB Detmold )

- ↑ Johannes Mundhenk: Research on the Externsteinen ... Volume 1, p. 54.

- ^ Wilhelm Teudt: The Externsteine as a Germanic sanctuary. Eugen Diederichs Verlag, Jena 1934, p. 10.

- ↑ Herman Wirth: The rock grave at the Externsteinen. In: Germanien 1933, Issue 1, pp. 11–15, p. 11.

- ↑ Kurt Tackenberg: The bas-relief and the lower chapel of the Externsteine. In: Niedersachsen 38 (1933), pp. 299-304, pp. 303 f.

- ↑ Alois Fuchs: In the dispute about the Externsteine. Verlag der Bonifacius-Druckerei, Paderborn 1934, p. 94.

- ^ Friedrich Focke: Contributions to the history of the Externsteine. Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart and Berlin 1943, pp. 73-76.

- ↑ Alexandra Pesch: One more drop on the hot stones ... About the runic inscription discovered in 1992 on the external stones. In: Wilhelm Heizman / Astrid van Nahl (eds.): Runica Germanica Mediaevalia , de Gruyter, Berlin a. a. 2003 (= Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, supplementary volume 37), pp. 567-580, here p. 568.

- ↑ Friedrich Hohenschwert a. a .: Externsteine. In: Reallexicon for Germanic antiquity. 2nd ext. Ed., Vol. 8, 1994, pp. 37-49, pp. 40.

- ↑ Johannes Mundhenk: Research on the history of the Externsteine ... Volume I, p. 77ff.

- ↑ a b c Walther Matthes: Corvey and the Externsteine. Fate of a pre-Christian shrine in Carolingian times. Urachhaus, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-87838-369-X , pp. 199ff. ("The great figures of rock 4")

- ↑ Süddeutsche Zeitung: Fairytale rocks. Retrieved March 21, 2020 .

- ↑ Sage: The rocking stone on the Externsteine. Retrieved March 21, 2020 .

- ↑ Robin Jähne, Roland Linde, Clemens Woda: Light in the darkness of the past. The luminescence dating on the external stones. Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-89534-691-0 ; Günther A. Wagner: Introduction to Archaeometry . Springer-Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-540-71936-6 , pp. 24-26.

- ↑ Rolf Müller: The sky above man in the Stone Age. Astronomy and mathematics in the buildings of megalithic cultures , Springer-Verlag, Berlin a. a. 1970 (= Understandable Science, 106), ISBN 3-540-05032-9 , pp. 88-95; Wolfhard Schlosser : Astronomical abnormalities on the external stones. In: Ralf Koneckis, Thomas Reineke (ed.): Secret Externstein. Results of new research. a selection of the conference contributions from the 1st and 2nd Horner symposium from September 21 to 24, 1989 and from September 20 to 22, 1991. Topp + Möller, Dortmund 1995, ISBN 3-9803614-1-1 , p. 81– 90; Wolfhard Schlosser, Jan Cierny: Stars and stones: a practical astronomy of the past. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1996, ISBN 3-534-11637-2 , pp. 93-95.

- ↑ Andreas Fasel: Suspicious Chamber . October 6, 2013 ( welt.de [accessed November 30, 2019]).

- ↑ The authenticity of the document has been questioned and disputed several times. It is no longer available because the archive 1163 burned down. There may have been a document note afterwards, but this too was lost in the 17th or 18th century. Since then, there is only one copy of the document from that time. See Johannes Mundhenk: Research on the history of the Externsteine ... Volume 3, p. 79ff.

- ^ Anke Kappler, Anke Naujokat: Jerusalemskirchen: Medieval small architectures based on the model of the Holy Sepulcher . Geymüller Verlag für Architektur, 2011, ISBN 978-3-943164-01-5 .

- ↑ Ulrich Niedhorn: The 'Weihinschrift' in the lower grotto of the Externsteine. In: Lippische Mitteilungen. 55: 9-44 (1986).

- ↑ Otto Schmitt: On the dating of the Externstein relief. In: Oswald Goetz (Ed.): Articles for Georg Swarzenski on January 11, 1951. Mann, Berlin 1951, pp. 26–38; Fritz Saxl: English Sculptures of the 12th Century. ed. by Hanns Swarzenski. Faber & Faber, London 1954; Otto Gaul: New research on the problem of the Externsteine. In: Westphalia. 32: 141-164 (1955).

- ↑ Walther Matthes: On the origin of the relief from the Descent from the Cross on the Externsteinen. In: Ernst Benz (Ed.): The limit of the feasible world. Festschrift of the Klopstock Foundation on the occasion of its 20th anniversary. Brill, Leiden 1975, ISBN 90-04-04343-8 , pp. 133-190; Walther Matthes: Corvey and the Externsteine. Fate of a pre-Christian shrine in Carolingian times. Urachhaus, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-87838-369-X ; Walther Matthes, Rolf Speckner: The relief on the external stones. A Carolingian work of art and its spiritual background. Edition Tertium, Ostfildern vor Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-930717-32-8 .

- ↑ Uta Halle: "The Externsteine are Germanic until further notice!" Prehistoric archeology in the Third Reich. Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, Bielefeld 2002 (= special publications of the Natural Science and Historical Association for the Land Lippe, 68), p. 44, p. 342.

- ↑ a b c externsteine-teutoburgerwald.de: Hotel Ulrich

- ↑ externstein.de - “Against the marketing of the Externsteine” (documentation of an SPD application in the Horn-Bad Meinberg city council in 2002 and some reactions).

- ↑ Hp Paderborn: 52 years ago today the last tram ran in Paderborn published September 2015

- ↑ a b Tram Schlangen – Horn from 1912 to 1953. ( Memento from May 26, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Eisenbahnfreunde Lippe eV, Issue No. 10, October 2002

- ↑ Landesverband Lippe, in: http://www.externsteine-info.de , as of September 3, 2014

- ↑ "Steini - the mascot of the Externsteine - accompanies you on your way and gives you great tips!" The quote can be read here

- ↑ "Together with the mascot" Steini "you can discover the world of the Externsteine at seven game and puzzle stations" - quote to read here

- ^ "Steini" on the website of the information center of the Externsteine

- ↑ Notes on the app on appadvice.com

- ↑ Cordula Gröne (2012): Trees on the Externsteinen make room for eagle owls and falcons, work should secure the stock , Lippische Landes-Zeitung, as of September 6, 2014

- ↑ Andreas Fasel (2008): Walpurgis Night at the Externsteinen , Welt am Sonntag, May 4, 2008, as of September 6, 2014

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke : In the Shadow of the Black Sun. Aryan Cults, Esoteric National Socialism and the Politics of Demarcation. Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-86539-185-8 , pp. 206f. (Original Black Sun, 2002.)

- ↑ No more "coma-drinking" on Externsteinen. In: Mindener Tageblatt. April 10, 2010.

- ↑ Uta Halle: Drifts like in the Nazi era - continuities of the Externstein myth after 1945. In: Uwe Puschner , G. Ulrich Großmann (ed.): Völkisch und national. On the topicality of old thought patterns in the 21st century. Knowledge Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-534-20040-5 , pp. 208f.

Coordinates: 51 ° 52 ′ 8 ″ N , 8 ° 55 ′ 3 ″ E