Cult of Reason

The cult of reason ( French: Culte de la Raison ) belonged, like other revolutionary cults, to an ensemble of civil religious festivals and beliefs during the French Revolution , which was to take the place of Christianity and especially Catholicism in the socio-political center. The de-Christianization was connected in a special way with the cult of the Supreme Being , which was different from the cult of reason and based on deistic convictions. Supported by social revolutionary groups, the cult took on a semi-official character between autumn 1793 and spring 1794.

Belief content

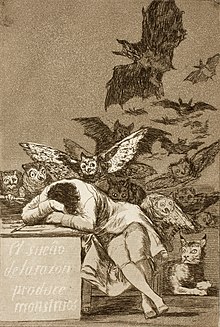

The cult of reason was rooted in the skepticism of the Enlightenment towards traditional creeds. The advocacy of reasoned thinking and acting motivated a worldview that, if it did not completely deny the existence of God, saw God as the immanent principle of the omnipresent order established and functioning according to natural laws. Through scientific examination, superstition and everything illogical should be eliminated from religion and a rationalistic piety created. Voltaire , the most prominent church critic, took the deist view that God, whom he compared to a clockmaker , had created the natural order but is now no longer intervening, and coined the words «écrasez l'infâme» (“Smash the abominable [Church ] ").

After the outbreak of the revolution, the anti-clerical Jacobins under the leadership of Jacques-René Hébert and Pierre Gaspard Chaumette pursued religious policy as a consistent action against the established church, which they saw as the organizational backbone of the internal and external counterrevolution . Their anti-clerical thrust took on largely anti-religious traits, and they were among the main initiators of de-Christianization. Atheist beliefs were widespread among the Hébertists and were in opposition to Maximilien de Robespierre's cult of the supreme being . The cult of reason propagated by Hébert and Chaumette was also one of the deist forms of belief that saw everything subject to the rules of a “clockwork universe”; the ritually revered reason possessed the numinous character of a mere functional deity , God the status of a demiurge . The cult of reason thus clearly positioned itself as an antithesis to the theism of Catholicism.

Spread and suppression of the cult

Militant appearances against the church had already taken place with the “ September murders ” of 1792 and in the summer of 1793, and from autumn onwards, de-Christianization turned into a mass movement primarily supported by the petty bourgeoisie ; this first found its supporters in the provincial cities south of Paris and in Lyon and often expressed itself in carnival-like processions with church utensils , desecration of churches, iconoclasms or ceremonies for revolutionary martyrs organized by ambassadors from the National Convention . The movement quickly spread to the center and in October the commune of Paris banned all public religious ceremonies. The de-Christianization was associated with a “transfer of the sacred”, which was most impressively expressed in the popular veneration of the revolutionary martyrs , especially Jean-Paul Marat . The cult of martyrs had to worry all those who represented atheist or deist views, and the Hébertists sought to meet the need for a “substitute faith” with the creation of the cult of reason. At the instigation of Chaumette, the first festival in honor of reason (originally planned as a festival in honor of freedom in the Palais-Royal ) was held on November 10, 1793 in the Notre-Dame Cathedral , which has been rededicated in a "Temple of Reason and Freedom" has been. On November 23, 1793, the National Convention passed a law that withdrew all places of worship in Paris from cult and made them further temples of reason, and that the festival of reason should be celebrated on every décadi (tenth day) of the new revolutionary calendar . These measures spread through state and parastatal organs from Paris over large parts of France.

The cult of reason met with broad resistance from the population from the start. Even Danton spoke of "anti-religious masquerades". The bulk of the population could not follow the visionary utopian attempt of an intellectual elite to transform abstract concepts into purely rational beliefs. Robespierre was aware of this and on November 21, 1793, in the Jacobin Club , he spoke out in favor of freedom of worship. Apart from his own beliefs, which could not be reconciled with the strongly atheistic cult of reason, he recognized in the abolition of church services a political error that ignored the emotional needs of the people and the number of enemies of the republic at home and abroad increased. On December 6, 1793, the convention warned the freedom to practice religion, which it promised to uphold. Robespierre warned again of the dangers of de-Christianization, and even the Paris commune followed this line. However, nothing changed in the measures taken, and the churches remained civil religious temples. The status quo did not change until the end of March 1794; after the persecution and execution of the Hébertists, the cult of reason was also suppressed.

Aftermath

Elements of the cult of reason were preserved in the subsequent short-lived cult of the highest being as well as under the changeable repressive religious policy until Napoleon's compromise with the Catholic Church in the Concordat of 1801 . Under the cult of the highest being, the décadis should have continued to be dedicated to the celebration of the state, albeit no longer to reason, but to similar values such as truth or justice. The official reintroduction of the culte décadaire at the end of October 1795 proved to be ineffective; it only lasted until 1800. The official festivals lost their popular character and were more of a republican exercise. Several attempts by the creation of other civil religious cults were mere suggestions, only the committed deism theophilanthropy gained from 1796 to its ban in 1801/1803 some distribution. The idea of a rational religion was propagated not least by the early socialist Henri de Saint-Simon , who spoke of a Newtonian religion in 1802 (Isaac Newton with his fundamental insights into gravity, light and electricity always played a special role as a symbolic figure for rationalist worldviews of this time) and with his work Nouveau Christianisme (German New Christianity ) of 1825 gave a name to his social philosophy based on reason.

literature

- François-Alphonse Aulard : Le culte de la raison et le culte de l'Être Suprême (1793-1794): essai historique. Paris 1892 ( digitized version )

- François-Alphonse Aulard: Political History of the French Revolution - Origin and Development of Democracy and Republic 1789-1804 . Two volumes, introduced by Hedwig Hintze . Duncker & Humblot, Munich 1924 (original title: Histoire politique de la Révolution française, origines et développement, de la démocratie et de la république, 1789–1804 , four volumes, 1910, translated by Friedrich von Oppeln-Bronikowski), DNB 560329229 .

Web links

- Sabine Büttner: The French Revolution - an online introduction: Areas of Effect, IV. Church and Religion (19-03-2006)

- Doris Gretzel: French Revolution and Religion - From Persecution to De- Christianization (19-03-2006)

- Georges Goyau: French Revolution . In: The Catholic Encyclopedia 1912 (19-03-2006, English)