Orchomenos dome tomb

Coordinates: 38 ° 29 ′ 35.6 ″ N , 22 ° 58 ′ 28 ″ E

The dome grave of Orchomenos ( Modern Greek Θολωτός τάφος του Ορχομενού ), known as the "treasure house of Minyas " ( Modern Greek Θησαυρός του Μινύα ), located in the Greek countryside Viotia , in the western part of the town of Orchomenos , southwest of the ancient theater. This is an underground tholos building that was built during the late Helladic period in the 13th century BC. Was built. It was excavated by Heinrich Schliemann .

Pausania's lore

Pausanias , who traveled to Greece in the middle of the 2nd century AD, had apparently found the grave intact, because he reports from his visit to Orchomenos: “The treasure house of Minyas, a miracle building that is inferior to any other in Greece itself or elsewhere , is constructed as follows: it is made of stone, round in shape and not very pointed at the top; the top stone should give the whole building the context. ”. Following the description, Pausanias mentioned the tombs of the mythical King Minyas and of Hesiod. In part, this passage was interpreted in such a way that the tombs were located within the treasury, which is why the Tholos tomb is also called the tomb of Hesiod ( modern Greek Τάφος του Ησίοδου ). Others suspected that these graves were only in the area.

exploration

It served as a landmark for European travelers who traveled to Greece at the beginning of the 19th century. These travelers included Edward Dodwell , William Martin Leake, and Lord Elgin . The latter commissioned artists to dig for treasure in the grave. However, since large blocks of stone had to be retrieved for this purpose, this project was quickly abandoned. In 1862 the marble blocks of the Dromos were used to build a new church. Before this was completely removed, the responsible ministry prohibited further destruction of the Tholos tomb.

In the years 1880, 1881 and 1886 Heinrich Schliemann carried out systematic excavations and almost completely uncovered the grave. In 1907 Heinrich Bulle and Wilhelm Dörpfeld examined the grave holos again. In 1914, the walls of the building were restored under the direction of the Greek archaeologist Anastasios Orlandos .

description

The Treasury of Minyas is the second largest Mycenaean domed tomb and is only slightly smaller than the Treasury of Atreus in Mycenae . However, the equipment of the tomb was probably richer. It was built from local marble quarried in the Livadia area .

The entrance to the tomb was reached via the so-called Dromos , an access path flanked on both sides by a wall made of carefully worked ashlars. The walls rose in the direction of the grave until they reached about the height of the gate. The access path was 5.11 m wide and was paved with marble slabs. As the dromos was almost completely removed, its exact length is unknown. It is believed that it was about 40 m long.

The gate is 5.51 m high and 2.71 m wide at the bottom and tapers to 2.47 m at the top. It is unknown whether the facade was similar to that of the Atreus Treasury, as nothing has been preserved from the facade. The doorway ( stomion ) had a length of 5.29 m and was probably covered with two capstones of which only the inner one remained. It has a length of 5 m, a width of 2.22 m and a thickness of 0.965 m and weighs about 25 t. The curve of the dome is incorporated on the inside of the capstone. There was very likely a relief triangle above the capstones. Here, the next stone layer was laid over the capstones only over the side walls. No stones were built directly above the entrance. With each additional stone layer, the stones were moved closer together so that a triangle remained free above the door lintel. In this way, the capstones were relieved and the weight of the stone mass above the entrance was borne by the side walls. The triangle was walled up inside and out or covered with stone slabs so that it was not visible. The door threshold with drill holes for a double-leaf door dates from Roman times.

The grave dome is not completely round. It has a diameter of 13.84 m in the north-south direction and in the west-east direction of 14.05 m. The dome collapsed today and only the lower stone layers have been preserved. The original height is estimated to be around 14 m. The dome was built from rectangular, well-worked stones as a false vault in the shape of a beehive. From the fifth row of stones, each stone has a hole. Some of the bronze nails to which bronze rosettes were attached are still stuck in these holes. The stones of the eighth stone layer have about 5 cm large and 1 cm deep indentations with a hole in the middle. Here, too, there were apparently bronze decorative panels. The floor of the round room is made of smoothed rock. In the rear part there is an installation with a Π-shaped floor plan from Roman times. This probably belongs to a temple that was built in the chamber in Hellenistic times . It is believed that there was a hero cult here in which Minyas or Hesiod were worshiped. According to an inscription, Hera Teleia was also worshiped here. In Roman times statues of emperors were erected. Schliemann found a 3.50 m thick layer of ash in the Tholos. Paul W. Wallace therefore assumed that the grave was used as a kiln for bricks in Byzantine times.

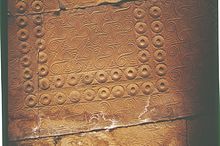

In the northeast of the Tholos there is a door through which you can get into a side room, the so-called Thalamos . The passage is surrounded by three rows of holes for fixing bronze ornaments. It has a height of 1.92 m and its width tapers from 1.19 m up to 1.12 m. The room could be closed with a single-leaf door. The 3.76 m deep and 2.74 m wide adjoining room was dug into the rock from above. The walls were clad with 2.40 m high stone slabs. 4 relief panels made of green slate rested on top as a ceiling. They were decorated with tufts of palm or papyrus, spiral patterns and a double rosette frieze. Presumably a textile pattern was imitated. A fragment of this plate is now in the Berlin Collection of Antiquities . The side panels were also decorated in a similar way. The ceiling of the chamber, which probably served as a burial chamber, is said to have collapsed in 1869 with a loud rumble. There was another chamber above the adjoining room. Since the original entrance was walled up from the outside, it is assumed that this chamber only served to relieve the cover plates.

Comparison of the graves of the Mycenaean culture

In the dome graves, the Mycenaean sepulchral culture reached towards the end of the 16th century BC. Its climax. Before that, burials in shaft graves were common. During the 16th century BC The transition to the chamber carved into the rock with a long dromos took place . The access was closed with heavy stones after the burial. A new form of Mycenaean architecture emerged from the Mycenaean rock grave towards the end of the 16th century with the dome graves, the climax of which is the so-called "Treasure House of Atreus" in Mycenae. With a diameter of 14.5 m and a dome height of 13.8 m, it is also the largest known dome tomb. The grave of Orchomenos comes close to the Mycenaean model and surpasses it in the qualitative execution of the lateral burial chamber. In the other grave structures, pits in the floor of the dome or the dromos are common. In the dome graves of Vaphio and Dendra , burials were preserved intact. With their rich finds of weapons and jewelry, they give an impression of the equipment of Mycenaean warriors and kings at the beginning of the 15th century BC. Chr.

literature

- Carla M. Antonaccio: An Archeology of Ancestors. Tomb Cult and Hero Cult in Early Greece . Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham 1995, ISBN 0-8476-7941-1 , pp. 127-130 .

- Heinrich Schliemann : Orchomenos . Brockhaus, Leipzig 1881, p. 17–39 ( digitized version [accessed on July 28, 2015]).

- Christos Tsountas , J. Irving Manatt: The Mycenaean age. A study of the monuments and culture of pre-homeric Greece . London 1897, p. 126–129 ( digitized version [accessed August 6, 2015]).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Pausanias: Travels in Greece , 9, 38, 3