La Madeleine

La Madeleine is a settlement site in present-day France that was used for thousands of years up to the early modern period and was created about 5 km northeast of Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil on a narrow loop of the Vézère . It belongs to the municipality of Tursac , which is in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region - more precisely in the Dordogne department , the former province of Périgord . For the Upper Paleolithic period of the Magdalenian period , this important site functions as a type locality . It is located in the lower abri (rock overhang) below the chapel of the troglodytic village, dedicated to Saint Magdalena .

history

For more details on the prehistoric section see: La Madeleine (Abri)

Since the sea retreated from the eastern Aquitaine basin at the end of the Cretaceous period around 65 million years ago, Vézère, Dordogne, Lot and Tarn have cut deeply into the layers of limestone and chalk rock and the meanders of the river valleys known today with their steep walls and Abrises formed.

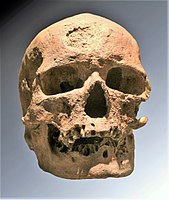

Around 17,000 years ago, Cro-Magnon people (named after the Cro-Magnon site in Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil and successor to the extinct Neanderthals ) settled in the abyss under the south-facing cliffs of La Madeleine at the level of the river Vézère down. These offered natural protection against the weather, the southern orientation warmed the settlement area. The open sides of the abrises could be closed with brushwood and furs or similar lightweight constructions. Caves also offered refuge in which people could use fire to protect themselves from predators. The area offered plenty of huntable food such as game and fish.

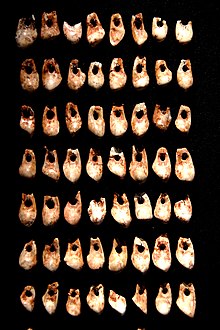

Prehistoric traces were found in La Madeleine in 1863. The grave of the “Child of La Madeleine” was a unique discovery. An excavation layer, dated between 20,000 and 12,000 before the beginning of our era, unearthed an abundance of arrowheads, stone and bone tools, jewelry and small works of art - as an example, a 10 cm large steppe bison (Bison priscus), in dynamic posture, on ivory (see photo at the top right). This epoch of the Upper Palaeolithic was named after the location of the finds representative of the time as the Magdalenian . A large selection of these finds is on display in the new National Museum of Early History in Les Eyzies-de-Tayac.

The excavations of the ruins of Roman village complexes and a villa near the Petit Marzac castle, above the settlement, are reminiscent of the Roman occupation of Aquitaine.

In the later centuries the inhabitants of the Périgord had to protect themselves not only from predators, but also from the warlike incursions of the Normans (= Vikings ) and Saracens . In the 8th century, the emergence of troglodytic settlements on the cliffs of La Madeleine is proven. For this purpose, existing naturally created cavities and abrises were used, a good distance above the valley floor or river bed, which were then expanded and shaped according to the needs of the future residents. The only open side of the cave was closed with a construction similar to the well-known half-timbering, made of wooden frames, wickerwork and straw clay. There were certainly also window and door openings in it. More comfortable dwellings or businesses were closed off with external walls made of stone masonry. The floor plan was subdivided with light walls made of wickerwork and clay or stone masonry.

Caves of greater heights received false ceilings made of wooden beams or had natural rock false ceilings. The lower level was intended for domestic animals such as sheep, pigs and poultry. The upper one served as a place to sleep.

The entrances to the troglodytic dwellings were mostly kept narrow and wooden walkways or ladders were often used. Such rather complicated approaches could be defended or removed with relatively little effort. In the Middle Ages this was used to create the drawbridges.

The origins of the small castle "Petit Marzac" on top of the rocky ridge go back to the 8th century. The castle gave the village of La Madeleine in the valley greater influence compared to other settlements.

Between the 8th and 13th centuries the village in the rocky slope experienced a considerable boom. Not only farmers lived here, but also traders with their families. Their everyday life consisted of fishing, livestock, growing vegetables, trading and building work to maintain and expand the homes. The river played a not insignificant role in this. Not only did it bring food and water, but it also provided shelter.

The brisk boat traffic on the Vézère with the so-called "gabarres" contributed to the economic success. The boats were not only used for fishing, they were also suitable for transporting large quantities of stones, for example for building castles, as well as wood, leather and other goods.

The establishment and operation of troglodytic settlements enabled the development of social structures.

In the 14th century, the Hundred Years War hit Aquitaine with blood and terror. Right at the beginning, the smoldering conflict between the French and the English broke out again openly. The village of La Madeleine and the castle belong to the family of those of Sireuil, who have to defend both against English attackers and marauding hordes several times. The defense system technology has been strengthened. Holes in the rock walls indicate that there were larger defenses that jutted out over the Vézère. At the time, the “main street” of the village was full of residents, soldiers and cattle.

In 1400 the Beynac de Tayac family took over the castle until it burned down in 1623 and all residents left the castle and village. Only one weaver family stayed on site. Every now and then shepherds or farmers sought refuge here at night. The last residents left La Madeleine at the beginning of the 20th century.

Details of La Madeleine

First settlement site

The troglodytic village of La Madeleine is roughly divided into two separate sections. The first settlement further to the east is a fairly large hall in terms of its area, which extends far into the rock background. Spread over the entire floor area are loosely lying and heaped stones, supplemented by huge boulders that have once detached from the ceiling. From the piles of stones, bricked-up wall pieces protrude from which one can guess the floor plan of a residential building. A brick arch of a former oven can also be seen.

A chiseled channel on the upper rock wall provided the water supply. In front of the cave, a place for an observation post was created by means of a wooden construction.

Second settlement site

If you follow the connecting path between the two settlements in a westerly direction, you come across the second, much larger settlement, and the actual "main street", which begins with a wooden bridge (removable for defense) and then leads past all the houses on the settlement area. Drainage channels for draining rain and sewage from the residents and post holes for roofing the main road are mortised into the street. Most of the outer walls of the troglodytic dwellings in La Madeleine were fitted with massive masonry, possibly later, in order to thwart any attacks on the settlement from the valley floor or from boats. Together with the roofing of the "main street", the dwellings were protected from arrow shots, especially those with incendiary devices.

First house

In the first open cavity there is an intermediate ceiling made of rock, which has been carved out of the solid rock material in a complex chiselling process. The low height of the resulting lower floor suggests only small pets. There are feeding troughs embedded in the rock. The first layers of the outer wall indicate that the entire outer wall was made of stone masonry up to the outer edge of the rock ceiling, as was the case with the two adjoining houses.

The kitchen

The kitchen was in use until the 18th century. It was the center of the village and everyone was fed from here. You can see an oven, a fireplace for cooking and smoking meat and fish, and a chest carved into the rock. There is also a large round stone vessel on the floor in a corner of the room. The meaning of the holes and depressions made in the bedrock are still unclear today. The smoke that gathered under the ceiling was drawn outside through an opening above the door. The rock face above still has black soot traces.

It can be assumed that the people working in the kitchen were highly regarded by the residents.

The weaver house

The weaver lived and worked in this room. The holes and depressions in the floor are probably the mounts for the loom and other equipment. The weaver and his family were able to make clothes for all villagers from sheep's wool, flax and hemp.

The Sainte-Madeleine chapel

The Sainte-Madeleine chapel is immediately behind the weaver's house. The “main street” leads below the chapel through a vaulted passage to the housing of the settlement behind. Noble families from the castle and the village had the old troglodytic chapel expanded. A second chapel was built on the outlines of a former Romanesque chapel - in the Gothic style, clearly recognizable by the ribbed vault . There are two Romanesque altars under the windows on the east side. The walls were decorated with frescoes, of which only the so-called "sundial" (?) Has survived.

A document from 1737 shows that “the castle and the surrounding area was sold by Mademoiselle Elisabeth-Rosalie d'Estrée de Tourbe to Arnaud Simon-Claude d'Estanges, Marquis of Sainte Alvère, who then opened the chapel to the villagers and she dedicated it to Sainte-Madleine. ”On the opposite side of the chapel, an enclosed staircase leads up to the church in eight steps.

More dwellings

Behind the chapel, the “main street” continues its previous course and leads past the single-storey masonry walls of stables; The ceiling beams for the second floor with the residents' beds are still on the walls. In front of the street-parallel walls, one can still see the foundation walls of the outer walls in the street surface, which run directly vertically under the outer ceiling edge of the demolition.

Assembly place

The “main street” then widens to a place that was probably used for gatherings of the villagers and the rule of the castle. The survey applied to the ground should have given a speaker, such as a mayor or judge, a better overview and a better hearing.

Sporadic fountain

Immediately behind it is a hollow at waist height, a well that was fed by unknown tributaries and only surged up sporadically.

Spy nest

At the end of the street, high up on the vertical rock wall, you can see a rectangular window with a cavity behind it. This was the sheltered place of a scout, who from here had an excellent view of the entire loop of the river. This observation post is just one of many that are placed along the meandering Vézère so that every scout can see and hear the nearest upstream or downstream. In uncertain times, the alarm could be given with blow horns or trumpets, in the dark also with torches, which was then understood by all residents of the villages on the river, as far as the scout chain reached. This was of the greatest importance in times of threat from the "Northmen", Saracens and later the English.

The "Petit Marzac" castle and its defense system

The castle is built directly on the stand and occupies an area of 400 square meters, excluding the moats. The floor plan of the castle is rectangular, its long side facing the Vézère stands directly on the edge of the 40-meter vertically sloping rock wall. Seen from the river, the transition between the rock face and the castle masonry is flowing, the walls seem to grow up out of the steep face. At the eastern end of this outer wall and in its extension, a narrow component protrudes, closed off by a slim round tower. This construction is a kind of Vorwerk (barbacane) to monitor and defend the immediately adjacent castle entrance - always an alleged weak point in the defense system that is attacked first. At the same time one could control the access over the footbridge to the troglodytic part of the village 2 and to the "main street". The entrance portal to the castle was dimensioned so that mounted persons and wagons could pass it. In front of the portal the usual drawbridge, which was raised or lowered as required.

The castle is a three-part defense system consisting of a bailey, a refuge and the last possibility of retreat, the donjon (keep).

The outer ward is the most spacious part of the fortress right behind the portal, in an L-shaped floor plan, with buildings for the daily needs of the armed forces, horses, food animals and other supplies.

The square refuge castle is enclosed by it on both sides , which, without a case of defense, served together with the donjon for living and sleeping of the rulers. If the attackers overpowered the portal and outer bailey, the remaining defenders retreated here, and a small round tower on the corner of the wall offered additional protection. A passage carved into the rock and leading from the outer bailey to the donjon helped the last defenders to escape.

In the western corner of the castle on the mountain side is the massive round donjon , the building with the thickest and tallest walls, half of which is erected once behind and another time in front of the defensive walls. The keep and its highest rooms were the last refuge of the residents of the castle. The construction of the tower protruding in front of the outer wall guarantees a spacious overview of the surroundings from the loopholes and a corresponding coverage of the defenders' field of fire. Below the donjon there is a drinking water reservoir dug into the rock, formerly fed by a spring above the castle. This ensured that the precious liquid was supplied to the end. This spring also served as a safe drinking water supply for the entire village.

In front of the castle's three defensive walls, which did not border the steep wall, deep moats kept the attackers at bay. The ongoing guarding of the castle could be limited to the battlements on these three sides, as the river side was not attacked anyway because of the high rock walls.

Today you can only see the remaining ruins of the castle and its defensive moats, largely overgrown by the green vegetation, which "knows no mercy" when the masonry parts were broken down by bursting roots.

The vegetable garden

Opposite the castle entrance between the two settlements was the vegetable garden, which is still maintained today. Not only were vegetables grown here to feed the population, but medicinal medicinal plants were also cultivated. As the population grew, fields were also created outside the settlement areas. The garden is somewhat hidden so that it could still be used in the event of enemy attacks. Possibly the garden was a kind of communication center for the villagers, perhaps a kind of market place, near which the cattle could be tied to stone rings.

Web links

swell

- France, the southwest, the landscape between the Massif Central, Atlantic and Pyrenees, Julia Droste-Hennings, Thorsten Droste, DUMONT Art Travel Guide, 1st edition 2007, DuMont Reiseverlag Ostfildern

- Guide text of the museum kiosk, duplicated leaflets, 13 A4 sheets with photos, without indication of author; poorly translated into German; will be returned after viewing.

Coordinates: 44 ° 58 ′ 5.7 " N , 1 ° 1 ′ 58.6" E