Malinche

La Malinche (* around 1505 near Coatzacoalcos ; † around 1529 in Tenochtitlan ), called Malintzin or Malinalli in Indian and baptized Marina by the Spaniards , played an important role as the interpreter and later lover of the conquistador Hernán Cortés during his campaign of conquest . Cortés himself was also called "Malinche" by Moctezuma for example .

Surname

The Spanish chroniclers do not mention her Indian name, in oral traditions she is mostly called Malintzin or Malinalli . This suggests that, as is customary among the Aztecs , at birth she was given the name of the day she was born. Malinalli is the twelfth of the twenty “weeks” in the 260-day ritual calendar tonalpohualli (there was this “sacred calendar” interlocked with the xiuhpohualli, which is based on the rotation of the sun, with 360 days for most Mesoamerican peoples). This “week name”, also known as the day symbol, was preceded by the number of the day (in the order from 1 to 13), for example: Ce Malinalli (“one grass”).

It is not known whether the native population gave it the suffix -tzin before or after it was given to Cortés. It expresses respect, appreciation and awe and often appears in connection with gods and nobles, e.g. B. Tonantzin ("Our adored mother", nickname of the earth goddess Coatlicue ); Topiltzin ("Our Revered Prince", title of the priestly prince Quetzalcoatl of Tula); Matlalcihuatzin (name of the mother of Nezahualcóyotl , poet and ruler of Texcoco).

The Spaniards only called her Doña Marina , and Hernán Cortés never called her otherwise in his letters to Emperor Charles V. Usually the Native American name was not taken into account when natives were baptized, but here the similar sound may have played a role in view of their prominent position.

Life

slave

Malinche was born in 1505 near Coatzacoalcos (on the Gulf coast of the isthmus of Tehuantepec ), where her parents, who are assigned to the Indian nobility, are said to have ruled Painala and other localities as caciques .

Even as a child, Malinche's life was tragic. After her father died, her mother remarried and had a son. Malinche's mother probably wanted to secure the right to the family inheritance for her son instead of the firstborn Malinche, so the girl was sold by her mother to Maya slave traders from Xicalango further east. The mother spread the rumor that her daughter had died. Later on, Malinche must have been sold or abducted to Tabasco . Nothing is known of Malinche's time in Tabasco.

After the expedition commanded by Cortés went ashore in Tabasco in 1519, the Spaniards were attacked by the Maya, who were defeated by the conquistadors after a fierce battle. The defeated Indians gave Cortés twenty female slaves on March 15, 1519 as a token of their respect, along with some valuables . Among them was Malinche.

After the principles of the Christian religion were explained to the slaves, they were baptized and given Spanish names. Malinche was now called Doña Marina . The city of Tabasco was given the new name Santa Maria de la Victoria during these celebrations . After the baptism , the slaves were distributed to the Spanish officers. Cortés gave Malinche to Alonso Hernández Portocarrero, one of his officers.

Interpreter for Hernán Cortés

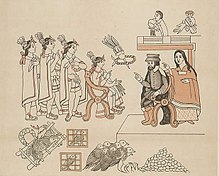

On the island of Cozumel , the Spanish expedition met Gerónimo de Aguilar , a Spaniard who had lived as a slave in Mayan captivity for eight years. He initially served Cortés as his only interpreter. When the conquistadors entered the territory of the Aztecs , where Nahuatl was spoken in contrast to the Maya, his services became worthless. During this time, Cortés learned that Malinche knew both Nahuatl - probably her mother tongue - and the language of the Maya, of which she had long been a slave. This must have been a stroke of luck for Cortés, because communication with the Aztecs and their vassals could only be ensured with Malinche's help. Malinche knew the way of thinking of the peoples of Mesoamerica. She translated Cortés' words and often supplemented them with her own added explanations. When Cortés met Aztecs or other Nahuatl-speaking peoples during his expedition, Malinche first translated the Nahuatl Aztec or Tlaxcaltek ambassadors into the Maya language and Aguilar finally translated this into Spanish. Malinche soon learned Spanish himself, and Aguilar's services in this complicated chain of communication became superfluous.

As an interpreter, Malinche was always close to Hernán Cortés. Presumably from the summer of 1519 she was also his lover. The conquistador was soon by the Indians Capitán Malinche called - Capitán because they perceived him as their ruler.

Especially at the beginning of the campaign, Malinche was immediately present at every battle and shared the danger of death with the Spaniards. When Cortés was attacked by the Tlaxcalteks, she lifted the men up in battle if they lost heart. When Xicotencatl sent spies into the Spanish camp, it was Malinche who exposed these men during the interrogation. Hernán Cortés then had the hands of the Tlaxcaltec spies chopped off and sent them back in this condition.

At the historic encounter between Cortés and Moctezuma II , it was the slave Malinche who raised her voice to the Aztec ruler and proclaimed the words of the conquistadors.

The importance of Malinche for Cortés becomes clear in the Noche Triste . During the loss-making escape from Tenochtitlán , he had her and other women protected by three hundred Tlaxcalteks and thirty Spaniards. Malinche was one of the first to reach the safe shore in the vanguard. Many other women and two thirds of the Spanish armed forces lost their lives that night.

Through Malinche's interpreting services, Cortés obtained crucial information and, through diplomatic skills, was able to win the caciques of peoples who originally owed tribute to the Aztecs as his allies. Ultimately, an armed force composed mostly of Indian soldiers emerged, which was able to conquer the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán, today's Mexico City , in August 1521.

Why Malinche helped the Spanish conquerors is not clear. Possible motives are their gratitude for the liberation from slavery, their disgust for the Aztecs, the Quetzalcoatl myth, according to which the indigenous people believed Cortés to be a god or prince whose return across the sea is said to have been prophesied, Malinche's Christian faith and her love for Cortés.

In 1523, Malinche reunited with her brother and mother, whom she had sold into slavery. The two had converted to the Christian faith and now called themselves Lázaro and Marta. Malinche was the most powerful woman in New Spain at the time and had an incredible influence on Cortés. It was in great fear that her brother and mother met her in Painala, Malinche's birthplace near Coatzacoalcos. At this meeting they feared for their lives, but Malinche forgave them.

Mother and wife

Around 1523, Malinche gave birth as the lover of Hernán Cortés, his first son Martín , who was to grow up separately from his mother.

On October 20, 1524, Malinche married Juan Xaramillo de Salvatierra , an officer from Cortés' environment, during the Honduras campaign. After her return, she lived with her husband in Tenochtitlán until her death. With Xaramillo de Salvatierra she had another child, her daughter María. Fewer sources are known from this period than from the time of Cortés' campaign against Moctezuma. The year of her death (probably 1529) is not clearly documented, the circumstances of death are unknown.

reception

Cortés only briefly mentioned Malinche in his letters and later writings. The essential source for the biography of Malinche up to the conquest of Tenochtitlán is the report that Bernal Díaz del Castillo , a soldier of Cortés, wrote down in his history of the conquest of Mexico . He described her importance for the Spaniards with the words: “This woman was a crucial tool on our voyages of discovery. We have only been able to accomplish a lot with God's help and help. Without them we would not have understood the Mexican language, we simply could not have carried out numerous activities without them. "

La Malinche's house, where Cortés and his Indian lover once lived, is still in a neighborhood in Coyoacán.

In today's Mexico, the Indian Malinche enjoys a very divided esteem, some even see her as one of the most controversial women in world history. While the Aztec and Tlaxkaltek chronicles written after the conquest still paint a positive image of Malinche, the term malinchismo has stood for betrayal of one's own people since the rise of Mexican nationalism in the 19th century . Other Mexicans see her, incorrectly referred to as the mother of the first mestizo , a kind of mother of the nation (the mestizos now make up the majority of the Mexican population). Both attitudes are certainly to be assessed as modern perspectives that presuppose a Mexican nation or also want to emphasize its particularity by delimiting it from the land of the conquistadors; a nation that didn’t exist at least at the time of Malinche.

Malinche's colorful résumé made her go down in the folklore and legends of Mexico. Many places in Mexico perform annual Malinche dances ; the figure of la llorona (the one who weeps ), whose spirit wanders restlessly in the streets of Mexico City and weeps for her children, is often associated with Malinche.

Malinche's name also bears the Malinche volcano on the border of the states of Tlaxcala and Puebla , one of the highest mountains in Mexico.

literature

- Anna Lanyon: Malinche - The other story of the conquest of Mexico . Ammann, Zurich 2001 ISBN 3-442-72909-2

- Barbara Dröscher, Carlos Rincón (ed.): La Malinche. Translation, interculturality and gender , edition tranvía, 2nd edition, Berlin 2010 (1st edition: 2001), ISBN 978-3-938944-43-1

- Carmen Wurm: Doña Marina, la Malinche. A historical figure and its literary reception . Burned up. Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 978-3-96456-698-0 , (accessed via De Gruyter Online)

Web links

- motecuhzoma.de

- Malinche, most ambivalent interpreter in history

- Spektrum .de: A homeless person who betrayed her home? October 26, 2019

Individual evidence

- ↑ William H. Prescott : The Conquest of Mexico . DBG , Berlin 1956, p. 336 u. a.

- ↑ Hanns J. Prem: The Aztecs: History - Culture - Religion. Verlag CH Beck, p. 107.

- ↑ a b Bernal Díaz del Castillo: History of the Conquest of Mexico , 1988, p. 96.

- ↑ Cortés, Hernán: The Conquest of Mexico. Three reports to Kaiser Karl VS 38.

- ^ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: History of the Conquest of Mexico , 1988, p. 135.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: History of the Conquest of Mexico , 1988, p. 168.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: History of the Conquest of Mexico , 1988, p. 357.

- ↑ Carmen Wurm: Doña Marina, la Malinche. A historical figure and its literary reception . Burned up. Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 978-3-96456-698-0 , p. 29 (accessed from De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: History of the Conquest of Mexico , 1988, p. 98.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Malinche |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Marina; Doña Marina; Malintin; Malinalli |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Indian interpreter and lover of the Spanish conqueror Hernán Cortés |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1505 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | at Coatzacoalcos |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 1529 |

| Place of death | Mexico city |