Gastric laryngitis

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| J37.0 | chronic laryngitis |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

Under laryngopharyngeal reflux refers to a non-bacterial inflammatory reaction of the mucosa of the larynx and surrounding by a throat (lat. Refluxus "reflux") Reflux of gastric secretion , particularly in the gastric acid and pepsin are essential components. The name of the disease is derived from the Latin "larynx": larynx , "-itis": ending for inflammation and "gaster": stomach . Other names are silent reflux , laryngitis posterior , laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) , NERD ( non esophageal reflux disease) or EERD (extra esophageal reflux disease).

Causes and complaints

The main cause of gastric laryngitis is gastroesophageal reflux ( GERD , gastroesophageal reflux disease), in which stomach contents enter the esophagus . The stomach acid it contains causes damage to the esophagus as well as the vocal cords and mucous membranes .

Typical complaints are:

- Voice problems and hoarseness

- Lump feeling in the throat

- Clear throat

- chronic dry cough

Findings

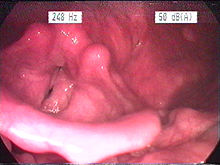

In the magnifying glass laryngoscopic image, hyperplasia of the mucous membranes predominantly of the posterior (rear) parts of the larynx, the esophageal entrance and the back and side walls of the pharynx are evident. A light coloration and wrinkling of the mucous membranes is typical; due to the thickening, the piriform recess does not unfold as well. Depending on the lying habits, a preference for one side can be observed due to predominantly nocturnal reflux. In more recent, experimental studies, negative effects of reflux on the microstructure of the laryngeal mucosa have been demonstrated. The gastric juice leads to a reduced resistance of the mucosal barrier with the result that pollutants can penetrate more easily into deeper cell layers. Another study showed changes in the immune system of the mucous membrane (in so-called killer cells ) as a result of reflux.

Diagnosis

The endoscopic image is still the standard, even if individual studies have shown that the findings can be very variable and therefore led to different interpretations by different examiners. The 24-hour pH-metry counts as an instrumental examination for the direct detection of reflux , whereby the classic probes with measuring points in the stomach and lower esophagus are not optimal, since only one measuring point in the hypopharynx can record the reflux in the target region. Therefore, special measuring probes with an appropriate configuration are more suitable. A gastroscopy is required to generally clarify a cause (e.g. hiatal hernia ) (see also reflux oesophagitis ). Even non- obstructive snoring can promote reflux, since the obstruction of the airways creates a considerable pressure gradient from the stomach to the thorax / throat. The thoracic negative pressure during (frustrated) inspiration increases considerably, the gastric juice is sucked upwards. Therefore, a polysomnography in the sleep laboratory , ideally with somnoendoscopy , may be necessary.

Spread and socio-economic consequences

Research has shown that around 20% of Americans have reflux down to the throat. Pahn found signs of gastric laryngitis in 41% of 1000 patients who came to the outpatient clinic because of a voice disorder, while conversely 10% of patients with esophageal reflux also complained of globus sensation, throat clearing and abnormal sensations in the larynx area. There are therefore estimates of the socio-economic consequences of this disease: according to an audit by the British National Health Services , around 4% (equivalent to approx. € 24 million) of the expenditure on proton pump inhibitors is spent on this form of reflux. There are also studies on the reduced quality of life by gastric laryngitis. In addition, patients with gastric laryngitis have an increased risk of developing carcinoma in the larynx. According to a 2018 US epidemiological study of elderly patients, there is an association between gastroesophageal reflux and carcinoma in the lower aerodigestive tract. However, this epidemiological connection must be checked with regard to causality. Therefore, patients with gastric laryngitis, especially those with other risk factors such as nicotine and alcohol consumption , should be monitored long-term for tumor development.

therapy

To date, there are no valid studies on therapy, many show qualitative deficiencies and the results are very heterogeneous. Nevertheless, drug treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is the therapy of choice internationally . Since reflux, which is harmful to the larynx, occurs predominantly at night, an evening dose is (also) described as useful. However, recent studies show that PPIs are no better than placebo. At the same time, studies show that not only the acid in the reflux, but also the pepsins it contains play a major role in the development of symptoms. Since PPIs only suppress acid production and not pepsins, PPIs are inadequate as a treatment measure. Therefore, the medical importance of nutritional therapy and surgery is increasing compared to PPIs. In this way, the reflux itself and thus the flow of pepsins into the throat, airways and larynx can be stopped. If snoring is relevant, CPAP therapy leads to a significant improvement in the appearance of the laryngeal mucous membrane. Depending on the other complaints (esophagus, bronchi), additional, organ-specific therapeutic measures are required. In the case of secondary voice disorders induced by the mucosal stress , after the changes in the mucous membrane have improved, voice therapy is indicated.

literature

- Jürgen Wendler, Wolfgang Seidner, Ulrich Eysholdt: Textbook of Phoniatry and Pedaudiology . 4th edition. Thieme-Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-13-102294-9 .

- JP Pearson, S. Parikh, RC Orlando, N. Johnston, J. Allen, SP Tinling, N. Johnston, P. Belafsky, LF Arevalo, N. Sharma, DO Castell, M. Fox, SM Harding, AH Morice, MG Watson, MD Shields, N. Bateman, WA McCallion, MP van Wijk, TG Wenzl, PD Karkos, PC Belafsky: Review article: reflux and its consequences - the laryngeal, pulmonary and oesophageal manifestations. Conference held in conjunction with the 9th International Symposium on Human Pepsin (ISHP) Kingston-upon-Hull, UK, 21-23 April 2010 . In: Aliment Pharmacol Ther . 33 Suppl 1, 2011, p. 1-71 , PMID 21366630 ( wiley.com [PDF]).

Individual evidence

- ↑ E. Erickson, M. Sivasankar: Simulated Reflux Decreases Vocal Fold Epithelial Barrier Resistance. In: Laryngoscope. 2010 August; 120 (8), pp. 1569-1575. Free article

- ^ A b LE Rees, L. Pazmany, D. Gutowska-Owsiak, CF Inman, A. Phillips, CR Stokes, N. Johnston, JA Koufman, G. Postma, M. Bailey, MA Birchall: The mucosal immune response to laryngopharyngeal reflux. In: Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Jun 1; 177 (11), pp. 1187-1193. Free article

- ↑ a b BT Green, WA Broughton, JB O'Connor: Marked improvement in nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux in a large cohort of patients with obstructive sleep apnea treated with continuous positive airway pressure. In: Archives of Internal Medicine . 2003 Jan 13; 163 (1), pp. 41-45. Free article

- ↑ P. Demeter, A. Pap: The relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and obstructive sleep apnea. In: Journal of Gastroenterology . 2004 Sep; 39 (9), pp. 815-820. PMID 15565398

- ↑ AM Zanation, BA Senior: The relationship between extraesophageal reflux (EER) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). In: Sleep Medicine Reviews . 2005 Dec; 9 (6), pp. 453-458. PMID 16182575

- ↑ JA Koufman, MR Amin, M. Panetti: Prevalence of reflux in 113 consecutive patients with laryngeal and voice disorders. In: Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery . 2000; 123, pp. 385-388. PMID 11020172

- ↑ J. Pahn, A. Schlottmann, G. Witt, W. Wilke: Diagnostics and therapy of laryngitis gastrica. In: ENT. 2000, 48, pp. 527-532. PMID 10955230

- ↑ N. Connor, K. Palazzi-Churas, S. Cohen, G. Leverson, D. Bless: Symptoms of extraesophageal reflux in a community-dwelling sample. In: J Voice. 2007; 12, pp. 189-202. PMID 16472972

- ↑ Vaezi MF, Qadeer MA, Lopez R., Colabianchi N.: Laryngeal cancer and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a case-control study. In: Am J Med. 2006; 119, pp. 768-776. PMID 16945612

- ^ Charles A. Riley, Eric L. WU et al .: Association of gastroesophageal reflux with malignancy of the upper aerodigestive tract in elderly patients . In: JAMA Otolaryngolgy-Head & Neck Surgery . tape 144 , no. 2 , February 2018, p. 140-148 , doi : 10.1001 / jamaoto.2017.2561 ( jamanetwork.com [accessed January 9, 2019]).

- ↑ M. Ptok, A. Ptok: Laryngopharyngeal reflux and larynx-associated complaints . In: ENT . tape 60 , no. 3 , 2012, p. 200–205 , doi : 10.1007 / s00106-011-2441-6 , PMID 22402900 .

- ↑ JS Lee, YC Lee, SW Kim, KH Kwon, YG Eun: Changes in the Quality of Life of Patients With Laryngopharyngeal Reflux After Treatment . In: Journal of Voice . 2014, doi : 10.1016 / j.jvoice.2013.12.015 , PMID 24598356 ( online ).

- ↑ J. Waxman, S. Yalamanchali, ES Valle, T. Pott, M. Friedman: Effects of Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy for Laryngopharyngeal Reflux on Posttreatment Symptoms and Hypopharyngeal pH . In: Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2014, PMID 24647643 ( sagepub.com ).

- ↑ C. Reimer, P. Bytzer: Management of laryngopharyngeal reflux with proton pump inhibitors . PMC 2503658 (free full text).

- ↑ reflux gate . Differences in the treatment of GERD and silent reflux .