esophagus

The esophagus ( ancient Greek οἰσοφάγος oisophágos , German 'throat, esophagus [through which the food is carried]' , Latin esophagus , Germanized also esophagus , obsolete swallowing intestine ) is a muscular tube that is surrounded by connective tissue on the outside and lined with mucous membrane on the inside. It is part of the digestive tract and, in the last phase of the act of swallowing , uses peristaltic movements to transport food from the throat to the stomach .

In humans, the esophagus is about 25 centimeters long and has a diameter of about 1.5 centimeters at the narrowest point. It begins at the level of the larynx , runs down between the windpipe and the spine into the posterior mediastinum in the chest , where it lies close to the left atrium of the heart and then passes through the esophageal slit of the diaphragm into the abdominal cavity and opens into the stomach.

The lower end of the esophagus is closed at rest so that no acid stomach contents flow back into the esophagus. In heartburn , the esophagus is not properly closed, and frequent reflux is known as reflux disease or reflux esophagitis , and it can cause esophageal cancer . This occurs less often than other cancers such as lung or colon cancer , but remains undetected for a long time due to its unspecific symptoms and therefore has a high mortality rate. Inflammation of the esophagus manifests itself as a burning sensation behind the breastbone , which is very similar to the angina pectoris in coronary artery disease .

Anatomy of the esophagus in man

Location and structure

The esophagus is about 25 centimeters long in adults. It begins at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra at the lower edge of the cricoid cartilage of the larynx and flows into the stomach shortly after passing through the diaphragm at the level of the tenth thoracic vertebra .

According to its course, the esophagus is anatomically divided into three sections. The part of the esophagus between its beginning in the larynx and its entry into the chest is called the neck part (pars cervicalis) . It is about eight inches long. In the chest it runs first in the upper, then in the posterior mediastinum and passes through a slit (hiatus oesophageus) through the diaphragm. This section of the chest (pars thoracica) is about 16 centimeters long. The length of the abdominal part (pars abdominalis) between the passage through the diaphragm and the entry into the stomach is variable due to the sliding installation in the esophageal slit and varies between one and three centimeters.

The esophagus is in close spatial relationship with other important structures and organs. In the neck, the windpipe lies directly on the front (ventral) until the windpipe divides into the two main bronchi at the level of the fourth thoracic vertebra. Below the division point ( bifurcatio tracheae , tracheal fork), i.e. in the lower mediastinum, the esophagus is separated from the left atrium of the heart by the pericardium . Also at the level of the tracheal fork, the aorta arises from the left ventricle, bends backwards (dorsally) over the left main bronchus and runs downwards (caudally) to the left of the esophagus along the spine , displacing the esophagus somewhat to the right. Also below the tracheal fork, the left and right vagus nerves attach to the esophagus and disintegrate into two nerve plexuses , the vagal trunks . The esophagus is rotated clockwise in its course up to the stomach, so that the left vagus nerve comes to lie on the front of the esophagus as the anterior vagus trunk and the right vagus nerve as the posterior vagus trunk on the back of the esophagus.

While the neck part of the esophagus is still close to the spine , the chest part is increasingly moving away from it. Before it joins the stomach, the esophagus crosses the aorta from right to left; when it passes through the diaphragm, it lies roughly in the middle in front of her.

The course of the esophagus and its close proximity to other organs result in three constrictions. The uppermost point is also the narrowest part of the esophagus: the mouth of the esophagus ( constrictio pharyngooesophagealis , constrictio cricoidea or angustia cricoidea ). It lies at the level of the cricoid cartilage of the larynx and has a diameter of about 1.5 centimeters. From the ring cartilage from radiation muscles around wrap around the esophageal sphincter and him as a sphincter muscle (sphincter) close. The shutter is supported by a venous plexus in the submucosa (see below section trim for histology). The upper narrow of the esophagus is closed at rest. The chest part is constricted by the left main bronchus and the aortic arch, which is why this middle constriction is also called "aortic narrowing" ( Angustia aortica or Constrictio partis thoracicae ). The third tightness is the tightness of the diaphragm ( constrictio diaphragmatica or constrictio phrenica ). Here the esophagus is elastically connected to the diaphragm by the phrenicooesophageal ligament (Laimer's ligament).

The lower opening of the esophagus is closed at rest due to its longitudinal tension. But it doesn't actually have a sphincter muscle. One speaks of angiomuscular expansion , because in the lowest esophageal segment there is a plexus of veins directly under the epithelium of the mucous membrane. This occlusion opens when the esophagus shortens when swallowing, thereby reducing the longitudinal tension locally. The steeply positioned confluence level of the esophagus tilts into the stomach, with the pivot and fixed point in front of the passage through the diaphragm and a loose sliding layer (also called bursa infracardiaca) in the rear hiatus of the diaphragm enables this. A reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus can only be produced experimentally by tilting or by a horizontal position of the confluence plane, not by removing the His angle, which lies between the longitudinal axis of the esophagus and the gastric fundus. In newborns / infants, it is almost horizontal, and increased pressure in the abdomen in the case of obesity and advanced pregnancy shifts the level of the junction and facilitates reflux of stomach contents.

Blood supply and lymph drainage

The blood supply takes place according to the division into neck, chest and abdomen. The neck part receives branches from the lower thyroid arteries ( arteria thyroidea inferior ) , the venous blood flows through the lower thyroid veins (vena thyroidea inferior) or directly into the vena brachiocephalica . From here the blood reaches the superior vena cava ( superior vena cava ) . The chest part is supplied with oxygen-rich blood via direct branches of the aorta, its venous blood reaches the azygos and hemiazygos veins, both of which also flow into the superior vena cava. The abdominal part is reached by branches of the left gastric artery and vein ( arteria gastrica left and vena gastrica left left ). It is important here that the blood drains into the portal vein ( Vena portae hepatis ) , but the branches of the gastric vein are connected to the branches of the azygos vein through the plexus of the lower esophageal sphincter. If the outflow of the portal vein is interrupted in the case of liver cirrhosis , for example , the esophageal veins serve as an important bypass route ( portocaval anastomosis ). The swollen veins are recognizable as esophageal varices and are the site of life-threatening bleeding if they tear.

Lymph flow also varies from section to section. Basically entering lymph to nearby at the esophageal lymph nodes , the nodules lymphoidei juxtaoesophageales . In the neck part, these drain into the deep cervical lymph nodes (Nll. Cervicales profundi) . The lymphatic drainage of the chest is in two directions: from the upper (cranial) half towards the head into the bronchomediastinal trunk , and from the lower (caudal) half caudally via the diaphragmatic lymph nodes into the bronchomediastinal trunk . The lymph nodes of the lower part of the chest have connections with the lymph nodes of the stomach part, so that a small part of the lymph of the chest part gets into the lymph nodes of the stomach part. From here the lymph flows via the lymph nodes along the left gastric artery to the celiac lymph nodes on the celiac trunk . Changes in position and pressure can reverse this direction of flow, so that lymph from the abdominal section can also reach the bronchomediastinal trunk via the diaphragmatic lymph nodes . This mechanism is responsible for the spread of gastric cancer - metastasis of importance.

Innervation

The esophagus is sympathetically and parasympathetically innervated, whereby the peristalsis and the glandular secretion are inhibited (sympathetic) or increased (parasympathetic). The nerves do not innervate the smooth muscles directly, but rather influence the activity of the enteric nervous system , which controls the smooth muscles. The striated muscles , which can be found mainly cranially, are controlled directly by motor nerve fibers of the vagus nerve and the recurrent laryngeal nerve . The parasympathetic nerve fibers for the enteric nervous system and the sensitive fibers from the tissue to the brain run along with these nerves . The sympathetic fibers come from the stellate ganglion and from the cranial trunk ganglia of the thorax.

Feinbau

The esophagus shows the typical wall structure of the gastrointestinal tract with four layers. The innermost layer is a mucosa ( tunica mucosa , short mucosa ), which in turn is composed of three layers: the surface is covered with epithelium (epithelial layer) covering the by loose connective tissue ( lamina propria mucosae) by a layer of smooth muscle cells (Lamina muscularis mucosae) is separated. The mucous membrane rests on a loose layer of connective tissue ( tunica submucosa , or submucosa for short ). This leads the blood and lymph vessels for the mucosa and contains a nerve plexus, the submucosal plexus . It also serves as a shifting layer to the third wall layer, the tunica muscularis . This muscle layer has an interwoven fiber system, the morphological unit of which is the apolar helical fiber. The ascending and descending fibers can be directed clockwise and counterclockwise. The tunica muscularis is consequently a three-dimensional network and does not show an isolated bilayer in the longitudinal and circular muscle layers. Such findings are artifacts because the isolated organ esophagus is shortened by almost a third.

Another nerve plexus is embedded in the muscle fiber network, the myenteric plexus, which, like the submucosal plexus, belongs to the enteric nervous system.

Outside the muscle layer, there is additional loose connective tissue in the esophagus ( tunica adventitia , or adventitia for short ), which anchors the esophagus in the area. Only shortly before the transition into the stomach is the esophagus covered by the peritoneum and has no adventitia .

The fine structure of the esophagus shows some differences to the other sections of the digestive system, which are due to the mechanical stress caused by the transported food and mainly affect the mucous membrane. Characteristic is the multi-layered uncornified squamous epithelium , the larger proportion of collagen fibers in the lamina propria , which becomes firmer as a result, and a stronger mucous membrane-muscle layer (lamina muscularis mucosae) . The mucous glands (glandulae oesophageae) that produce lubricating mucus are located in the submucosa . The mucous membrane is strongly thrown into longitudinal folds, which serve as a reserve for stretching larger chunks of food.

Another peculiarity of the human esophagus is that the muscular layer (tunica muscularis) in its upper third is formed by striated muscles . Smooth muscle cells are only found in their lower third, with the smooth transition in the middle third.

At the cardia , the transition to the stomach , there is a sharp boundary between the squamous epithelium of the esophagus and the epithelium of the stomach.

Esophagus in animals

The anatomy of the esophagus in mammals largely corresponds to that of humans, except for differences in size. The main difference is the extent of striated and smooth muscles in the muscle layer. In ruminants and dogs , for example, the entire esophagus is formed by striated muscles, in pigs only a narrow strip of smooth muscles is formed directly at the stomach entrance, while in horses and cats (as in humans) smooth muscles are formed in the gastric third.

In birds , the esophagus is on the right side of the neck. Its wall is thin and wrinkled so that it is very stretchy. On the head side there is often a section with cornified squamous epithelium. Some bird species have an inflatable esophageal dilatation, which is presented at courtship . Another peculiarity of the esophagus of birds is the goiter (ingluvies) . This extension is located at the breast entrance and serves to store food, the pre-swelling of the feed, in some species such as pigeons it forms the crop milk to nourish the chicks.

Development and malformations

The esophagus emerges from the foregut from the fourth week of development of the embryo . From this point on, the lung bud sprouts out of the foregut . The system of the lungs and windpipe ( trachea ) is initially connected to the foregut along its entire length, but is then constricted by the growing in of a partition, the esophagotracheal septum . The foregut is now divided into an abdominal (ventral) and a back (dorsal) tube. The esophagus develops from the dorsal part. The muscular layer of the esophagus arises from the surrounding mesenchyme .

Malformations of the esophagus are often caused by a defective formation of the esophagotracheal septum . Mention should be made here of the esophageal atresia , in which the esophagus ends blindly and does not establish a connection between the throat and stomach, and the tracheo-esophageal fistula , in which a connection between the trachea and esophagus remains. In about 90% of cases, these disorders occur in combination, that is, the upper section of the esophagus ends blindly, while the lower section has a connection to the trachea. The esophageal atresia prevents the amniotic fluid from draining from the amniotic cavity , causing excessive fluid to accumulate in it ( polyhydramnios ). In newborns with esophageal atresia, fluid can enter the windpipe and lungs after the first drink and cause pneumonia ( aspiration pneumonia ). If the diagnosis is made in good time, the malformation can be remedied by surgery. Inadequate growth in length of the esophagus is also possible; in this case it can pull the stomach through the esophageal slit (hiatus oesophageus) in the diaphragm ( hiatal hernia ).

function

The transport of the chunk of food through the esophagus is the last phase of the act of swallowing . It occurs reflexively through the contraction of the striated and smooth muscles: if food gets into the throat , it irritates sensitive nerve fibers. In the brain, the sensory fibers are switched to the motor nuclei of the vagus nerve, which causes the circular muscles to contract. Since the innervation occurs reflexively, the section in which the lump of food is currently located contracts. The muscles directly below relax.

The transport process takes about ten seconds, and several peristaltic waves can be observed: The first wave (primary peristalsis) drives the chunk of food (bolus) down the esophagus. The subsequent waves (secondary peristalsis) are triggered by remaining food particles.

Once the food has reached the stomach, the pressure of the sphincter rises to double the resting value. This prevents the stomach contents from getting back (anti-reflux mechanism). The tension of the sphincters is controlled by the vagus, signaling molecules such as cholecystokinin , somatostatin , glucagon and prostaglandin E1 relax the closure. Also coffee , nicotine and fats can loosen the closure of the lower esophageal sphincter.

Diseases

Depending on the disease, diseases of the esophagus manifest themselves as swallowing disorders ( dysphagia ) , pain when swallowing (odynophagia) , regurgitation , bad breath , heartburn, and chest pain. The last symptom also occurs with heart disease, so we can only speak of "non-cardiac chest pain " if a heart disease (such as a heart attack or circulatory disorder) has been ruled out.

Motility disorders

As a motility disorder , a disorder of involuntary movements is called an organ. In the case of the esophagus, this means impairment of the act of swallowing, which can have different causes.

The achalasia is a rare disease. It is caused by the sinking of the myenteric plexus in the lower esophagus, which on the one hand does not slacken the lower esophageal sphincter sufficiently during the passage of food and on the other hand the food is not transported efficiently towards the stomach because of the weak peristalsis. These are noticeable difficulties in swallowing. In addition, the food remaining in the esophagus can get back into the throat (regurgitation), which harbors the risk of aspiration , especially at night . A common complication of achalasia is therefore aspiration pneumonia , i.e. pneumonia caused by foreign bodies or stomach acid in the lungs .

Two other motility disorders of unknown cause are diffuse esophageal spasm and hypercontractile esophagus ( nutcracker esophagus ). The function of the lower esophageal sphincter is normal in both diseases. In diffuse esophageal spasm, the peristalsis itself is not disturbed, but non-peristaltic contractions occur when swallowing or spontaneously, which impair the act of swallowing. The hypercontractile esophagus does not have these additional contractions; instead, the peristaltic contractions of the smooth muscles are particularly strong and last a long time. Both diseases cause pain behind the breastbone (retrosternal pain) and difficulty swallowing.

If the cause of a motility disorder does not lie in the esophagus itself, but is the result of an underlying disease, it is called a secondary motility disorder. Such a disease can be a connective tissue disease ( collagenosis ) such as scleroderma , amyloidosis or a polyneuropathy in diabetes mellitus . In muscle diseases such as muscular dystrophies or diseases of the central nervous system , the striated muscles of the upper esophagus are particularly affected by the functional disorder.

Reflux disease

Reflux is the term used for the backflow of stomach contents into the esophagus, which manifests itself as heartburn . If this occurs frequently and impairs the quality of life, one speaks of gastroesophageal reflux disease (English: gastroesophageal reflux disease, GERD for short). GERD can be divided into two forms: If the mucous membrane of the esophagus does not show any changes, it is a non-erosive reflux disease , or NERD for short. If the mucous membrane has become inflamed and shows typical changes, it is referred to as reflux esophagitis . The cause of reflux disease is occlusive insufficiency of the lower esophageal sphincter. In addition to heartburn, advanced reflux diseases can also have difficulty swallowing.

A long-term consequence of reflux esophagitis is the so-called Barrett's esophagus : the process, the squamous converts as an adaptation to the constant chemical irritation in epithelium to which the stomach acid can better resist. Further complications are ulcers and narrowing (stenoses) of the esophagus, chronic hoarseness due to irritation of the vocal cords or bronchial asthma .

inflammation

The inflammation of the esophagus is technically called esophagitis ; it can be caused by chemical and thermal irritation ( burns ), mechanical irritation (foreign bodies stuck), and infections. The most common form is reflux esophagitis caused by irritation with stomach acid. Likewise, the esophagus can become inflamed after chemical burns with acids or alkalis, which occurs in children as an accident and in adults mostly with intent to commit suicide . Infection with a pathogen plays a subordinate role in healthy people; people with limited immune defenses , such as diabetics or HIV- infected people, are mostly affected . The most common pathogen is the yeast Candida albicans , infections with cytomegalovirus , varicella-zoster and herpes simplex viruses also occur. The main symptoms are painful (odynophagia) or painless swallowing difficulties (dysphagia) and retrosternal pain (behind the breastbone).

Eosinophilic esophagitis , which usually affects children and young adults, is a relatively recent clinical picture . The entire esophagus is affected by the infiltration of eosinophilic granulocytes . These inflammatory cells play a role in allergies , which is why eosinophilic esophagitis is also assumed to be an allergic cause.

Esophageal cancer

Esophageal cancer is a rather rare form of cancer with an annual incidence of around 8 new cases per 100,000 population , with men being more frequently affected than women. The mortality rate is high because tumor growth is largely symptom-free and only in advanced stages leads to difficulty swallowing and pain. The therapy of such a far advanced disease is less promising. Squamous cell carcinoma is differentiated from adenocarcinoma on the basis of cell types . Squamous cell carcinoma is favored by alcohol consumption and smoking, while adenocarcinoma is a long-term consequence of Barrett's esophagus and reflux disease. Squamous cell carcinoma used to be the much more common form worldwide. In Western Europe and North America, however, adenocarcinomas now predominate, as the increase in overweight ( obesity ) in the population also increases the number of reflux diseases.

Diverticulum

Diverticula are protrusions of the walls of hollow organs, specifically the esophagus, in which either all wall layers are involved ( real diverticulum or traction diverticulum ) or only the mucous membrane and submucosa, which are pressed through the muscle layer under increased pressure ( false diverticulum or pulsation diverticulum ). The most common true diverticulum is the bifurcation diverticulum on the tracheal fork, around 20% of esophageal diverticula are found there.

False diverticula mainly develop at muscular weak points: the Zenker's diverticulum is the most common diverticulum on the esophagus, it makes up about 70% of the esophageal diverticula. However, it is not a real diverticulum of the esophagus, as it arises in the Killian triangle just above the esophageal mouth on the back wall of the lower pharynx and is thus a hypopharyngeal diverticulum . Below the mouth of the esophagus there is another weak muscle, the Laimer triangle , where Killian-Jamieson diverticula can develop. However, these are much rarer. About every tenth diverticulum is a pulsation diverticulum above the diaphragm ( epiphrenic diverticulum ) .

Food debris often accumulates in diverticula and can cause bad breath and difficulty swallowing. These food residues can be regurgitated , which, especially in the case of Zenker's diverticulum, carries the risk of aspiration due to its proximity to the trachea.

Other diseases

As Mallory-Weiss syndrome be called about four centimeters long longitudinal cracks of the mucosa, with vomiting may occur and sometimes heavy lifting. If severe vomiting leads to a crack in the entire wall, we are talking about Boerhaave syndrome . However, perforations in the esophageal wall usually occur during endoscopic examinations; Boerhaave's syndrome is rare.

In humans, Chagas disease can cause the esophagus to swell (dilate) called a megaesophagus . It is more common in pets, especially dogs.

In horses and cattle, large chunks of food occasionally get stuck in the esophagus ( blockage of the throat ).

For the esophageal varices caused by disorders of the venous blood circulation, see above.

In addition to malignant esophageal cancer, benign tumors (papillomas, fibromas, lipomas, myomas and mixed tumors) can rarely occur.

Investigation options

If the symptoms indicate an illness, imaging methods are used for further diagnosis. The endoscope can be used to inspect the mucous membrane to find inflammation, tissue remodeling (such as Barrett's esophagus), or esophageal varices . The endoscopic examination (mirroring) of the esophagus (esophagoscopy) usually takes place as part of a gastroscopy . An ultrasound probe can be inserted into the esophagus under endoscopic guidance . This procedure, called endosonography , can show vascular malformations and the expansion of tumors in the esophageal wall. Another possibility of tumor diagnosis is computed tomography (CT for short).

The esophageal swallowing method is used for X-ray diagnostics . The patient swallows a barium- containing contrast medium, of which an X-ray image is created during the passage through the esophagus . In this way, diverticula, constrictions, the longitudinal extension of tumors and the course of the swallowing process (and thus also disorders and reflux) can be made visible.

A non-imaging method that is important in the diagnosis of motility disorders is esophageal manometry , i.e. the measurement of the pressure in the esophagus. The transesophageal echocardiography (also: sip Echo ), the ultrasound examination of the back (dorsal) sections of the heart by an ultrasonic probe, which is pushed into the esophagus.

Esophageal surgery

Esophageal surgery is a comparatively young discipline of visceral surgery , which has developed with thoracic surgery since the advent of intubation anesthesia after the Second World War . Nevertheless, for a long time surgical interventions, especially in the chest section of the esophagus, were very risky, which is why carcinomas in this area were not considered to be surgically treatable. Operations on the esophagus have been standardized and safely performed since around the early 1980s.

Attempts to surgically remove esophageal carcinoma ( resection ) were made at the end of the 19th century. Theodor Billroth tried his hand at tumors in the neck area in 1871, but failed. Vincenz Czerny achieved the first successful resection there in 1877. Johann von Mikulicz failed to resect a carcinoma in the chest area in 1886; Wolfgang Denk did not succeed in this operation until 1913 . Franz Torek from Lennox Hill Hospital in New York City is considered to be the father of modern esophageal surgery , as he completely removed a patient's esophagus for the first time in 1913 ( esophagectomy ). The first successful series of esophagectomies without opening the chest (so-called blunt dissection) was achieved by Ulrich Kunath since 1978, and in 1998 also using minimally invasive technology.

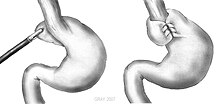

Rudolf Nissen performed the first fundoplication in 1956 , which is still used today to treat reflux disease and hiatal hernias . One procedure similar to the way the lower esophagus works is Hill's posterior gastropexy.

Web links

- Endoscopy atlas on the topic of the esophagus

- Thomas Frieling: Diseases of the esophagus: Many causes, similar symptoms , Pharmazeutische Zeitung , edition 24/2015

literature

- Gerhard Aumüller, Jürgen Engele, Joachim Kirsch, Siegfried Mense; Markus Voll and Karl Wesker (illustrations): Anatomy , online learning program for the preparation course. 3. Edition. Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-136043-4 (= dual series ).

- FW Gierhake: Esophagus. In: FX Sailer, FW Gierhake (ed.): Surgery seen historically: beginning - development - differentiation. Dustri-Verlag, Deisenhofen near Munich 1973, ISBN 3-87185-021-7 , pp. 186-191.

- Herbert Renz-Polster, Steffen Krautzig (Hrsg.): Basic textbook internal medicine . 5th edition. Elsevier, Urban & Fischer, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-437-41114-4 .

- Renate Lüllmann-Rauch: pocket textbook histology . 4th edition. Thieme, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-13-129244-5 .

- Franz-Viktor Salomon, Hans Geyer, Uwe Gille: Anatomy for veterinary medicine . Enke, Stuttgart. 2014, ISBN 978-3-8304-1075-1 .

- Erwin-Josef Speckmann, Jürgen Hescheler, Rüdiger Köhling: Physiology . 6th edition. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-437-41319-3 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Wilhelm Pape , Max Sengebusch (arrangement): Concise dictionary of the Greek language . 3rd edition, 6th impression. Vieweg & Sohn, Braunschweig 1914 ( zeno.org [accessed on September 23, 2019]).

- ↑ Johann Samuelersch, JG Gruber: General encyclopedia of the sciences and arts in alphabetical order by named writers . Ed .: JF Gleditsch. 1824, p. 323 ( google.com ).

- ↑ Pierer's Universal Lexicon of the Past and Present . 4th edition. Publishing house by HA Pierer , Altenburg 1865 ( zeno.org [accessed on September 23, 2019] lexicon entry "Schluckdarm").

- ↑ Gerhard Aumüller et al .: Dual series of anatomy. 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-152862-9 , p. 604 f.

- ↑ a b c d Detlev Drenckhahn (Ed.): Anatomie, Volume 1 . 17th edition. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-437-42342-0 , p. 635.

- ↑ a b Gerhard Aumüller et al .: Dual series anatomy. 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-152862-9 , p. 613 f.

- ↑ Gerhard Aumüller et al .: Dual series of anatomy. 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-152862-9 , p. 605.

- ↑ a b Gerhard Aumüller et al .: Dual series anatomy. 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-152862-9 , p. 606.

- ↑ Stelzner, F., W. Lierse: The angiomuscular expansion occlusion of the terminal esophagus. Langenbeck's Arch. Clin. Chir. 321 (1968) p. 35 ff.

- ↑ Ulrich Kunath: The Biomechanics of the Lower Esophagus , in: Gastroenterologie und Metabolism , Volume 15, Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-13-574501-5 .

- ↑ Michael Schünke u. a .: Prometheus Learning Atlas of Anatomy. Internal organs. 3. Edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-13-139533-7 , p. 162.

- ↑ Michael Schünke u. a .: Prometheus Learning Atlas of Anatomy. Internal organs. 3. Edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-13-139533-7 , p. 164.

- ↑ Detlev Drenckhahn (Ed.): Anatomie. Volume 1. 17th edition. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-437-42342-0 , p. 639.

- ↑ P. Kaufmann et al. The muscle arrangement in the esophagus. Result. Anat. Development-Gesch. 40 (1968) 3.

- ↑ Renate Lüllmann-Rauch: Pocket textbook histology. 4th edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-13-129244-5 , p. 386 f.

- ↑ a b c Renate Lüllmann-Rauch: Pocket textbook histology. 4th edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-13-129244-5 , p. 391.

- ↑ F.-V. Salomon: anatomy for veterinary medicine. 2nd, expanded edition. Enke, Stuttgart. 2008, ISBN 978-3-8304-1075-1 , p. 271.

- ↑ F.-V. Salomon: anatomy for veterinary medicine. 2nd, expanded edition. Enke, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8304-1075-1 , pp. 772-773.

- ↑ Thomas W. Sadler: Medical Embryology. Translated from English by Ulrich Drews. 11th edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-13-446611-9 , pp. 265 and 279.

- ↑ Thomas W. Sadler: Medical Embryology. Translated from English by Ulrich Drews. 11th edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-13-446611-9 , p. 266.

- ↑ Thomas W. Sadler: Medical Embryology. Translated from English by Ulrich Drews. 11th edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-13-446611-9 , p. 280.

- ↑ Erwin-Josef Speckmann, Jürgen Hescheler, Rüdiger Köhling: Physiology. 6th edition. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-437-41319-3 , p. 530 f.

- ↑ Herbert Renz-Polster, Steffen Krautzig (Ed.): Basic textbook internal medicine. 5th edition. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-437-41114-4 , p. 484.

- ^ A b Herbert Renz-Polster, Steffen Krautzig (Ed.): Basic textbook internal medicine. 5th edition. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-437-41114-4 , p. 485.

- ^ A b Herbert Renz-Polster, Steffen Krautzig (Ed.): Basic textbook internal medicine. 5th edition. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-437-41114-4 , p. 486.

- ↑ Gerd Herold and colleagues: Internal Medicine 2013 . Self-published, Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3-9814660-2-7 , p. 434 f.

- ↑ Herbert Renz-Polster, Steffen Krautzig (Ed.): Basic textbook internal medicine. 5th edition. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-437-41114-4 , p. 487 f.

- ↑ Herbert Renz-Polster, Steffen Krautzig (Ed.): Basic textbook internal medicine. 5th edition. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-437-41114-4 , p. 490 f.

- ↑ Gerd Herold and colleagues: Internal Medicine 2013 . Self-published, Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3-9814660-2-7 , p. 440.

- ↑ Werner Böcker et al .: Pathology. 5th edition. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-437-42384-0 , p. 550.

- ↑ Gerd Herold and colleagues: Internal Medicine 2018 . Self-published, Cologne 2018, ISBN 978-3-9814660-7-2 , p. 443.

- ↑ Gerhard Aumüller et al .: Dual series of anatomy. 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-152862-9 , p. 610.

- ↑ a b Gerd Herold and colleagues: Internal medicine 2013 . Self-published, Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3-9814660-2-7 , p. 439.

- ↑ Herbert Renz-Polster, Steffen Krautzig (Ed.): Basic textbook internal medicine. 5th edition. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-437-41114-4 , p. 494.

- ^ Doris Henne-Bruns: Dual series surgery. 4th edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-13-125294-4 , p. 269.

- ↑ Maximilian Reiser, Fritz-Peter Kuhn, Jürgen Debus: Dual series of radiology . 3. Edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-13-125323-1 , pp. 434-436.

- ↑ Maximilian Reiser, Fritz-Peter Kuhn, Jürgen Debus: Dual series of radiology . 3. Edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-13-125323-1 , p. 229.

- ↑ Ulrich Kunath: The surgery of the esophagus. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, New York 1984, ISBN 3-13-655101-X .

- ^ Jörg Siewert, Hubert Stein: Surgery . 9th edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg 2012, ISBN 978-3-642-11330-7 , p. 598.

- ^ LD Hill: Progression in the management of hiatal hernia. Wld.J.Surg.1 (1977) 542.