Fairy tale of the safe man

Fairy tale about the safe man (title of the first edition: Fairy tale about the safe man) is a grotesque verse tale by Eduard Mörike . The opening line reads “Should I tell a fairy tale about the safe man, listen!”.

The story of the giant Suckelborst is told in 292 heximeters. The mischievous young god Lolegrin tempts the inexperienced giant to write a world book in which he is supposed to write down the creation of the world. On behalf of the gods he gives a lecture from his book in front of the shadows of the underworld.

content

Suckelborst, "the sure man", remains in his mother's stomach until the end of the flood, the giant toad, who dies after conception and turns to stone. “The son is not exactly the same as his father Serachadan, a treacherous and cruel forest man, but always a monster, gigantic in shape”. The preoccupation with the safe consists of eating, doing nothing and making evil strokes with which he torments people and animals.

One day he is visited by the young god Lolegrin, the mischievous son of the goddess Weyla, "the mocker of the blessed gods". He insults the safe as "pigskin" and persuades him to proclaim his alleged knowledge of the creation of the world to the dead in the underworld. After initially cursing and raving about the abuse, he reconsidered, steals the barn doors from the farmers in the village and staples them together to make a book. Back in his cave he is overcome by an unimagined, creative intoxication. For a day and a half he scratched his world book “straight and crooked lines, in ineffable languages”.

To proclaim the written wisdom, Suckelborst sets out into the underworld. There he only finds “unpleasant refuse of the lower folk” as an audience. While they listen in amazement to his lecture, the devil secretly sneaks up on them. Behind the back of the safe, he does all sorts of jokes and finally shoves his tail into his coat pocket, "as if he were freezing". The sure "pulls it out by the roots with a quick snap, so that it cracks, a horrible sight!" The devil escapes with wail, the prophetic giant heralds the coming of the golden age, lays the tail as a bookmark in his mighty book and trolls away down.

But Lolegrin, who secretly led him into the underworld and attended his prophetic lecture in the form of a cicada, soars up to the gods to announce the funny prank "and to spice the heavenly meal with sweet laughter".

shape

The poem consists of 292 hexameters. They are not divided into stanzas, but into 16 sections of meaning marked by blank lines. Mörike used the hexameter in the first edition of his poems quite freely. The Germanist Ulrich Hötzer analyzed Goethe's and Mörike's hexameter art and came to the conclusion:

- “Mörike was much more confident and independent [than Goethe] in questions of ancient verse. It is true that he too begins with similarly impartial hexameters and advises his friend Hermann Kurz in a letter of June 19, 1837 to write epic material ... in 'bootless hexameters'. Instead, on July 5, 1837, Kurz sent the, Conversation at the churchyard in Cleversulzbach. In barefoot heximeters'. And next year he praised the first version of the 'Fairy Tale of the Safe Man' for the lax verse that "approaches prose". The 'bootless hexameter' seems to have been almost a principle in those years. But Mörike later (1847) thoroughly revised this work for the second edition of his poems and erased most of the metric nonchalance. "

Emergence

The figure of the safe man was part of the orplid mythology invented by Mörike and his friend Ludwig Amandus Bauer ("Louis"), to which he dedicated the first edition of the fairy tale of the safe man ("To Louis B."). The safe man is first mentioned in writing in a letter from Bauer to Mörike on July 19, 1824:

- "This morning I wrote a letter to my mother ... but at the same time I did not fail to warn her that if the sure man, chased out of your house, should flop down to us, she would not be fooled by him, because lately he has certainly been posing for Herr Möricke. ... If you should have in mind to completely dismiss the belay, just send me his fur, a tanner has to work on it for a whole year. "

In a letter to his friend Ernst Friedrich Kauffmann , which has only partially survived , Mörike sketched key elements of the fairy tale a year later in July 1825:

- "... towards the end of his life [the sure man] had the fixed idea of being a prophet and, arriving in the shadowy world, suddenly stood there with a multitude of raised room doors under his arm, which were stapled together on the hinges with Sailen like a book and which he undoubtedly spent at night in inns etc. w. stole. - But he is of the certain opinion that he is giving lectures from this book. Satan, who once looked into his nose with a nosy eye and made the others laugh, he suddenly tore out the tail and laid it as a sign in cold blood with the words between two open doors (a staging and a hall door). ,So! Do mer morga want to go on. ' Then he closed the book with his foot. trolled seriously. ... "

In the novel Painter Nolten , which Mörike had completed in manuscript in 1830, the fairy Silpelitt met the sure man in the interlude “The Last King of Orplid”, who acted as a good-natured giant towards her. At the end of 1837, Mörike seems to have fixed the safe man 'as a fairy tale in inconsistent verse' and to have completed it in February 1838. In 1846 Mörike came back to the safe man. In the poem "Edible Contemplation" he sang the praises of his shoes, the "honest fellows". He remembered his youth and night walks with his friend:

- "And the conversation overflowed like fire, Until we finally competed in boldness with the sure man, because this primeval world son of the gods in rafting boots rose from the mountains to the sky and with the broad hand of the stars slipped the army into a Habersack."

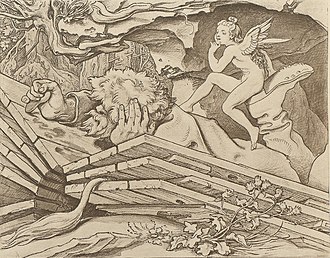

Almost 30 years after the first appearance of the safe man, the painter Moritz von Schwind, who was friends with Mörike, created a drawing of the safe man (see cover picture), for which Mörike thanked Schwind warmly in an enthusiastic letter.

reception

While Mörike's critical friends Friedrich Theodor Vischer and David Friedrich Strauss were uncomprehending about the fairy tale of the safe man, it was particularly valued by the poets Theodor Storm and Paul Heyse and the painter Moritz von Schwind . The poet and literary scholar Friedrich Gundolf admired the mastery with which "Hades and Cleversulzbach, Styx and Neckar were conjured up". While Mörike researchers and interpreters like Martin Stern emphasized the humorous tone of the fairy tale, Romano Guardini saw Suckelborst as a messenger of Christian salvation against the background of Schelling's philosophy.

expenditure

First edition

- Fairy tale of the safe man. In: Eduard Mörike: Poems. Stuttgart: Cotta, 1838, pages 175-189, pdf .

Other issues

- Fairy tale of the safe man. In: Eduard Mörike: Poems. 2nd, increased edition. Stuttgart: Cotta, 1848, pages 87-102, pdf .

- Fairy tale of the safe man. In: Eduard Mörike: Poems. 3rd, increased edition. Stuttgart: Cotta, 1856, pages 90-103, pdf .

- Fairy tale of the safe man. In: Eduard Mörike: Poems. With 1 photograph of the author. Last edition, 4th, increased edition. Stuttgart: Cotta, 1867, pp. 109-124.

Illustrations

- Eduard Mörike: The fairy tale of the safe man , drawings by Christian Bärmann . Munich: H. Schmidt, 1907.

- Moritz von Schwind; Walther Eggert Windegg (editor): Mörike album. Munich: Beck, 1922, plate 2.

- Eduard Mörike: The fairy tale of the safe man. With drawings by Hildegard Weber. Zurich: Fretz, 1924.

- Eduard Mörike: Fairy tale about the safe man. With 18 woodcuts by Hermann Burkhardt. Fellbach: Claudius-Presse, 2003.

literature

General

- Mörike's “fairy tale about the safe man”. In: Arnold Bergstraesser: State and Poetry. Freiburg im Breisgau: Rombach, 1967, pages 231-238.

- The fairy tale of the safe man. In: Romano Guardini: Presence and Mystery. An interpretation of five poems by Eduard Mörike, with some remarks on interpretation. Würzburg: Werkbund-Verlag, 1957, pages 65–97.

- Ulrich Hötzer: “Grata negligentia” - “unbooted hexameter” . Comments on Goethe's and Mörike's hexameters. In: Der Deutschunterricht: Contributions to its practice and scientific foundation, Volume 16, 1964, pages 86-108. - Reprint: # Hötzer 1998 , pages 49-79.

- Fairy tale of the safe man. In: Ulrich Hötzer: Mörike's secret modernity. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1998, pages 165-180.

- B. Lee Jennings: Suckelborst, Wispel and Mörikes Mythopoeia. In: Euphorion: Zeitschrift für Literaturgeschichte, Volume 69, 1975, Issue 3, pages 320–332.

- Fairy tale of the safe man. In: Mathias Mayer: Eduard Mörike. Stuttgart: Reclam, 1998, pages 59-60.

- Mathias Mayer: Fairy tale of the safe man. In: #Wild 2004 , pages 128–129.

- Martin Stern: Mörike's fairy tale about the safe man. In: Euphorion: Zeitschrift für Literaturgeschichte, Volume 60, 1966, pages 193-208.

- Gerhard Storz: Eduard Mörike. Stuttgart: Klett, 1967, pages 204-210.

- Benno von Wiese: Eduard Mörike. Stuttgart: Wunderlich, 1950, pages 137-143.

- Inge Wild (editor); Reiner Wild (editor): Mörike manual: Life - work - effect. Stuttgart: Metzler, 2004.

swell

- Ludwig Amandus Bauer; Bernhard Zeller (editor): Letters to Eduard Mörike. Marbach: German Literature Archive, 1976.

- Eduard Mörike; Hans-Henrik Krummacher (editor): Works and letters: historical-critical complete edition (HKA). Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1967-2008.

Web links

- Bibliotheca Augustana , edition # Mörike 1838 with verse counting.

Footnotes

- ↑ Lolegrin, the youth of the gods, sits on the heel of the giant Suckelborst, the "safe man" who uses coal to label his world book out of barn doors. The devil's tail is stuck in Suckelborst's book as a bookmark.

- ↑ # Mörike 1838 .

- ↑ # Hötzer 1964 , page 87.

- ↑ #Wild 2004 , pp. 211–212.

- ↑ #Bauer 1976 , pp. 22-23.

- ↑ # Mörike HKA 10 , page 102.

- ^ Painter Nolten, Volume 1, 1832, pages 171-173, 197-198.

- ↑ #Mayer 2004 , page 128.

- ↑ # Mörike 1848 , pages 236–238.

- ↑ #Guardini 1957 , pp. 72-74.

- ↑ #Mayer 1998 , page 59.

- ↑ #Star 1966 .

- ↑ #Guardini 1957 .

- ^ Bredt, Ernst Wilhelm (1869-1938): "Christian Bärmann - fairy tales and pictures" . Hugo Schmidt, Munich 1922, DNB 572515790 , p. 9 .

- ↑ Search for “Tale of the Safe Man”.