Mên-an-Tol

Mên-an-Tol ( Cornish for hole stone ) is a 3000 to 4000 year old megalithic formation from the Early to Middle Bronze Age and is located in the county of Cornwall in England . The plant was formerly known as Crick Stone or Devil's Eye .

location

The ancient stone monument is located near Penzance in the former Penwith District between Madron and Morvah . You can get to it on a 1 km long footpath that branches off to the north-east on the road to Madron 2 km after Morvah.

There are other megalithic sites in the area:

- Boskednan stone circle

- Boscawen-ûn

- Chûn Quoit

- Lanyon Quoit

- Merry Maidens

- Mulfra Quoit

- Tregeseal stone circle

- Tregiffian

- Zennor Quoit

construction

The formation consists of three upright granite blocks : a central, ring-shaped and two outer cone-shaped. The stones are three meters apart. Their height is between 1.1 m and 1.5 m. The diameter of the stone ring measures 1.3 m and the opening is 50 cm wide. The megaliths line up pretty exactly along a line from southwest to northeast. Another stone is flat in the ground in front of the southeastern menhir , and two more are a few meters to the west. Other stones could be located under the earth's surface.

A similar formation is formed by two menhirs in Staffordshire in the West Midlands region known as the Devil's Ring and Finger .

Legends and rituals

Mên-an-Tol has produced a wealth of folklore and traditions. For example, a woman who stepped backwards through the hole seven times during the full moon allegedly became pregnant soon afterwards. It was also told earlier that whoever crawled through the hole would be cured of back ailments and body aches. Children should be protected from disease by being passed through the hole in the stone. The facility was also used for divination and for warding off curses.

Research history

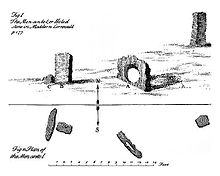

In 1749 the formation was first archaeologically examined by William Borlase , who also prepared the map shown. As can be seen, the megaliths were not in a line as they are today, but formed an angle of about 135 °. The position of the stones must have been changed. The ring stone was probably placed exactly between the other two. Borlase also reported that farmers from the area had already removed some menhirs. The first written records of legends and rituals come from him. He also made initial speculations about how the facility could have been used in prehistoric times, namely for initiation rites and sacrificial acts .

In the middle of the 19th century the local antiquarian John Thomas Blight made several etchings of the stone setting and for the first time expressed the assumption that the megaliths could be the remains of a stone circle. In 1872, William Copeland Borlase , a great-grandson of the elder Borlase, provided a more detailed description of the entire area and reported that stones from numerous dolmens in the area had been used for other purposes. The use for rituals apparently saved the Mên-an-Tol from being transported away.

In 1932, Hugh O'Neill Hencken wrote the first modern scientific presentation of the archaeological site. He assumed that the position of the stones does not correspond to the prehistoric arrangement, but has been significantly changed. In his opinion, the perforated stone was part of a destroyed grave complex. He was also told that local farmers had crawled through the perforated stone with back or limb problems to relieve their pain. This is where the name Crick Stone (contortion stone ) comes from .

In 1993 the Cornwall Historic Environment Service published an extensive memoir containing the latest research. According to this, the cylindrical menhirs originally come from a stone circle from the Bronze Age , which consisted of 18 to 20 stones, of which 11 have so far been located. The stone ring, on the other hand, could be part of a nearby portal tomb from the Neolithic period , because graves were in some cases in the immediate vicinity of stone circles and formed ritual areas with them. However, a stone ring with such a large opening has not yet been proven to be part of a burial chamber. It is conceivable that the perforated stone was in the center of the stone circle and was used to target special points on the horizon. This is countered by the fact that such a use of a perforated brick is not yet known. However, the stone circle of Boscawen-ûn is very close , which has a central stone, so that the central positioning of the perforated stone does not seem completely absurd.

Individual evidence

- ^ William Borlase: Antiquities Historical and Monumental of the County of Cornwall , Bowyer and Nichols, London 1769

- ^ John Thomas Blight: A week at the Land's End , 1861, Churches of West Cornwall , 1864

- ^ William Copeland Borlase: Naenia Cornubiae , Longmans 1872

- ^ Hugh O'Neill Hencken: The Archeology of Cornwall and Scilly , Metheun 1932

- ^ Ann Preston-Jones: The Men-an-Tol. Management and Survey , Historic Environment Service, Cornwall County Council 1993

literature

- John Barnatt: Prehistoric Cornwall: The Ceremonial Monuments . Turnstone Press Limited 1982, ISBN 0855001291 .

- Robin Payne: The Romance of the Stones: Cornwall's Pagan Past . Alexander Associates 1999, ISBN 1899526218 .

- Ian McNeil Cooke: Standing Stones of the Land's End . Cornwall: Men-an-Tol Studio 1998, ISBN 0951237195 .

- Aubrey Burl: The stone circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany . Yale University Press 2000, ISBN 0300083475 .

Web links

Coordinates: 50 ° 9 ′ 31 ″ N , 5 ° 36 ′ 16 ″ W.