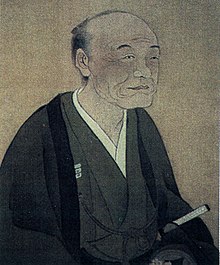

Miura Baien

Miura Baien ( Japanese 三浦 梅園 ), (born September 1, 1723 ( Japanese calendar : Kyohō 8/8/2) in the village of Tominaga ( 富 永 村 ), Bungo Province (today: Tokikiyo, Akimachi, Kunisaki , Ōita Prefecture ); † April 9, 1789 ( Japanese calendar : Kansei 1/3/14) ibid, was a Japanese philosopher of the Edo period , who in a largely secluded life pursued questions of epistemology, natural history, economics, etc. and developed original concepts with Hoashi Banri (1778-1852) and Hirose Tansō (1782-1856) he is one of the Bungo sankenjin ( 豊 後 三 賢人 ), the "Three Wise Men of the Province of Bungo".

Life

Miura Baien alias Yasusada ( 安貞 ) grew up under the name Tatsujirō ( 辰 次郎 ) and Susumu ( 晋 ) as the second son and fifth child of the country doctor Miura Giichi ( 三浦 義 一 ) in a long valley on the Kunisaki peninsula in eastern Kyushu . The name Baien (literally: plum garden), which is common today, was only used later as an author. Since his older brother died early, he took over the medical practice founded by his great-grandfather and worked as a doctor throughout his life.

There was no school in the village, which is why the father provided intensive basic training. Miura's further educational history, however, was modest. At the age of 16 he moved to the Confucian and doctor Ayabe Keisai ( 綾 部 絅 斎 , 1676-1750) in Kitsuki ( 杵 築 ), 15 kilometers away , from whom he was trained for a total of four years. In 1739 and 1743 there was a brief exchange with the Confucian Fujita Keisho ( 藤田 敬 所 , 1698-1776) in the neighboring fiefdom of Nakatsu . But he acquired most of his profound knowledge through self-study. His memoranda, which he kept for more than 40 years, is evidence of the scope and intensity of his reading .

With the exception of two trips to Nagasaki (1745, 1778) and a pilgrimage to the Ise Shrine (1750), Miura remained connected to his home environment throughout his life. Attempts by the feudal lords of Mori, Kurume and Kokura to get him to accept a position as a liege scholar were unsuccessful. Likewise the offer of Matsudaira Sadanobu shortly before Miura's death. In addition to the medical practice, he ran agriculture and taught a small number of his students.

He climbed the mountains around his village until old age. In the summer of 1788 he fell seriously ill for the first time in his life. After a long illness, he died in the spring of the following year, dressed in his best clothes and following the Confucian tradition with his face turned south.

Work and work

Even in his early years he was fascinated by Chinese poetry, which he cultivated into old age. See Miura's six-volume book Shitetsu ( 詩 轍 ), 1786. He also turned to the phenomena of nature early on, with the Daoist classic Huainanzi ( 淮南子 ) from the 2nd century BC. u. Z. began and through Tianjing Huowen ( 天 經 或 問 ) , written by You Yi around 1675, got to know the basics of Aristotelian natural philosophy from cosmology to meteorology, which were imparted by the Jesuits in China .

At the age of 29 or 30, an intensive occupation with the philosophy of Qi (Japanese ki ) becomes clear. A manuscript that was revised and renamed 23 times over the course of time formed the basis of his Gengo ( 玄 語 , "Dark Words") , which he completed in 1775 . In 1755 he began work on a manuscript which, after 15 revisions, was completed in 1789 under the title Zeigo ( 贅 語 , “Superfluous Words”) and which subjected the theories of the past to a critical review. A moral-philosophical text Kango ( 敢 語 , "Resolute Words"), begun in 1760, was already finished in 1763. These three main texts of his work are called "Baiens Three Words" ( Baien sango , 梅園 三 語 ) in Japan .

As we know from his diary ( Kizanroku 帰 山 録 ), on his second trip to Nagasaki he made the acquaintance of some personalities such as Motoki Ryōei ( 本 木 良 永 , 1735–1794), Matsumura Mototsuna, who were renowned for their studies in Holland ( Rangaku ) ( 松 村 元 綱 ) and Yoshio Kōsaku alias Kōgyū. It was through her that he first got to know European scientific thinking. But also in Nakatsu he came across books smuggled into the country, which the Jesuits in Beijing had published in Chinese. Little by little his empiricism became clearer. The heliocentric cosmology of the West captivated him, but also seemed to confuse him. Miura's universe had neither a beginning nor an end. He could not begin with the biblical creation story and the division of the week into seven days, any more than he could begin with the mu of Buddhism . The books, instruments, remedies, etc. in the house of Yoshio Kōsaku, who as the main interpreter of the Dutch trading office Dejima had put together a nationally famous collection, left a deep impression.

Miura showed a keen interest in change in nature. Heaven keep bringing things forth. In contrast to his neo-Confucian contemporaries, who advocated a dualism of the metaphysical principle li and the material force qi , one recognizes a stronger, monistic tendency towards the latter - similar to Kaibara Ekiken . Miura's “original qi ” ( ichi genki ) fills the cosmos, nothing can exist without it. In search of an all-encompassing interpretation of the inner and outer structures of things, he developed a kind of dialectic, based on increasingly complex diagrams, in which opposites are seen as one and are canceled out. His “doctrine of the rational order” ( jōrigaku , 条 理学 ) requires both empirical testing and critical questioning of one's own methods of acquiring knowledge.

Miura's work Kagen ( 価 原 , Origin of Value ), completed in 1773, is an important economic writing in which he investigates the nature and social effects of value. Here we find reflections on the relationship between the amount of money (gold, silver) and the price, on the effects of dwindling food production, on the two sides of high wages, on the emergence of the gap between rich and poor and so on. a. m. One sentence is even reminiscent of Gresham's law : "When bad money (with a reduced precious metal content) circulates widely, good money is hidden". In Miura's view, a stable society requires a minimum of livelihoods, stocks, the containment of superfluous luxuries, fair wages, taxation of the rich, public projects and a good education of children to promote production.

A special enthusiasm for the medical art is not recognizable. Of course, he went into the human body as part of his natural philosophy, but there are no medical researches worth mentioning. Miura was the first to draw attention to the anatomical hanging scrolls of the ophthalmologist Negoro Tōshuku (1698–1755), which he copied in Nakatsu in the house of his son Tōrin and praised it as the forerunner of the body sections initiated by Yamawaki Tōyō in 1754.

Despite his living conditions in a still remote region of the island of Kyushu, Miura was not an unworldly loner. Like his father, helping the rural poor was a matter close to his heart. In 1756 he organized a charity cooperative ( jihi mujinkō , 慈悲 無尽 講 ), which gave its members loans on favorable terms. When Miura's serious illness became known in his later years, they in turn raised money to put his "Dark Words" and "Superfluous Words" into print.

The number of Miura's students was not too large - also because of the remote location of his school. The "school regulations" ( jukusei , 塾 制 ) written in 1766 show that, similar to Hirose Tansō's Kangien Academy, the social status and financial situation played no role, the position of his students was based on their performance. Learning sublimate people. It shouldn't be used for social display. In order to broaden the horizons of his pupils, Miura sent them to other, more advanced institutions if necessary. In addition, dissatisfied students were free to leave school at any time.

Miura's originality found some recognition among contemporaries, regardless of the complexity of his lines of thought. But in 1790, one year after his death, the government issued a "ban on heterodox teachings" ( 寛 政 異 学 の 禁 , Kansei igaku no kin ), which sought to suppress such fruitful, but system-breaking attempts. It is thanks to his descendants that Miura's records have been preserved, but for a long time they were not allowed to ensure that they were distributed further.

Miura Baien today

Miura's house is still today in Aki, together with a small museum, campsite, hotel and observatory as the “home of Baien” ( Baien no sato ). A Miura Baien Society ( Baien Gakkai ) founded in 1975 is dedicated to the difficult exploration of the legacy of this eminent thinker.

Fonts

- Takahashi, Masakazu (ed.): Baien Shiryōshū (Collected Works). Tokyo: Perikansha, 1989 ( 高橋 正 和 編 『梅園 資料 集』 ぺ り か ん 社 )

- Saikusa, Hiroto (ed.): Miura Baienshū (Miura Baien Collection). Tokyo: Iwanami Bunko, 1953 ( 三 枝 博 音 編 『三浦 梅園 集』 岩 波 文庫 )

- Miura Baien: Kagen - From the origin of value - Facsimile of the manuscript created between 1773 and 1789. With comments by Günther Distelrath, Kurt Dopfer, Josef Kreiner , Masamichi Komuro, Hidetomi Tanaka and Kiichiro Yagi. Düsseldorf: Verlag Wirtschaft und Finances, 2001

- Mercer, Rosemary (ed.): Miura Baien, Deep Words - Miura Baien's System of Natural Philosophy. Brill, 1997

literature

- Izuhara, Ritsuko: A Study on the Diagrams by Baien Miura and Sontoku Ninomiya , 2001

- Michel, Wolfgang: Shigai wo miru oro - Tōshuku no Jinshin renkotsu shinkeizu (Looking at Corpses - Negoro Tōshuku's True Shape of Human Bones) . In: Shiryō to jinbutsu (IV). Nakatsu Municipal Museum for History and Folklore, Medical Archive Series, No. 11, 2012, pp. 42-89. ( ミヒェル,ヴォルフガング「屍骸を観る:根来東叔の「人身連骨眞形図」とその位置づけについて」中津市歴史民俗資料館分館医家史料館叢書. )

- Piovesana, Gino K .: Miura Baien, 1723-1789, and His Dialectic & Political Ideas . In: Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 20, No. 3/4 (1965), pp. 389-421

- Ueda, Kanji: Miura Baien no jihimujinkō to fukushishisō (Miura Baien's Charity Association and Welfare Thought). In: Bukkyō Fukushi, No. 4, 1977-11-01, pp. 50–77 ( 上 田 官 治 「三浦 梅園 の 慈悲 無尽 講 と 福祉 思想」。 『佛教 福祉』 )

Web links

- Writings by Miura Baien in the "Database of Pre-Modern Japanese Works" ( National Institute of Japanese Literature )

- Tatsuya Kitabayashi: "Logical Model of Earth Ecosystem" by Baien Miura , 2004

- Ritsuko Izuhara: "A Study on the Diagrams by Baien Miura and Sontoku Ninomiya" , 2001

- Baien no Sato

- Baien Museum (Kunisaki City)

- Demolition of Gengo (Japanese)

- A Study on the Diagrams by Baien Miura and Sontoku Ninomiya, Ritsuko Izuhara , 2001

- Miura Baien: Complete Works, Vol. 1 (digitized from the National Diet Library, Tokyo)

Individual evidence

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Miura, Baien |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | 三浦 梅園 (Japanese) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Japanese Confucian, philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 1, 1723 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Tomikiyo , Bungo Province (today: Tokikiyo, Akimachi, Kunisaki , Ōita Prefecture ), Japan |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 9, 1789 |

| Place of death | Tomikiyo , Bungo Province (today: Tokikiyo, Akimachi, Kunisaki , Ōita Prefecture ), Japan |