Optography

The optography is also called "science to the last image that looks a living from death fixation." Designated.

The idea and the first research approaches with the aim of developing a method that reproduces the last image on the retina of a dead person ( optogram ) date from the 19th century. The name Optogramme comes from the Heidelberg professor Wilhelm Friedrich Kühne .

The scientific significance of optography is minimal due to the lack of usefulness. Historical considerations to use it as a forensic tool could never be realized. Nowadays artists have discovered optography as the magical moment of the last look .

physiology

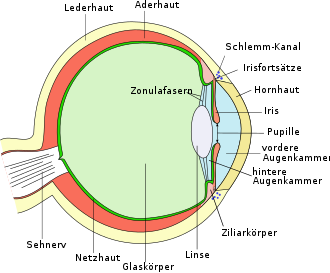

Similar to a camera, an upside-down image of the incident light is created on the retina of the eye . In the retina there are visual cells in which the "visual purple", the rhodopsin , is located. If a photon hits the rhodopsin with sufficient energy, it changes its conformation . Siegfried Seligmann described this effect in 1899 as bleaching the visual purple . So if bright light acts on certain areas of the retina for a long time, these become brighter than the neighboring areas that are not or less exposed. The representation of these retinal changes is called an optogram . Even today, its manufacturing principle is based on the bleaching of the visual purple through bright light.

Historical aspects

The history of optography goes back to the 17th century. At that time, the Jesuit monk Christoph Scheiner saw a picture of a dead frog on its retina and interpreted it as the sight the frog saw shortly before it died.

In 1876 Franz Boll discovered rhodopsin.

A little later Wilhelm Kühne carried out optographic examinations on a rabbit and recognized the image of his laboratory window. Robert Bunsen witnessed the discovery. In 1880 Kühne was able to recognize an optogram on a human retina in the guillotine- executed Erhard Reif . However, it could not be determined what it represented. Later attempts were made to use optograms to solve murder cases . A Viennese newspaper claims to have found out that in one of the sensational mass murder trials of the Weimar era, alongside the Fritz Haarmann and Peter Kürten cases in 1924/25, the Fritz Angerstein case , the chief public prosecutor was the defendant - and probably for the last time in the German Criminal justice history - is said to have confronted this evidence, which appears to be esoteric methods: An optogram would have confirmed the suspect Angerstein as the perpetrator. All attempts to make the process usable for forensic purposes, however, failed, although US judges in the Eborn v. Zimpelman concluded, "Science has found that a perfect 'photograph' of an object reflected in the eye of a dying person remains fixed on the retina after death."

In 1975 the ophthalmologist Evangelos Alexandridis carried out similar experiments again at the Heidelberg University Eye Clinic at the request of criminologists . Optograms could also be successfully created here. However, considerations of a practical implementation of the theoretically possible use in forensics had to be rejected.

Production of an optogram

The first concrete instructions for obtaining optograms go back to Wilhelm Kühne and August Ewald . They carried out their examinations on the eyes of frogs, rabbits and oxen that were still alive or had recently been killed. As essential for the experimental setup, they demanded that the eye must be well fixed, the image must be sharp and the light must be good. At the same time, the exposure time to the light should generally not be less than three minutes.

The production of the optogram itself was described at the end of the 19th century for the rabbit, for example: The eyes were covered immediately after exposure to prevent further light and thus a two-stage change in the retina. The work of opening and hardening the eyes with alum solution was carried out in a dark room . The subsequently detached retina was spread out in a small, concave porcelain dish in such a way that the side originally facing the vitreous was on top. The preparations were preserved by drying with concentrated sulfuric acid .

Evangelos Alexandridis resumed these experiments in the 1970s . He also placed anesthetized rabbits in front of high-contrast images, then killed them, removed the eyes, detached the rear area and also placed them in alum solution (for 24 hours). Then he removed the retina, pulled it onto a small ball the size of an eyeball and let it dry in the dark. Since the preparations were not light-resistant, he photographed them for documentation.

Status

The importance of optography as the magical moment of the last look is more in the realm of art these days. The physiologist Wilhelm Kühne already exhibited his optograms as lithographs .

Reception in the media

In the film Wild Wild West , the main suspect of a murder is determined with the help of optography. In the crime novel "Unterholz" by the Munich author Jörg Maurer , optography is described as a forensic investigation method and a danger for criminals in a seminar for contract killers. In Markus Heitz's thriller "Totenblick" , optography is also used to track down the murderer who "recreates" works of art in real life. In Dario Argento's film Four Flies on Gray Velvet , the method is also used as a possible solution to unmask the murderer.

literature

- Bernd Stiegler: Eye witnesses. Optography in forensics of the 19th and early 20th centuries. In: Amelie Rösinger, Gabriela Signori (ed.): The figure of the eyewitness. History and truth in a cross-disciplinary and cross-epoch comparison. UVK, 2014, ISBN 978-3-86764-515-7 , pp. 135-158.

- Bernd Stiegler: Illuminated eyes. Optograms, or the promise of the retina. S. Fischer Verlag, 2011, ISBN 978-3-10-075550-6 .

- Derek Ogbourne: Encyclopedia of Optography: The Shutter of Death. The Muswell Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9547959-4-8 .

- Derek Ogbourne: The Last Look - Museum of Optography. Catalog for the exhibition in the Kurpfälzisches Museum in Heidelberg with contributions by Frieder Hepp, Kristina Hoge and Stefanie Boos. 2010, ISBN 978-3-938839-89-8 .

- Arthur B. Evans: Optograms and Fiction: Photo in dead Man's Eye. In: Science Fiction Studies. Vol. 20, Part 3, 1993.

- Richard L. Kremer: The Eye as Inscription Device in the 1870s: Optograms, Cameras and the Photochemistry of Vision. In: Brigitte Hoppe (Ed.): Biology integrating scientific fundamentals. Munich 1997, pp. 359-381.

- Georg Popp: Can you see the image of the murderer in the eye of the victim? In: The look around. 29. Vol., No. 5, 1925, pp. 85-87.

- Wilhelm Kühne: Investigations of the Physiological Institute of the University of Heidelberg. Volume 4, 1881, pp. 280ff.

- Wilhelm Kühne: Preliminary communication on optographic experiments. In: Central sheet for the medical sciences. 1877, pp. 33, 49.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b die-stadtredaktion.de: “The last look” - Derek Ogbournes 'Museum of Optography'. (online) ; last accessed on 23 Aug 2010.

- ↑ a b c Kurt F. de Swaaf: The last look. In: Der Spiegel. July 13, 2010, accessed Aug 23, 2010.

- ↑ a b c Derek Ogbourne: The Last Look - Museum of Optography. ( Memento from February 11, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ) Exhibition on optography in the Kurpfälzisches Museum in Heidelberg, viewed on Aug 23, 2010.

- ↑ a b c S. Seligmann: The microscopic examination methods of the eye. S. Karger Verlag, Berlin 1899, pp. 184ff. (Reprint: BiblioBazaar, 2009, ISBN 978-1-110-25650-1 , (online) )

- ↑ a b c d D. Ogbourne: Encyclopedia of Optography. Muswell Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9547959-4-8 , pp. 10ff.

- ↑ Science in Dialogue The Last Look - Museum of Optography. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: www.wissenschaft-im-dialog.de )

- ↑ Instruments of Vision. (= Image Worlds of Knowledge. Art History Yearbook for Image Criticism. Volume 2.2 ). Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-05-004063-7 , p. 25.