Paris – Brest – Paris (cycling race)

Paris – Brest – Paris was a classic cycling race for professionals and amateurs . It was held for the first time on September 6, 1891 and last in 1951. The route ran for about 1200 kilometers from Paris to the city of Brest on the Atlantic and back. In 1931, two cycling marathons, a brevet and an audax , were formed from the amateur class . Both still take place today. Paris – Brest – Paris, along with Bordeaux – Paris, is one of the oldest long-distance road cycling events .

The route to Brittany and back ran largely on the very hilly national road 12. There were around 10,000 meters of altitude to be mastered, which are spread over more than 360 mostly short and not very steep climbs.

story

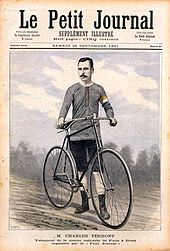

The Paris – Brest – Paris race was launched in 1891 under the direction of Pierre Giffard by the newspaper “ Le Petit Journal ” to demonstrate the durability of the then still young product of the bicycle and as a reaction to the attention given to the one that had previously been held for the first time Bordeaux – Paris race . Since this race was dominated by British racing drivers, Paris – Brest – Paris should be a “French” cycle race: the bicycle is not only useful and healthy, but also an indispensable part of national defense.

206 French men took part, both professionals and amateurs. After three nights without sleep, Charles Terront was the first to cross the finish line with 71:22 hours. He was followed by 97 other cyclists, the last of whom took more than ten days. Due to the enormous logistical effort, the organizers decided to only hold the bike race every ten years.

In the three days up to the arrival of Terront, a similar cycling fever prevailed in France for the first time, as it is later known from the Tour de France .

Separation of the amateur class

At the next edition in 1901, the race was sponsored not only by Le Petit Journal , but also by L'Auto-Vélo magazine (the predecessor of L'Équipe ) under the direction of editor-in-chief Henri Desgrange . The 25 professionals and 114 amateurs competed in their own races. The oldest amateur was 65 years old and it took him a little over 200 hours to complete the route. In addition, there were foreign participants for the first time. In the professional category, the Italian Maurice Garin won after 52:11 hours , who two years later would also win the first edition of the Tour de France . For the first and last time, drivers were allowed to be guided by pacemakers .

The two newspapers had a sophisticated system of relaying news to the editorial offices in Paris, and so many newspapers were sold that Georges Lefebre of L'Auto-Velo suggested that his boss, Henri Desgrange, organize an even bigger race - the Tour de France . This proposal was implemented in 1903, at that time with such big stages that the reference to Paris – Brest – Paris was clearly recognizable.

In 1910, the French pastry chef Louis Durand made from Maisons-Laffitte of the race to his sweet Paris-Brest , inspire the cut ring of choux paste with hazelnut brittle - butter cream filled, is a reminder of a bicycle tire.

At the next Paris – Brest – Paris in 1911, energy-saving driving in groups emerged, whereas in the past people had almost exclusively driven solo. Five drivers stayed together for most of the race. Only shortly before the last checkpoint did Ernest Paul attempt to break out. Ultimately, the pursuer Émile Georget overtook him , who crossed the finish line after 50:13 hours.

In 1921 - just three years after the end of the First World War - only 43 professional drivers and 65 amateurs took part in Paris – Brest – Paris. Among the professionals, the French Eugène Christophe and the Belgian Louis Mottiat fought for victory. In the end, Mottiat won just under 55:07 hours.

With the Australian Hubert Opperman in 1931 a foreigner (49:23 hours) was the first time winner of the professionals. Oppermann broke almost every cycling record before becoming a prominent Australian politician. He had successfully broken out of the field at Paris – Brest – Paris, but was caught up again shortly before Paris. He won his final ride on the velodrome - after only 49:21 hours despite continuous rain. During the race, he ate six kilograms of celery, which he (incorrectly) believed was an important source of energy.

Massive changes in the amateurs

For the amateurs there was a massive change in the regulations in 1931: They no longer started together with the professionals, but as Audax in a closed association. Many amateurs disliked this driving style and so the Audax Club Parisien organized a ride based on the previous driving style, a certification, as a direct competitor to the Audax . There were three different cycling events, each of which was held in the same year.

Due to the Second World War , Paris – Brest – Paris was not held in 1941, as originally planned, but only in 1948. Of the 46 professionals, 11 got back to Paris on time. The winner was Albert Hendrickx, who defeated the Belgian Francois Neuville in a sprint after 41:36 hours.

In 1951, out of 34 professionals, only 11 made it to the finish line on time. The fastest was Maurice Diot with 38:55 hours, who set an unbeaten record to this day. Diot won with a sprint against his breakout colleague Edouard Muller after waiting for Muller to repair a flat tire in Trappes, 22 km from the finish.

Because of the enormous strain and because the amateurs took the strain for a simple bracelet (without the fastest getting a special reward), so few teams registered in 1956 and 1961 that the race was canceled. This marked the end of the Paris-Brest-Paris professional cycling race. The two amateur events will continue to be held.

winner

|

Web links

- Official website

- Paris – Brest – Paris in the Radsportseiten.net database

- TV report from 1951

Individual evidence

- ↑ Benjo Maso : The Sweat of the Gods. The history of cycling . Covadonga Verlag , Bielefeld 2011, ISBN 978-3-936973-60-0 , p. 17 .

- ↑ Benjo Maso: The Sweat of the Gods. The history of cycling . Covadonga Verlag , Bielefeld 2011, ISBN 978-3-936973-60-0 , p. 18 .

- ↑ Benjo Maso: The Sweat of the Gods. The history of cycling . Covadonga Verlag , Bielefeld 2011, ISBN 978-3-936973-60-0 , p. 19 .

- ↑ Illustrated Cycling Express . No. 43/1948 . Express-Verlag, Berlin 1948, p. 343 .