Pteridinium

| Pteridinium | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

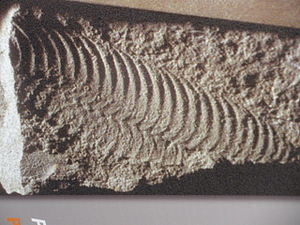

Pteridinium nenoxa (or Onegia nenoxa ) from Russia |

||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||

| Ediacarium | ||||||||

| 558 to 543 million years | ||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||

| Pteridinium | ||||||||

| Gürich , 1933 | ||||||||

| species | ||||||||

|

||||||||

Pteridinium is a fossil of the late Ediacarian , which is countedamong the Erniettomorpha andbelongs toboth the White Sea community and the Nama community .

etymology

Pteridium or pteridinium is derived from the ancient Greek pteron ( Greek τὸ πτερόν , neutr. - 'the wing') in allusion to the wing-shaped shape of the organism.

Research history

The type fossil Pteridinium simplex was scientifically described for the first time by Georg Gürich in 1930 . It appears in the Kliphoek Member of the Nama Group near the Aar farm at Aus . Gürich originally named the fossil Pteridium . Since this name had already been used by Giovanni Antonio Scopoli for the genus bracken in 1777 , it was changed to Pteridinium in 1933 .

Occurrence

Pteridinium is found relatively frequently in deposits of the late Precambrian , particularly in Namibia ( type locality ), in South Australia , in China and on the White Sea in Russia . The fossil also occurs in North Carolina and the Northwest Territories of Canada .

The sites in detail:

- Kliphoek Member of the Nama Group in Namibia (type locality)

- Ediacara Member in the Flinders Range , South Australia

- Shibantan member of the Dengying Formation , Yangtze Kraton , China (at Wuhe near Zigui )

- McManus Formation in Stanly County , North Carolina

- Blueflower formation in the Mackenzie Mountains , northwestern Canada

- Verkhovka formation on the White Sea in Russia

description

Adolf Seilacher (1984) sees pteridinium a genus of Vendobionten who primarily by their quilted acting ( English quilted distinguished) body structure. Similar to an air mattress, the quilted segments could fill with fluid and swell, with the hydrostatic pressure of the body fluid keeping the outer skin of the individual segments taut. Pteridinium is the best example of this blueprint, which is applied to practically all fossils of the Ediacarian. In the case of the vendobionts, a distinction can be made between serially arranged segments and fractally organized segments; another distinguishing feature of the vendobionts is the presence or absence of a stalk. Pteridinium as a pedunculated type is a prime example of the first form of organization (the comparable Swartpuntia is pedunculated).

The body of pteridinium consists of three flag-shaped lobes (English vanes ), which are usually pressed flat, so that usually only two of the lobes are recognizable, the central lobe , which often protrudes into the sediment, is usually covered by the central axis (English seam ). Each lobe is made up of parallel ribs that start with a zigzag seam in the central axis of the three lobes . Often the flag lobes on the side are bent up and then form a boat-shaped, canoe-like structure with a central partition.

Even in very well-preserved fossils, neither the mouth, anus, eyes, legs, antennae nor other processes or organs can be made out. Pteridinium probably grew by adding entirely new sections at both ends. The expansion of existing individual segments, on the other hand, is likely to have made only a minor contribution to growth.

Family position

Pteridinium originally as a primitive cnidarian viewed (Cnidaria), but this seems now as questionable. So interpreted Hans Dieter Pflug (1994) the organism as colonizers and Adolf Seilacher and colleagues (2003) saw him as a giant, single-celled protists with affinity for modern xenophyophore . Retallack (1994) even thought it was related to lichens and Glaessner (1984) interpreted pteridinium as a primitive animal organism.

The relationship to other taxa of the Ediacara biota is still in the dark, transition links are not known. It bears a vague resemblance to Dickinsonia and Spriggina , who share some of Pteridinium's enigmatic characteristics , such as the staggered sliding mirror symmetry of its segments. There are no known descendants of Pteridinium .

Taxonomy

The genus Pteridinium has the following taxa:

- Pteridinium simplex (type fossil)

- Pteridinium nenoxa

- Pteridinium carolinaensis

Habitat

Fossils found in the living position suggest that pteridinium was a shallow sea creature and lay epibiont on the sediment surface covered by microbe mats - roughly comparable to Charniodiscus - partially endobiont in the sediment below the microbe mats - comparable to Ernietta - or fully endobiont in the sediment as an endobenthic organism lived buried. Creep tracks are unknown. It cannot be decided whether pteridinium photosynthesized or was fed by osmosis .

Pteridinium is often associated with disturbed sediment bodies, recognizable by plate structures , landslides and the like. The organism is then bent or folded, and folding back up to 180 ° can be observed. Even criss-crossing adhesions of several individuals are known.

Age

Pteridinium appears in the fossil record for the first time in the Verkhovka Formation in Russia, dated 558 million years ago . As one of the youngest fossils of the Ediacaran biota, the taxon survived until 543 million years BP and thus almost to the end of the Ediacarian. The finds at the type locality in Namibia are somewhat older than 547 million years BP.

Individual evidence

- ^ Gürich, G .: The so far oldest traces of organisms in South Africa . In: International Geological Congress, South Africa, 1929 (XV) . tape 2 , 1930, p. 670-680 .

- ↑ Glaessner, MFW and Glaessner, M .: The late Precambrian fossils from Ediacaran, South Australia . In: Palaeontology . tape 9 , 1966, pp. 599-628 .

- ↑ Chen, Z. et al: New Ediacara fossils preserved in marine limestone and their ecological implications . In: Scientific Reports . tape 4, 4180 , 2014, pp. 1-10 , doi : 10.1038 / srep04180 (2014) .

- ^ Gibson, GG et al .: Ediacaran fossils from the Carolina slate belt, Stanly County, North Carolina . In: Geology . tape 12 , 1984, pp. 387-390 .

- ↑ Narbonne, GM and Aitken, JD: Ediacaran fossils from the Sekwi Brook area, Mackenzie Mountains, northwestern Canada . In: Palaeontology . tape 33 , 1990, pp. 945-980 .

- ↑ Grazhdankin, D .: Patterns of distribution in the Ediacaran biotas: facies versus biogeography and evolution . In: Paleobiology . tape 30 , 2004, pp. 203-221 .

- ↑ Seilacher, A .: Late Precambrian and Early Cambrian metazoa: Preservational or real extinctions? In: Patterns of Change in Earth Evolution . tape 5 , 1984, pp. 159-168 .

- ↑ a b Laflamme, M., Xiao, S. and Kowalewski, M .: Osmotrophy in modular Ediacara organisms . In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . tape 106 (34) , 2009, pp. 14438 , doi : 10.1073 / pnas.0904836106 .

- ↑ Pflug, HD: Role of size increase in Precambrian organismic evolution . In: Neues Jahrb. Geol. Paläontol. Treatises . tape 193 , 1994, pp. 245-286 .

- ↑ Seilacher, A. et al .: Ediacaran biota: the dawn of animal life in the shadow of giant protists . In: Paleontological Research . tape 7 , 2003, p. 43-54 .

- ^ Retallack, GJ: Were the Ediacaran fossils lichens? In: Paleobiology . tape 20 , 1994, p. 523-544 .

- ^ Glaessner, MF: The dawn of Animal Life: A Biohistorical Study . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 1984.

- ^ Glaessner, MF and Daily, B .: The geology and Late Precambrian fauna of the Ediacaran fossil reserve . In: Rec. S. Aust. Mus. tape 13 , 1959, pp. 369-401 .

- ↑ Fedonkin, MA et al .: The Rise of Animals: Evolution and Diversification of the Kingdom Animalia . Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2007.

- ↑ Grazhdankin, D. and Seilacher, A .: Underground vendobionta from Namibia . In: Palaeontology . tape 45 , 2002, p. 57-78 .

- ↑ Narbonne, GM, Saylor, BZ and Grotzinger, JP: The youngest Ediacaran fossils from southern Africa . In: Journal of Paleontology . tape 71 , 1997, pp. 953-967 .

- ^ Schmitz, MD: Appendix 2 - Radiometric ages used in GTS 2012 . Ed .: Gradstein, F. et al., The Geologic Time Scale 2012. Elsevier, Boston 2012, p. 1045-1082 .