Reform time in Hungary

During the reform period in the first half of the 19th century, attempts were made to modernize the Kingdom of Hungary .

Compared to countries like Great Britain or France , the country was less advanced at that time. Numerous social, economic and cultural reforms have been implemented to accelerate development. These primarily concerned the regulation of the question of serfdom and the introduction of modern industry. But poems like the national anthem, which gave expression to national togetherness, were also central. In the interests of the rising bourgeoisie, obstacles opposed to their goals were removed.

Prehistory - the "awakening" of the nation

After the death of Joseph II , the executive power passed into the sphere of influence of the counties, which were under the influence of the aristocracy . The deceased ruler's ordinances were suspended without exception. A euphoria set in in the country, in the course of which its own language, costume, music and dance blossomed. Teaching in Hungarian was prescribed by law in secondary schools and Hungarian armed forces were formed.

Although the nobility supported the ruling Habsburg dynasty in the Napoleonic Wars , it soon became apparent that this collaboration was based only on the prospect of material advantages. After the war, the court devalued the money, closed the National Assembly, and then did not convene it for several years. The first opportunity to address the challenges of modernization was during the Reformed National Assembly from 1825 to 1827.

Great personalities

István Széchenyi

The first phase of the reform period was mainly shaped by the work of Count Széchenyis , whose influence was particularly noticeable in the 1820s and 1830s. He rejected the hedonistic way of life of the nobility and was committed to the economic, technical and social modernization of Hungary. On his travels to England he gained experience for his later work.

In the long term he sought the liberation of the serfs . This was to be done in a slow process in parallel with general progress, but Széchenyi did not make clear how he envisaged the implementation of this plan.

At the first Reformed National Assembly from 1825 to 1827, he presented the concept for an income tax, with the proceeds of which the establishment of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences could be realized.

Against the background of personal experience, he realized that the remnants of feudalism , such as the inalienability of aristocratic property, were obstacles on the way to modernization. In his work Hitel (German: Ueber den Credit ), published in 1830, he worked out a coherent reform program based on a list of these hurdles. József Dessewffy , one of his most important opponents, reacted to the popular book in 1831 with his font A "Hitel" czímű munka taglalatja (German: Zergliederung des Werks : Ueber den Credit ). In the same year a peasant uprising broke out in Upper Hungary ( Felvidék ), which motivated Széchenyi to present his reform program to the public in a short and concise form with the book Stádium . Some of the items on his program were:

- Replacement of serfdom through voluntary payment of inheritance rights

- Extension of the right to purchase land to non-aristocrats

- Repeal of the state's right of reversion

- Equality before the law apply

- Legal protection of parties

- Road construction and regulation of free flowing waters

- Ban on monopolies

- Public Legislation and Trials

- Only laws and contracts that were drawn up in Hungarian should be valid.

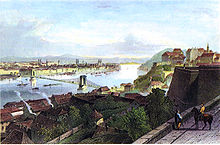

Széchenyi was a forward-looking advocate of reforms, not with his writings, but also with the practical implementation of his theories. For example, he had the Iron Gate made navigable and pushed ahead with preparations for clearing up the Tisza . He also encouraged steam navigation on the Danube, as well as the construction of winter harbors and shipyards. He built the first steam-powered roller mill and made the breeding of silkworms popular. One of his works is the construction of the Chain Bridge . He also tried to expand the rail network of the railway.

In addition to promoting science, industry and transport, I also devoted Széchenyi to private amusements such as horse races and casinos. He also showed himself to be progressive in the private sphere, in that he used the habit of bathing regularly.

Lajos Kossuth

In the 1830s, Lajos Kossuth had a decisive influence on the formation of opinion in the country and shaped the way the public was formed. With the newspaper Országgyűlési Tudósítások , he succeeded in winning over the politically active nobility for the reform ideas.

After his arrest in 1835, he learned the English language and dealt with economics. When the court changed tactics and released Kossuth, he played an even more prominent role. In January 1841 he became editor-in-chief of the daily Pesti Hírlap , which, however, was under censorship. Nevertheless, he managed to discuss the burning political, social and economic problems of the time. He also founded the modern Hungarian press landscape. The newspaper quickly found a wide readership. It initially appeared with a print run of 60 and soon increased to 4,000.

He also made his reform program known by advocating compulsory, state-supported inheritance law on the question of serfdom. Kossuth aimed to subject the nobility to tax liability so that this class would also contribute to bearing the burdens of society. He also stood up for the guarantee of political freedom rights and for a popular representation. He also described his favored form of civil property relations and the realization of political equality. In contrast to Széchenyi's ideas of an aristocratically led change, Kossuth hoped that the middle nobility would push through the reforms.

Kossuth was the leading figure in the revolution against the Habsburg monarchy in 1848/49. Although his newspaper Pesti Hírlap was closed in 1848 in the course of the crackdown on the revolution, he continued his struggle. He founded z. B. a protection association for the Hungarian industry.

Nikolaus Wesselényi

Baron Nikolaus Wesselényi , known as the “boatman of the floods” and “very first Hungarian youth”, was the main figure of the Transylvanian reform period. In addition to his honest and passionate work for the liberation of the serfs, he often stimulated debates in the National Assembly when they reached a dead end.

In his work Balítéletek (" Misjudgments ") he emphasizes that the relationship between the nobility and serfs must be ordered. With another political paper, he wanted to encourage linguists - referring to the national composition of Transylvania - to be more careful.

At the National Assembly of Transylvania in 1837, the opposition recorded a major victory against Vienna : the candidate supported by the Habsburgs was not elected governor .

From 1847 the Hungarian language replaced Latin as the official language in Transylvania. Also in that year the decision of the Transylvanian National Assembly was made on the question of the organization of the crowd , which concerned the division of the land between the nobility and serfs. The Transylvanian serfs could only acquire land under even more unfavorable conditions than was the case in the rest of Hungary, although the land was much smaller. The resulting discontent culminated in the unrest of 1848.

Ferenc Kölcsey

The poet Ferenc Kölcsey also played an important role as a statesman in the reform era. During the National Assembly period from 1832 to 1836, as Ambassador to Sathmar , he attracted attention with his enthusiastic speeches on the question of property rights. The liberals had a solution in mind that would fundamentally and permanently change the status of the serfs. However, this initiative was slowed down by the Conservatives. The representatives of the counties then had to follow the will of the monarchical envoys in their voting behavior. When Kölcsey received such a directive, he withdrew from active political life.

The hymn he wrote became the most important national poetry.

Ferenc Deák

From 1833 Ferenc Deák , the “advocate of the nation” (“nemzet prókátora”), also known as the “wise man of the homeland” (“Haza bölcse”), entered the political stage. With his tactical flair and logical thinking, he took an important position in the reform process. Until his retirement in 1847, he and Kossuth were spiritual leaders of the reformers in the National Assembly.

László Lovassy

The young members of the National Assembly, headed by László Lovassy , were among the closest supporters of the reform ideas . He spread the liberal ideas among the young members of the middle nobility, who mainly pursued legal careers. Since it was necessary to visit the national assemblies as part of the bar exam, they were able to find out firsthand about the reform plans. They soon founded associations in which these ideas were discussed. Their leader Lovassy, like other reformers, was later politically eliminated by the government. He went mad during a 10-year sentence in the Buda Castle Prison. The politicized liberal generation of 1848 emerged from the group of young reformers.

Disputes over the reforms

Dispute between Kossuth and Széchenyi

There were different ideas about how the reform goals would be implemented. The dispute between Kossuth and Széchenyi is indicative of the deep ideological and political differences.

Széchenyi intended to renew the country under aristocratic leadership. The historically given connection between Austria and Hungary seemed to him unchangeable and stifled the Hungarian aspirations for independence in the bud. Notwithstanding this, Kossuth strived for an independent nation state, or at least an economically and politically autonomous status within the Habsburg monarchy.

The two reformers also contradicted each other on the question of social order. Kossuth proclaimed that the nobility alone, without the support of the whole nation, could in no way be able to build a modern civil society.

Széchenyi, who had fallen out of his childhood friend Wesselényi, contradicted Kossuth's views represented in the Pesti Hírlap in the pamphlet Kelet Népe ("People of the East").

The general opinion was closer to Kossuth, while Széchenyi lost approval. He then withdrew from the public eye, and Kossuth replaced him more and more in the role of spiritual leader that Széchenyi had assumed in the 1820s. The reform process took on more radical forms during this period.

National radicalism

The national radicals only played an effective role at the end of the reform period. They did not succeed in gaining direct influence, but over time this group became less and less ignored. Activities that can be traced back to them have only been known since the revolutionary year 1848.

Outstanding representatives of these radicals were the poet Sándor Petőfi , the historian Pál Vasvári and the writer Mihály Táncsics , parents were serfs. The radicals strove for fundamental changes and advocated the liberation of serfs without the binding payment of inheritance rights. In the struggle for their demands, they did not shy away from revolutionary means. Táncsics wrote about the program as follows:

“For landowners, cultivating the fields is the most important and only insurance. Anyone who works on a field can really say that it is his. So the field belongs to us who cultivate it, from which it follows that we do not owe a replacement fee for it. And if you don't want to proclaim this justice in a law, we will enforce it out of necessity. "

Original sound of the quote:

"A földbirtok-tulajdonnak a legfőbb és egyetlen bizonysága a mívelés, ki azt míveli, az mondhatja csak igazán övének. A föld tehát mienk, kik míveljük, következésképpen érte megváltási díjjal igazságosan nem tartozunk. És ha ti nem akarjátok ez igazságot törvényben kimondani, majd a szükségtől kényszerítve mi fogjuk kikiáltani… "

Conservative opponents

The reforms had to be fought from the start against the resistance of the conservative opponents who clung to the feudal structures. In the initial phase, Metternich and Franz I in particular acted as braking forces. From 1835 on, Metternich changed his strategy and switched to violent means to stop the changes. Lovassy, Kossuth, and Wesselényi were jailed.

Later, after the failure of courtly conservatism, Count Aurél Dessewffy organized a party for young aristocrats that wanted to appeal to "level-headed progressives" by the name fontolva haladóknak . By the late 1830s, ultra-conservative viewpoints were no longer widespread. With the increasing success of the reformers, the term backwardness took on a pejorative meaning compared to progressiveness. For tactical reasons, Dessewffy included the term in the name of his party. He also took up some of the reformers' suggestions, albeit only in rudimentary form and misappropriated, in order to get the undecided to his side. In this way he managed to weaken the reformist camp.

Important events

- Bratislava National Assembly 1825-1827 ( 1825-1827-es pozsonyi országgyűlés ): The beginning of the debate over reforms can be linked to this National Assembly, although the direct results were minor.

- Foundation of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences : Count Széchenyi raised an annual income to found it.

- Creation of the Védegylet Protection Association

- Foundation of Pesti Hírlap

- Construction of the chain bridge

Effect and results

At the end of the reform period, Hungary had caught up with Europe and the foundations for a bourgeois Hungary had been laid. The freedom struggle of 1848/49 would not have been possible without the economic strength rooted in this period, national unity and the settlement of the serf question. The prominent role of the nobility in the initiation and reforms and the voluntary relinquishment of their privileges is of particular importance. This did not lead to armed uprisings by serfs as in other countries. Rather, they formed an interest group with the nobility and stood up for the overarching interests of the nation. The real importance of this union was particularly evident during the 1848 revolution. The industry that emerged during the reform period, the prosperity that resulted from it and the broad support of the serfs contributed to the fact that the resistance against the feudal monarchy was more permanent than in other European countries where revolutionary upheavals had occurred. In Hungary, the revolutionaries were only crushed in the course of military support from the Russian tsar.

Movie

- A Hídember

literature

- Történelem . tape III . Nemzeti Tankönyvkiadó, Budapest (Hungarian).

- A romániai magyar nemzeti kisebbség történeleme és hagyományai . Volume I-VII. Stúdium Könyvkiadó, Kolozsvár (Hungarian).

- András Gergely: Egy nemzetet az emberiségnek .

- Zsolt Trócsányi: Wesselényi Miklós és világa .

- György Szabad: Kossuth politikai pályája .

- György Szabad: Magyarság és Európaiság. Kossuth Lajos Európához tartozásunkról . In: Rubicon. Széchenyi és Kossuth . No. 1-2 , 1995.

Web links

- Development of the bourgeoisie, reform and revolution (1790–1849). magyarország.hu, April 5, 2006, archived from the original on August 31, 2009 ; Retrieved February 14, 2009 (Hungarian).

- Géza Alföldy: Hungary and Europe. Heidelberg University, October 19, 2002, archived from the original on December 31, 2002 ; Retrieved February 14, 2009 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Available as an e-book , accessed on February 5, 2011

- ↑ Available as an e-book , accessed on February 5, 2011

- ↑ the area is now part of Slovakia

- ↑ This enabled the serfs to acquire ownership of the land that they cultivated.

- ↑ According to the law of reversion, the property of a noble family falls to the state if there is no descendant who could take over the inheritance. zeno.org

- ↑ from Mihály Táncsics' leaflet Nép szava Isten szava ("Voice of the People, Voice of God")

- ↑ imdb.com