Christianity and Judaism in the Ottoman Empire

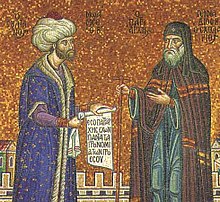

This article looks at the role of Christianity and Judaism in the Ottoman Empire and the privileges and restrictions that result from them. In principle , as required in the Koran , the Ottoman Empire was relatively tolerant of the other Abrahamic religions - Christianity and Judaism - while polytheistic religions were resolutely opposed. With regard to Christianity, apart from regional, temporary exceptions, there was no fundamental policy of planned forced conversion.

Religion as an institution

As a state, the Ottoman Empire constantly tried to balance religious interests by creating appropriate framework conditions. In this context, it recognized the clerical concept and the associated expansion of religion into an institution . As these religious institutions became “legally valid” organizations, the Ottomans then introduced fixed rules into them in the form of ordinances. The Greek Orthodox Church , with which there were peaceful relations, particularly benefited from this . So it was maintained in its structure until the Greek War of Independence (1821-1831) and largely left independent (albeit under strict control and supervision). Other churches benefited less from the institutionalization of religion, such as the Bulgarian Orthodox Church , which like others was dissolved and placed under the jurisdiction of the Greek Orthodox Church.

However, the Ottoman Empire was often a place of refuge for the persecuted and exiled European Jews . Sultan Bayezid II , for example, took the Jews expelled from Spain into his kingdom in 1492 , with the intention of resettling them in the city of Thessaloniki , which was conquered by his troops in 1430 and has since been abandoned .

Nevertheless, the Ottomans' tolerance also knew limits, as the following quotations show:

“[…] One could get the impression that the often received policy of religious tolerance [of the Ottomans] was of an irregular, random nature and was conveniently ignored when changed circumstances suggested a different course […]

[…] one can use the repressive one Regard measures taken against the Greek Church as a departure from normal and established practice - a departure caused by corruption and intrigue by officials and, less often, by outbursts of fanaticism or government resentment. As everywhere, one could expect to find a gap between the established policy and its practical implementation. "

Since the only legally valid Orthodox organization of the Ottoman Empire was the ecumenical patriarchate , the inheritance of family property from father to son was generally considered invalid for Christians .

"Clash of Cultures"

With regard to cultural and religious identities, which have been the most important source of conflict in the world since the end of the Cold War , the Ottoman Empire with its Millet system is often used as an example of fundamentally balancing politics.

The most important question posed by the proponents of the “clash of civilizations” thesis is: “Is it possible to balance conflicts between civilizations?” In fact, at least in Ottoman history there were at least no conflicts between the various religious communities. Tensions with and against the state, including the Armenian rebellions, the Greek Revolution and the Bulgarian National Awakening , have been widely studied, showing that these were based on nationalist rather than religious reasons ( anti-Catholicism , anti-Semitism, etc.). So the entire decline of the Ottoman Empire is a result of the rise of nationalism in the country and not an increase in religious conflicts ( clash of civilizations ). Although the Ottoman Empire tried to curb nationalism through the Tanzimat reforms aimed at equality of religions , through the promotion of Ottomanism and through the first and second constitutional era, it could no longer stop its own decline.

During the entire period of its existence, the Ottoman Empire never pursued a policy that sought to destroy other religions, such as Judaism or Christianity. Rather, the Ottomans always sought a balance between the religions, such as in the ongoing conflict over control of the Holy Sepulcher . Presumably it was only through this tolerant policy that the Christian population on the Balkan Peninsula was able to reconstitute itself as a state during the Balkan Wars . This policy is also evident in dealing with Hagia Sophia , in which after five centuries (1935) the plaster was removed from the mosaics after the young Republic of Turkey "in the interests of art" turned Hagia Sophia into a mosque and a church but had declared it to be a museum. During this transformation, the exterior and interior of the cathedral suffered great damage from the removal of Christian symbols, the plastering of the mosaics and the destruction of the icons .

Interreligious Affairs

The Ottoman Empire had to make decisions not only in Muslim- Christian matters, but also especially in relation to Christian sects. As a result, especially in the period of its decline, it got between the fronts of the struggles for supremacy among Christians. As a result, the Ottoman Empire created laws for religious communities; however, the heyday of the empire was over.

For a long time there was a regulation that allowed schismatic patriarchs to practice the Catholic religion. The Roman Church was also allowed to maintain communication with the Greeks, Armenians, and Syrians as a pretext for teaching these communities. When the empire suffered defeat in the war against Russia and Austria (1737–1739), it tried to get support from France. France, on the other hand, was only willing to provide assistance if the Ottoman Empire explicitly confirmed the law of the French protectorate and at least implicitly guaranteed the freedom of the Catholic apostolate. Accordingly, Sultan Mahmud I declared on May 28, 1740:

“... the bishops and believers of the King of France who live in the kingdom should be protected from persecution, provided they limit themselves to the exercise of their mandate and no one should take part in the exercise of their rites according to the customs in their churches under their control as well as in the other places they inhabit; "

While France smuggled resources into the empire from 1840 onwards in order to expand its influence there, tensions arose between Catholic and Orthodox monks in Palestine in 1847. Sects obtained keys to the temples when they were being repaired. Records of this were given to the Ottoman capital by the protectors, including the French, through the Ottoman governor. The Ottoman governor was later convicted for stationing soldiers inside to protect the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, while actively removing any changes to the keys. Various Christian groups were given priority access to the holy places of Jerusalem for which they were competing by edicts of subsequent governments.

Religion and persecution

The Ottoman legal system followed the idea of a "religious community". Nevertheless, the Ottomans tried to leave the individual largely free to choose their religion. Muslims, Jews and Christians should not impose their beliefs on one another, although there were gray areas between these communities.

It was decreed that people from different millets should wear specific colors, for example on their turbans or shoes. However, this policy was not always followed by all Ottoman citizens.

State-religious law

Modern legal systems claim to be objective and secular . Practice in the Ottoman Empire did not follow this strict attitude until the constitution was introduced in 1878, and was anything but secular. Rather, it assumed that the law should be applied within the religious communities of citizens, thus choosing religious law as the judicial system .

In order to balance central and local authorities, the entire empire was organized in the form of a system of local jurisdiction. Power usually revolved around managing property rights, giving local authorities the space to act on the needs of the local millet. The goal of integrating culturally and religiously different groups then led to the complexity of the judiciary in the empire. It essentially consisted of three court systems: one for Muslims, one for non-Muslims, including Jews and Christians, who ruled over their respective religious communities, and the “trade court”. Cases that did not involve other religious groups, or that did not constitute capital crimes or threats to public order, could bring Dhimmi to their own courts, in which their own legal systems were also followed. In the 18th and 19th centuries, however, dhimmi regularly tried Muslim dishes.

Christians were also liable in non-Christian courts in certain clearly defined cases. Such cases included, for example, a trade dispute or the murder of a Muslim.

Dhimmi visited the Muslim courts, for example, when their appearance was compulsory (e.g. when Muslims brought a case against them) to record their property or business transactions within their own communities. There they initiated negotiations against Muslims, other dhimmi or even against their own family members. The Muslim courts always decided here according to Sharia law.

Oaths sworn by the dhimmi were partly the same as those spoken by Muslims, but partly also tailored to the faith of the dhimmi. Some Christian sources show that Christians were treated according to Sharia law by some authorities. According to some Western sources, "a Christian's testimony in the Muslim court was not considered to be as valid as a Muslim's testimony". Before a Muslim court, Christian witnesses struggled to substantiate their credibility with oaths. For example, it was considered perjury by a Muslim court if a Christian swore a Muslim oath on the Koran (“God is Allah and there is no other god”). It made sense for a Christian to summon Muslim witnesses before a Muslim court, since only they can swear a Muslim oath on the Koran.

Remodeling and destruction of churches

As the ruling institution, the Ottoman Empire also created regulations on how cities should be built and what architecture should look like.

Special restrictions have been placed on the construction, renovation, size and sound of bells in Orthodox churches. For example, an Orthodox church shouldn't be bigger than a mosque. Many large cathedrals were destroyed (e.g. the Apostle Church in Constantinople ), converted into mosques, their inside and outside desecrated (especially the Hagia Sophia, Chora Church , the Arch of Galerius and Hagios Demetrios ) or used as an arsenal for the Janissaries (e.g. St. B. Hagia Irene ).

conversion

Voluntary conversion to Islam was welcomed by the Ottoman authorities because Muslim Ottoman authorities saw Islam as a higher, more progressive and more correct form of belief. Negative attributions towards dhimmi did exist among Ottoman governors - partly because of the “normal” feelings of a predominant group towards inferior groups, partly because Muslims despised those who apparently refused to willingly accept the truth (convert to Islam) even though they did Had the opportunity to do so, partly because of specific prejudices. Initially, however, these negative attributions hardly had an ethnic or racist component. When a Christian became a Muslim, he obeyed the same rules that applied to any other Muslim.

Under Ottoman rule, dhimmi were allowed to “practice their religion under certain conditions and enjoy a lot of communal autonomy,” and at least they were guaranteed their personal safety and the security of their property in return for tribute to Muslims and recognition of Muslims Supremacy. Where conversion was accompanied by privileges, there was no social group or millet that applied a specific policy of conversion to Christian converts with special Muslim law or privileges.

Social status

Recognizing the lower status of dhimmi under Islamic rule, Bernard Lewis , professor emeritus of Middle East Studies at Princeton University , stressed that on most points their position was nevertheless "much easier than that of non-Christians or even heretical Christians in medieval Europe." For example, unlike the groups mentioned in medieval Europe, dhimmi are seldom exposed to martyrdom or exile or forced to change their religion and, with few exceptions, are free to choose their place of residence and occupation.

Lewis and Cohen point out that until relatively modern times, tolerance in dealing with unbelievers, at least according to the Western understanding according to John Locke , was neither assessed nor condemned the lack of faith among Muslims or Christians.

education

In the Ottoman Empire, all millets (Muslims, Jews and Christians) continued to use their training facilities.

The Ottoman Empire set up the Enderun School for training for state functions . Like Murad I in the 17th century, the Ottoman state also used the Devşirme (دوشيرم, Turkish "boy reading"), a strategy that gathered students for the Enderun School, who later occupy higher ranks in the Ottoman army or in the administrative system should by forcibly taking and gathering young Christian boys from their families and bringing them to the capital for training, which was connected with the possibility of a career in the Janissary Corps or for the most talented in the Ottoman administrative apparatus. Most of these collected children came from the Balkan regions of the empire, where the Devşirme system is documented as well as the "blood tax". When the children finally embraced Islam because of the milieu in which they grew up, each of them was considered a free Muslim.

Taxes

Taxes from the perspective of the dhimmi who came under Muslim rule were “a concrete continuation of the taxes they had already paid to previous regimes” (but now lower under Muslim rule) and from the perspective of the Muslim conquerors they were material evidence for submission to the dhimmi.

It has been proven that the Ottoman Empire found itself in a difficult economic situation during its decline and during times of dissolution. The claim that the Muslim millet was economically better off than the Christian millet is highly questionable. The Muslim states that were able to save themselves from the dissolution had no better socio-economic status than the rest. All contradicting claims are therefore highly questionable. That economic incentives have been used for conversions, even if some Western sources claim so, is not a certain fact. It is also questionable that the planning of economic policy was geared towards conversions, as in this statement:

"The difficult economic situation of the Sultan's Christian subjects, as well as the needs of the Ottoman Empire during its expansion , resulted in the introduction of the tithe , which forced many Orthodox farmers to convert to Islam."

The tithe is the exception to the custom of the Janissaries. The claim that there was not a single millet, other than Christian or Muslim, that spoke of a special policy for "Christian-converted Muslim millets" is not supported by any source. Voluntary conversion to Islam was associated with privileges. Conversion from Islam to Christianity, on the other hand, was punishable by death.

Protectorate of the Mission

Ottoman state and religion have another dimension that began with the surrender of the Ottoman Empire , namely the treaties between the Ottoman Empire and European powers to secure religious rights in the Ottoman Empire. The Russians became official protectors of the Eastern Orthodox groups in 1774, the French for the Catholics, and the British for the Jews and other groups. Russia and England competed for influence over the Armenians and both perceived the Americans and their Protestant churches, which had established over 100 missions in Anatolia during World War I , as a weakening of their own Eastern Orthodox teaching.

literature

- G. Georgiades Arnakis: The Greek Church of Constantinople and the Ottoman Empire. In: The Journal of Modern History. Vol. 24, No. 3, 1952, ISSN 0022-2801 , pp. 235-250.

- Lauren Benton: Law and Colonial Cultures. Legal Regimes in World History, 1400-1900. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2001, ISBN 0-521-00926-X .

- Claude Cahen: Jizya. In: Clifford E. Bosworth (Ed.): The Encyclopedia Of Islam. Brill, Leiden 2004.

- Amnon Cohen: A World Within. Jewish Life As Reflected in Muslim Court Documents from the Sijill of Jerusalem (XVIth century). 2 volumes (Vol. 1: Texts. Vol. 2: Facsimiles. ). Center for Judaic Studies - University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia PA 1994, ISBN 0-9602686-8-5 (Vol. 1), ISBN 0-935135-00-6 (Vol. 2).

- Richard J. Crampton: A Concise History of Bulgaria. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2005, ISBN 0-521-61637-9 .

- Elie Elhadj: The Islamic Shield. Arab Resistance to Democratic and Religious Reforms. Brown Walker Press, Boca Raton FL 2006, ISBN 1-59942-411-8 .

- John L. Esposito: Islam. The straight path. 3. Edition. Oxford University Press, New York NY 1998, ISBN 0-19-511234-2 .

- Ernest Jackh: The Rising Crescent. Turkey yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Goemaere Press, sl 2007, ISBN 978-1-4067-4978-6 .

- Tore Kjeilen: Devsirme. . In: Encyclopaedia of the Orient. (As of August 7, 2009).

- SJ Kuruvilla: Arab Nationalism and Christianity in the Levant. (PDF, 278 kB) [o. J.]. (this online resource is no longer available).

- Ranall Lesaffer: Peace Treaties and International Law in European History. From the late Middle Ages to World War One. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2004, ISBN 0-521-10378-9 .

- Bernard Lewis : The Arabs in History. Reissued. Oxford University Press, Oxford et al. 2002, ISBN 0-19-280310-7 .

- Bernard Lewis: The Jews of Islam. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1984, ISBN 0-691-00807-8 .

- Philip Mansel : Constantinople. City of the World's Desire. 1453-1924. John Murray Publishers Ltd, London 2008, ISBN 978-0-7195-6880-0 .

- Don Peretz: The Middle East Today. 6th edition. Praeger, Westport CT et al.1994, ISBN 0-275-94576-6 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Arnakis (1952): 235. - Excerpt . Original quote: "one may be led into thinking that [the Ottomans'] much-spoken-of policy of religious toleration was of an erratic, haphazard nature and was conveniently ignored when new circumstances seems to suggest a different course of action" [...] [...] one may regard the recurrent oppressive measures taken against the Greek church as a deviation from generally established practice - a deviation that was occasioned by the corruption and intrigue of officials and less frequently by outbursts of fanaticism or by imperial disfavor. As elsewhere, here, too, one might expect to find a gap between established policy and its practical application. "

- ↑ Jackh (2007): 75 miles.

- ↑ Original quote:… “The bishops and religious subjects of the King of France living in the Empire shall be protected from persecution provided that they confine themselves to the exercise of their office, and no one may prevent them from practicing their rite according to their customs in the churches of their possession, as well as in the other places they inhabit; and, when our tributary subjects and the French hold for purposes of selling, buying, and other business, no one may bother them for this sake in violation of the sacred laws. "

- ↑ Kuruvilla [o. J.].

- ↑ Mansel (2008): 20-21.

- ↑ a b c Benton (2001): 109-110.

- ↑ Al-Qattan (1999): page number is missing .

- ↑ Crampton (2005): 31.

- ↑ Lewis (1984): 32-33.

- ^ Lewis (1984): 10, 20.

- ↑ Lewis (1984): 26. - Original quote: "was very much easier than that of non-Christians or even of heretical Christians in medieval Europe"

- ↑ Lewis (1984): 62; Cohen (1994): XVII.

- ^ Lewis (1999): 131.

- ↑ Lewis (1995): 211; Cohen (1994): XIX.

- ↑ Kjeilen: Devsirme.

- ↑ a b Cahen (2004): page number is missing .

- ↑ Esposito (1998): no page number .

- ↑ Elhadj (2006): 49.