Rum rebellion

The Rum Rebellion (German: Rum Rebellion ) of 1808, also called Rum Puncheon Rebellion (German Rumfass Rebellion ), was the only successful armed uprising against a government in the history of Australia . The governor of New South Wales , William Bligh , was appointed by the New South Wales Corps under the command of Major George Johnston , together with John Macarthur, on January 26, 1808, the 20th anniversary of Arthur Phillip's European settlement in Australia. Thereafter, the colony was ruled by the senior military officer, who was stationed in Sydney as Lieutenant Governor , until the arrival of the British Major General Lachlan Macquarie , who took up his service as the new Governor in 1810.

The term Rum Rebellion was coined by the English Quaker named William Howitt , who is now questioned by historians, as the rebellion came about through other causes, through a power struggle between government and private interests.

Appointment as governor

William Bligh , best known for his removal as captain in the mutiny on the Bounty , was a naval officer and the fourth governor of New South Wales . He succeeded Governor Philip Gidley King in 1805 when he was offered the position by Sir Joseph Banks . It is possible that he was chosen by the British government because of a reputation for being a tough man. He had a good chance of pacifying the rebellious New South Wales Corps that its predecessors were unable to do. Bligh left England for Sydney with his daughter, Mary Putland, and her husband, who died suddenly in January 1808 in the run-up to the Rum Rebellion. Bligh's wife had stayed in England.

Even before his arrival, his leadership style created problems with subordinates. The Admiralty gave command of the ship convoy to the Porpoise and the low-ranking captain Joseph Short, while William Bligh commanded a transport ship. This led to skirmishes that resulted in Captain Joseph Short firing over the ship's bow at Bligh to force him to heed his signals. When this failed, Short tried to order Lieutenant Putland, Bligh's son-in-law, to assist him with the fire on Bligh's ship. However, Bligh went on board the Porpoise and took control of the entire ship convoy.

When they reached Sydney, Bligh removed Short from his captaincy, supported by the testimony of two officers on board the Porpoise . Bligh transferred command to his son-in-law Putland and also deprived Short of the rights to 2.4 square kilometers of land as payment for the trip. Short was sent back to England after arriving in Sydney and tried before the court-martial, which, however, acquitted him of the charge.

The President of the Court, Sir Isaac Coffin, wrote to the Admiralty making verifiable statements against Bligh that included influencing officers to issue false endorsements against Short. Bligh's wife obtained a statement from one of the officers who denied these statements. Sir Joseph Banks and other Bligh supporters worked successfully against the deposition of Bligh as governor.

Arrival in Sydney

Shortly after his arrival in Sydney in August 1806, Bligh passed on greetings to Major George Johnston as representative of the military, to Richard Atkins as representative of the civil administration and to John Macarthur as representative of the free settlers. Shortly afterwards he received greetings from the free settlers from Sydney and the Hawkesbury River region with a total of 369 signatures - some only as a cross - with the explanation that Macarthur did not represent them, that they criticized him for his sheep keeping, as well as for the price development of mutton.

The farmers reported that their land had been flooded by the Hawkesbury River, which was a major economic problem for the colony. One of Bligh's first steps was to allocate supplies to those most in need. In addition, rules for lending were developed that took into account the solvency of their businesses. This earned Bligh the gratitude of the farmers, but also the enmity of the Corps traders, who would have liked to enrich themselves from the plight of the farmers.

Bligh, who was subject to the instructions of the Colonial Office , tried to normalize trading conditions in the colony by prohibiting bartering through the use of spirits as a means of payment. In 1807, Bligh suggested to the Colonial Office that, despite the expected opposition, the practice of bartering spirits as a means of payment should be stopped. Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh , of the Colonial Office replied to Bligh that he had received his instructions on December 31, 1807. The instructions would stop the bartering of spirits and HV Evatt concluded in his history of rebellion that “ … Bligh was authorized to prevent free importation, to preserve the trade under his entire control, to enforce all penalties against illegal import, and to establish regulations at his discretion for the sale of spirits ”(German:“ ... Bligh was authorized to restrict the import of alcohol, to protect the trade and to bring it completely under his control, to exhaust all penalties against illegal imports and to restrict the trade in alcoholic beverages at his own discretion regulate. ”According to Evatt, these measures weakened the monopoly in the colony and, by limiting the trade of the wealthy, served the welfare of the poor settlers. Bligh ended the previous exercise of promising large lands to the already wealthy and influential colonists. During his stay in New South Wales he was granted about 16 square kilometers of land, half for himself and half for his daughter.

Bligh turned other colonists against him. At first he did not intervene against the revolt of a group of Irish accused, but when six of these convicts were released and eight charged, he arrested all of them. Without further explanation, Bligh removed the chief surgeon of D'Arcy Wentworth Colony from his position; he sentenced three traders to one month in prison and described this in a letter as a deliberate offensive. Bligh also dismissed Thomas Jamison , the influential physician-general of New South Wales, he described as unsuitable for managerial administrative tasks: Jamison, in addition to his official duties, had increasingly dedicated himself to maritime trade, he was a friend and business partner of Macarthur. Jamison did not forget that Bligh had fired him because of his trade and supported the later impeachment of Bligh.

In October 1807, Major George Johnston complained in writing to the Commander in Chief of the British Army that Bligh had insulted and obstructed troops of the New South Wales Corps. It is clear that Bligh had made enemies of most of the colony's influential figures. He had also opposed numerous people when he ordered that, since they had leased land from the Sydney government, they should leave their homes on the lease.

Enmity between Bligh and Macarthur

John Macarthur arrived in Australia with the New South Wales Corps in 1790 as a lieutenant, and by 1805 he pursued agricultural and commercial interests in the colony. He was recognized as a successful pioneer in Australian sheep farming. He had arguments with the governors before Bligh and had fought three duels: Duffy sees this behavior in his biography of Macarthur as the key to his character and his excessive desire for recognition.

The interests of Bligh and Macarthur clashed in a number of areas. Bligh stopped Macarthur from distributing cheap and large quantities of wine to the Corps. He also stopped Macarthur's illegal import of distilleries . Macarthur's interest in a land that Governor King had granted him conflicted with Bligh's interests in town planning. Macarthur and Bligh had other disagreements, which included a conflict for a ship landing place. In June 1807 a convict escaped and left Sydney on one of Macarthur's ships, and in December 1807, when that ship returned to Sydney, the Macarthur navigation permit was deemed to be inadequate and forfeited.

Bligh had hired attorney Richard Atkins to issue a December 15, 1807 revocation of Macarthur's shipping permit. Macarthur disregarded this order and was arrested, but was released when he assured his appearance at the next session before the criminal court in Sydney on January 25, 1808. The court sat down with Atkins and six Corps officers.

Macarthur objected to Atkins' participation in the trial against him because he was his debtor and his relentless enemy. Atkin refused, but the Macarthur protest resulted in the support of the other six members of the court, all officers of the corps. Without the lawyer, the trial could not continue and the court was dissolved.

Bligh accused the six officers of mutiny and called in Major George Johnston to negotiate the matter with him. Johnston replied that he was unable to attend because his ship sank on the evening of January 24th on the way home to Annandale after a meal with the Corps officers.

Impeachment of Bligh

On the morning of January 26, 1808, Bligh again ordered the arrest of Macarthur and the return of the court documents that were now in the hands of the Corps. The Corps responded by requesting a new lawyer and bailing Macarthur. Bligh summoned the officers to the Government House in Sydney to legally answer the matter and informed Major Johnston that he believed the conduct of the Corps officers to be treasonous.

Instead, Johnston went to jail and ordered Macarthur to be released. A petition was drawn up asking Johnston to arrest and prosecute Bligh by the colony. The petition was signed by the officers of the corps and other prominent citizens. But, according to Evatt's report, most of the signatories asked for only Bligh to be placed under house arrest. Johnston then consulted the officers and instead issued the order that Bligh "charged by the respectable inhabitants of crimes that render you unfit to exercise the supreme authority another moment in this colony; and in that charge all officers under my command have joined." Johnston went to Bligh and appealed for him to resign and put himself under arrest.

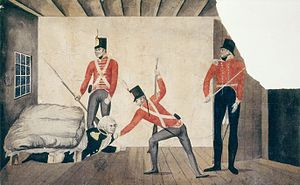

At six in the afternoon the Corps marched to Government House to arrest Bligh. They were prevented from doing so by Bligh's daughter and her parasol. But Captain Thomas Laycock eventually found Bligh in full uniform behind his bed, hiding behind paper.

Bligh has been portrayed as a coward, but Duffy corrects that Bligh was hiding in an attempt to thwart the escalation and coup. In his book Captain Bligh's Other Mutiny , Stephen Dando-Collins agrees and goes so far that Bligh intended to travel to Hawkesbury and lead the garrison there against Johnston. During 1808, Bligh was held at Government House. He refused to go to England without first being legally discharged from his duties.

Johnston appointed Charles Grimes, a general expert, a lawyer and found Macarthur and the six officers innocent. Macarthur was appointed Colonial Secretary and began handling the colony's business affairs.

Another prominent opponent of Bligh, Thomas Jamison, was appointed the colony's naval officer (comparable to a customs revenue manager and instructor). Jamison was reassigned to administration, which enabled him and the Corps officers to examine Bligh's personal records for evidence of errors in his impeachment. In June 1809 Jamison sailed for London to support his business interests and to gather counter-evidence for the prosecution of Bligh that might be brought against the mutineers.

Jamison died in London in early 1811 and had no opportunity to testify in the upcoming court martial that began in June 1811.

Appointment of a new governor

On Bligh's fall, Johnston succeeded as governor on the instructions of his superior officer, Colonel William Paterson , who had established the Tasmanian settlement at Port Dalrymple (now Launceston ). Paterson had reluctantly followed the clear orders that had reached him from England. When he realized that Lieutenant Governor Joseph Foveaux was returning to Sydney in March with orders from England to become the Lieutenant Governor, Paterson left Foveaux to negotiate the current situation.

Foveaux arrived in July and took over the colony, which angered Macarthur. Since that decision, which was expected by England and marked by the impression that Bligh's behavior was unchangeable, Foveaux placed Bligh under house arrest and devoted his attention to the improvement of roads, bridges and public buildings in the colony that had been criminally neglected. When there was no word from England about his measures, he summoned Paterson to Sydney in January 1809 to clarify the matter.

Paterson sent Johnston and Macarthur to trial in England and limited Bligh's stay in barracks until he signed the contract on his return to England. Paterson, whose health was deteriorating, returned to the government building in Parramatta and left the colony to Foveaux.

In January 1808, Bligh was given control of the HMS Porpoise on the condition that he return to England. However, Bligh sailed to Hobart in Tasmania and sought the support of Lieutenant Governor David Collins to regain control of the colony. Collins did not support him and, on Paterson's orders, Bligh was to leave the ship Porpoise and dock in Hobart by January 1810.

The Colonial Office ultimately decided that sending out naval military governors was unsustainable. The New South Wales Corps, now called the 102nd Regiment of Foot (infantry), was ordered back to England and replaced by the 73rd Regiment of Foot (infantry), whose commanding officer was placed under the governor's command. Bligh was appointed governor for twenty-four hours and was ordered back to England. Johnston was also tried in England and Macarthur in Sydney. Maj. Gen. Lachlan Macquarie ordered Maj. Gen. Miles Nightingall to hand over his mission; he fell ill before he abdicated. Macquarie took over the governorship, which was given to him in a solemn ceremony on January 1, 1810.

Aftermath

Governor Macquarie reinstated all officials who had been sacked by Johnston and Macarthur, and canceled land and property transfers that had been made since Bligh was impeached. Although calm had returned, he made pledges of support and prevented revenge. When Bligh got the news of Macquarie's arrival, he sailed from Hobart for Sydney, which he arrived on January 17, 1810, to gather evidence for the court-martial against Major George Johnston. He sailed for the court martial for England on May 12th and reached it on October 25th, 1810 on board the Hindostan .

Government officials in England had heard information from both sides and were not impressed by Macarthur and Johnston's statements against Bligh, or by Bligh's ill-tempered letters accusing key figures in the colony of unacceptable behavior. Johnston was convicted, found guilty, and deposed under martial law; the lowest penalty possible. He was then able to return to his estate in Annaddale, Sydney, as a free citizen. Macarthur was not convicted, but was denied permission to return to New South Wales until 1817 because he did not admit his wrongdoing.

Bligh's appointment as admiral was withheld from Johnston until the end of the court martial. He was then appointed retrospectively to July 31, 1810 and was given a position he wished for. He pursued a career as a naval officer in the Admiralty in an unspectacular manner and died in 1817.

Macquarie was impressed with the quality of Joseph Foveaux as an administrator. He wanted to use Foveaux as the successor to Collins as lieutenant governor of Tasmania because he assumed that a collaboration with Bligh is not possible. However, Foveaux returned to England in 1810 as he was being summoned to court martial to testify about Bligh's arrest and arrest, so Macquarie's request was ignored. Foveaux returned to active service in 1811 and was given a command for a light regiment, and he then pursued an uneventful military career that promoted him to the rank of lieutenant general.

Causes of the Rum Rebellion

Michael Duffy, a journalist, wrote in 2006:

“The Rum Rebellion has slipped into historical oblivion because it is widely misunderstood. It is popular belief that the autocratic Bligh was removed because he threatened the huge profits that were being made from trading in spirits by the officers of the NSW Corps and by businessmen such as John Macarthur. This view suggests it was nothing more than a squabble between equally unsavory parties. The conflict had greater depth than that of a mere squabble, however. Essentially it was the culmination of a long-running tussle for power between the government and private entrepreneurs, a fight over the future and the nature of the colony. The early governors wanted to keep NSW as a large-scale open prison, with a primitive economy based on yeomen ex-convicts and run by government fiat. "

“The Rum Rebellion has been historically forgotten because it was completely misunderstood. Indeed, it is widely believed that the authoritarian Bligh was ousted because his intervention jeopardized the huge profits that New South Wales Corps officers and businessmen like John Macarthur were making in the liquor trade. Accordingly, only two equally unpleasant interest groups got in each other's way. The argument went deeper than a mere bickering, however. At its core, a long-term power struggle between the government and entrepreneurs came to a head, a struggle for the future and the essence of the colony. The first governors wanted New South Wales to have the status of a large-scale prison, the primitive economic life of which would be run by released former convicts and directed according to the wishes of the government. "

Duffy believes this riot was about more than rum:

“... almost no one at the time of the rebellion thought it was about rum. Bligh tried briefly to give it that spin, to smear his opponents, but there was no evidence for it and he moved on. Many years later, in 1855, an English Quaker named William Howitt published a popular history of Australia. Like many teetotallers, he was keen to blame alcohol for all the problems in the world. Howitt took Bligh's side and invented the phrase Rum Rebellion, and it has stuck ever since. "

“... hardly anyone thought at the time of the rebellion that it was about rum. Bligh briefly tried to portray the dispute in such a way as to damage his opponents, but for lack of evidence he dropped it. Many years later, in 1855, an English Quaker named William Howitt published a popular story of Australia. Like many abstainers, he endeavored to identify alcohol as the cause of all the ills in the world. Howitt took Bligh's side and invented the term "rum rebellion" that has stuck to events ever since.) "

Some historians doubt that Bligh's economic policies sparked the uprising: after all, Bligh's removal would not have changed the line of the Colonial Office that a new governor would simply follow. Rather, Bligh had socially reset the lower nobility in New South Wales and thereby turned them against themselves. Duffy, in his story of early Australia, portrays Macarthur's complaints as ridiculous and agrees with Evatt that Macarthur was legally guilty on two of the three counts raised against him, including as the ringleader of a riot. Both state that Bligh acted legally and within the scope of the powers granted to him. Arresting people and threatening the court to do the same if wrongly judged can be seen as a legal issue against authority. Duffy states: If Johnston had been called up on January 25th, the Rum Rebellion would never have happened.

Rum rebellion in literature

The Rum Rebellion is also reflected in literature. In the four-part children's book novel Abby-Lynn-Saga by Rainer M. Schröder , the hero Melvin Chandler is one of the honest traders and merchants who are trying to legalize the rum trade.

literature

- Duffy, Michael: Man of Honor: John Macarthur , Sydney, Macmillan Australia, 2003.

- HV Evatt: Rum Rebellion: A Study Of The Overthrow Of Governor Bligh By John Macarthur And The New South Wales , 1943.

- Tom Frame: Who'll watch guardians when ex-officers rule us? , The Australian, January 23, 2008

- Fitzgerald, Ross and Hearn, Mark: Bligh, Macarthur and the Rum Rebellion , Kenthurst: Kangaroo Press, 1988.

- Ritchie, John: The Wentworths: Father and Son , Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1997.

- James Spigelman : Coup that paved the way for our attention to rule of law . In: Opinion . Sydney Morning Herald. January 23, 2008. Retrieved January 23, 2008. (Spigelman is Attorney General of New South Wales.)

Individual evidence

- ^ First Australian political cartoon fuels Rum Rebellion folklore (PDF) In: Media Releases . State Library of New South Wales. 2008. Archived from the original on February 29, 2008. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved February 4, 2008: “When an unknown artist created Australia's first political cartoon, little did he know his drawing would seep into the country's folklore and shape the perceptions on Governor Bligh's dramatic arrest and overthrow, 200 years ago on Australia Day. This cartoon [was] created within hours of the mutiny and ridicul [es] Bligh. The colored work depicts the hunted Governor being dragged from underneath a bed by the red-coated members of the NSW Corps, later referred to as the Rum Corps. "It was very unlikely that Bligh would have hidden under the bed, the image was political propaganda, intending to portray Bligh as a coward." The slur on Bligh's character created by the cartoon was extremely powerful. The work was first illuminated by candles and displayed prominently in the window of Sergeant Major Whittle'j house. Throughout the years the image continued to blur the reality about the true events of the rebellion. "

- ↑ Duffy, pp. 248-249.

- ↑ a b Ritchie, p. 102

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k A. W. Jose et al. (Ed.): The Australian encyclopaedia . tape 1 . Angus & Robertson, Sydney 1927, p. 171-172 .

- ↑ a b Rex Rienits (Ed.): Australia's Heritage . tape 1 . Paul Hamlyn, Sydney 1970, p. 254-257 .

- ↑ Evatt, pp. 88-89

- ↑ a b c d e f g Michael Duffy: Proof of history's rum deal In: Sydney Morning Herald . January 28, 2006.

- ↑ a b Ritchie, pp. 106-110

- ^ A b John Macarthur (1767-1834), pioneer and founder of the wool industry . In: The Biography of Early Australia . Retrieved August 6, 2006.

- ^ The Australian Encyclopaedia. Volume 1, p. 686.

- ^ Duffy: pp. 4-7.

- ↑ a b c d e f Series 40: Correspondence, being mainly letters received by Banks from William Bligh, 1805-1811 . In: Papers of Sir Joseph Banks: Section 7 - Governors of New South Wales . State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on February 16, 2006. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved March 26, 2006.

- ↑ a b c d A. W. Jose et al. (Ed.): The Australian encyclopaedia . tape 2 . Angus & Robertson, Sydney 1926, p. 3-4 .

- ↑ Stephen Dando-Collins: Captain Bligh's Other Mutiny . 2007.

- ↑ Vivienne Parsons: Australian Dictionary of Biography . National Center of Biography, Australian National University, Canberra 1967, Jamison, Thomas (1753-1811) - ( adb.anu.edu.au ).

- ↑ a b A. W. Jose et al. (Ed.): The Australian encyclopaedia . tape 2 . Angus & Robertson, Sydney 1926, p. 278-279 .

- ↑ a b A. W. Jose et al. (Ed.): The Australian encyclopaedia . tape 2 . Angus & Robertson, Sydney 1927, p. 485-486 .

- ^ The Australian Encyclopaedia. Volume 2, p. 15.

- ^ The Australian Encyclopaedia. Volume 2, p. 196.