South African nationality

The South African citizenship determines the membership of the state association of the Republic of South Africa with the associated rights and obligations. Since 1994 citizenship has been accompanied by uniform civil rights.

As usual in British tradition, there has long been a strong place of birth ( ius soli ) component . Through various changes, the principle of descent has been strengthened more and more.

Historical development

The Cape Colony and the province of Natal had been British since the end of the Napoleonic Wars . The almost deserted areas in the northeast, not yet populated by Bantus in the early 18th century , were made arable by settlers of Dutch origin who had migrated from the Cape and fled the British . Different Boer republics emerged . Their burghers were white descendants of the Dutch who came with the VOC . Well-organized states existed with the Transvaal Republic and the Orange Free State .

In the Cape Colony and Natal British nationality rules applied. However, the Immigration Acts of 1902 and 1906 ensured on entry that certain undesirable persons were not allowed to stay: they required sufficient travel money, integrity (no mentally ill, criminal or prostitute) and reading and writing skills in a European language.

In the Transvaal z. B. White men born here became burghers when they came of age at 21, or had lived here for a year and bought property, or who became citizens directly for £ 7 10d. bought. This status was associated with the right to own land for men who had to be Protestants, which in turn ensured eligibility. On the other hand, the men from 16 to 60 (effectively 18-50) were required to serve in the militia, and horses and weapons had to be provided by themselves. Later a distinction was made between burghers 1st and 2nd class. The former must have lived in the republic before 1876 and participated as a militiaman in one of the campaigns of the 1880s / 1990s. Second class citizens were naturalized and their male descendants aged 16 and over. After twelve years, the House of Lords decided to give them 1st class civil rights. Foreign children born in the country could register at the age of 16, then they became second class citizens at 18. She was able to upgrade the House of Lords after ten years. A fee of £ 2 was payable in each case for naturalizations.

Act. 3 of 1885 banned the naturalization of non-Europeans, with the exception of British subjects from India, who were notifiable and taxable.

The Boers, if they lived in the territories , became British subjects through the annexations after the Second Boer War ; Refugees returning from 1902 as soon as they swore the oath of loyalty provided for in the peace treaty.

After the end of independence, from 1904, foreigners could be naturalized after five years in the Transvaal. A year in the colony and four years elsewhere in the Empire was enough. The Orange River Colony adopted these provisions.

South African Union

Important constitutional changes were brought about in 1910 by the establishment of the internally self-governing South African Union , which through the Westminster Statute in 1931 remained part of the Empire, but was de jure an equal partner of the mother country. After a referendum in 1960 , the Commonwealth left the Commonwealth in 1961, which lasted until 1964. It was renamed "Republic of South Africa."

Through the Naturalization of Aliens Act, No. 4 1910 (Union) and Immigrants Regulation Act, No. 22 of 1913, the rules of the Cape Colony were adopted practically unchanged for the whole, newly created Union.

The British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914 determined for the first time more precisely the previously more customarily defined (theoretically uniform worldwide) status of the British subject (“British subject”). Even this law allowed (only) the self-governing Dominions to differentiate between different classes of British subjects, which helped legitimize the discrimination against Indian migrant workers in South Africa, which has been common since the 1890s. In principle, the nationality of a married woman followed that of the man until 1948.

Later, the British Nationality Act 1948 was issued which regulated the status of (remaining) colonial subjects. For the self-ruled South Africa it was only important until 1961 with regard to the increasingly meaningless status of a “Commonwealth citizen” and for residents from other British colonies.

Nationality Act 1926

For the first time a "Union citizenship" was created with the British Nationality in the Union and Naturalization and Status of Aliens Act, 1926. It stipulated that everyone born in the Union was its citizen, unless he had a foreign citizenship. Furthermore, this applied to every British subject, if legally entered the country, after at least two years of main residence ( domicile ) here. Foreign nationals who had lived legally for three years in one of the four parts of the Union and who had become British subjects , regardless of the law , also became citizens of the Union. “Prohibited immigrants” in the sense of the foreigner legislation remained excluded.

Anyone who had lived in the Empire for five of the last eight years could now be naturalized. The last year prior to the application must have been spent in South Africa. Women marrying in acquired citizenship at the wedding. Furthermore, children born abroad to a South African father.

With the abandonment of the domicile , citizenship of the Union was lost. It could be abandoned if the person concerned was entitled to another citizenship in the Commonwealth , but this did not affect the status of British subject .

- Other laws

- Aliens Act, 1937

- Naturalization and Status of Aliens Amendment Act, 1942 (№ 35 of 1942, in effect May 9) directed against potentially hostile aliens and their wives

Definitions of the “Union Nationals” can be found in:

- Union Nationality and Flags Act, Act № 40 of 1927, which de facto incorporated Southwest into the Union under constitutional law

- Nationalization and Amnesty Act, Act № 14 of 1932

Nationality Act 1949

The South African Citizenship Act of September 2nd, 1949 applied to all “persons born in the Union or South-West Africa” without racial discrimination. This is the first time that there is talk of a “South African nationality”.

All citizens of the Union who had this status due to older laws or were born in South West Africa after the Citizenship Act came into force in 1926, provided they lived in the country and did not have any other citizenship (acquired), were defined as South Africans. Also included were people who had been excluded under the provisions of the 1942 Act and “British Subjects” who were legally living in the country due to older rules. An administrative procedure to determine existing citizenship, corresponding naturalization registers and certificates was planned. Incorrect information was punishable by punishment in accordance with the statutory provisions on perjury (“perjury”).

Marriages no longer had an impact on citizenship issues. Women who had lost their Union citizenship through marriage due to older laws were again considered to be South African citizens or British subjects when it came into force.

- Acquisition

For the period after the entry into force there was a strong ius soli component, so that all native-born South Africans became South Africans provided their parents or mother were legally in the country. There were restrictions on the children of interned hostile foreigners and people who were illegally (as “prohibited person”) in the country. Children of foreign fathers in the South African civil service also became citizens from birth.

In the case of foreign births, South African citizenship was only passed on through the father. Since 1983, foreign births had to be registered in the correct form.

The provisions on acquisition by registration were repealed in 1962. These had primarily affected people who had become “British subjects” through the annexation of the Boer republics or those who fell under the amnesty of 1932.

- Naturalization Requirements

- Of legal age

- good character

- legal residence in the country with permanent residence permit

- four years of residence within the last eight, including the year prior to the application without interruption. (Government service abroad or on ships with a South African flag were also included. Exclusion periods were stays in prison, madhouse, internment or prisoner-of-war camp, etc.)

- The waiting period for descendants in the male line of former "burghers" of the Boer republics or former South African citizens could be waived

- for foreign wives and widows there was a shortened period of two years

- Knowledge of one of the official languages, English or Afrikaans (for speakers of both, the waiting period could be reduced to three years.)

- Citizenship knowledge and the desire to live in the country permanently

Naturalizations were purely a discretionary decision of the interior minister. The naturalization certificate was only issued if a naturalized person (over 14 years of age) took the appropriate oath of allegiance within six months of the positive decision.

Reasons for revocation were, at the discretion of the Minister:

- Incorrect information in the application

- Convictions:

- to a sentence of more than one year or a fine of over £ 100 within five years of naturalization

- for treason, lese majesty, “sedition,” breach of the peace

- acting abroad disloyal to his majesty (until 1962)

- Further ministerial reasons, particularly those relating to minors, were repealed by Law No. 95 of 1981. In these cases, the person concerned had the option of a hearing before a three-person commission headed by a judge from the Supreme Court.

- Amendment of the law in 1984

Foreign nationals with no previous convictions who would have been entitled to permanent residence and who had lived in the country for five years after 1978 were granted naturalization rights if they were between 15½ and 25 years old. This naturalization took place automatically and was intended, above all, to secure young conscripts for the increasingly oppressed regime. If they did not want to, minors had to make a statement to the contrary before the effect occurred . On the other hand, the minister had the right to exclude “certain groups of people” (meaning blacks and Asians) from applying this rule.

- Reasons for loss

- for adults, in the event of a stay abroad and voluntary acceptance of foreign citizenship (except in the case of marriage) automatically or submission of a corresponding declaration (i.e. dismissal), which could be refused in the event of war. The same extended to children. (With regard to the requirements and formalities, changed as of May 13, 1963.)

- Children expatriated with one of their parents could request re-naturalization within one year of reaching the age of majority.

- as a dual national when joining a foreign armed forces while at war with South Africa.

- People who became South Africans through naturalization or registration lost them again after spending seven years abroad, unless they were in the South African civil service or had ministerial permission.

- South Africans born and living abroad lost their citizenship even if they did not have a valid passport.

- Other laws

The age of majority was 21.

Other laws affecting citizenship issues:

- Commonwealth Relations Act, № 69 of 1962

- Residence in the Republic Regulation Act, № 23 of 1964

- Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act 1959 and Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act, 1970 (= National States Citizenship Act, 1970), repealed Apr. 27, 1994

- Matters concerning Admission to and Residence in the Republic Amendment Act, № 53 of 1986 (= Residence in the Republic Amendment Act, 1986)

- Restoration of South African Citizenship Act, № 73 of 1986 (repealed January 1, 1994 by Restoration and Extension of South African Citizenship Act, № 96 of 1993).

- Attainment of Independence by Namibia Regulation Act, 1990 and Application of Certain Laws to Namibia Abolition Act, № 112 of 1990

Nationality Act 1995

The Interim Constitution, in effect Apr. 27, 1994, established equal rights for all citizens. The 1996 constitution guarantees the right to citizenship. It also contains a prohibition on disenfranchisement. The age of majority was lowered to 18 in 2005. Marriage without a marriage certificate (“customary union”) and polygamy is recognized, as has gay marriage since 2006.

South African Citizenship Act, 1995 (SACA). Responsibility lies with the Department of Home Affairs. Birth certificates, South African identity cards or the administrative procedure "Determination of Citizenship Status South Africa" are used as evidence. Incorrect information can be punished with up to eight years in prison.

Immediately after the decree, there was an amnesty for undocumented workers, mainly from Mozambique . Especially in the first years after the end of apartheid, when the South African economic power had not yet been destroyed by corruption and mismanagement by the ANC government, there was illegal immigration from neighboring countries. Since 2005 there have been repeated xenophobic pogroms by native blacks against the immigrants. For this reason, too, the ministry's interpretation of the provisions has been increasingly strict since 2005. In addition, there is incompetence, the excuse that there are no “regulations” or the globally popular argument of “national security” is used to disadvantage applicants. All that remains for them is the expensive and usually unaffordable march through the courts, which takes 4–5 years without support.

- From birth

or descent (foreign birth ”by descent”) South African is:

- who became a citizen under previous laws or by descent

- who was born in the national territory since the law came into force (limited 2010)

- who was born out of wedlock to a South African in civil service

- who was born abroad with a South African parent, if the birth was properly registered.

- who according to Adopted by a South African under the Child Care Act, 1983

- Children of stateless persons can acquire citizenship from birth, provided the birth has been registered.

Children of foreigners who do not have the right of permanent residence in South Africa became citizens from birth if at least one parent was legally in the country.

This was tightened in 2010/3 so that they can only apply for South African citizenship when they come of age if they have lived here continuously and have a corresponding birth certificate.

Certain verification difficulties result from the formal requirements of the Births and Deaths Registration Act. So z. B. illegitimate children can only be registered under the mother. Registration is not allowed at all without a regulated residence status.

- Naturalization Requirements

hardly changed compared to the older rules:

- Of legal age

- good character

- Residence requirement: the waiting period required four years of ordinary residence in the country during the last eight years prior to application. For married or widows it was shortened to two years of marriage and residence in South Africa.

- Knowledge of one of the official languages

- Citizenship knowledge and the desire to live in the country permanently

An oath of allegiance must be taken before the naturalization certificate is issued. Naturalization can be revoked in the event of fraud or false information.

- Dual statehood

Dual statehood is possible, especially if a foreign citizenship ex lege, e.g. B. was acquired through marriage, birth abroad in an ius soli state or similar. Minors who have received another citizenship (with their parents) also remain South Africans for life.

Anyone who, as an adult, voluntarily wants to take on foreign citizenship must, as was already provided for in the 1949 law, obtain a letter of retention from the Minister of the Interior beforehand . This rule has been applied more strictly since 2011. It is particularly important for the large number of South Africans who have emigrated to Great Britain and who, if they have even one former British grandparent, are accepted under easier conditions.

- Reasons for loss

- automatically upon voluntary acceptance of foreign citizenship or submission of a corresponding declaration (i.e. dismissal)

- by ministerial order:

- as a dual national when joining a foreign armed forces waging a war against South Africa. (Since 2010: "waging a war that South Africa does not support.")

- until 2004: use of a foreign passport

- Withdrawal is possible if a South African has been sentenced to more than twelve months in prison, even abroad, provided that statelessness does not occur.

Marriages no longer have an impact on citizenship issues.

- Acceptance

People who have lost their South African citizenship can apply for it again (“certificate of the resumption”), possibly also as dual citizens.

In any case, South Africans who were citizens from birth retain the right to permanent residence for life.

Amendment to the law in 2010

The previous category “citizenship by decent” was put on an equal footing with “at birth”.

The previous acquisition through ius soli for children born in South Africa with a foreign parent has been tightened to the effect that they only become South African citizens if they have lived in the country until they reach the age of majority.

A ruling by the Constitutional Court at the end of February 2020 restored the ius soli , which was abolished in 2013, for children of foreigners born in South Africa without the right of permanent residence, so that they can now obtain citizenship upon application when they are of legal age.

The waiting period for naturalization applications has been changed to five years of permanent residence prior to the application, whereby stays abroad over 90 days are not permitted during this period. Since 2002 a permanent residence permit has only been issued after five years of legal residence with a different status, so that the waiting period has effectively been extended to ten years. This now also applies to spouses. Also new is the required proof of giving up foreign citizenship if the home country does not allow dual citizenship. The measure is aimed primarily against citizens of the development community in southern Africa .

The minister can, at his own discretion, approve naturalizations for highly qualified people after a shorter waiting period, but has to submit a list of names to parliament.

International agreements

South Africa has not acceded to either the Statelessness Convention or the Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness .

South Africa ratified the Refugee Convention and its Additional Protocol in 1996 , but did not sign the more extensive African Refugee Convention . In the light of the experience of the first generation of ANC leaders, a refugee law that was far-reaching by African standards was passed. Recognized refugees (theoretically) have the option of obtaining a permanent residence permit as a prerequisite for later naturalization. Since a legal reform in early 2020, when around 191,000 asylum seekers were registered, regulations have been applied in a very petty way. You don't shy away from refoulement either.

According to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which one has acceded, one would have to ensure that all children were given a nationality, but this is bound to legal residence and strict formal requirements for registering at the registry office. This effectively prevents a large number of foreign children from obtaining citizenship. South Africa has not acceded to the even more far-reaching migrant workers convention until 2020 .

The above explains why the Nationality Act lacks any protective measures or alleviations. There is also no provision of any kind regarding the presumption of birthplace of foundlings.

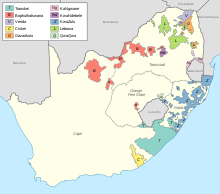

Homelands

Existing reserves were gradually converted into homelands (= Bantustans) for various Bantu tribes from 1959 onwards . Here the indigenous population had political participation rights within the narrow framework of the time. By the Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act, 1970, each black population of South Africa was national ( citizen ) of homelands , but stopped (yet) citizens ( national ) of South Africa. Starting with the Transkei in 1976 also were Bophuthatswana in 1977, Venda in 1979 and 1981, the Ciskei independent, but this was not recognized internationally.

These areas then enacted at the same time as their constitutions, e.g. B. the Transkei Constitution Act , nationality laws that hardly differ in content. The respective nationality was given, described here using Bophutatswana as an example, who:

- was born as a black man in the homeland, if at least one parent was a citizen (including mixed race), regardless of place of residence.

- Blacks who had their main residence (“domicile”) there for five years before independence or who had applied for naturalization after the waiting period.

- Blacks who used one of the Bantu languages typical of their tribe when they were not from another homeland. This also included people of other races (Indians, so-called “colored,” whites or Asians) if they used the respective Bantu language as their mother tongue.

- Relatives of the foregoing when identified with the homeland's way of life and culture. This concerned z. B. non-blacks marrying in, even if they lived elsewhere.

The establishment of commissions called “citizenship boards” was planned to resolve cases of doubt. The Homelands issued appropriate certificates and passport-like documents (the word “passport” was missing on the envelope). They were not internationally recognized. Within South Africa, such people were considered "non-citizen nationals."

Through the Restoration of South African Citizenship Act, 1986 those homeland citizens who were born before the respective independence and lived permanently in the Union became South Africans again. Under the Restoration and Extension of South African Citizenship Act , all Bantustan citizens became South African citizens again, effective Jan. 1, 1994.

South West Africa

For the German Reich, its colonies remained abroad under constitutional law. With increasing expansion, this could hardly be justified from 1905 onwards. The colonial administration of German South West Africa already did everything possible to deny colored residents access to rights. The group of Baster , Boer-African mixed race, who immigrated in 1895 were considered to be natives. In 1903 3,700 whites lived in the country; before the beginning of the war there were 15,000, including almost 13,000 Germans, of which 3,058 women and 3,042 children. One effect of the new German Citizenship Act of 1913 (RuStaG) was that natives who joined the Schutztruppe, only 1,819 men in 1914, no longer automatically became Germans.

Deutsch-Südwest was conquered by South African troops commanded by Jan Smuts until March 1915 . German civilians were interned under much better conditions than in India . The Versailles Treaty placed the area under the administration of the South African Union as a C mandate called South West Africa. Unlike in other English colonies, the Boer-dominated government had an interest in keeping German farmers in the country. 7,855 Germans, around two thirds of the pre-war number, were allowed to stay; this corresponded to 55% of the white residents in 1920. In the next few years the question of their citizenship arose acutely. According to British imperial law, colored Mandate residents were to be seen as stateless “protected persons”, which was not a problem with regard to the non-whites (“natives”), whose number was around eight times larger. The German government demanded a certain amount of self-government for the “ Southwest .” Since the end of martial law in 1921, the Union had been planning to naturalize the resident Germans by law as “British subjects,” but not Union citizens. After negotiations with the Mandate Commission of the League of Nations in 1923, the compromise arose that Germans who did not want to be naturalized would be given a six-month option . About 300 men made use of this, which then extended to women and children. §25 from RuStAG resulted for en bloc addition, the parallel property of the kingdom affiliation -Eingebürgerten. The Weimar Republic also agreed to the London Agreement in October 1923, whereby it achieved that naturalized citizens of the Southwest should be legally equated with Union citizens. Furthermore, an agreement was reached on exemption from military service for thirty years as well as guarantees for German as an official and school language, etc.

The regulation of the Naturalization Act drafted in 1924 read: “Notwithstanding anything contained in the Naturalization of Aliens Act, 1910, as so applied to the Territory, every adult European who, being a subject of any of the late enemy powers, was on the first day of January, 1924, or at any time thereafter before the commencement of this Act, domiciled in the Territory shall, at the expiry of six months after the commencement of this Act, be deemed to have become a British subject naturalized under the said Act of 1910, unless within that six months he signs a declaration that he is not desirous of becoming so naturalized. "

From 1926 onwards, the incorporation of the Boer Dorsland trekkers and another group of Boers, who had fled the British occupation of their republics and therefore did not become British subjects in 1902 when they were annexed due to lack of residence in the occupied territory, was legally problematic . The German governor had issued a settlement permit in 1905. As a result, the Naturalization of Aliens in the Mandated Territory of South West Africa Act, № 27 of 1928, was issued.

People of German origin were interned again during World War II, the citizenship granted in 1924 was revoked in 1942, but restored by the Nationality Act 1949.

From 1962 onwards, the country began to “South Africanize”. The withdrawal of UN trusteeship that followed in 1966 had no effect on citizenship until independence in 1990.

After 1990 see main article: Namibian citizenship

literature

- Hobden, Christine; Report on Citizenship Law: South Africa; Badia Fiesolana 2018 (CADMUS)

- Hobden, Christine; Shrinking South Africa: Hidden Agendas in South African Citizenship Practic; South African Journal of Political Studies, Vol. 47 (2020), No. 2

- Jessurun d'Oliveira, Hans Ulrich [* 1933]; Nationality and apartheid: some reflections on the use of nationality law as a weapon against violation of fundamental rights; San Domenico 1989 (EUI working papers)

- Klaaren, Jonathan; From prohibited immigrants to citizens: the origins of citizenship and nationality in South Africa; Cape Town 2017 (UTC Press); ISBN 9781775822288

- Special issue: Paper Regimes, Kronos magazine , No. 40 (Oct. 2014)

- Manby, Bronwen; Statelessness in Southern Africa ; Briefing paper for UNHCR Regional Conference on Statelessness in Southern Africa Mbombela (Nelspruit), South Africa 1-3 November 2011

- Olivier, WH; Bophutatswana Nationality; South African Yearbook of International Law, Vol. 3 (1977), pp. 108-18

- Steinberg, Kurt; The question of citizenship in South West Africa since the Treaty of Versailles; Archives of International Law, Vol. 4, pp. 456–89

Individual evidence

- ↑ The Aliens Naturalization Act, No. 2 of 1883 (Cape), amended by No. 35 of 1889, mainly contained provisions on residence rights. The model was the Immigration Restriction Act, № 1 of 1897 (Natal), amended in 1903. Here it was stipulated that in addition to the Europeans born in Natal, all natives were also “British subjects”. This also applied to Indians and Chinese, as long as they were not subject to the exclusion conditions of older laws.

- ↑ Act № 30 of 1906 repealed the previous law completely. It is expressly mentioned in § 3 that Yiddish is a European language.

- ↑ Law No. 1, 1876 of June 12th. Whoever came afterwards had to take an oath of allegiance.

- ↑ Statesman's Yearbook; London 1900 (Macmillan), p. 1120.

- ↑ " Coolies , Arabs, Malays and Mohammedan subjects of the Turkish Dominion ." Amended by a resolution of the Volksraads, Art. 1489 (12 Aug 1886) and Art. 128 (16 May 1890). Similar restrictions applied in the Orange Free State from 1891. [Klaaren (2017), p. 21ff.] In addition, there was the obligation to register and purchase a passport subject to charges, which was extended to the Chinese after the Boer War ( Chinese Exclusion Act, No. 27 of 1904, defused 1906, repealed by Act 19 of 1933) .

- ↑ The racial restriction of 1885 remained.

- ↑ 1909 [Union of South Africa] Act.

- ↑ Together with the new constitution: Republic of South Africa Constitution Act, № 32 of 1961.

- ↑ 4 & 5 Geo. c.17, in force Jan. 1, 1915.

- ↑ 11 & 12 Geo. 6 c. 56, in force Jan. 1, 1949. (Canada 1921 and 1946, Australia and New Zealand only passed their own citizenship laws in 1947/8, India , Pakistan and Burma became independent in these years and followed with their own laws in 1950/1.)

- ↑ Act № 18 of 1926, amended by № 4 of 1927.

- ↑ № 49 of 1949, consolidated version with changes up to 1991 . Amendment Acts South African Citizenship Amendment Act: 1961, 1973, 1978, 1980, 1981, 1984.

- ↑ Which restored the rights of those involved in the 1922 strike in Witwatersrand, the so-called "Rand rebellion," which was suppressed by armed violence.

- ↑ The fighting took place in South Angola, in South West Africa and against fighters of the African National Congress infiltrating from Zambia and Zimbabwe .

- ^ Full text: Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1993 .

- ↑ № 88 of 1995. Full text . In addition Department of Home Affairs; Regulations on the South African Citizenship Act, 1995, № 1122, Dec. 28. 2012.

- ↑ Cf. Ngwane, Trevor; Bond, Patrick; South Africa's Shrinking Sovereignty: Economic Crises, Ecological Damage, Sub-Imperialism and Social Resistances; Vestnik Rossiĭskogo universiteta druzhby narodov. Serii͡a︡ Mezhdunarodnye otnosheni͡a, Vol. 20 (2020), No. 1, pp. 67-83.

- ↑ The registration requirement was deleted from the law in 2013, but not from the associated “regulations”. The case of Chisuse and Others versus Department of Home Affairs (CC: 155/19) of foreign-born, undeclared children of South Africans, which was negotiated before the Constitutional Court in spring 2020, has not yet been decided in June 2020. At the time, around 8,000 other cases were pending against the Home Office.

- ↑ Act No. 74 of 1983

- ↑ Citizenship Amendment Act, № 17 of 2010, in effect Jan. 1, 2013.

- ↑ Refugees Act, № 130 of 1998, amended by № 10 of 2015. The amendment of December 14, 2017 led u. a. a work ban, the associated “regulation”, which has been revised since 2018, thwarted the positive aspects of the law.

- ↑ ”A citizen of a ... [homeland] shall not be regarded as an alien in the Republic [of South Africa] and shall, by virtue of his citizenship of a territory forming part of the Republic, remain for all purposes a citizen of the Republic and shall be accorded full protection according to international law by the Republic. "

- ↑ Olivier, WH (1977).

- ↑ № 112 of 1993. For more information: Anderson, Bently J .; The Restoration of The South African Citizenship Act: An Exercise in Statutory Obfuscation; Connecticut Journal of International Law, Vol. 9 (1993-1994).

- ↑ Further reading: 1) Mallmann, Rudolf; Rights and duties in the German protected areas: a study of the legal status of the inhabitants of the German colonies on the basis of their nationality; Berlin 1913 (Curtius); 2) Nagl, Dominik [* 1975]; Borderline cases: citizenship, racism and national identity under German colonial rule; Frankfurt 2007 (Peter Lang).

- ↑ The ordinance № 2 of July 19, 1915 provided that women, children and officers could apply on their word of honor to return home to the German Reich (via a neutral port). (Official Gazette of the Protectorate ..., № 1, p. 2.)

- ↑ C mandates were initially considered areas without citizenship. There was no provision for Germans to remain when the peace treaty was drafted. Walvis Bay was co-administered from 1922-77 .

- ↑ Detailed in: Ruppel, Julius; The London Understanding on the Germans in South West Africa; Kolonial-Warte: Correspondence for German colonial propaganda at home and abroad, Jan. 19, 1924.

- ↑ Wempe, Sean Andrew; “O Africa, my soul has remained in you” and Echte Deutsche or Half-Baked Englishmen: German Southwest African Settlers and the Naturalization Crisis, 1922–1924; ch. 2, 3 in Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, Imperialism, and the League of Nations; Oxford 2019; ISBN 9780190907211 ; [DOI: 10.1093 / oso / 9780190907211.001.0001]

- ↑ № 30 of 1924.

- ↑ Official Gazette SWA July 16, 1928 . This closed some gaps.

- ↑ Naturalization and Status of Aliens Amendment Act, 1942 (№ 35 of 1942)