Homeland

As Homeland (German: home area ) were during the apartheid era in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia ; see homelands in South West Africa ) geographically defined areas of the Black called, where a traditionally-related and predominantly high proportion of black African population lived and still lives. With the creation of homelands, the segregation , isolation and fragmentation of the black population received a spatial-administrative structure.

overview

The concept of racial segregation was implemented territorially and socially on the basis of "separate development" and attempts were made to create formally independent states of blacks in South Africa. The homeland residents were given an apparent independence with an autonomous administration. The homelands, however, remained under the economic, administrative, financial and regulatory control of the South African Bantu administration . In fact, they merely represented territorial units that were separated from the rest of the state and largely self-governing.

The blacks who continued to work in South Africa and therefore lived in townships or dormitories became strangers in South Africa in the course of this development. They had no permanent right of residence there and no other civil rights. Blacks who did not live in the homelands were assigned to an ethnic group corresponding to at least one of the homelands. In the course of the independence of the homelands, enforced by the South African government, this led to the forced expatriation of those affected from South Africa. With this approach an attempt was made to change the numerical preponderance of the black nationals of South Africa in favor of the whites. This political act was condemned by the United Nations . Apart from South Africa no state recognized the homelands as independent states. The South African organization ANC , which turned politically and later militarily against apartheid, always rejected the homelands.

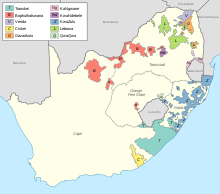

There were ten homelands. In 1963, the Transkei was the first homeland to receive the right to govern itself. Four homelands were declared independent by South Africa, the first being the Transkei in 1976. In 1994 all homelands were dissolved and integrated into the newly created South African provinces.

The independent states of Lesotho and Swaziland were not homelands, even if their geographical location within South Africa was reminiscent of that of the homelands.

Origin and development

Steps to homeland formation

The predecessor structures of the institutionally promoted homeland formation from 1945 onwards result from traditional tribal areas and agreements from earlier wars between the white and black conflict partners, on the basis of which regions with respective majority populations emerged. The first legislative basis for the beginning homeland development (then called native reserves ) came in 1923 with the Native Urban Areas Act , a law on the basis of which the influx of non-white populations into urban areas should be controlled and their behavior should be controlled. The immediately effective legal basis for the establishment of the homelands emerged in South Africa in 1945 with the Bantu Areas Consolidation Act and in 1950 with the Group Areas Act (supplemented by the Native Urban Areas Amendment Act in 1957 ).

From 1958 to 1966 the sociologist Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd was South African Prime Minister, but since 1950 he was responsible for these goals as "Minister for Native Affairs". During his term of office, the reshaping of the reservations in Homelands fell on the model of the Native Administration policy that was customary in Natal in the 19th century . Verwoerd's goal was to create independent homelands without losing blacks as cheap labor in the white economy. This policy of separation or segregation aimed to justify social differences and economic inequalities.

With the homeland policy, a large part of the black population was outsourced, not least to prevent a unitary state ruled by blacks. Verwoerd spoke of the multiracial unitary state . He developed a four-pronged policy that was supposed to promote whites , blacks, coloreds and Asians in parallel. He understood this policy as a decolonization process.

Resettlements were also pushed. The worst affected were black tenants and owners of so-called black spots (German: "black spots", but analogously "dangerous problem areas"), which were blacks who were affected by the Natives Land Act (Act No. 27/1913) of In 1913 they bought land outside the later homelands. Thousands of urban blacks were deported to the former reservations. In particular, the old, sick and weak, who were considered unproductive, were affected.

Constitutional Development

according to Manfred Kurz:

The Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act No. 46 of 1959 provided concrete steps to develop self-governing homelands from the existing reservations and laid the foundation for depriving the black population of their South African civil rights. The immediate basis for the administrative structure in the homelands was created with the Bantu Authorities Act No 68 of 1951. There was a three-stage administrative structure.

This laid the foundation for combining the 42 previous reserves in eight homelands by connecting smaller Bantu areas to larger ones by swapping land. The number of homelands was later increased to ten. The homelands were based on linguistic and cultural differences, but could no longer accommodate ethnic differences as well as the reservations. The rulers of the different Bantu ethnic groups liked to have a "white buffer zone" to distinguish themselves from other Bantu groups. Most of these zones were lost as a result of the consolidation.

Verwoerd's ideology, like that of his successors, had many consequences. What was completely new was the tendency not to view the various Bantu peoples as an ethnic unit, as was previously the case, but as isolated ethnic groups. A black identity should be avoided and the feeling of togetherness weakened. Each Homeland give a white Commissioner (Commissioner), who acted as the official representative of the government.

The administrative structure was designed according to the respective developments in the various homelands. The process, which was initiated and controlled by the highest “Bantu authority” in Pretoria , took place in three phases:

- in the territories there is a self-government with legislative powers

- the homeland achieves the status of a Self-Governing Territory within the Republic (German: "Self-administered area within the Republic")

- The homeland is declared an independent state by the Union parliament on the basis of a law.

The homelands received a three-tier administrative structure. These were the authorities:

- Tribal Authorities

- Regional Authorities

- Territorial Authorities

There was resistance in all homelands to the introduction of administrative structures in the implementation of the Bantu Authorities Act . This took on the character of revolts in many places, as the paternalism by the "white" South African state became evident. In the course of these protests, the police deported tribal chiefs or attacked the angry rural population with machine guns, armored vehicles and military aircraft. Mass arrests followed, in connection with which 11 death sentences were passed.

With the Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act No 26/1970 a legal regulation was created for citizenship in the homelands (according to the law: Transkei and other "self-governing" areas), which however had no international binding force and was only legally effective within the Republic of South Africa. The law also provided for the issuance of their own identity papers for residents of the areas affected by this law.

Actual Position of Chiefs and Other Native Authorities

The hierarchical structures among the indigenous population in the homelands were based on modified traditions of their old tribal cultures. According to the traditional distribution of roles, the head of an ethnic group was a paramount chief, in the case of the Zulu a king. The layer under it formed regional chiefs (Chiefs) . They supervised the headmen responsible for smaller areas or settlements. These authorities had a direct obligation to their people. Even with the British colonial system, the native administration at that time had grown successfully into the traditional power structures. Accordingly, the headmen and chiefs were seen as the preferred contacts because their local authority was strongest. The apartheid strategists took up this initial situation and modified it in line with the country's political doctrine. This was done with the help of the superiority of administrative and budgetary instruments of the state, whereby the responsibility structures of the chiefs were separated from the native population and assigned to the Bantu administration . The associated strict dependence on the "white" supremacy diametrically reversed the original relationship to the tribal population. The respective magistrate, i.e. the regionally responsible department of the native ministry, was responsible for managing and controlling the chiefs. In daily practice he trained them to obey ahead of schedule, which excluded criticism of the magistrate's actions. With the Paramount Chiefs or the Zulu King, the authority tried a strategy of counter-barring. In doing so, she weakened their influence on the chiefs, but gave the tribe or people the impression that their highest authority could supposedly act independently.

The instructions for the administrative actions of the chiefs came from the respective magistrate of the Bantu administration. This “white” authority saw the chiefs, traditionally endowed with relatively extensive powers, as the lowest level of administration and merely the executive body of their policy. Even with their publicly executed vocation, the actual balance of power was demonstrated to the native population in an impressive way until the 1960s. The transfer of the chie function was carried out by the responsible Commissioner of the Homeland and other high officials from the Ministry in a ceremony determined according to their specifications. After the chief candidate had been solemnly welcomed by the population, the commissioner explained the election, instructed the person to exercise his office responsibly and asked them to cooperate closely with the “white” magistrate. As a highlight, the Commissioner, together with the Paramount Chief, declared the intended person to be installed in their new office. In the speeches that are usual here, the call for loyalty to the “white” power was at the center of the statements. As a symbolic gesture, chiefs received a leather briefcase with their inauguration, which was intended to underline their future role as civil servants and servants in the apartheid system. Obligation to loyalty and de facto powerlessness had such an impact that chiefs were punished if they contradicted the orders of the magistrate, criticized them or reported abuses to the supervisory authority. In other cases, the administration referred them back to the officials criticized.

Management levels

to

Tribal Authorities

Tribal Authorities means “tribal authorities” or “tribal administration” in German. The constitutional structure of the early homeland administration was based in its lowest levels on the traditional structures of the chiefs , which at that time no longer fully corresponded to the original tribal relationships.

In the homelands, the chief and an assigned group (the council) form the lowest level of authority. Most of the council members were chosen by the chief. The remaining council members were appointed by a posted white loan officer (Native Commissioner, later Bantu Commissioner) . These groups together formed the so-called Tribal Authorities .

background

Due to the growing proportion of migrant workers in the black population, the role of the chiefs as "administrators" of the traditional tribal country has been subject to considerable change and weakening and thus their authority over the original economic livelihood of their subjects. They were the successors of the old chief lineage .

The original community spirit dissolved, accompanied by a rapid decline in power of the conservative chiefs. This is where the concept of homeland politics according to the apartheid concepts comes in. In the white "Bantu administration" of the state, the Department of Native Affairs , their dwindling position of power was taken up in a way that tribalism was promoted from a new perspective. In their striving for the originally existing power and authority, the chiefs were integrated into the state Bantu administration and the government used them with their patterns of action to implement their policy of racial segregation.

Elimination of civil rights and increase in corruption

In the course of the gradual introduction of the apartheid laws, with the help of the chiefs within the new Bantu administrative structures, the existing claim to an equal status of the black population as sovereign citizens of South Africa was undermined . The original legitimation from the circle of their population based on traditional tribal democracy was finally dissolved. The chiefs now received their authority from a new administrative hierarchy that rose to the power centers of apartheid politics. This system is referred to as the indirect rule of whites over the black population, combined with the use of violence when necessary.

As the extended arm of apartheid politics, the chiefs quickly lost their previous reputation within the population they only apparently represented. This condition turned into a widespread attitude of contempt and rejection. An attitude spread among the black population through the Chiefs that can be outlined with a quote as "drunk illiterate". The situation also resulted in violent attacks resulting in death. The state "Bantu Administration" took those events as an opportunity to provide the chiefs with weapons and security personnel.

In addition, the apartheid practice based on the principle of divide et impera promoted their rule very generously by opening the way to a higher education for their children and other relatives who served the system. In numerous cases, illegal material benefits took place, such as the sale of service mansions at minimal prices and the transfer of land from the assets of the Bantu Trust . In Transkei, the later head of state, Emperor Matanzima, and his brother received two farms for free use. Corruption processes within the chief rulership were tolerated by the upper levels of the (white) "Bantu administration" and brought about an even stronger bond between the homeland exponents and the ruling politics, which turned many of this group of people into unscrupulous opportunists. If the Chiefs defended themselves against the homeland policy, no consideration was given to their traditional position. True to the model from Natal, they were discontinued without further ado and replaced by men loyal to the government.

Regional Authorities

The next level above the tribal authorities were the regional authorities . They were composed of the tribal authorities of the region. The chairman was the oldest chief, or a chief proposed by that body, who required the approval of the Minister of Bantu Administration.

The role of the regional authorities was to provide advice to the minister. On his decision, they could be given powers to build and self-manage hospitals, dams, agricultural structures, traffic routes (except railways) and schools.

Territorial Authorities

The highest level of self-government in the homelands was always the territorial authority. Their representatives came from the regional authorities. After attaining the status of self-government, they were converted into parliaments. Upon reaching this stage of development, the Bantu Administration of Pretoria prepared the step towards state independence.

Expansion of the homelands

Racial segregation shifted poverty from the cities to the reservations and later homelands. Accordingly, the population has increased continuously in the reservations since 1900 and especially 1913 ( Natives Land Act, Act No. 27/1913 ). While in the “white” areas of South Africa an average of 35 people per square mile later came, in the Homelands around 1973 the average was 119 people (values between 61 and 173), over three times as many. This process has been greatly accelerated by the strong industrialization of South Africa since the 1930s. Industrial conurbations with a correspondingly growing resident population emerged.

The population in the homelands increased steadily between 1948 and 1970 as a result of forced relocations. From 1960 to 1970 there were 1,820,000 people. According to the May 1970 census, the homelands were home to 6,997,179 people. By dividing the black population of South Africa into so-called national units , all black people were legally assigned to a homeland, even if they did not live there. Accordingly, the homeland population in 1970 was 15,057,952 people.

On the other hand, agricultural production in the homelands fell drastically within the same period. The arable area decreased because of the increasing population density, the erosion caused by overgrazing and the burning of pastures . The result was a massive impoverishment of the homelands and, in their search for work, a growing need for the Bantu, mainly men, to emigrate to the cities. According to investigations by the Tomlinson Commission in the early 1950s, 74 percent of the reserve area was severely affected by such erosion phenomena. In 1972, the University of Natal again found that over 70 percent of the arable land was of poor quality or completely unsuitable.

Effects of homeland politics

The resulting political effects in the course of this development led to a complete reversal of the function of all chiefs. They used to be the traditionally democratically authorized representatives of their councils and the entire group / tribe to which they were held accountable. Now, as tribal authorities, they have already received their legitimacy from the higher Bantu administration at this lower level of homeland administration. At the same time, the constitutional principle of a democratically elected legislature for this part of South Africans was effectively eliminated.

This hopeless situation created massive emigration in the homelands. The people strove to escape the arbitrary chief despotism, especially since they could not be voted out by them. The immediate effect was an almost unmanageable increase in the resident population in many townships outside the homelands under inhumane conditions (informal settlements). As a result of this development, the political situation in South Africa came to a head and apartheid policy reacted by intensifying the repression with the means of legislation, the use of armed forces and police-state measures. In some townships, public order, health care and education systems collapsed.

However, this was not the only reason the segregation policy met with high criticism. Those in charge were accused of bringing some benefit to only a small number of blacks; Blacks living outside the homelands in particular lost the last remnants of their economic and political rights, but they continued to depend on the city, as the homelands could only support around a fifth of the black population.

These conditions finally prepared the broad basis for an ever-growing resistance movement in South Africa among the black, colored, Indian and a small part of the white population. The predominantly non-violent resistance up to around 1960 had its ethical-conceptual basis mainly in the training of many actors at earlier mission schools and in committed work from the ranks of the Anglican Church at home and abroad. More and more international support came from many countries around the world.

Homelands in independence

Apartheid politicians had long planned to achieve full state independence for the former reservations. President Verwoerd mentioned this goal in his inaugural address as early as January 1959. In 1971, the South African parliament passed the Bantu Homelands Constitution Act to provide the homelands with the envisaged attainment of such state independence and the associated abolition of the respective territorial authorities with white and black administrative staff ( Act No. 21/1971 ).

Most homelands held elections after their formal independence. Apart from Transkei, where the first elections were held on November 20, 1963, this procedure for creating homeland parliaments did not take place until the 1970s in the other areas.

Independence was declared for:

- Transkei on October 26, 1976 (prepared by the Transkei Constitution Act of 1963)

- Bophuthatswana on December 6, 1977

- Venda on September 13, 1979

- Ciskei on December 4, 1981

As a group, these four homelands are sometimes referred to as TBVC states (after the first letters of their names).

Most of the homelands were not territorially closed areas. Ciskei and QwaQwa were largely connected, the homelands Transkei, KwaZulu , Gazankulu , KwaNdebele , Bophuthatswana, Lebowa , Venda and KaNgwane were not connected . There were several so-called consolidation measures, with which a centralized territorial division of the individual homelands was pursued.

By passing more laws, the apartheid regime worked to give all homelands independence. With the Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act of 1970, all blacks should now become citizens of a homeland, including those who lived outside of those areas. The residents of the homelands thus had two nationalities: an internal one, that of their homeland, and an external one, that of South Africa. With the formal independence of the state, the citizens of these four Bantu states lost their citizenship in South Africa.

With the Bantu Homelands Constitution Act ( Act No. 21/1971 ), the government was able to install various levels of self-government in the homelands a year later. The steps towards independence were as follows: First, a legislative assembly was established as a precursor to a parliament. This was authorized to issue laws in certain internal areas. In a second step, after the granting of the internal self-governing the Executive (was Executive Council ) transformed the territorial authority to a cabinet which a Chief Minister board. All portfolios, except defense and external affairs, have now been transferred to this homeland government.

Also in 1970 the Constitution Amendment Act was passed, according to which the South African president could recognize one or more African languages as the official language of the country.

One has to speak of “quasi-independence” because the homelands were actually officially independent, but economically heavily dependent on South Africa and thus could never operate independently. About three quarters of all homelands income came from the government budget of South Africa.

The four “sovereign states” mentioned above were never recognized internationally. Other ethnic groups , above all the Zulu under Mangosuthu Buthelezi , had successfully fought against the autonomy of their homeland, KwaZulu .

President De Klerk planned the reintegration of all homelands into the territory of South Africa as quickly as possible. The ANC opposed this plan in the negotiations with the argument that the integration should only take place under a new, democratic constitution and not under the regulations of the constitution from the apartheid period. With the end of this historical chapter in South Africa, the homelands were finally administratively integrated into the nine reorganized provinces of the republic on April 27, 1994 (parliamentary elections from April 26 to 29, 1994).

Life in the homelands

In 1960 around two-fifths of all South African blacks lived in Homelands. By 1985 this proportion rose to around two thirds. In between, 3.5 million blacks had been resettled from urban areas to the homelands. The area of all homelands taken together comprised around twelve percent of the state land. However, the homelands were not evenly distributed across the state.

Social and economic situation

The poverty in the homelands was enormous. The residents of the Homelands were not only disadvantaged by the above-average number of old people, children and the sick, but were also exposed to discrimination by whites. The government spent five times as much on educating a white child as it did on a black child. The education of blacks also suffered from the fact that many young men had to drop out of school in order to support the family financially. Only about 14 percent of all school-age children completed school. Most blacks had no vocational training and had to settle for lower-paid jobs.

In addition to the massive forced resettlements, there were other attempts to drive the black population out of the white areas. One of them was the promise of job opportunities alongside agriculture. In 1962 there were around 1.4 million black people in Transkei. Of these, only 20,592 had a job within the homelands. Many residents worked outside the homelands, for example in the mines, as migrant workers. Access to these poorly paid workers was a central goal of homeland politics. In order to make even more systematic use of this workforce and to save infrastructure costs, the homelands were partially expanded in the 1980s, so that nearby black urban settlements were integrated into the homelands. The Umlazi settlement, for example, near Durban , became part of KwaZulu, or Mdantsane , near East London , was incorporated into the Homeland Ciskei. The government also gave industrial companies tax breaks if they decided to locate their operations near the borders of the homelands.

Educational structure

The political concept of the homelands was closely linked to education. The Bantu Education Act of 1953 not only enacted inferior education for the black population in South Africa, but also influenced their political attitudes. The intended low rate of graduation was only intended to serve the controlled offspring for the self-governing authorities in the homelands.

A central goal of educational policy was to consolidate the thesis of a "return to the tribal community". Although this demographic-cultural form had long since been disintegrating due to industrialization and the enormous proportion of migrant work in the country, it served to cement the chief structures and their integration into the apartheid administration by the Department of Native Affairs . This principle was implemented methodically with the strict introduction of the mother tongue principle in schools for the black population. The criticism saw this as a retribalization of South African society, which feared ethnic fragmentation on the national territory. The progressive homeland policy and its consequences confirmed this criticism.

In the homelands there were state schools and those under the responsibility of the community associations. The system of the politically independent mission schools widespread in the country had been largely nationalized from 1953 onwards. There was a higher education only in the Ciskei, at the College of Fort Hare , whose work was significantly restricted from 1959 on the basis of the Fort Hare Transfer Act because of positions critical of the government and multiple large student protests . The teaching body, working in the independent spirit of over a hundred years of Anglican missionary work, and the emancipatory traditional foundations of these institutions made them suspect in the eyes of apartheid politics and they appeared to be a threat to the state. In the 1970s the ANC felt compelled to set up the SOMAFCO camp, a temporary substitute facility in exile on the territory of Tanzania , because of the intensified repression measures . Some of the Fort Hare faculty followed this activity.

Ethnic composition

The homelands were built with different ethnicities in mind. Each ethnic group should therefore have its own territory that belonged almost exclusively to them. The classification according to "ethnic" aspects was done by the native administration and from their point of view. For this purpose one created the name National Unit (German: Nationaleinheit).

According to the South African census of 1970, Bophuthatswana was the most “ethnically” heterogeneous homeland. 68 percent of the 880,000 de facto residents belonged to the Tswana . The proximity to the industrial area with mainly mining activity around Pretoria - Witwatersrand attracted further ethnic groups. In addition to the Tswana, around 8,000 whites, coloreds and Asians, there were also a number of Xhosa , Pedi , Basotho , Shangana-Tsonga and Zulu living in Bophuthatswana . In each of the other homelands a single ethnic group made up almost the entire population: the two homelands Transkei and Ciskei were inhabited by the Xhosa to 95 and 97 percent respectively. In KwaZulu the Zulu formed the majority with 97.5 percent, in Lebowa the Pedi with 83 percent, in Gazankulu the Shangana-Tsonga with 86 percent, in Venda the Venda with 90 percent, in QwaQwa the Basotho with 99.6 percent.

Official languages

The official languages in the homelands were legally regulated by South African laws from 1963 (Supplementary Act to the South African Constitution Act ) and 1971 ( Constitution Amendment Act , Act No. 1/1971). Thus prepared English and Afrikaans equal official languages. The President specified in the decree recognizing one or other Bantu languages as such "self-governing" in the respective Bantu area in addition to the mentioned languages.

"Bantustan"

The term “ Bantustan ” (composed of “ Bantu ” and the Persian suffix “-stan”) equates Persian provinces and many countries with the suffix “-stan” (Afghanistan, Pakistan, etc.) with dependent, politically unstable structures and is derogatory. The use of “Bantustan” instead of “Homeland” is internationally common in academic literature and media coverage. The use of the term concentrates on textual contexts in which a critical and negative attitude towards South African homeland politics is expressed. Until 1948, it was customary in South Africa to refer to the rural residential areas assigned by the government to blacks as "reservations". Then the term changed to "Bantustan" and was replaced in 1959 by "Homeland". Later, the authorities referred to some of these areas as "nation-states" because their formal independence from South Africa was sought during apartheid.

The term “stān”, plural “stānhā”, only denotes a “country” in Persian, without a negative connotation; Calling the dependent homelands "Bantustan" is therefore problematic.

The term “homeland” was also seen as a euphemism , although contrary to the original official English term “reserve” it has become generally accepted. The areas referred to as "home country" in German translation were not the actual home for all people associated with them. Through the legislation , the black population was divided into so-called "national units" (correspondingly in German: "national groups") by identification document and assigned to a specific homeland, regardless of their habitual residence, which was to receive full state independence at a later date.

Overview of the ten homelands

| Homeland | National Unit | Self-administration | Independence | Number of areas | Area (1994) | Population in millions (1994) | Capital (1994) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transkei | Xhosa | 1963 | 1976 | 3 | 43,654 | 3.39 | Umtata |

| Bophuthatswana | Tswana | 1971 | 1977 | 7th | 40.011 | 2.19 | Mmabatho |

| Venda | Venda | 1973 | 1979 | 2 | 6,807 | 0.61 | Makwarela ( Thohoyandou ) |

| Ciskei | Xhosa | 1972 | 1981 | 1 | 8,100 | 0.87 | Bisho |

| KwaZulu | Zulu | 1977 | - | 10 | 36,074 | 5.6 | Ulundi |

| KwaNdebele | Ndebele | 1981 | - | 2 | 2,208 | 0.64 | KwaMhlanga |

| KaNgwane | Swazi | 1981 | - | 2 | 3,917 | 0.76 | Louieville |

| QwaQwa | South Sotho | 1974 | - | 1 | 1,040 | 0.36 | Phuthaditjhaba |

| Gazankulu | Tsonga-Shangana | 1973 | - | 4th | 7,484 | 0.82 | Giyani |

| Lebowa | Pedi | 1972 | - | 8th | 21,833 | 3.1 | Lebowakgomo |

With the Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act ( Act No. 46/1959 ), the apartheid system divided the African tribal groups living on the territory of South Africa into so-called National Units . This classification was relatively arbitrary. With this law, the parliamentary representation of blacks by white members in the South African parliament ended, which in fact meant a decoupling.

During the apartheid period, the areas of the homelands changed due to consolidations . In most cases there were territorial gains. Not all plans for these area developments have been fully implemented.

literature

- Axel J. Halbach: The South African Bantu homelands - concept - structure - development perspectives. (= Africa Studies. Volume 90). IFO Institute for Economic Research, Munich 1976, ISBN 3-8039-0129-4 .

- Muriel Horrell: The African Homelands of South Africa. South African Institute of Race Relations , Johannesburg 1973.

- Abnash Kaur: South Africa and Bantustans. Kalinga Publications, Delhi 1995, ISBN 81-85163-62-6 .

- Manfred Kurz: Indirect Rule and Violence in South Africa. (= Work from the Institute for Africa Customer. No. 30). Verbund Stiftung Deutsches Übersee-Institut, Hamburg 1981.

- Andrea Lang: Separate Development and the Department of Bantu. Administration in South Africa - history and analysis of special administration for blacks. (= Work from the Institut für Afrika-Kunde. Volume 103). Edited by Verbund Stiftung Deutsches Übersee-Institut. Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-928049-58-5 .

- Heike Niederig: Language - Power - Culture: multilingual education in post-apartheid South Africa . Waxmann Verlag, Münster 2000, ISBN 3-89325-841-8 .

- Barbara Rogers: South Africa. The "Bantu Homelands". Christian Action Publications, London 1972, ISBN 0-632-05354-2 .

- Klaus Dieter Vaqué: betrayal of South Africa . Varana Publishers, Pretoria 1988, ISBN 0-620-12978-6 .

- Gottfried Wellmer: South Africa's Bantustans. History, ideology and reality . Southern Africa Information Center, Bonn 1976.

- Francis Wilson, Gottfried Wellmer, Ulrich Weyl and others: Migrant work in southern Africa. A reader . Southern Africa Information Center, Bonn 1976.

Web links

- Data on all Homelands (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Manfred Kurz: Indirect rule and violence in South Africa . Works from the Institute for Africa Customer, No. 30. Hamburg (Institute for Africa Customer) 1981.

- ^ J. Axel Halbach: The South African Bantu homelands - concept - structure - development perspectives. (= Africa Studies No. 90). IFO - Institute for Economic Research Munich (Ed.). 1976, p. 31.

- ↑ Gottfried Wellmer, 1976, pp. 83-84.

- ↑ 1970. Bantu Homelands Citizen Act No 26. at www.nelsonmandela.org (English)

- ↑ Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act (Act No 26/1970), DISA library of the University of KwaZulu-Natal ( Memento of September 3, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (English; PDF; 237 kB)

- ^ Andrea Lang: Separate Development ... 1999, pp. 39–43.

- ^ Andrea Lang: Separate Development ... 1999, pp. 147–156.

- ↑ Manfred Kurz: Indirect rule and violence in South Africa . Works from the Institute for Africa Customer, No. 30. Hamburg (Institute for Africa Customer) 1981.

- ^ Francis Wilson et al., 1976, p. 41 (quoted from SAIRR , Muriel Horrel: The African Homelands of South Africa . Johannesburg 1973, p. 39), p. 83.

- ^ Francis Wilson et al., 1976, p. 189 (quoted from SAIRR , Fact Sheet 1972)

- ↑ Gottfried Wellmer, 1976, pp. 59-60.

- ^ Francis Wilson et al., 1976, p. 45.

- ^ Christoph Marx : South Africa. Past and present . Verlag W. Kohlhammer , Stuttgart 2012, p. 244

- ↑ Muriel Horrell: The African Homelands of South Africa . SAIRR , Johannesburg 1973, pp. 50-52

- ^ Christoph Marx: South Africa . 2012, pp. 250-251

- ^ SAIRR: Race Relations Survey 1984 . Johannesburg 1985, p. 184

- ↑ Muriel Horrell: African Homelands . 1973, pp. 14-36

- ↑ Muriel Horrell: African Homelands . 1973, pp. 49-50

- ↑ Muriel Horrell: African Homelands . 1973, p. 52

- ^ SAIRR: Race Relations Survey 1993/1994 . Johannesburg 1994, p. 632

- ↑ SAHO : The Homelands . on www.sahistory.org.za (English)

- ↑ Heike Low: Language-Power-Culture. 2000, p. 89.

- ↑ a b Manfred Kurz: Indirect Rule ... 1981, p. 44.

- ↑ Muriel Horrell: African Homelands . 1973, pp. 44, 52.

- ↑ Laura Phillips, Arianna Lissoni, Ivor Chipkin: Bantustans are dead - long live the Bantustans . Mail & Guardian Online, article from July 11, 2014 on www.mg.co.za (English)

- ↑ Bertil Egerö: South Africa's Bantustans. From Dumping Grounds to Battlefronts . Nordiska Afrikainstitutet , Uppsala 1991, ISBN 91-7106-315-3 , p. 6 (PDF document p. 9, English)

- ↑ Christoph Sodemann: The laws of apartheid . Southern Africa Information Center , Bonn 1986, p. 214.

- ↑ Baruch Hirson: Year of fire, year of ash. the Soweto revolt, roots of a revolution? Zed Press, London 1979, ISBN 0-905762-29-0 , p. 332.

- ^ Juta's New Large Print Atlas . Juta, Capetown, Wetton and Johannesburg 1985, ISBN 0-7021-1545-2 .

- ↑ a b Website of the South African Police ( Memento from August 10, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on November 27, 2015.

- ↑ 1959. Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act No 46 . on www.nelsonmandela.org (English)

- ^ Andrea Lang: Separate Development ... 1999, p. 89.