Saint-Médard (Soissons)

Saint-Médard was a Benedictine monastery in Soissons in northern France.

history

The abbey was founded in 557 by the Frankish king Clotaire I. founded. He left the bones of St. Medardus transferred to Soissons and began building a large church over the saint's tomb, while the tomb itself was initially protected by a wooden mausoleum. Chlothar died before the church was completed, and only his son Sigibert was able to complete and decorate the church. Both Merovingian builders were buried in this church ("in basilicam") in front of the Medardus grave ("ante tumulum"). The Frankish-speaking King Chilperic I wrote a Latin hymn to St. Medardus around 575, which has been preserved in a single manuscript.

The abbey also held a prominent position among the Carolingians . In 751 the last Merovingian Childerich III was here . sheared . In Saint-Médard, the church assembly commanded by Lothar I and chaired by Archbishop Ebo of Reims took place on November 13, 833 , which was the second time that Emperor Louis the Pious was deposed. Ludwig was forced to read out a previously drawn up confession of guilt, lay down his weapons, put on a penitential robe, renounce the world and declare himself unworthy of the throne.

Lay abbots from Saint-Médard were u. a. the Carolingians

- Karlmann , 860–870, son of Charles the Bald

- Heribert II. , 907-943, Count of Vermandois

- Heribert the Old , 946–980 / 984, his son, Count of Meaux and Count of Troyes

Destroyed by the Normans and the Magyars , Saint-Médard was rebuilt in the 11th century. During the Huguenot Wars , the abbey was destroyed in 1567, partially renewed from 1630 and finally laid down in 1793 except for the crypt .

From the scriptorium of the monastery comes the Évangéliaire de Saint-Médard de Soissons ( Gospels from Saint Médard in Soissons ), a manuscript that was made in the last few years of Charlemagne in the Palatinate School in Aachen . It is one of the most representative examples of Carolingian book illumination at the beginning of the 9th century because of the effort that went into its production and the extent of the composition (for example the size of the painted evangelists) and the quality of its many colors .

Otto von Corvin writes in his church-critical Pfaffenspiegel that the monastery was a kind of “factory of false documents” with which the church had proven non-existent property rights: “The monk Guernon confessed at the death camp that he had crossed all of France in order for Monasteries and churches to make false documents. So it was of course no wonder that at the time of the revolution the fortunes of the clergy in France could be estimated at 3,000 million francs! ”[5. Edition, p. 285]. The strange legends of the monastery also include the relics of the objects allegedly kept there: Jesus' milk tooth, a piece of his umbilical cord and even part of his penile foreskin after the circumcision. But for logical reasons that cannot be true. So far, I have not been able to find any evidence of the existence of Maria’s shoe, which is often quoted there.

Buildings and plant

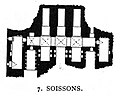

The French art historian Lefevre-Pontalis developed four successive construction phases of the 6th, 9th, 12th and 16th centuries for the abbey church of Saint-Médard based on written sources. The time of origin of the only crypt still preserved from the sacred building is controversial in the literature. Lefevre-Pontalis begins its creation between 826 and 841, Jacobsen contradicts this and dates it to the first half of the 11th century. The sources document the existence of the crypt for the first time in 1079. It was not an isolated building or was added later, but was built together with the abbey church; its formal language is closely related to the crypt of St. Willibrord zu Echternach . Of three chapels added in the 12th century, the southern one has been preserved; it was renovated in 1970. Saint-Médard itself was an elongated three-aisled basilica with vaulted aisles. In its eastern third, flanking rectangular towers were leaning against it. In the west of the nave there was also a full-width west building in front of which two strong rectangular towers were leaned on both sides, so that the west building turned into a broad western front. The crypt extended under the eastern main altar and measures 30 meters in width.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Reconstructed, edited in Latin and translated into German by Udo Kindermann : King Chilperich as a Latin poet . In: Sacris erudiri 41 (2002), pp. 247-272

literature

- Werner Jacobsen: The former Saint-Médard abbey church near Soissons and its preserved crypt . In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 46 (1983), pp. 245–270.

- Udo Kindermann : King Chilperich as a Latin poet . In: Sacris erudiri 41 (2002), pp. 247-272

- E. Lefevre-Pontalis: Etude on the date de la crypte de Saint-Medard de Soissons . In: Congres archeologique 54 (1887), pp. 303-324.

Web links

Coordinates: 49 ° 22 ′ 59 ″ N , 3 ° 20 ′ 37 ″ E