Joke and seriousness

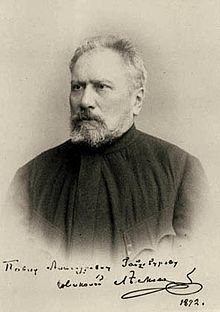

Scherz und Ernst ( Russian Смех и горе , Smech i gore ) is a story by the Russian writer Nikolai Leskow , which appeared in sequels in the Sovremennaja letopis , a weekly supplement by Katkov's Moscow Russki Westnik , in early 1871 .

overview

The landowner Orest Markowitsch Wataschkow, descended from the old Russian nobility, has experienced hair-raising events.

Born abroad, six-year-old Orestes lost his father in a boat accident off Genoa . Two years later, the mother and the boy went back to Orestes uncle's home in the southern Russian province. Orestes inherited around two thousand farmers, studied in Moscow, Saint Petersburg and Bonn , became a hussar against his will in the military , then a cornet around 1855 , studied again abroad, returned to Petersburg in 1868 and remained single until his death. The narrator quickly announced the end of Uncle Orestes: In 1871 Orestes wanted to return to his foreign country. On his way out, he was caught in the 1871 pogrom against the Jews in Odessa , was flogged in this port city by a Russian captain who brought order and died as a result.

The text offers a wealth of events on European history from the middle of the 19th century - primarily relating to Russia - predominantly in meticulous dialogue. From the detailed corpus only one of the narrative-shaped sequences developed by Leskow is to be sketched: the involuntary confrontation of the protagonist Orestes with two members of the third department . The third division was the secret police in the Russian Empire . This was headed by General Dubelt from 1839 to 1856 . Of course, nothing of the secret police - but nothing at all - is mentioned by name in this prose piece. As a result, the text appears cryptic. However, the reader learns what Leskov actually means by his allusions from comments in footnotes that Russian and German editors added in the 20th century. For example, a blue being is a soldier or officer in the secret police. They wore blue uniforms. Or another example - the secret police Postelnikov does not call the protagonist Orestes, but Filimon - a reference to his alleged name day, December 14th, the day of the Decembrist uprising . Towards the end of the text, Police Captain Postelnikov made it. The babbler has risen to become a general.

The third department

Orestes, who studies in Moscow, has to look for a new dormitory there and comes across his new landlord, a certain Leonid Postelnikow, a captain with an "endless flow of words". After Ryleev 's forbidden book Dumy ("Dreams") from the Decembrist year 1825 was found in Orest's booth , he was arrested. He is prohibited from further studies at any Russian university. At the intervention of his uncle, the young man is allowed to study again in Petersburg. Soon Mr. Postelnikow turns up with his new friend Stanisław Przykrzywnicki - simply Staska - and apologizes for the aforementioned arrest. Orestes must understand him too, explains Postelnikov, who cannot explain anything briefly. Postelnikow and Staska had a problem with professional advancement - neither of them had “the slightest power of observation”, one of the indispensable requirements in their trade. So they had to resort to the drastic means of arrest. Orestes accepts and is only amazed how Postelnikov found him again. No problem, adds the captain, "You can see that from our lists."

Kind people politely lead Orestes away in Petersburg. You let him wait in an office. Orestes says: "I was just afraid to move, I lifted one foot and it was as if the other one disappeared into the floor ...". Finally, a uniformed, gray-haired man of very short stature with a huge mustache - the above-mentioned General Dubelt is meant - persuades him to pursue a military career.

title

In this serious satire of the times, Orest's above-mentioned uncle causes the death of Orest's dear mother with a joke. Orestes is jested by two members of the Third Division and forced into the military as an aspiring academic. The latter, in turn, is very serious.

Quotes

- General Dubelt: "We know everything."

- "... in general the Russian is very strong, if you don't spoil it with medicines."

- "You know ... that the increase in the number of the mentally ill has a certain relationship to civilization - there are almost no peasants with mental disorders."

Self-testimony

- Leskow to Suvorin : “When I wrote jokingly and seriously , I began to think responsibly. Since then I have stayed true to this resolution: to take a critical stance, but at the same time ... to be good-natured and indulgent. "

reception

- 1959: Setschkareff sees parallels to Gogol's Dead Souls and to Sternes Sentimental Journey . Regarding the bitter satire of Leskov, he writes: In the Russia of the Tsar in the 19th century "by mistake and as a funny misunderstanding ... you can be officially beaten in public on the street in such a way that you die from it (this is the finite fate of the much tried uncle)."

- 1967: Reissner thinks that Orestes rejects and despises the Russian situation at the time, but it stays that way. The hero does not seriously strive for change.

- 1985: Dieckmann sees the activities of the Narodomists in the 1870s as a renewed attempt to re-attempt the democratic endeavors described here that failed in the 1860s.

literature

German-language editions

- Joke and seriousness. German by Michael Pfeiffer. P. 222–449 in Eberhard Dieckmann (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes. Vol. 3. The sealed angel. Stories and a novel. 795 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1985 (1st edition)

Output used:

- Joke and seriousness. German by Michael Pfeiffer. P. 487–723 in Eberhard Reissner (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes. Love in bast shoes. With a comment from the editor. 747 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1967 (1st edition)

Secondary literature

- Vsevolod Sechkareff : NS Leskov. His life and his work. 170 pages. Verlag Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1959

Web links

- The text

- Entry in the Laboratory of Fantastics (Russian)

- Entries in WorldCat

Remarks

Reissner explains:

- ↑ "Obviously Watashkov was observed by the secret police." (Reissner in the notes of the edition used, p. 737, 4th entry, 1st paragraph)

- ↑ "At that time it was believed that the floor in the rooms of the secret police was made in such a way that those under interrogation suddenly fell into a cellar, where they were beaten." (Reissner in the notes of the edition used, pp. 737, 5. Entry)

- ↑ in the notes of the edition used, p. 737, 6th entry

Individual evidence

- ↑ Russian chronicle of our time

- ↑ Reissner in the follow-up to the edition used, p. 730 above

- ↑ Russian Tretje otdelenije

- ^ Reissner in the notes of the edition used, p. 737, 4th entry, 2nd paragraph

- ↑ Edition used, p. 565, 5th Zvo

- ↑ Edition used, p. 566, 15. Zvo

- ↑ Edition used, p. 568, 12. Zvo

- ↑ Edition used, pp. 560–561

- ↑ Edition used, p. 561, 19. Zvo

- ↑ Edition used, p. 569, 12. Zvo

- ↑ Edition used, p. 701, 9th Zvu

- ↑ Edition used, p. 704, 13. Zvo

- ↑ Leskow, quoted by Reissner in the follow-up to the edition used, p. 730, 17. Zvo

- ↑ Setschkareff, p. 141, 23. Zvo

- ^ Reissner in the follow-up to the edition used, p. 730, 7th issue

- ^ Dieckmann in the follow-up to the 1985 edition, p. 764 middle