Note inflation

Of grade inflation is spoken when increasingly better for the same services of pupils or students in exams over the years marks will be awarded.

proof

The phenomenon of grade inflation has been hotly debated for years in connection with the disappointing results of the PISA studies of 2001, a decline in the ability of the majority of school leavers to study and the question of fairness at schools and universities as well as in public, which universities have complained about . The trend towards increasingly better grades has been known for a long time. For example, the average high school diploma in Baden-Württemberg was 2.8 in the 1970s and 2.5 in the 1980s. In 2008 the average was already 2.32.

There has long been controversial speculation about the cause of this development. On the one hand, the phenomenon could be due to the awarding of better grades for the same performance - that is, grade inflation. On the other hand, it was theoretically thought possible that improved teaching actually led to better performance. A sudden increase in intelligence or the will to learn of the current generation is realistically considered unlikely. Rather, it is assumed that the requirements have been scaled down. In the meantime, scientifically sound statistics and analyzes are available, especially for high school and university degrees , which objectify the fact of grade inflation.

State examination grades

In an elaborate research project at the European University of Flensburg , a total of 138,000 examination files and approx. 700,000 exam grades from seven universities for the years 1960 to 1996, supplemented by 5.3 million data from the electronic exam database of the Kiel State Statistical Office , were the nationwide exam grades for the years 1996 to 2013 and for all German universities.

The focus of the surveys was the determination of non-performance-related influences and the explanation of 'grade inflation', i.e. the causes of an improvement in grades without a corresponding improvement in examination performance. As a summarizing result, the researchers state: Since the 1970s there has been a clear trend towards grade inflation at German universities, which, however, differs according to universities and fields of study and is also cyclical, parallel to the fluctuating demand for trained graduates. As a conclusion, the education economists call for a rethinking of the “grade inflation”, since the grades should be comparable and injustices resulting from the unequal treatment should end.

Abitur grades

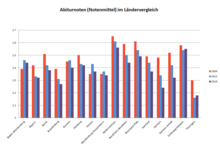

A similar development to the state examination grades can already be observed in the Abitur grades : The official school statistics of the "Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education of the Federal Republic of Germany" (KMK) , their evaluation of the number of exams passed, the overall average grades and the frequency of the individual Records average grade averages in a country comparison confirms the general trend of grade inflation also for the Abitur grades from 2006 to 2019: If in 2006 not even every hundredth Abitur graduate received an average grade of 1.0, the rate increased by more than 50% by 2014 . For example, the Berlin schools awarded the top mark in 2015 five times as often as in 2006 and in 2016 fourteen times as often as ten years earlier.

According to the statistics, Thuringia awarded the grade average between 1.0 and 1.9 with 37.8% in 2013 to its high school graduates, while Lower Saxony was the strictest with only 15.6% when it came to assigning grades. Thuringia is already the mildest of the federal states with a failure rate of only 1.8% in 2009, while Lower Saxony obviously had higher demands with a failure rate of 4%. Overall, the average grade in Thuringia in 2015 was 2.16, half a grade higher than, for example, in the stricter Lower Saxony, which has an average value of 2.59.

The tendency to award top grades with the consequence of a devaluation of the Abitur certificates is also lamented by the teachers 'associations, such as the philologists ' association . The chairman of the German Teachers' Association , Josef Kraus, made a similar statement on December 7th, 2016 with the public statement: " I believe that we have reduced the standards in Germany, but at the same time the grades have got better and better. We have to get out of this dilemma " . The devaluation of the grades with the tendency of “ones for all”, which equates good and less good graduates and makes them difficult to compare, disadvantages the better graduates in particular and poses problems for universities and employers when selecting applicants, which they face with increasing entrance exams search. They also influence the expectations of school leavers and their decisions about university studies as well as the grading there, which is also increased in order to maintain the drop-out rate within limits and the career opportunities.

causes

The most common explanation for grade inflation is the assumption that grade providers at schools and universities are reacting to the increasing pressure in the labor market since the 1970s. Teachers and professors - so the assumption - give their pupils and students better and better grades in order to improve their chances on the increasingly tight job market . Such an approach cannot lead to success if it is practiced across the board.

Another assumption relates to the area of the religious bureaucracy . According to this assumption, educational institutions try to prove the quality of their work with good grades. There is therefore a pressure on schools and universities to tend to give better and better grades in order to be able to demonstrate success against the culture and science bureaucracy.

It is also believed that the higher education phenomenon is increasingly caused by the students' evaluation of the events. It is assumed that professors "buy" a good assessment of their course from the students with good final grades.

consequences

The consequence of the grade inflation is a devaluation of the diplomas. Many universities justify their request to carry out aptitude tests in addition to the Abitur , among other things with the argument that the Abitur grades can no longer be regarded as a guarantee for the ability to study. A similar reaction can be seen on the training market. Many training companies no longer see a good certificate as sufficient proof of suitability to successfully complete an apprenticeship. They also cite grade inflation as a reason for recruitment tests . An essential argument of the educational researchers lies in the comparability of the grades and the corresponding question of fairness regarding the graduates and their career prospects.

See also

literature

- Gerd Grözinger, Volker Müller-Benedict (ed.): Grades at Germany's universities. Analysis of the comparability of exam grades 1960 to 2013 , VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2017, ISBN 978-3-658-15800-2 .

- Federal Statistical Office (Destatis): Education and Culture. Students at universities , Wiesbaden 2017.

Web links

- School statistics Abitur grades - accessed May 27, 2017

Individual evidence

- ^ Tanjev Schultz: Note Inflation. sueddeutsche.de GmbH, August 11, 2008, accessed on September 19, 2010 .

- ↑ 1.0-Abitur grades in Berlin quadrupled - accessed on January 26, 2018

- ↑ Gerd Grözinger, Volker Müller-Benedict (Ed.): Grades at Germany's universities. Analysis of the comparability of exam grades from 1960 to 2013 , VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2017

- ↑ Gerd Grözinger, Volker Müller-Benedict (Ed.): Grades at Germany's universities. Analysis of the comparability of exam grades from 1960 to 2013, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2017

- ↑ Thomas Gaens u. a .: The long-term development of the grade level and its explanation, In: Gerd Grözinger, Volker Müller-Benedict (Hrsg.): Grades at Germany's universities. Analysis of the comparability of exam grades 1960 to 2013 , VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2017, pp. 17–78

- ↑ School statistics Abitur grades - accessed May 27, 2017

- ↑ 1.0-Abi grades in Berlin quadrupled - accessed on January 26, 2018

- ↑ Proportion of high school graduates with an average grade of 1.0 to 1.9 in 2013 - accessed May 30, 2017

- ↑ Failure rate in the Abitur by federal state - accessed May 30, 2017

- ↑ Inflation of the top marks - Die Zeit 19 (2016)

- ↑ Grade inflation at the Abitur - accessed May 27, 2017

- ↑ Focus online v. December 7, 2016

- Jump up ↑ ones for all - accessed May 27, 2017

- ↑ Grade inflation at universities - accessed May 27, 2017

- ↑ Maik Riecken: Note inflation. May 3, 2009, accessed September 19, 2010 .

- ↑ Cuddling notes, horse trading, companionship. spiegel.de, January 17, 2007, accessed on September 19, 2010 .

- ↑ Thomas Gaens u. a .: The long-term development of the grade level and its explanation , In: Gerd Grözinger, Volker Müller-Benedict (Hrsg.): Grades at Germany's universities. Analysis of the comparability of exam grades 1960 to 2013 , VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2017, pp. 17–78