Protection power activity of Switzerland in the Second World War

The neutral Switzerland practiced in the Second World War, a diplomatic activities as a protecting power off. To this end, when the war broke out in September 1939 , the Swiss Federal Council decided to create a department for foreign interests.

With the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany on May 8, 1945 and Japan on September 2, 1945, Switzerland gradually dissolved the protecting power departments and discontinued the war-related protective power activities on March 31, 1946. The statement of accounts of the Department for Foreign Interests of the Federal Political Department for the period from September 1939 to the beginning of 1946 , which was drawn up in January 1946, recorded this activity.

Foreign Interests Department

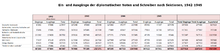

| Swiss | Foreigners | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early 1940 | in Bern | 7th | - | 7th |

| abroad | 17th | 8th | 25th | |

| Early 1941 | in Bern | 11 | - | 11 |

| abroad | 37 | 9 | 46 | |

| Early 1942 | in Bern | 62 | - | 62 |

| abroad | 84 | 314 | 398 | |

| Early 1943 | in Bern | 116 | - | 116 |

| abroad | 271 | 537 | 808 | |

| Early 1944 | in Bern | 140 | - | 140 |

| abroad | 334 | 748 | 1082 | |

| Early 1945 | in Bern | 130 | - | 130 |

| abroad | 374 | 734 | 1108 | |

| Early 1946 | in Bern | 50 | - | 50 |

| abroad | 96 | 324 | 420 | |

Shortly after the German invasion of Poland , the Swiss Federal Council decided on September 8, 1939 to create the Department for Foreign Interests, affiliated to the Federal Political Department (EPD), today the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs ( FDFA ). Inquiries regarding the assumption of protective power mandates had already been received. On August 30, 1939, the Swiss Federal Assembly granted the Federal Council extraordinary powers (powers of attorney) which “normally only belonged to Parliament”.

management

The retired former Swiss ambassador, Minister Charles Lardy, became director. After his sudden death in October 1939, Dr. Hans Fehr , Professor of Legal History at the University of Bern , is his successor. Minister Fehr resigned in June 1940. Minister Arthur de Pury took over the management of the department until April 1945. From April to the end of October 1945, Legation Councilor Jacques de Saussure headed the department ad interim .

Sections

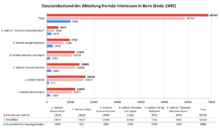

As the war continued, the number of protective mandates increased. The department for foreign interests organizationally divided the mandates into five sections:

- Section: Germany (headed by Jakob Burckhardt, from February 1943 Antonino Janner )

- Section: Italy (headed by Henri Schreiber until the end of 1943)

- Section: Great Britain (Head Charles-Albert Dubois)

- Section: USA and Japan (Head Emil (e) Bisang)

- Section: other states (headed by Robert Maurice ).

A general secretariat and a law firm were created to cope with the flood of files. By the end of 1945, the number of dossiers created was 68,750.

From 1940 onwards, 153 civil servants or salaried employees were employed in the department for foreign interests in Bern and over 1,000 abroad. In countries in which the activity was large, among other things through the care of prisoners of war , independent special departments were set up for the sole purpose of representing foreign interests. In addition, auxiliary workers were recruited, partly on the spot, in order to counter the initial shortage of staff as a result of recruiting difficulties for “trained staff”.

Requirements for Switzerland to take over the representation of interests

During the Second World War, Switzerland only exercised its role as a protecting power upon request by another government. As a rule, she did not respond to private requests. They only took on a mandate if the other side had given their express consent. The government granting the mandate had to submit the request to the Federal Political Department in Bern. The Geneva Prisoner of War Agreement of 1929 served as the basis for international law . However, this agreement merely described the protective power of a state without defining it in a binding manner. For this reason, the Department for Foreign Affairs or, after its creation, the Department for Foreign Interests only considered the mandate to be taken over if the state ( Agrément ) had given its approval , “in whose area of responsibility the representation should take place”. Requests, notifications and complaints from the issuing state for the attention of the other conflicting party (s) were submitted to the Swiss Department for Foreign Interests through its representation in Berne , which forwarded them to the local foreign ministry or the relevant army units via the relevant Swiss delegations on site.

In addition to official interest groups, Switzerland acted as a protecting power even when its activities were only tolerated. These " de facto representations" came about when a state did not recognize another government, as was the case in the course of regime changes (government of Maréchal Pétain in Vichy France ) or governments in exile . Even after the liberation of occupied territories (such as Belgium , the Netherlands , Norway , Kingdom of Yugoslavia or Greece ), in which the occupier, Nazi Germany , consented to protecting power , the representation of British and American interests remained, for example Switzerland often exist.

When relations were broken off, the diplomatic and consular staff had to leave the “host country”, now enemy country, within a “reasonable time”. Your ability to act under international law expired. Often the diplomatic personnel forced to leave the country were arrested, as in Great Britain and Germany. The Swiss Consular Regulations (SCR) were decisive for granting protection to “foreign nationals” by Swiss embassies and consulates . In the annual report of the Department for Foreign Interests of the Federal Political Department for the period from September 1939 to the beginning of 1946, Article 36 is emphasized:

"Foreigners are entitled to the assistance of the consul, insofar as the Federal Council has taken on the representation of their interests by agreement with the governments of their home state and the state of residence. The Political Department will issue more detailed regulations on a case-by-case basis. "

Duties of the protecting power departments of the Swiss delegations on site

As a protective power, Switzerland mediated between the conflicting parties during the war. It forwarded requests or complaints from one of the conflicting parties to the other through its own diplomatic channels. They also tried to ensure the protection and / or care of foreign nationals of the mandating power in the enemy country. Their diplomatic and consular services were basically free of charge. The powers represented paid for the salaries of the department for foreign interests in Bern as well as for the staff of the Swiss embassies there.

Protection of diplomatic and consular staff

After the break in diplomatic and consular relations between two states, the delegation staff is obliged to leave the “host country”. During the Second World War, officials on both the British and the German side were partially prevented from leaving freely in order to allow them to return home in exchange for their own staff detained by the enemy forces.

The protective power activity made Switzerland a mediator, for example between the British and German sides. She conducted exchange negotiations and took care of the appointed staff. The local protecting power departments ensured that the delegation held in the “custody state” was treated “appropriately” and protected against harassment.

Interned personnel were exchanged as far as possible on the soil of neutral states under the guarantee of the government concerned. These exchanges took place in Portugal, Spain, Sweden and occasionally in Switzerland.

Care of foreign nationals

In the warring states, “enemy foreigners” were forced to register. Civilians deemed dangerous or suspicious by the authorities were detained. They were only given protection under international law in the case of international treaties "between the home country and the country of residence" that remained valid.

The 1929 Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War did not provide for any explicit protection of civilians. For example, Article 81 only protected those civilians such as "war correspondents, newspaper reporters, sutlers and suppliers" who were captured following the army and who had an ID card from the military authorities "who accompanied them".

Therefore, the state acting as a protecting power itself decided on the degree of its commitment to foreign nationals. In the case of Switzerland, this meant that it only automatically granted the same assistance as the Swiss citizens to those foreigners with whose government the Swiss Federal Council had entered into an agreement on the representation of their interests.

Legal protection

In general, Switzerland, as a protective power, tried to guarantee the legal protection of those under protection and to intervene on site in the event of disregard for the Geneva POWs (1929), for example. However, those responsible were well aware of the legal gray areas. In the accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests of 1946 this fact was taken into account as follows:

"Naturally, full protection could not be granted during the war, on the one hand because the friendship and settlement treaties [...] were suspended in their effect, and on the other hand because there is still no clarity under international law as to which measures against enemy members are still permissible and which are to be assessed as contrary to international law are. However, the prerequisite for an effective intervention is a legally indisputable basis as possible [.] "

Passport

Legal protection automatically included the issuing of protective passports . Proof of nationality was essential for gaining legal protection against both the protecting power and the state of residence. But also the extension of passports was part of the area of responsibility, whereby this was done "according to the wishes of the home country". In the statement of accounts of 1946, the Department for Foreign Interests praised itself for having saved numerous Jews from being deported from Germany by issuing a protection pass. She emphasized that she had only issued protection passports on the basis of general and, in case of doubt, special authorization from the home country.

The Swiss Vice Consul in Budapest , Carl Lutz , behaved differently , who, together with the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, saved the lives of tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews by issuing protective passports without any general or special authorization.

Care of prisoners of war

As a rule, the protecting power divisions of Switzerland had access to enemy combatants detained in the warring countries. While the Department of Foreign Interests in its report praised the treatment of prisoners of war by the British and American authorities, it underlined the problems with the Japanese authorities, which only granted access to Japanese prisoner-of-war camps after countless demarches by the Swiss protecting power in 1944 . The main problem was the failure to sign the 1929 Agreement on the Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Japanese government. But even in the signatory states to the agreement, not all facilities were accessible for inspections. For example, the Swiss protecting power department in Berlin was given access to 13 German camps in the Reich and in the occupied territories, but not the concentration camps in the German area of influence, "which, according to the German view, belonged exclusively to domestic politics."

"It turned out that the war leaders attached great importance to the cooperation of the protecting power and the International Committee of the Red Cross in the question of the treatment of civilian internees as well as prisoners of war [.] [...] The experiences with Japan were also unpleasant here."

Similar to the exchange of interned civilians, Switzerland also advocated the mutual exchange of wounded or sick prisoners of war between the conflicting parties. For example, in October 1943 around 11,000 British and German soldiers were able to return to their homeland via Gothenburg , Oran and Barcelona .

Delivery service

Due to the mutual representation of the warring parties, Switzerland assumed the role of "postman". The powers involved communicated their requests to the Foreign Interests Department through the diplomatic missions in Bern . The relevant foreign ministries, in the case of prisoners of war, the competent war ministries or “competent army units”, were informed of the matter via the Swiss missions in the countries of the addressees.

However, the department for foreign interests took out a "certain right of examination". Whenever possible, she forwarded protests as the original text, but withheld injurious or threatening notes. Two exceptions are given as examples in the accountability report. After the fall of the fascist Prime Minister Benito Mussolini at the end of July 1943, the British government threatened the Italian government with consequences in the event of the deportation of British prisoners of war from Italy to Germany. The American government sent "sharp notes" to those of Hungary via Switzerland in order to demand the cessation of the deportations of Jews to Auschwitz.

Financial support for wards

The Swiss embassies on site provided needy nationals of the mandating powers, civilians as well as prisoners of war, financial support. These were made available to Switzerland by the warring parties either in the form of advances or monthly and quarterly payments. The so-called “free-living” received support for their livelihood, the detainees received pocket money. However, the amount of the benefit paid out was extremely manageable:

“In many cases, however, the help provided was insufficient and varied greatly depending on the circumstances. Even the internees, who were privileged in a certain way because their material life was more or less secure, were mostly unable to satisfy even the most primitive cultural needs due to a lack of earning opportunities [...]. "

Nevertheless, by the end of 1945 Switzerland had paid out around 245 million Swiss francs in support.

Protection of foreign public and private property

By taking over the representation of interests on site, extraterritorial property such as the official building and archives became the property of the Swiss protecting power departments. The Swiss staff kept detailed inventories of the takeover . Inventory lists from the Swiss protecting power departments can still be viewed in the Swiss Federal Archives in Bern. Buildings and rooms that were not useful for carrying out the protecting power activities had the protecting power departments sealed.

However, the properties managed by the protection department were partially damaged or destroyed by the ongoing war. Nor was this protection sacrosanct. After the occupation of free France by German and Italian troops in 1942, certain files were stolen from the American embassy in Vichy, which was under Swiss protection, and the German buildings in Rome , which had been declared an open city , were opened in June 1944 after the "Swiss embassy there" was taken over Searched explosives and declared the international legal protection of this extraterritoriality to be abusive: The abuse "could not be proven in Vichy, but in Rome, where an explosives store was found in the embassy basement."

Private property in all forms (movables, real estate, patents, trademarks, copyrights, etc.), on the other hand, was not protected under international law. The protecting power was limited to transmitting measures issued in enemy territory and the resulting effects on the blocked and / or confiscated objects. The intention of the Swiss delegations was to find a tolerable business deal for foreign governments or private companies after the break in diplomatic, economic and financial relations between the conflicting parties.

literature

- Dominique Frey: Between "postman" and "intermediary". Swiss protective power activities for Great Britain and Germany in World War II . In: Marina Cattaruzza, Stig Förster, Christian Pfister, Brigitte Studer (eds.): Bern research on the latest general and Swiss history . Volume 6. Verlag Traugott Bautz, Nordhausen 2006, ISBN 3-88309-381-5 .

- Georg Kreis : Switzerland in the Second World War. Haymon-Verlag, Innsbruck / Vienna 2011, ISBN 978-3-85218-868-3 .

- Paul Widmer : The Swiss Legation in Berlin. History of a difficult diplomatic post. Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-85823-683-7 .

Web links

- Bisang, Emile in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- Burckhardt, Jakob in the Dodis databaseof diplomatic documents in Switzerland

- Digitized holdings of the Swiss Federal Archives ( online official publications )

- dodis.ch : Database of the independent research project Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland (DDS)

- Dubois, Charles Albert in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- Janner, Antonino in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- Lutz, Carl in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- Maurice, Robert in the Dodis databaseof diplomatic documents of Switzerland

- Saussure, Jacques de in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- Schreiber, Heinrich in the Dodis databaseof diplomatic documents in Switzerland

- Wallenberg, Raoul in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

Individual evidence

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 20. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ^ Online official publications SFA: Report of the Swiss Federal Council on its management in 1946 . ( From April 1, 1947). In: Annual reports of the Federal Council . Volume 92, 1947, pp. 1-453, here: pp. 139, 152.

- ^ Andreas Kley: Power of Attorney Regime. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . August 26, 2013. Retrieved May 16, 2017 .

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 3. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ^ Online official publications BAR, report from the Federal Council to the Federal Assembly on all resolutions and measures in force that were taken on the basis of the extraordinary powers, as well as on the intended fate of these resolutions. (December 10, 1945) . In: Federal Gazette . Volume 2, No. 26, 1945, pp. 559–706, here: pp. 561–565, accessed on May 16, 2017.

- ↑ Lardy, Charles Louis Etienne in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ^ Fehr, Hans in the Dodis database of diplomatic documents in Switzerland

- ↑ Lukas Gschwend: Hans Fehr. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . January 3, 2005 , accessed May 17, 2017 .

- ^ Pury, Arthur de in the Dodis database of diplomatic documents in Switzerland

- ^ Sarah Brian Scherer: Arthur-Edouard de Pury. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . July 22, 2010. Retrieved May 17, 2017 .

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, pp. 5–6. in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, pp. 4, 7–9. in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Dominique Frey: Between "Postman" and "Mediator" , pp. 30–32.

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 23 in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Dominique Frey: Between "Postman" and "Mediator". Swiss protective power activities for Great Britain and Germany in World War II . Verlag Traugott Bautz, Nordhausen 2006, ISBN 3-88309-381-5 , p. 20 .

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 24 in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 16. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the department for foreign interests, p. 28 in the database Dodis of the diplomatic documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the department for foreign interests, pp. 27-29. in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the department for foreign interests, pp. 33–34. in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Swiss Consular Regulations of October 26, 1923 (BS 1 346). Retrieved May 16, 2017 .

- ↑ Accountability report of the department for foreign interests, p. 39. in the Dodis database of diplomatic documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Dominique Frey: Between "Postman" and "Mediator" , foreword.

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 6. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ^ Online official publications SFA: Report of the Swiss Federal Council on its management in 1941 . ( April 21, 1942). In: Annual reports of the Federal Council . Volume 87, 1942, pp. 1–356, here: pp. 109–115.

- ^ Online official publications SFA: Report of the Swiss Federal Council on its management in 1942 . ( April 20, 1943). In: Annual reports of the Federal Council . Volume 88, 1943, pp. 1-426, here: pp. 86-90, 103-111.

- ^ Online official publications SFA: Report of the Swiss Federal Council on its management in 1943 . ( April 28, 1944). In: Annual reports of the Federal Council . Volume 89, 1944, pp. 1-424, here: pp. 129-135.

- ^ Online official publications SFA: Report of the Swiss Federal Council on its management in 1944 . ( From March 29, 1945). In: Annual reports of the Federal Council . Volume 90, 1945, pp. 1-408, here: pp. 96-105.

- ^ Online official publications SFA: Report of the Swiss Federal Council on its management in 1945 . ( April 17, 1946). In: Annual reports of the Federal Council . Volume 91, 1946, pp. 1-499, here: pp. 134-146.

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 33. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ^ Dominique Frey: Between "Postman" and "Mediator" , pp. 56–58.

- ↑ Accountability report of the department for foreign interests, p. 34. in the Dodis database of diplomatic documents of Switzerland

- ^ Annual report of the department for foreign interests, pp. 34–35, 47–50. in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 38. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the department for foreign interests, p. 46. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ^ Online official publications SFA: Message from the Federal Council to the Federal Assembly regarding the approval of the two agreements concluded in Geneva on July 27, 1929 to improve the lot of the wounded and sick in the armies and on the treatment of prisoners of war . In: Federal Gazette . Volume 2, No. 37, 1930, accessed on May 16, 2017, pp. 253-345, here p. 329.

- ↑ Accountability report of the department for foreign interests, pp. 38–39. in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Dominique Frey: Between "Postman" and "Mediator" , pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 40. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ annual report of the department for foreign interests 41. in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ^ Rolf Stücheli: Carl Lutz. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . February 6, 2018 , accessed July 8, 2019 .

- ↑ Accountability report of the department for foreign interests, pp. 46–47. in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Dominique Frey: Between "Postman" and "Mediator" , pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 44. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Dominique Frey: Between "Postman" and "Mediator" , p. 71.

- ^ Dominique Frey, Between "Postman" and "Mediator" , pp. 25–26, 103–106.

- ↑ Accountability report of the department for foreign interests, pp. 16-17. in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 18. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the department for foreign interests, pp. 17-18. in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the department for foreign interests, pp. 9-10. in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 44. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 44. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the department for foreign interests, p. 45. in the Dodis database of diplomatic documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the department for foreign interests, pp. 29, 50. in the Dodis database of diplomatic documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 51. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 52. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- ↑ Accountability report of the Department for Foreign Interests, p. 52. in the Dodis database of Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland