Solar energy in China

The solar energy in China has experienced a huge boom in recent years. China is the largest producer of solar technology and, since 2013, has also been the country where the most solar systems are installed. The country owns a quarter of the world's solar capacity and six of the ten largest manufacturers of solar modules are from China. The world's leading manufacturer of solar modules is currently the Chinese company JinkoSolar , which has a global market share of around 10%. With the Tengger Desert Solar Park , China also operates what is currently the largest solar park with a total output of around 1547 megawatts . In 2017, solar energy provided around 1% of China's energy needs .

history

China's solar industry has gone through three different phases in its development. In the early stages, China focused on large-scale production of solar technology. China then began to install this solar technology in China itself. China is now expanding its research into further development and installation in order to reduce costs.

The development of photovoltaic technology in China began in 1958, but was not industrialized until the 1980s. When China entered the solar market in the 2000s, it initially produced almost exclusively solar modules for export. Due to the sharp increase in demand for photovoltaic systems in European countries since 2004, photovoltaic production in China experienced very strong growth. Mass production in China and the subsequent drop in prices in the photovoltaic market led to numerous bankruptcies among western manufacturers who were unable to withstand the price competition. In Germany , too , many manufacturers had to file for bankruptcy, including Solar Millennium , Solarhybrid and Q-Cells . Siemens dissolved its solar thermal and photovoltaic divisions in 2012, and shortly afterwards Bosch withdrew from the photovoltaic market with losses totaling 2.4 billion euros.

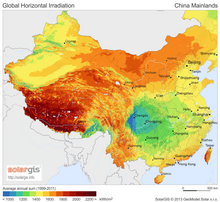

Originally, the high cost of photovoltaic systems prevented the Chinese domestic market from growing . The single market for photovoltaic systems has mostly focused on electrifying remote rural areas and was limited to a small number of solar systems. The first Chinese solar park with a connection to the power grid was put into operation in 2008 in the desert region of the northwestern province of Gansu .

After the global financial crisis , many governments cut subsidies for solar energy and China's solar industry faced the problem of massive overcapacity . For this reason, the government began to use state incentives to strengthen the development of the domestic market in order to prevent a crisis in the Chinese solar industry. In addition, since 2011 the business of Chinese producers has been weakened by anti- dumping measures by the United States and the EU . As a result of these developments, government subsidies have been further increased in order to reduce dependence on foreign markets. In 2011 and 2012 in particular, the government implemented a number of subsidies for the installation of photovoltaic systems , which in the following years led to steady growth in the domestic market. At the end of 2010, China had only installed systems with a total capacity of 800 megawatts, while at the end of 2016, according to official estimates, a total capacity of 76,500 megawatts had already been achieved. China has thus built up more solar capacity within 5 years than Germany has in the last 20 years.

Situation of the Chinese solar industry

In 2017, the Chinese energy sector invested USD 86.5 billion in solar energy alone. This corresponds to an increase of 58% compared to the previous year and is well above the investment volume of the other types of renewable energies . In total, solar systems with a total capacity of 53 gigawatts were installed in China in 2017. The solar energy capacity installed in China in 2017 thus accounts for over half of the capacity installed worldwide. China is far ahead of all other countries when it comes to installing solar power. The largest solar project financed in China in 2017 is the so-called Jiangxi Municipal Poverty Allevation Plant with a planned output of 540 megawatts and an investment volume of around 653 million US dollars.

Due to the cut in subsidies and installation quotas by the Chinese government as well as higher import tariffs for solar products in the USA, a decline in demand for solar systems is generally expected. This falling demand is expected to shrink the margins of Chinese manufacturers and lower the prices of solar modules. Solar module prices are expected to fall by around 35% in 2018 alone. However, it is also expected that these lower prices, particularly in Asia, will lead to a greater diffusion of photovoltaic systems and possibly to a stimulation of the market in 2019 and 2020. The lower prices in China are already making it possible to install more and more photovoltaic systems in different locations such as rooftops or industrial parks. Such smaller systems are not affected by the Chinese government's quotas for large solar projects. This means that more and more energy consumers are starting to use solar power to cover their energy needs without government subsidies. As early as 2017, small photovoltaic systems contributed around a third to the newly installed solar capacity.

An increasing problem of solar power plants in China is the lack of consumption of the energy produced. In some cases, the operators of the solar power plants have to regulate over 30% of the possible energy production. This problem is also caused by the geographical concentration of solar systems in certain provinces where the electricity grid is outdated and there is a lack of storage facilities for excess electricity.

Overall, however, it is expected that China will remain the largest producer as well as the largest market for solar products in the coming years and will continue to have a significant influence on the global solar industry.

Photovoltaics

China is the global center for the production of photovoltaic products. Chinese companies dominate all areas of the value chain from the production of solar silicon to photovoltaic modules. Seven out of ten photovoltaic modules installed worldwide are now produced by Chinese manufacturers.

Since 2013, China has also been the world's largest market for photovoltaic technology; since 2012, photovoltaic capacities in China have multiplied by a factor of 11. The largest markets for photovoltaic technology within China in 2016 were the provinces of Xinjiang, Shandong and Henan. Photovoltaic technology is used in China in the following five areas: off-grid photovoltaic systems in rural areas, off-grid photovoltaic systems for certain industries such as telecommunications or meteorology , photovoltaic systems for commercial products such as flashlights or chargers, and for the power grid connected photovoltaic power plants. It is estimated that China will increase its photovoltaic capacities by over 130 gigawatts between 2017 and 2022, although this threshold may be reached much earlier given the rapid growth.

Solar thermal power plants

China wants to push ahead with the construction of solar thermal power plants and in its 13th five-year plan stipulated that solar thermal power plants with an output of around 10 gigawatts should be installed by 2020. The technology for solar thermal power plants is mentioned by the Ministry of Science and Technology in the document Summary of the national mid & long-term science and technology development plan (2006–2020) as an important field of research. In 2016, China achieved the first 10 megawatts of solar capacity in the field of solar thermal power plants. In the meantime, large solar projects in the field of solar thermal power plants are being implemented in China, for example the construction of a solar thermal power plant with an output of 200 megawatts and an investment volume of around 575 million US dollars was announced in 2017. In contrast to the photovoltaic industry, China has not taken a leading role in the field of solar thermal power plants, most developments in the field of solar thermal power plants have taken place in the USA, Spain and North Africa .

Solar water heating and heating systems

China is the world's largest market for solar water heating and heating systems . Despite falling demand, the Chinese market with installed capacities of around 27.7 gigawatts exceeded the world's second largest market, Turkey, by a factor of 19 in 2016. Chinese manufacturers are increasingly trying to meet the decreasing demand by developing new areas of application, such as drying Catch agricultural products with the help of solar technology. Overall, the Chinese market is developing from small private systems to larger, centralized systems for apartment buildings or entire residential complexes. In Shandong Province , subsidies were announced in 2016 for centralized solar heating systems for public buildings such as schools and hospitals.

Solar energy in the 13th five-year plan

In the People's Republic of China's 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020) it was determined that by 2020 China should cover around 15% of its energy needs from non- fossil energy sources . Overall, the capacity of renewable energy sources is to be increased to around 680 gigawatts. In addition, the problem of insufficient consumption of electricity generated from renewable sources is to be resolved. However, the capacity targets for photovoltaic systems were reduced from 150 gigawatts in a first draft of the plan to 110 gigawatts. In addition, the current five-year plan, in contrast to the 12th five-year plan, focuses less on the construction of large solar power plants, but rather on the spread of small and private solar systems. The 13th five-year plan also contains measures to restructure research and development in the field of solar technology. These measures are intended to ensure that China has a lead in terms of major technological advances that have not yet been achieved despite efforts in the field of solar technology in the past 15 years.

In addition to the overarching 13th five-year plan, a large number of more detailed five-year plans have been published for specific industries and sectors. In December 2016, such a plan for the development of solar energy in China was published. In this detailed plan it was stipulated, among other things, that by 2020 China should produce solar cells in the field of crystalline silicon technology with an efficiency of 23%.

State control

The development of the solar industry in China, and particularly the development of the photovoltaic sector, is closely related to the Chinese government's incentive programs.

Among the first government programs were the so-called Brightness and Township Electrification Programs , which made a significant contribution to the development of the photovoltaic industry in the late 1990s to the early 2000s. The aim of these programs was to install photovoltaic and wind power systems to provide electricity to around 23 million Chinese without access to electricity. In 2009, the Chinese government implemented the Rooftop Subsidy Program and the Golden Sun Demonstration Program to specifically strengthen the Chinese domestic market for photovoltaic technology. With the help of these programs, the dependency of Chinese producers on foreign markets should be reduced, since during this period there were increased trade tensions with the EU and the USA.

Originally, the subsidies for the construction of solar systems were independent of the actual energy production. In the context of the Golden Sun Demonstration Program , too , the amount of subsidies was only based on the amount of capital invested. However, the Chinese government quickly changed this approach, as tying it to investment levels made it easier to abuse subsidies.

In 2011 the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) introduced nationwide electricity price subsidies for the development of photovoltaic systems for the first time. The aim of the Notice on Perfection of Policy Regarding Feed-in Tariff of Power Generated by Solar PV was to further advance the development of the solar industry and to increase the share of solar energy in power generation in China. For this purpose, certain amounts per kilowatt hour have been set with which operators of photovoltaic systems with a connection to the power grid are subsidized. Due to the electricity price subsidies, the development of solar capacities has experienced enormous growth. As a result, Germany's solar capacity was already exceeded in 2015.

In order to be able to continue building up solar capacities, the government wants to increase the efficiency of the capital used for subsidies in the future. For this purpose, for example, the electricity price subsidies and the approval process for solar projects are to be further developed. In addition, new state and private financing options for solar projects are to be created.

In June 2018, the Chinese government decided to lower the subsidies for solar power and the quotas for solar projects. These measures are aimed at slowing the strong growth of the Chinese solar industry. The growth had previously led to a deficit of 15 billion US dollars in funds for solar power subsidies, and the quotas for solar projects had already been reached in the first five months of 2018. The goal of the government is therefore to make the support of the construction more efficient and thus to use the financial resources with greater efficiency. Despite the growing subsidy expenditure, the Chinese regulators have so far only implemented weak measures against the construction of solar power plants outside of the state-mandated quotas. This approach is a sign of growing pressure from the solar industry, which is speculating on a continuation of the subsidies in the coming years.

In March 2018 it was also announced that the Chinese government was planning to establish a new energy ministry. This new ministry is intended to bring together the various government agencies in the field of energy supply and thus simplify the regulation of the energy sector and the implementation of reforms. The new ministry would thus replace the current regulatory authority, National Energy Administration (NEA) , which was established by the National Development & Reform Commission (NDRC) .

See also

further reading

- J. Ball, D. Reicher, X. Sun, C. Pollock: The new solar system: China's evolving solar industry and its implications for competitive solar power in the United States and the world. Stanford University, Stanford 2017. ( www-cdn.law.stanford.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- S. Zhang, Y. He: Analysis on the development and policy of solar PV power in China. In: Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. vol. 21, 2013, pp. 393-401.

- LT Lam, L. Branstetter, IL Azevedo: A sunny future: expert elicitation of China's solar photovoltaic technologies. In: Environmental Research Letters. vol. 13, no. 3, 2018, pp. 1–10. ( iopscience.iop.org , accessed July 3, 2018)

- J. Wang, S. Yang, C. Jiang, YM Zhang, PD Lund: Status and future strategies for Concentrating Solar Power in China. In: Energy Science and Engineering. vol. 5, no. 2, 2017, pp. 100-109. ( onlinelibrary.wiley.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- J. Gosens, T. Kaberger, Y. Wang: China's next renewable energy revolution: goals and mechanisms in the 13th Five Year Plan for energy. In: Energy Science and Engineering. vol. 5, no. 3, 2017, pp. 141–155. ( onlinelibrary.wiley.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

Individual evidence

- ^ C. Dickson: Top Markets Report Renewable Energy. International Trade Administration, Washington, DC 2016, pp. 35–36. ( trade.gov , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ a b c China is rapidly developing is clean-energy technology. In: The Economist. May 15, 2018. ( economist.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ C. Watanabe: China, India lead global solar power expansion. In: Bloomberg. May 21, 2018. ( bloomberg.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ C. Baraniuk: Future energy: China leads world in solar power production. In: BBC News. June 22, 2017. ( bbc.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ A b J. Ball, D. Reicher, X. Sun, C. Pollock: The new solar system: China's evolving solar industry and its implications for competitive solar power in the United States and the world. Stanford University, Stanford 2017, p. 17. ( www-cdn.law.stanford.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ A b c S. Zhang, Y. He: Analysis on the development and policy of solar PV power in China. In: Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. vol. 21, 2013, p. 394.

- ^ J. Ball, D. Reicher, X. Sun, C. Pollock: The new solar system: China's evolving solar industry and its implications for competitive solar power in the United States and the world. Stanford University, Stanford 2017, p. 58. ( www-cdn.law.stanford.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ F. Vorholz: Solar power is red. In: time online. April 12, 2012 ( zeit.de , accessed July 5, 2018)

- ^ P. Guyton: Siemens construction site. In: Der Tagesspiegel. November 24, 2012 ( tagesspiegel.de , accessed July 5, 2018)

- ↑ A. Frese, C. Visser: The solar exit. In: Der Tagesspiegel. March 23, 2013 ( tagesspiegel.de , accessed July 5, 2018)

- ^ A b c S. Zhang, Y. He: Analysis on the development and policy of solar PV power in China. In: Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. vol. 21, 2013, p. 395.

- ^ X. Yang, Y. Song, G. Wang, W. Wang: A comprehensive review on the development of sustainable energy strategy and implementation in China. In: IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy. vol. 1, no. 2, 2010, p. 63. (pp. 57–65)

- ^ J. Ball, D. Reicher, X. Sun, C. Pollock: The new solar system: China's evolving solar industry and its implications for competitive solar power in the United States and the world. Stanford University, Stanford 2017, p. 148. ( www-cdn.law.stanford.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ J. Ball, D. Reicher, X. Sun, C. Pollock: The new solar system: China's evolving solar industry and its implications for competitive solar power in the United States and the world. Stanford University, Stanford 2017, p. 19. ( www-cdn.law.stanford.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ A. McCrone: Global trends in renewable energy investment 2018. Frankfurt School of Finance & Management, Frankfurt 2018, p. 27. ( fs-unep-centre.org , accessed on July 3, 2018)

- ↑ D. Wenjuan, Q. Ye: Utility of renewable energy in China's low-carbon transition. The Brookings Institution, May 18, 2018. ( brookings.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ BP (no date): Solar Energy. ( bp.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ A. McCrone: Global trends in renewable energy investment 2018. Frankfurt School of Finance & Management, Frankfurt 2018, p. 28. ( fs-unep-centre.org , accessed on July 3, 2018)

- ↑ D. Fickling: Chinese burn will only make the solar industry stronger. Bloomberg, June 5, 2018. ( bloomberg.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ A. McCrone: Global trends in renewable energy investment 2018. Frankfurt School of Finance & Management, Frankfurt 2018, p. 28. ( fs-unep-centre.org , accessed on July 3, 2018)

- ↑ C. Baraniuk: Future energy: China leads world in solar power production. In: BBC News. June 22, 2017. ( bbc.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ J. Ball, D. Reicher, X. Sun, C. Pollock: The new solar system: China's evolving solar industry and its implications for competitive solar power in the United States and the world. Stanford University, Stanford 2017, pp. 19-20. ( www-cdn.law.stanford.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ J. Ball, D. Reicher, X. Sun, C. Pollock: The new solar system: China's evolving solar industry and its implications for competitive solar power in the United States and the world. Stanford University, Stanford 2017, pp. 110, 147. ( www-cdn.law.stanford.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ LT Lam, L. Branstetter, IL Azevedo: A sunny future: expert elicitation of China's solar photovoltaic technologies. In: Environmental Research Letters. vol. 13, no. 3, 2018, p. 1. ( iopscience.iop.org , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ International Energy Agency: PVPS Report Snapshot of Global PV 1992–2013. 2014, p. 5. ( iea-pvps.org , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ a b REN21 2017, Renewables 2017 global status report. P. 64. ( solarthermalworld.org , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ A. Jäger-Waldau: PV status report 2017. EU Commission, Brussels 2017, p. 24. ( publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu , accessed on July 3, 2018)

- ^ C. Dickson: Top Markets Report Renewable Energy. International Trade Administration, Washington, DC 2016, p. 36. ( trade.gov , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ J. Wang, S. Yang, C. Jiang, YM Zhang, PD Lund: Status and future strategies for Concentrating Solar Power in China. In: Energy Science and Engineering. 2017, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 2017, p. 104. ( onlinelibrary.wiley.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ REN21 2017, Renewables 2017 global status report. P. 72. ( solarthermalworld.org , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ D. Williams: $ 575m solar power project set for China. In: Power Engineering International. June 16, 2017. ( powerengineeringint.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ J. Wang, S. Yang, C. Jiang, YM Zhang, PD Lund: Status and future strategies for Concentrating Solar Power in China. In: Energy Science and Engineering. 2017, vol. 5, no. 2 2017, p. 100. ( onlinelibrary.wiley.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ REN21 2017, Renewables 2017 global status report. Pp. 75, 77, 80. ( solarthermalworld.org , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ International Energy Agency: China 13th Renewable Energy Development Five Year Plan (2016–2020). 2018. ( iea.org , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ J. Goshen, T. Kåberger, Y. Wang: China's next renewable energy revolution: goals and mechanisms in the 13th Five Year plan for energy. In: Energy Science and Engineering. 2017, vol. 5, no. 3, 2017, p. 146. ( onlinelibrary.wiley.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ J. Ball, D. Reicher, X. Sun, C. Pollock: The new solar system: China's evolving solar industry and its implications for competitive solar power in the United States and the world. Stanford University, Stanford 2017, p. 92. ( www-cdn.law.stanford.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ J. Ball, D. Reicher, X. Sun, C. Pollock: The new solar system: China's evolving solar industry and its implications for competitive solar power in the United States and the world. Stanford University, Stanford 2017, p. 92. ( www-cdn.law.stanford.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ S. Zhang, Y. He: Analysis on the development and policy of solar PV power in China. In: Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. vol. 21, 2013, p. 396.

- ^ J. Ball, D. Reicher, X. Sun, C. Pollock: The new solar system: China's evolving solar industry and its implications for competitive solar power in the United States and the world. Stanford University, Stanford 2017, p. 148. ( www-cdn.law.stanford.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ S. Zhang, Y. He: Analysis on the development and policy of solar PV power in China. In: Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. vol. 21, 2013, pp. 396-397.

- ^ J. Ball, D. Reicher, X. Sun, C. Pollock: The new solar system: China's evolving solar industry and its implications for competitive solar power in the United States and the world. Stanford University, Stanford 2017, p. 149. ( www-cdn.law.stanford.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ J. Ball, D. Reicher, X. Sun, C. Pollock: The new solar system: China's evolving solar industry and its implications for competitive solar power in the United States and the world. Stanford University, Stanford 2017, p. 150. ( www-cdn.law.stanford.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ L. Hook, L. Hornby: China's solar desire dims'. In: Financial Times. June 8, 2018. ( ft.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ R. Rapier: Why did China tap the brakes on its solar program? In: Forbes. June 5, 2018. ( forbes.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ L. Hook, L. Hornby: China's solar desire dims'. In: Financial Times. June 8, 2018. ( ft.com , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ^ J. Ball, D. Reicher, X. Sun, C. Pollock: The new solar system: China's evolving solar industry and its implications for competitive solar power in the United States and the world. Stanford University, Stanford 2017, p. 27. ( www-cdn.law.stanford.edu , accessed July 3, 2018)

- ↑ J. Mason, B Kang Lim: Exclusive: China planst to create energy ministry in government shake-up-sources. In: Reuters. March 8, 2018 ( reuters.com , accessed July 3, 2018)