Deuterocanonical

Deuterocanonical (from ancient Greek δεύτερος [ dɔʏ̯tərɔs ], German 'second' and ancient Greek κανών [ kanoːn ], German 'straight rod' , from Latin canon 'measure' ) is a term used to designate certain writings of the Old Testament (AT), which are regarded by the Catholic Church and partly by the Orthodox Church and the ancient Near Eastern churches as an integral part of the Bible, i.e. are canonical in these churches , but which Judaism and the churches of the Reformation consider apocryphal . In the Protestant area the term apocrypha and in ecumenical cooperation late writings of the Old Testament with almost the same content are common. As protocanonical (from ancient Greek πρῶτος [ proːtɔs ], German 'first' ), on the other hand, the writings of the Old Testament contained in the Jewish and Protestant canons are designated. The deuterocanonical books are supplemented with additional writings of the Orthodox churches as Anaginoskomena (= "readable") refers.

Terms

The terms deutero- and protocanonical go back to Sixtus of Siena (1520–1569), who used them for the first time in the first volume of his Bibliotheca Sancta (Venice 1566). The names allude to the history of the canon development, in which there were doubts about the canonical character of the deutero-canonical writings. Since there were no such doubts about the proto-canonical writings, these were the first to enter the canon, while the deutero-canonicals came second after these doubts had been overcome; in the Latin Church this happened in the 4th century AD.

Shortly before this conceptual formation, Luther moved the deutero-canonical texts into a separate part of the Bible when he translated the Bible, which he called “Apocrypha” because he regarded them as extra-canonical. The term "deuterocanonical" was a reaction to this term, which is inappropriate for Catholics. This has resulted in a range of almost, but not entirely synonymous terms:

- apocryphal

- The adjective describes texts which, according to form, content and - often incorrectly - author's statement, could be biblical texts, but which do not belong to the biblical canon (see article apocryphal ). Since the Bible canon is different in different denominations and traditions, the exact meaning depends on the attitude of the speaker. The word can, but does not have to, also express a disapproval of the origin or the content of the text. Apocryphal texts are also called "Apocrypha" for short.

- The apocrypha

- The term "The Apocrypha" for a clearly delimited group of texts refers to those texts that Luther placed in a separate part of the Bible between the Old and New Testaments when he translated the Bible in order to make it clear that in his judgment they are apocryphal in the sense just mentioned. A content-related disapproval is not associated with this designation. It is a selection from the Old Testament texts of the Septuagint that are not contained in the Tanakh , namely (with one exception) precisely those which are regarded as canonical by the Catholic Church.

- deuterocanonical

- The adjective designates those texts from the above group that belong to the Catholic Bible canon. See the beginning of this section and the definition below.

- Late Old Testament writings

- This term, instead of the denominational “deuterocanonical writings” and “Apocrypha”, comes from an agreement between the German-speaking Bible Societies and Catholic Biblical Works on the occasion of the jointly responsible translation of the Bible into today's German (1982, later renamed Good News Bible ). However, he also makes a statement about the canon, namely that it is about "Scriptures of the Old Testament", that is, the Bible.

The word "deuterocanonical" is also used by Protestant authors, probably in the originally not intended understanding that "belonging to a second, later canon" does not have to mean that one agrees to this canon itself. Because it can be used as an adjective, it is also more handy than the alternatives ("deuterocanonical" instead of "Old Testament late writing").

The last three terms refer to the same texts with the following differences:

- They contain different assessments of membership in the Bible canon, as shown above.

- Especially as far as a separate part of the Bible is concerned, the terms “Apocrypha” and “Late Scriptures of the Old Testament” are predominant.

- Strictly speaking, the prayer of Manasseh belongs to the Apocrypha and the Late Scriptures, but not to the Deuterocanonical scriptures because it does not belong to the Catholic canon. In most contexts it doesn't matter.

definition

The deuterocanonical writings are books or additions to books that were handed down in the Septuagint , but not in the Masoretic text tradition. These books have come down to us in the Greek language, but z. In some cases, Hebrew originals are to be accepted. The time of origin are the last two centuries BC. Therefore they are referred to as "late writings of the Old Testament" in the Good News Bible . They offer valuable insights into the time of Judaism shortly before the emergence of Christianity. Often in these books it is mentioned that people prayed to God - and these prayers are detailed. In most of the Deuterocanonical books, more than ten percent of the content is devoted to such prayer. In contrast, in the Tanach it is only a few percent of the content, and that also applies to the New Testament.

In detail, it concerns the following texts; here “in Protestant Bibles” is to be understood as “in Bibles with a Protestant or ecumenical background, insofar as they contain a section 'Apocrypha' or 'Late Scriptures of the Old Testament'”.

- Deuterocanonical books

- These books are included in Catholic Bibles under the books of the Old Testament, in Protestant Bibles they are in the section "Apocrypha" as an appendix to the Old Testament.

- Deuterocanonical text passages on protocanonical books

- Additions to the book of Daniel

- Additions to the Book of Ester

- These texts are part of the proto-canonical book in Catholic Bibles. In Protestant Bibles they are grouped like books under the Apocrypha, although they cannot all be read continuously, but rather have to be inserted piece by piece at different places in the proto-canonical book.

- Text not found in Catholic Bibles

- This short prayer is classified under the Apocrypha in Protestant Bibles and is not found in Catholic Bibles because it is not recognized as (deutero) canonical.

The remaining parts of the Septuagint that are not in the Jewish and Evangelical canons ( 3rd book of Ezra , 3rd and 4th book of the Maccabees and the Psalms of Solomon ) are also rejected as apocryphal by the Catholic Church . But they can be found occasionally in the canons of the Orthodox or other churches. The individual manuscripts of the Septuagint from the 4th and 5th centuries have different sizes, so one cannot speak of a clear “Septuagint canon”. The Codex Alexandrinus, for example, contains all four Maccabees, the Codex Sinaiticus 1st Maccabees and 4th Maccabees, and the Codex Vaticanus none of these four Maccabees at all.

Church reception

The first Christians had an unbiased relationship with the Septuagint (LXX). Most of the Old Testament quotations in the New Testament come from her . The New Testament quotes several times from texts that cannot be found in the Hebrew Bible ( Tanakh ) - but not in the deuterocanonical books either, e.g. B .: Jude 14 quotes Enoch , and Titus 1:12 quotes a Greek poet (probably Epimenides ). This shows that being cited in this way does not necessarily indicate canonical recognition. “Scripture” is quoted several times without the quotation being clearly assigned (Joh. 7,38, 1.Cor. 2,9; Jak. 4,5). There are about 300 clear references to the Old Testament in the New Testament (not a single one to a deuterocanonical book). Some editions of the New Testament have registers with thousands of parallels; however - as possible, unsafe references - such are not very meaningful. (Such parallels can be found with many texts, although it is unclear whether the later author meant or even knew the earlier text.)

Occasionally the Apostolic Fathers and early Church Fathers quote from Deuterocanonical scriptures. The author of the letter to Barnabas quotes a. a. from the book Jesus Sirach, Polycarp quotes Tobit, the Didache quotes the wisdom of Solomon and Sirach. and the First Letter of Clement quotes wisdom. The emphasis in her quotations is always on some proto-canonical books, namely Isaiah , the Book of Psalms , the Book of the Twelve Prophets and the Pentateuch . The rest of the books are used less frequently, and such occasional references give little certainty about their canonical validity.

Discussions about the canonical recognition of certain books have been conducted by theologians. For the congregations, such demarcations were “border issues”, which they seldom affected, especially in the Old Testament. Because until well into the 4th century the congregations owned only a part of the books of the Old Testament, such as the Pentateuch, Psalter and Isaiah. The question of which Old Testament history books (which they did not have anyway) are canonical and which are not was therefore not so relevant for the churches.

By Melito of Sardis , a detailed list of the books of the Old Testament was first († 190) in Christianity published. He had made inquiries in the Holy Land and came to the conclusion that only the books of the Jewish canon belong to the Old Testament. As a result, a number of - especially Eastern - Church Fathers followed this position with small variations. These included the church fathers who knew Hebrew: Origen, who wrote commentaries on the majority of the biblical books, but not on a single deuterocanonical book, and the influential Jerome . He saw the scriptures not in the Hebrew canon as extra-canonical, but nevertheless included them in his Bible translation, the Vulgate , which was later binding in the Latin Church for several centuries , and also quoted from them, in part as "holy scriptures". He also coined the term "apocryphal": Hieronymus used it to designate the deuterocanonical writings, which can be read "for the edification of the people", even if, in his opinion, they did not belong to the Bible, in contrast to Athanasius before him, who called it used books viewed as heretical that claimed biblical status.

At the end of the 4th century (around 375) a commentary on a deuterocanonical book was written for the first time: Ambrosius of Milan wrote De Tobia . Generally speaking, the Deuterocanonical writings were very much valued in the West. The position of Augustine , who defended her canonicity against Jerome, was decisive . His position was confirmed in a number of African plenary councils in which Augustine attended, beginning with the plenary council at Hippo 393, and in some papal letters.

With this, the discussion about the canon of the Old Testament in the Latin Western Church was basically closed after around AD 400, and until the Reformation, the canon valid today in the Roman Catholic Church was assumed with a few exceptions.

The belief in the canonical nature of deutero-canonical writings later also prevailed in the Eastern churches. They are called "Anaginoskomena" there. However, additional writings of the Septuagint, especially the 3rd Maccabees and 1st Ezra - called 3rd Ezra by Catholic authors - and, in the case of the Ethiopian Church , the books of Enoch and 4th Ezra, which are not contained in the Septuagint, are also included.

reformation

With recourse to Hieronymus, the reformers rejected the canonical status of the deutero-canonical writings. Here the influence of humanism on the reformers made itself felt. The aim was to get ad fontes , i.e. to the original sources, so the Hebrew tradition was rediscovered. Some, like Luther in particular, also followed Jerome in using the term “apocryphal” and their thoroughly positive assessment. So Luther added them - with the prayer of Manasseh - to his translation of the Bible with the heading “Apocrypha: These are books: not kept in the same way as the holy scriptures, and yet useful and easy to read” as an appendix to the Old Testament.

Later the rejection became more consistent, and some of the apocryphal books were no longer included in evangelical translations of the Bible. Some of them are included again in today's Bible translations, but they are critically commented on.

Above all in response to the position of the reformers, the Council of Trent on April 8, 1546, made the canon binding for the Catholic Church - including the Deutorocanonical scriptures. It was also regulated that they are to be regarded as equal to the other books of the Holy Scriptures.

literature

- Otto Kaiser : Outline of the introduction to the canonical and deutero-canonical writings of the Old Testament , 3 volumes; Gütersloher Verlags-Haus, Gütersloh 1992/1994 , ISBN 3-579-00058-6 (Volume 1); ISBN 3-579-00053-5 (Volume 2); ISBN 3-579-00054-3 (Volume 3).

- Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer : The praying people of God before Jesus' first coming. The great importance of prayer in the Deuterocanonicals. In: Heritage and Mission. Benedictine Monthly No. 76 (2000), pp. 149–152.

- Andreas Hahn: Canon Hebraeorum - Canon Ecclesiae: On the deutero-canonical question in the context of the justification of Old Testament script canonicality in more recent Roman Catholic dogmatics . Lit, Munster et al. 2009, ISBN 978-3-643-90013-5 (= Studies on Theology and the Bible , Volume 2, also a dissertation at the Protestant Theological Faculty of Leuven [Leuven, Belgium] 2005).

Footnotes

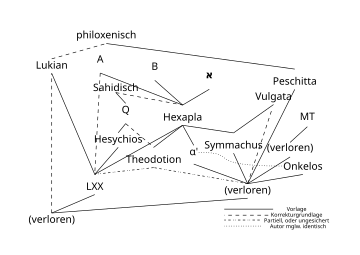

- ↑ In this diagram, LXX means the original version of the Septuagint, consisting of the 5 books of Moses in Greek translation, by the authorship of the rabbis, it has been lost except for rare fragments. In contrast, the Septuagint, which is also called the Greek Old Testament, or other manuscripts that are in the tradition of the Church, such as Lucian, Heysicius, Hexaplar, A, B, א [aleph] etc., are not meant.

- ↑ Also in the 1st century BC The Psalms of Solomon , which originated in BC, are strongly devoted to prayer. - For these observations see Graf-Stuhlhofer: The praying people of God.

- ↑ Barnabas 19: 9 quotes Sirach 4:31; Barnabas 19.2 quotes Sirach 7:32, 33. See Andreas Lindemann, Henning Paulsen (ed.): The Apostolic Fathers. Greek-German parallel edition. JCB Mohr, Tübingen 1992. pp. 69-71.

- ↑ Polycarp 10.2 quotes Tobit 4.10. See Andreas Lindemann, Henning Paulsen (ed.): The Apostolic Fathers. Greek-German parallel edition. JCB Mohr, Tübingen 1992. p. 253.

- ↑ Did. 10.3 cited u. a. Wisdom 1.14, Did. 4.5 quotes sir. 4.31. See Andreas Lindemann, Henning Paulsen (ed.): The Apostolic Fathers. Greek-German parallel edition. JCB Mohr, Tübingen 1992. p. 9 u. P. 15

- ↑ 1. Clem. 27, 4.5 quotes wisdom 9.1 and 12.12. See Andreas Lindemann, Henning Paulsen (ed.): The Apostolic Fathers. Greek-German parallel edition. JCB Mohr, Tübingen 1992. p. 111

- ↑ To this Franz Stuhlhofer : The use of the Bible from Jesus to Euseb. A statistical study of the canon history . R.Brockhaus: Wuppertal 1988, especially Chapters VII and XII.

- ↑ List of Biblical Books of the Ethiopian Church (AT & NT)