Statue of King Chephren (JE 10062)

| Statue of King Chephren | |

|---|---|

|

|

| material | Diorite |

| Dimensions | H. 168 cm; W. 57 cm; D. 96 cm; |

| origin | Giza , valley temple of the Chephren pyramid |

| time | Old Kingdom , 4th Dynasty (ca.2550 BC) |

| place | Cairo , Cairo Egyptian Museum , JE 10062 (CG 14) |

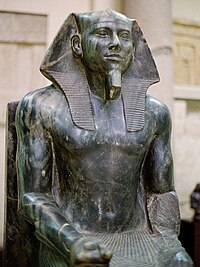

The statue of King Chephren in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo with the inventory number JE 10062 (also CG 14) represents the ancient Egyptian king ( Pharaoh ) Chephren of the 4th Dynasty ( Old Kingdom ), who lived around 2570 to 2530 BC. Ruled. It is a typical portrait of a ruler of this time and is in the context of the monumental architecture of the pyramid period. It originally stood in the valley temple of the Chephren pyramid in Giza , along with 23 similar statues. The dark gray diorite was processed with very high craftsmanship. The Horus Falcon protects the king's head from behind with its wings, but cannot be seen in the front view of the statue. This representation expresses that the king is both under the protection of Horus and is also a manifestation of this God on earth.

Finding circumstances

The statue is one of 23 or 24 statues that originally stood in a large hall of the valley temple of the Chephren pyramid. None of the statues were found in situ , but indentations in the floor indicate where they originally stood. Auguste Mariette found nine of them during excavations in 1860 (Inv.No. CG 9 to CG 17) as well as fragments of a tenth (CG 378) in a shaft within the valley temple. They were buried there for an unknown reason. These statues are now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo . JE 10062 is the best known of them. It is 168 centimeters high and almost completely intact.

None of the statues found in the valley temple are completely identical to the others. According to Gay Robins, this shows an important characteristic of Egyptian art , namely the aversion to unconditional repetition. If one assumes that the statues were not painted, the dark stone must have had a particularly effective effect compared to the temple, which was covered with red granite and white calcite . The straight lines of the statues harmonized with the square pillars and the straight shape of the temple. The statues can be divided into two groups: those with a high-backed throne (which also includes JE 10062) and those with a simple block without a back.

Material and technology

The statue is made of dark gray diorite with white and yellowish veins, which comes from the Nubian Toshka near the 2nd Nile cataract . This shows the far-reaching power that the Egyptian king already had at that time. It has an extremely high quality. The hard stone was hewn with great craftsmanship and finished with a smooth polish that particularly reveals the structure of the stone.

The arms are connected to the body. The beard is attached to the body by a thin web. The space between the lower legs is not very deep. Between the feet there are traces of a drill hole made with a tube drill with the rest of the stone core in it, as well as nails with cuticles. The ears are particularly detailed.

description

The statue represents the fully developed type of the ruler image from the 4th dynasty. The king sits in a majestic posture, looking straight ahead on the throne. The right fist, which encloses a folded cloth, stands on the right thigh. The left hand rests flat on the left thigh. The lower legs almost touch the calves and are parallel.

The king wears the royal Nemes headscarf on his head . Another symbol of the king is the uraeus snake lying flat on the forehead and the king's beard in the form of a braided, artificial chin-beard on the chin. He is also dressed in a loincloth with a barely noticeable indication of the belt and no lion's tail. The folded cloth in the right fist emerges hemispherically at the top and hangs down with two ends on the right knee.

The side parts of the throne are designed as a lion's body. The Horus falcon stands on the throne, its wings spread protectively around the king's head. The Sema-taui ( union of Upper and Lower Egypt ) is shown on both sides of the throne . The sema hieroglyph

|

On the top of the footboard on either side of the feet, the statue is inscribed with a name and title of Chephren in well-trimmed, recessed hieroglyphics.

Although it is a strongly idealized portrait of the ruler, W. and B. Forman also see individual features, for example the pronounced, broad nose, which, although in a less noble form, is found in the alabaster statuette of the king (also in the holdings of the museum in Cairo) .

conservation

The left forearm and lower leg are badly damaged, as well as the right fist and right forearm, some of which were reattached. The first lion's head and a piece of the front legs of the right lion are missing from the throne. The top right corner of the back pillar is also badly damaged.

Interpretations

According to Gay Robins, the fact that the back of the head of the king and the chest of the Horus falcon seem to merge expresses that the king is both under the protection of Horus and is also a manifestation of this god on earth. Although at first glance the statue appears to be that of a person, Zahi Hawass interprets it as a triad: the king represents the late Osiris , the falcon is Horus and the throne on which the king sits is the hieroglyphic symbol for Isis .

The portrait of the ruler is in the context of the monumental architecture of the pyramid period. These graves stand for the divine form and unearthly continued existence of the king. The statues also symbolize royalty carved in stone, which is why the kings were always depicted as athletic men. They turn the earthly king into a superhuman being who can be represented in direct communion with the gods . The statue of Chephren is in their iconography with the beard of the gods and their style him, they caught up into an unapproachable distance, a valid image of divine kingship of the early Old Kingdom .

literature

- Ludwig Borchardt : Statues and statuettes of kings and private individuals in the Cairo Museum. No. 1-1294. Part 1. Text and plates for Nos. 1–380 (= Catalog Général des Antiquités Égyptiennes du Musée du Caire. ). Reichsdruckerei, Berlin 1911, pp. 14–16 ( PDF file; 66.9 MB ); Retrieved from Digital Giza - The Giza Project at Harvard University .

- Zahi Hawass , Sandro Vannini: Inside the Egyptian Museum with Zahi Hawass. American University in Cairo Press, Cairo 2010, ISBN 978-977-416-364-7 .

- Bertha Porter , Rosalind LB Moss , Ethel W. Burney: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings. Volume III: Memphis. Part 1: Abû Rawâsh to Abûṣîr. 2nd edition, revised and expanded by Jaromír Málek . The Clarendon Press / Griffith Institute / Ashmolean Museum , Oxford 1974, pp. 21-23 ( PDF file; 19.5 MB ); Retrieved from The Digital Topographical Bibliography .

- Gay Robins: The Art of Ancient Egypt. 2nd edition, The British Museum Press, London 2008, ISBN 978-0-7141-1982-3 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Bertha Porter, Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. III. Memphis. Oxford 1974, pp. 21-23.

- ^ Bertha Porter, Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. III. Memphis. Oxford 1974, p. 23

- ^ A b Robins: The Art of Ancient Egypt. London 2008, p. 49.

- ^ Robins: The Art of Ancient Egypt. London 2008, p. 49; Michael Höveler-Müller: In the beginning there was Egypt. The history of the Pharaonic high culture from the early days to the end of the New Kingdom approx. 4000-1070 BC. Chr. Mainz 2005, p. 82.

- ↑ a b L. Borchardt: Statues and statuettes. Berlin 1911, p. 15.

- ↑ L. Borchardt: Statues and statuettes. Berlin 1911, p. 14f .; Robins: The Art of Ancient Egypt. London 2008, p. 49ff.

- ^ W. and B. Forman: Egyptian art from the collections of the museum in Cairo. Dausien, Hanau 1968, p. 47.

- ^ Robins: The Art of Ancient Egypt. London 2008, p. 51.

- ^ Zahi Hawass : Inside the Egyptian Museum with Zahi Hawass. Cairo, 2010, p. 22.

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung: Incarnation. On the portrait in the art of the Middle Kingdom. In: Dietrich Wildung (ed.): Egypt 2000 BC. The birth of the individual. Hirmer, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-7774-8540-3 , p. 41.