Subjunction

It's classic

Subjunction ( Latin: subiungere , subordinate ') or conditional (Latin: condicio , condition, condition, condition, constitution') or material implication (Latin: materia , what something consists of 'and implicare , to include') is used in logic called a statement that is made up of two other statements with the junction "If-then", for example the statement "When an electrical current flows, the line heats up".

A careful distinction must be made between the subjunction or material implication - or the conditional - as an object-language link that links two statements to form a new statement on the same language level, and the metalinguistic implication. The metalinguistic implication is a statement about two statements, for example such a statement: “The statement 'It's raining' implies the statement 'The road is wet.' “The connection between subjunction (as a material implication) and metalinguistic implication is that an implication“ The statement 'A' implies the statement 'B' ”can apply if the subjunction“ If A, then B ”applies.

Classic subjunction

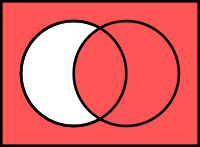

In classical logic , only truth-functional statement combinations are used, that is to say only those in which the truth value of the statement combination depends solely on the truth value of the partial statements. Philo von Megara already understood conditional statements in the same way as a linking table defines the truth-functional subjunction or seq-function using the following truth table ("w" stands for "true"; "f" stands for "false"):

|

In formal languages, a simple arrow is used as a symbol for the junction , especially in the Anglo-Saxon area, based on the Peano-Russell spelling , the curve (“horseshoe”) is used, and occasionally the arrow with two horizontal lines .

In the Polish notation , the capital letter C is used for the material implication , so that the statement “If a, then b” would be written as “Cab”.

Gottlob Frege expresses the conditional “If A, then B” through in his conceptual writing , the first formalization of classical predicate logic .

.

The subjunction corresponds . The negation corresponds .

A peculiarity of the subjunction often leads to misunderstandings, the paradoxes of material implication . So is z. B. the sentence: "If is, then the person is immortal" is true as an overall statement, because the antecedent " " is wrong. From this, however, the truth of the following sentence “Man is immortal” does not follow, because a distinction must be made between the overall statement “If A, then B” and the individual statement B. If the entire subjunction is true, this does not mean that the individual subsequent sentence B is also automatically true.

Dialogic subjunction

In dialogical logic , the subjunction is defined by the following dialogical rules:

| Subjunction | attack | defense |

|---|---|---|

- example

- Someone (the so-called proponent or defender) claims, "If gasoline prices keep rising, car traffic will decrease"; formalized: "Petrol prices continue to rise" (A) "Car traffic is decreasing" (B). If someone (the so-called opponent or attacker) doubts (= "attacks") this claim, he must first prove that the gasoline prices will actually rise. If he succeeds in this, the proponent must now substantiate his claim that car traffic is decreasing. Depending on the chosen (possibly intuitionistic ) framework, a strategy must be developed to determine whether the opponent is first obliged to defend the premise statement A, or whether the defender of the overall statement must defend conclusion B.

literature

- Rüdiger Inhetveen: Logic. A dialogue-oriented introduction . Edition at Gutenbergplatz, Leipzig 2003, ISBN 3-937219-02-1 .

- Wilhelm Kamlah , Paul Lorenzen : Logical Propaedeutics. Preschool of Sensible Speaking . Metzler, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-476-01371-5 .

- Kuno Lorenz , Paul Lorenzen: Dialogical Logic . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1978, ISBN 3-534-06707-X .

- Paul Lorenzen: Textbook of the constructive philosophy of science . Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01784-2 .