Tetonius

| Tetonius | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

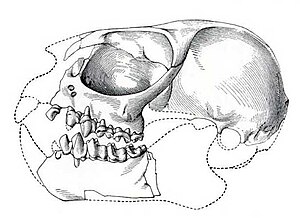

Skull of Tetonius homunculus |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| early Eocene | ||||||||||||

| 55.4 to 50.3 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Tetonius | ||||||||||||

| Matthew , 1915 | ||||||||||||

Tetonius is an extinct genus of four species of primates from the family Omomyidae (tribe Tentoniina within the subfamily Anaptomorphinae) thatwere common in North Americaduring the Eocene . Remains of Tetonius come from sediments in Wyoming and Colorado that are between 55.8 and 48.6 million years old.

Many North American Omomyidae are named for different types of geographic barriers - primarily mountain ranges and rivers - that may be responsible for their diversity. The genus Tetonius is named after the Teton Range , a mountain range that dominates the Wyoming skyline.

anatomy

height

The first descriptor of Tetonius , Edward Drinker Cope , emphasized that the small primate represents a separate branch of the primate evolution , which is essentially different from that of another large group of North American primates from the Eocene, the lemur-like Notharctiden . Tetonius weighed only about ninety grams and was therefore about twenty times smaller than Notharctus tenebrosus . While its tiny size separates Tetonius from most other Eocene primates, according to Cope, the anatomy of the skull and teeth suggested that Tetonius could play a key role in the reconstruction of primate and human evolution. Cope noted that Tetonius extant tarsiers is similar in a number of features to include, for example, the enlarged orbit (though not as large as tarsiers ), and some details of the ear region. At the same time, Cope noted that the upper premolars of Tetonius were similar to those of higher primates ( Anthropoidea ) with their complete lingual cusps (Protoconi).

skull

The most noticeable feature of Tetonius' skull are its large eye sockets, as the first describer Cope recognized when he first examined the specimen. In relation to the length of the skull, the eye sockets of Tetonius are larger than those of diurnal primates living today. In this respect, Tetonius resembles small nocturnal primates like Galago , which could mean that Tetonius was also mainly active at night. Upper jaw fragments from other members of the Omomyidae family , in which the lower edge of the eye socket is additionally preserved, give an indication of the size of the orbit over a broader range of Omomyidae. Although this evidence is less compelling than in the case of Tetonius , enlarged orbits seem to characterize these species too. Most, if not all, of the North American Omomyidae therefore appear to have been mostly active at night . A similar pattern of activity characterizes tarsier , loris , galagos and many lemurs living today . In the higher primates, only the South American night monkeys ( Aotus ) show a similar preference.

Senses

Tetonius' sensory adaptations can be reconstructed on the basis of the natural brain print . Since the skull can be dated to the early Eocene (about 54 million years ago), Tetonius provides the earliest evidence of the brain anatomy of the first primates. Even at this early point in time, Tetonius' brain shows some extended functions that distinguish it from other mammals living at the same time. In Tetonius , the cerebral cortex is enlarged in the posterior and temporal regions of the brain . These are areas related to vision and hearing. At the same time, the olfactory bulb (Bulbus olfactorius) of the brain is reduced in comparison to other mammals occurring at the time, but is still large by the standards of primates living today, especially in comparison with the small olfactory bulbs of tarsier today. The absolute size of Tetonius' brain really isn't that impressive - it reached a meager volume of just 1.5 cubic centimeters. Even if you remember that Tetonius weighed just over ninety grams, the ratio of brain size to body size is below that of primates living today.

denture

The earliest and most primitive fossils of Tetonius from the Bighorn Basin belong to a species called Tetonius matthewi . These small primates have elongated lower jaws , in which the front teeth (from front to back, two incisors , abbreviated I 1 and I 2 , a canine and three premolars, abbreviated as P 2 , P 3 and P 4 ) are very primitive in relation to one another Correspond to the circumstances. In Tetonius matthewi in particular, the I 1 is quite small, the canines are larger than I 2 , P 2 is present and P 3 is supported by two different roots. Over the next 2 million years, these primitive tooth and jaw structures underwent several changes in succession. The entire lower jaw became shorter from front to back and deeper in the area of the chin . This sharp shortening of the jaw leads to a compression of the arrangement of the lower teeth. For example, one of the premolars (P 2 ) was completely lost. The widely spread roots of another premolar (P 3 ) were first compressed and then fused into a single root that supports a much smaller tooth crown. The canines have also been reduced so that they will eventually look similar in size and shape to one of the two incisors (I 2 ). At the same time, the other lower incisor (I 2 ) became hypertrophic and increasingly chisel-shaped. The youngest specimens of the Tetonius line in the Bighorn Basin differ so fundamentally from Tetonius matthewi that they were placed in a separate genus and species called Pseudotetonius ambiguus .

Historical

The collaboration of Edward Drinker Cope and another American paleontologist, Jacob L. Wortman , says a lot about the status of American paleontologists towards the end of the nineteenth century. Both men shared many interests and ambitions, but they came from entirely different worlds. Cope was born into a family of wealthy Quakers in Philadelphia. The family fortunes allowed him to pursue his passion for natural history without the constant search for a permanent position. Wortman, on the other hand, grew up under far more humble circumstances in Oregon. He had to rely on his job to make a living, not the other way around. Both men were brilliant scholars, and their academic achievements reflected their intellect, which was coupled with a high level of personal motivation. Yet their diverse origins meant that their relationship was hierarchical rather than balanced. A man like Cope represented most of the American scientists of the time. Wortman, on the other hand, embodied a new generation of scientists who relied on talent, hard work and, last but not least, a great deal of luck to succeed.

Jacob L. Wortman was a gifted fossil collector, as his later career in paleontology clearly attests. In 1881 he had the advantage in the Bighorn Basin that he found pristine terrain where no one had looked for fossilized remains of prehistoric life before him. But all of these factors can hardly explain the luck Wortman had in finding the oldest primate skull in North America to date. In the more than 120 years of subsequent exploration in the Bighorn Basin - using the latest camping equipment, off-road vehicles, global positioning systems and detailed topographical maps - no second specimen of Tetonius has been uncovered in such excellent condition. Seen in this way, Jacob Wortman's Tetonius skull from 1881 is extraordinary - and in some ways as valuable as the Hope diamond . So it is easy to see why some paleontologists who have spent a large part of their lives professionally searching for fossils in the Bighorn Basin (Willwood Formation) refer to Wortman's Tetonius as the "Jewel of Willwood".

Individual evidence

- ^ Tetonius . In: Paleobiology Database . Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- ^ ED Cope. 1882. An anthropomorphous lemur. The American Naturalist 16: 73-74

- ↑ Radininsky, LB 1977. Brains of early carnivores . Paleobiology 3: 333-349

- ^ Radinsky, LB 1967. The oldest primate endocast. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 27: 385-388

- ^ A b C. Beard, M. Klingler, 2006. The Hunt for the Dawn Monkey: Unearthing the Origins of Monkeys, Apes, and Humans. Univ. of California Pr. ISBN 0-520-24986-0