Mortuary temple of Thutmose III. (Deir el-Bahari)

| Mortuary temple in hieroglyphics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18th dynasty |

Djeser-achet Ḏsr-3ḫ.t Holy (from) the horizon |

||||

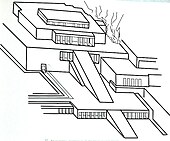

| The space between the mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II (left) and the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut (right) in Deir el-Bahari, where Polish archaeologists found the remains of the mortuary temple of Thutmose III. found. | |||||

The mortuary temple of Thutmose III. (also Djeser-achet ) in Deir el-Bahari is a terrace temple, which the king ( Pharaoh ) Thutmose III. (approx. 1486–1425 BC) was built. The temple was built in the limited space between the mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II and the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut , at an elevated position that towers above the temple.

An inscription describes the temple as the Millennium , but Thutmose III owned it. with Henket-anch already a million year -old house north of the Ramesseum and also the Ach-menu in Karnak was designated as such, which makes it difficult to determine the function. The very poor state of preservation is due to the fact that it has been removed for reuse since the late Ramesside period and the removal of the retaining walls caused a huge landslide.

history

Construction and use

The temple was in the last ten years of Thutmose III. built, probably between the 43rd and 49th year of government. The start of construction coincides with the time of Hatshepsut's dishonor and the associated demolition of their temple. The construction manager was the vizier Rechmire . During the Amarna period, the names and representations of Amun were erased, but later restored. The cult was maintained until the 20th dynasty.

Under Ramses IV. Or Ramses VI. began with the demolition of the temple together with the Mentuhotep temple, presumably to reuse the building material for a larger temple at the lower end of the road. By removing the retaining walls, huge masses of rubble slipped off and triggered a landslide. In the 26th dynasty the ruins served as a burial place.

Discovery and Exploration

As early as 1903, during his excavation work on the mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II , Édouard Naville found the path of the Thutmose temple, although he assumed that it belonged to the Mentuhotep temple. In 1906 Naville discovered the rock sanctuary of the goddess Hathor, which was level with the terrace of the Mentuhotep temple and was possibly connected to it by a staircase. In a campaign by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1912/13, Herbert E. Winlock found the lower end of the path at the fruitland border. He initially assigned this to the Mentuhotep temple, but already recognized 20 years later that it was from Thutmose III. was built.

It was not until 1961/62 that a team of Polish archaeologists headed by Kazimierz Michałowski and later by Jadwiga Lipińska discovered the actual temple complex Djeser-achet of Thutmose III. and this was uncovered in five years of excavation work. Since then, the Polish expedition has been working on the evaluation and reconstruction of the complex found circumstances, including thousands of fragmentary temple elements with inscriptions and reliefs.

architecture

Valley temple

The valley temple was on the land border. It was removed at the time of Ramses IV and reused in the foundations of his temple in el-Birabi, some of which were blocks with the cartouches of Thutmose III. witness.

On the way

About one kilometer east of the mortuary temple, Herbert Winlock discovered in 1912/13 the end of the path at the fruitland border near el-Birabi. The path was bordered on both sides by walls, the longest part of which is a 130 meter long part of the north wall. Two rows of pits were also found, each dug into the rock at six meter intervals. These contained clay and remains of roots. The path was thus decorated with two rows of trees. The southern wall of the access road was completely destroyed, but its width is estimated to be 32.5 meters.

Boat station

Halfway to the main temple, the remains of a barque station were found , a small temple for the cult barque that was carried to the main temple during the valley festival . Apart from a foundation block, no structural elements of this have been preserved in situ, but the foundation pits, which were carved out of the rock, provide information about the size and orientation of the temple. It measured about 11 meters by 16 meters and was oriented precisely on the axes of the access road. A foundation pit was still intact and contained tools, vessels and baskets, among other things.

Main temple

The main temple, located 20 meters high, was reached via a huge 91.5 meter long ramp, which presumably led to a temple front with pillars. Behind it was reached by a Granittor whose walls are still standing, the hypostyle .

The 37.8 meter long and 26.4 meter wide hypostyle is unique in Egyptian architecture and only the festival hall of Thutmose III. in the Ach-menu in Karnak resembles him. In both hypostyles the central colonnade runs transversely to the main axis of the temple and in both it is surrounded by a smaller one, without any apparent relationship between them: the twelve central columns stand out in a basilically elevated position from the lower columns surrounding them on all sides. The walls between the lower ceiling of the surrounding columns and the raised ceiling of the central columns were provided with windows.

The remains of the wall foundations and pillars to the west behind the hypostyle suggest that the temple was here divided into three main parts, each of which had its own processional path through the hall. The central part was undoubtedly dedicated to Amun and contained the hall with four pillars for the sacred barque of Amun, in which it was kept during his visit to the temple, behind it the sacrificial table and finally the sanctuary running along the axis .

The walls of the pillared hall were decorated with scenes from the valley festival, such as the depiction of the barque of Amun, priests, musicians and dancers who took part in the valley festival.

Hathor Chapel

The Hathor Chapel was dedicated to the goddess Hathor or Hathor "Lady of the West Mountain". It was accessed via the north hall of the Mentuhotep temple, but there is evidence that it had no previous building at this point. Édouard Naville found the sanctuary of this temple, which was designed as a cult image cave, still intact. The cult image shows Amenhotep II twice , the son of Thutmose III, who completed the chapel, once as a suckling child while drinking the divine milk from the cow's udder, and once in the form of a round figure, standing in front of the cow. The wall reliefs show next to Thutmose III. Queen Meretre and Meretamun.

- Historical photographs of the Hathor Chapel from 1907

Another small sanctuary of Thutmose III. was the ramp chapel Djeser-menu, the back of which was attached to the ramp to the main temple and was oriented towards the Mentuhotep temple. It was built at the same time as Djeser-achet, but its function has not been clarified, but a connection with the Amun cult is assumed.

More finds

In 1906, Édouard Naville found the faceless top and the torso of a statue of Thutmose III at the Mentuhotep temple. made of crystalline, white stone with blue and black painting. During their excavations in 1967, J. Lipińska discovered the associated face and other fragments of this statue.

The discovery of a headless statue of Senenmut , an official who achieved high dignity under Hatshepsut, possibly shows that this was posthumously taken by Thutmose III. was honored .

meaning

An inscription describes the temple as the Millennium, but Thutmose III owned it. with Henket-anch already a million year-old house north of the Ramesseum and also the Ach-menu in the Karnak Temple was designated as such, which makes it difficult to determine the function. According to Dieter Arnold, it is not a royal mortuary temple, but rather a replacement for the chapels of the gods of the Hatshepsut temple that had been affected by the Hatshepsut persecution, especially for its Amun sanctuary and Hathor sanctuary .

Accordingly, the temple took over the function of the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut as the last stop at the valley festival, during which the cult image of Amun was carried to Deir el-Bahari in a procession of the gods, whereby the temple of Hatshepsut lost its importance. According to Donadoni, however, the honor of accommodating the god overnight in his mortuary temple was due, the current ruling king, which Thutmose III had long done. was and according to his interpretation, only the last stage of the valley festival was moved from the first mortuary temple Henket-anch to Djeser-achit.

literature

(sorted chronologically)

overview

- Dieter Arnold: Deir el-Bahari III. In: Wolfgang Helck [Hrsg.]: Lexikon der Ägyptologie (LÄ). Vol. 1, 1975, col. 1017-1025.

- Dieter Arnold : The temples of Egypt. Apartments for gods, places of worship, architectural monuments. Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-7608-1073-X , pp. 139–40.

- Jadwiga Lipińska : Deir el-Bahri, Tuthmose III temple. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 243-44.

- Dieter Arnold: Lexicon of Egyptian architecture. Bibliographisches Institut, Mannheim 2000, ISBN 3-491-96001-0 , p. 263.

- Gabriele Höber-Kamel: Djeser achit. The memorial temple of Thutmose III. in Deir el-Bahari. In: Kemet 3/2001 , pp. 39-41 and in: Kemet 2/2006 , pp. 23-25.

Monographs

- Édouard Naville : The XIth Dynasty Temple at Deir el-Bahari. Vol. 1 (= Egypt Exploration Fund. [EEF] Vol. 28). London 1907.

- Jadwiga Lipińska: Deir el-Bahari II. The Temple of Thutmose III. Architecture. Varsovie 1977.

- Jadwiga Lipińska: Deir el-Bahari IV. The Temple of Tuthmosis III. Statuary and votive monuments. Varsovie 1984.

Questions of detail

- Herbert E. Winlock : Excavations at Deir el Bahri: 1911-1931. Macmillan, New York NY 1942.

- Jadwiga Lipińska: Names and history of the sanctuaries built by Thutmosis III at Deir el-Bahari. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology (JEA) 53, 1967 , pp. 25-33.

- Rafal Czerner, Stanislaw Medeksza: The New Observations on the Architecture of the Temple of Thutmosis III at Deir el-Bahari. In: Acts 6th International Congress of Egyptologists (ICE), 1992-1993, Vol. II , pp. 119-123.

- Nathalie Beaux: La chapelle d'Hathor de Thoutmosis III à Deir el-Bahari. In: Varia Aegyptiaca (VA). 10: 59-66 (1995).

- Jadwiga Lipińska: Deir el-Bahari, Seven seasons of work, 1978-1987. In: Annales du service des antiquités de l'Égypte (ASAE) 72, 1992–1993 , Le Caire 1998, pp. 45–48.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ J. Lipińska: Deir el-Bahari II. Varsovie 1977, p. 62 and J. Lipińska: Names and history of the sanctuaries built by Thutmosis III at Deir el-Bahari. In: JEA 53, 1967 , pp. 25-33.

- ↑ D. Arnold: The temples of Egypt. Munich / Zurich 1992, pp. 139–140.

- ^ J. Lipińska: Deir el-Bahari II. Varsovie 1977, p. 63 f. and D. Arnold: The Temple of King Mentuhotep of Deir el-Bahari. Architecture and interpretation. Vol. 1, 1974, pp. 68 f.

- ^ A b D. Arnold: Deir el-Bahari III. In: LÄ Vol. I , p. 1022.

- ^ J. Lipińska: Deir el-Bahari II. Varsovie 1977, p. 59 with reference to: H. Winlock, in: Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (BMMA). 1914, pp. 14-15 and H. Winlock: Excavations at Deir el-Bahri 1911-31. New York NY 1942, pp. 4-5.

- ^ J. Lipińska: Deir el-Bahari II. Varsovie 1977.

- ↑ a b cf. J. Lipińska: Deir el-Bahari II. Varsovie 1977, p. 61.

- ↑ J. Lipińska: Deir el-Bahari II. Varsovie 1977, pp. 59-60.

- ^ D. Arnold: Lexicon of Egyptian architecture. Artemis, Zurich 1994, ISBN 3-7608-1099-3 , p. 263 and G. Höber-Kamel: Djeser achit. In: Kemet 3/2001 , p. 40.

- ^ J. Lipińska: Deir el-Bahari II. Varsovie 1977, p. 26 and D. Arnold: Lexicon of Egyptian architecture. Zurich 1994, p. 263.

- ^ J. Lipińska: Deir el-Bahari II. Varsovie 1977, p. 36.

- ↑ G. Höber-Kamel: Djeser achit. In: Kemet 3/2001 , p. 41.

- ^ A b D. Arnold: Deir el-Bahari III. In: LÄ Vol. I, p. 1023.

- ↑ G. Höber-Kamel: Djeser achit. In: Kemet 3/2001 , p. 42.

- ^ J. Lipińska: Deir el-Bahari IV. Varsovie 1977, p. 16 and G. Höber-Kamel: Djeser achit. In: Kemet 3/2001 , p. 40 f.

- ↑ G. Höber-Kamel: Djeser achit. In: Kemet 3/2001 , p. 41 with reference to Sergio Donadoni: Theben. Holy City of the Pharaohs. Hirmer, Munich 2000S, ISBN 3-7774-8550-0 , p. 183.