Trolley problem

The trolley problem is a moral thought experiment recently described by Philippa Foot . The name is derived from the American-English expression for tram . The development of this thought experiment is often wrongly attributed to Hans Welzel , who has since been known in the German-speaking world as the switchman case . The first thoughts on this can already be found in Karl Engisch's habilitation in 1930.

The thought experiment

- Version by Engisch (1930)

- It may be that a switchman, in order to prevent an impending collision, which in all probability will cost a great deal of human life, directs the train in such a way that human lives are also put at risk, but much less than if he were to damage things Let run.

- Version by Welzel (1951)

- A freight train threatens to run into a fully occupied stationary passenger train due to incorrect switch position. A switchman recognizes the danger and diverts the freight train onto a siding so that it races into a group of track workers who all die. How is the criminal liability of the switchman to be assessed?

- Version by Foot (1967)

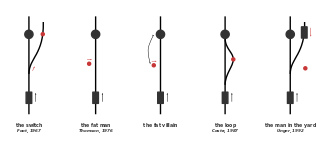

- A tram has gotten out of control and threatens to run over five people. By moving a switch, the tram can be diverted to another track. Unfortunately there is another person there. Can the death of one person be accepted (by turning the switch) in order to save the lives of five people?

Ethical evaluation

Evaluation using ethical intuition

Most people intuitively consider switching the switch to be the right thing to do, which for intuitionists is an indication that this decision is indeed the right one. What then needs to be explained is the ethically relevant difference to other cases in which the rescue of five people at the expense of one human life seems intuitively inadmissible. Judith Jarvis Thomson describes this explanation gap as a trolley problem and contrasts the switchman case with the following thought experiments:

- Organ harvest case ( transplant or organ harvest )

- An excellent surgeon has five patients who all need different organs to stay alive. Unfortunately, there are no donor organs available for this. A healthy young traveler reports for a routine check-up. The doctor determines that his organs fit his five terminally ill patients. Let us assume that if the traveler disappeared, no one would suspect the doctor. Do you think it is right that the doctor cannibalizes the traveler in order to distribute his organs to the five terminally ill patients and thus save their lives?

- Case of the conviction of an innocent person ( Innocent Conviction )

- You are a judge in a legal system in which judges judge the question "guilty" or "not guilty". You have before you a defendant charged with a crime that has caused considerable public outrage. As the trial progresses, you realize that the defendant is innocent. However, the overwhelming majority of the public consider him guilty. As a result, you believe that an acquittal would lead to rioting, in the course of which several people are (innocently) killed and many are injured. Let us assume that the crime must be subject to the death penalty. Are you supposed to convict the accused?

- as well as the variant Fetter Mann ( Fat Man or Bridge ) developed by Thomson

- A tram has gotten out of control and threatens to run over five people. By pushing an uninvolved fat man off a bridge in front of the tram, it can be brought to a stop. Must (by pushing the man) the death of a person caused be to save the lives of five people?

Solutions to the trolley problem

The following objective reasons are discussed in the specialist literature for the fact that the switchman case is different from the cases just mentioned:

- In the case of a switchman, the person who dies after switching the switch is not used as a means to an end .

- In the event of a switchman, an existing hazard is diverted, but no new one is created.

- In the case of switches, the causal chain from action to rescue is no longer than that from action to killing (“causal myopia”).

The following are given as subjective reasons:

- Principle of double action

- Principle of the Triple Effect ( Doctrine of Triple Effect )

- Feelings of the victim

- involuntary grouping ( projective grouping )

- Risk avoidance

- Avoiding uncertainty (i.e., the level of risk is unknown)

- human proximity or distance

Evaluation based on general ethical theories

The trolley problem illustrates elementary differences between utilitarian (or consequentialist ) and deontological theories. A representative of a utilitarian position would save the five lives at the expense of one by changing the switch, since the total number of bad consequences would be fewer.

Within the ethics of duty , the trolley problem illustrates the difference between positive and negative duties. Changing the switch would correspond to the positive duty (mostly classified as weaker) to save others, but would violate the (mostly stronger) negative duty not to kill anyone.

Evaluation in different cultures

Depending on their culture, people can act differently in situations of moral dilemmas. A majority would be more likely to spare children than elders, and humans rather than animals.

Legal evaluation

Germany

In both options of the classic trolley problem, the switchman causes the death of people: by failing to do anything when he does nothing, by doing something actively when he throws the switch.

In German criminal law, the distinction between doing and not doing has significant consequences. Therefore, the two cases must be presented separately below. It is also important that in German criminal law a strict distinction is made between justifying and apologizing (i.e. illegality without individual reproach) of a killing.

Case of omission : In German criminal law, a distinction is made between omissions. On the one hand, there is always a criminal liability that ensures minimum solidarity under the relatively mild Section 323c of the Criminal Code ( failure to provide assistance ). If there is a guarantor , criminal liability according to other norms of the StGB, here manslaughter, § 212 StGB, comes into consideration. A person passing by by chance would have no obligation to guarantee for no apparent reason. Otherwise (e.g. for an instructed switchman on duty), the unlawfulness of the omission is ruled out due to a justifying conflict of duties : In the conflict between an obligation to act and an obligation to cease and desist with regard to legal interests of equal rank, the prevailing opinion must be to refrain from doing so. The inactivity of the guard is therefore justified and not punishable.

Case of action : A justification as an emergency according to § 34 StGB is ruled out - such a quantification would not be compatible with human dignity. The topos of a justifying conflict of duties is only relevant in the event of failure. According to the prevailing view, guilt could be ruled out due to a supra- legal emergency , because: “In such an unusual, almost insoluble conflict of duties, the legal system cannot raise a charge of guilt if the perpetrator makes his decision to the best of his conscience and his rescue purpose under the given circumstances Circumstances is the only means of preventing even greater calamities for legal interests of the highest value. Here, the perpetrator is to be granted impunity in recognition of a supra-legal, excusing state of emergency. ”A minor opinion sees this differently: The supra- legal state of emergency does not apply here because there is no community of danger. It would - in contrast to z. B. shot down an aircraft hijacked by terrorists - previously safe people killed. Part of this inferior opinion would like to meet the perpetrator here via the figure of a mistake in the prohibition (this leads to exclusion of guilt or to a reduction in punishment), because the perpetrator has to decide in a split second.

For further jurisprudence on the supra- legal state of emergency (also referred to as "conflict of obligations" ) see the relevant article.

Austria

In Austria, the view is that human life cannot be quantified as an equal legal asset. It is therefore irrelevant whether action causes a single death or failure to cause a large number of deaths. The offenses relevant in this case, failure to provide assistance ( Section 95 StGB) or murder ( Section 75 StGB), or manslaughter ( Section 76 StGB) are therefore excused in all cases by what is known as the excusatory state of emergency ( Section 10 StGB) and therefore exempt from punishment , but still remain illegal. If, for example, the tram can be stopped by someone throwing an uninvolved person in front of it, then this person may use self-defense ( Section 3 StGB) in order not to be killed himself.

Pop culture and analog use cases

The thought experiment picks up on a problem that also appears in numerous variations in popular culture, for example in the short film Summer Sunday by Fred Breinersdorfer and Sigi Kamml , in which a bridge keeper sacrifices the life of his deaf son to save the passengers of an approaching train. The main question is whether one can accept the death of a few in order to save many, or even have to bring it about for this purpose. The decision problem is varied in the specialist literature by changing the number of people involved or by assigning them special characteristics. The intent of these variations is to explore limits for the moral evaluation of actions and to determine when and on what grounds a particular decision is considered morally justified or reprehensible. The introduction of special conditions is also intended to make it easier to draw analogies to more frequently occurring and controversial decision problems.

Another variant is developing in the programming of self-driving cars . In a study by the University of California , respondents were given the following example: You and another passenger drive in an autonomous vehicle on a single-lane road, walls to the right and left. On the street in front of you, three pedestrians cross the street when it is red. Do you want the controls to crash your car into a wall? The majority of the respondents said that if possible all other road users should have cars with utilitarian controls, but they themselves would prefer to drive a vehicle that protects its passengers under all circumstances. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has developed a moral machine with which you can compare your own decisions with those of the other test subjects online.

Other approaches use virtual reality to assess human behavior in such situations.

literature

- Michael Otsuka : Double Effect, Triple Effect and the Trolley Problem: Squaring the Circle in Looping Cases , in: Utilitas 20/1, March 2008, pp. 92-110

Movie

- Fred Breinersdorfer and Sigi Kamml : Summer Sunday , short film, 2008

- Grant Sputore : I Am Mother , Indie Feature Film, 2019

Individual evidence

- ↑ Philippa Foot: The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of the Double Effect , in: Virtues and Vices , Basil Blackwell, Oxford 1978 (originally published in Oxford Review , number 5, 1967)

- ↑ Hans Welzel: To the emergency problem. In: ZStW. Journal for the entire criminal law science 63 [1951, 1], pp. 47–56.

- ^ Karl Engisch: Investigations into intent and negligence in criminal law . O. Liebermann, Berlin 1930, p. 288 .

- ↑ Would you sacrifice one person to save five others? Der Spiegel (Science) January 28, 2020

- ^ Judith Jarvis Thomson wrote in Killing, Letting Die, and the Trolley Problem : “Why is it that Edward may turn the trolley to save the five, but David may not cut up his healthy specimen [and use his organs] to save his five ? I like to call this the trolley problem, in honor of Mrs. Foot's example. "

- ^ Judith Jarvis Thomson, The Trolley Problem, 94 Yale Law Journal 1395-1415 (1985) wording: "A brilliant transplant surgeon has five patients, each in need of a different organ, each of whom will die without that organ. Unfortunately, there are no organs available to perform any of these five transplant operations. A healthy young traveler, just passing through the city the doctor works in, comes in for a routine checkup. In the course of doing the checkup, the doctor discovers that his organs are compatible with all five of his dying patients. Suppose further that if the young man were to disappear, no one would suspect the doctor. Do you support the morality of the doctor to kill that tourist and provide his healthy organs to those five dying persons and save their lives? "

- ↑ Here in a version by Michael Huemer: http://edition.leske.biz/waffen2/huemer_guncontrol_split-5.html#beispiel4 Philippa Foot wrote in The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of the Double Effect : “Suppose that a judge or Magistrate is faced with rioters demanding that a culprit be found for a certain crime and threatening otherwise to take their own bloody revenge on a particular section of the community. The real culprit being unknown, the judge sees himself as able to prevent the bloodshed only by framing some innocent person and having him executed. "

- ↑ Judith Jarvis Thomson: Killing, Letting Die, and the Trolley Problem , in: The Monist 59, 1976, 204-17 (English)

- ↑ Stijn Bruers, Johan Braeckman: A Review and Systematization of the Trolley Problem , in: Philosophia 42 (2), 2014, pp. 251-269

- ↑ Trolley problem and machine ethics: 82 percent of Germans would sacrifice individual people. Retrieved January 24, 2020 .

- ↑ Kühl, Christian: Criminal Law. General part. Section 18 marginal number 134.

- ↑ BVerfGE 115, 118. available under the judgment of the BVerfG of February 15, 2006 on the Aviation Security Act (1 BvR 357/05)

- ^ Wessels, Johannes / Beulke, Werner ; General Part of Criminal Law, Rn 452.

- ↑ aA Jakobs, AT, § 20 Rn 41, Roxin AT Bd. 1 § 22 Rn 157.

- ↑ Jäger ZStW 115 (2003) p. 780.

- ↑ Legal Commentary Jusline. Retrieved October 18, 2017 .

- ↑ Law of the Supreme Court. Retrieved October 18, 2017 .

- ↑ Patrick Lin: The Ethics of Autonomous Cars . The Atlantic. October 8, 2013.

- ↑ Tim Worstall: When Should Your Driverless Car From Google Be Allowed To Kill You? . Forbes. June 18, 2014.

- ↑ Autonomous Vehicles Need Experimental Ethics: Are We Ready for Utilitarian Cars? . October 13, 2015.

- ^ Emerging Technology From the arXiv: Why Self-Driving Cars Must Be Programmed to Kill . MIT Technology review. October 22, 2015.

- ^ Jean-François Bonnefon, Azim Shariff, Iyad Rahwan: The social dilemma of autonomous vehicles . In: Science . 352, No. 6293, 2016, pp. 1573–1576. doi : 10.1126 / science.aaf2654 . PMID 27339987 .

- ↑ The Moral Machine (MIT)

- ↑ Leon R. Sütfeld, Richard Guest, Peter King, Gordon Pipa: Using Virtual Reality to Assess Ethical Decisions in Road Traffic Scenarios: Applicability of Value-of-life-Based Models and Influences of Time Pressure . In: Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience . . doi : 10.3389 / fnbeh.2017.00122 .

- ↑ Alexander Skulmowski, Andreas Bunge, Kai Kaspar, Gordon Pipa: Forced-choice decision-making in modified trolley dilemma situations: a virtual reality and eye tracking study . In: Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience . December 16, 2014. doi : 10.3389 / fnbeh.2014.00426 .

- ^ Rüdiger Suchsland: Mistrust is part of emancipation. In: Telepolis. August 23, 2019, accessed August 26, 2019 .