Four Sephardic Synagogues (Jerusalem)

The four Sephardic synagogues are located in the Jewish quarter of Jerusalem's old town . Access is from Mishmerot HaKehuma Street. The four synagogues were built one after the other in close proximity to one another and later connected to one another.

Previous buildings

The oldest epigraphic evidence of a synagogue in Jerusalem is the ancient Theodotos inscription (now in the Israel Museum ). According to this, many synagogues in Jerusalem are documented in literature up to the year 70, both in the New Testament (Acts 6: 9) and in rabbinical literature. With the Roman destruction of Jerusalem , the Jewish community life ended and could only be resumed in the early Islamic period.

A letter from Rabbi Moshe Ben-Nachman (acronym Ramban ) to his son reports that he arrived in Jerusalem in 1267 and found only two Jewish families there; after all, a minyan gathered in their house for prayer on the Sabbath . He then set up a ruin as a synagogue by furnishing the building with Torah scrolls from Samaria . This building is described in the letter as follows: “a building in ruins with a beautiful dome supported by marble columns; we took it as a house of prayer, because the city is a field of rubble, and whoever wants to take possession of a ruin can do so. ”However, the authenticity of the letter, as with other letters ascribed to the Ramban, is questionable.

The house of God, now known as the Ramban Synagogue, was used as a permanent temporary facility by the city's Jews as a religious center for centuries . In the 14th century, however, a mosque had already been built directly adjacent to the Ramban Synagogue, and in 1473/74 the Jewish community was asked to close its synagogue in order to improve access to the mosque. The synagogue community appealed to Sultan Kait-Bay , who confirmed their right to the property in 1474/75. Nevertheless, facts were created by the Jerusalem Muslims and the synagogue was illegally torn down. Kait-Bay had those responsible severely punished. But the synagogue was not rebuilt until 1523 and was used for Jewish worship until 1566. In that year the Ottoman governor ordered the synagogue to be closed. A company that produced grape syrup moved into the building. Under the name of al-Maragha , this company existed until 1852.

History of the community

In Ottoman times, the Jewish inhabitants of Jerusalem were organized as an ethnic community ( taifa ), which was divided into several subgroups: the families of Hispanic-Portuguese origin, the Maghrebians from North Africa, the Romaniots from the former Byzantine Empire, the long-established Mustaaribun, the Had adopted the way of life and culture of the Arab population, as well as a few Ashkenazi families. The 16th and early 17th centuries brought a continuous deterioration in living conditions, which was expressed in the loss of the Ramban synagogue. Around 300 Jewish families lived in the city at the end of the 17th century.

- Jaakov Chagiz, who came from Fez (known as an opponent of Shabbtai Zvi ), immigrated to Jerusalem via Italy and Thessaloniki in 1620. in Livorno he collected donations for the establishment of a yeshiva in Jerusalem. He was the first director of this Talmud school, which was called Beit Jaakov after him.

- Rabbi Chaim Ben Attar immigrated to Jerusalem from Morocco in 1742 and founded a synagogue and a house of teaching.

In Constantinople, the capital, a committee was founded in 1724 to support the Jewish community of Jerusalem; the consequence of this was that the Jerusalem community could only practice limited self-government in the 18th century. With the decline of the Ottoman Empire, support from the mother church in Constantinople also declined. The Sephardic community in Jerusalem, which had a high proportion of Talmudic scholars who needed some kind of scholarship to make a living, then turned to the communities in the diaspora for help and was supported in particular from Livorno and Amsterdam.

Building history

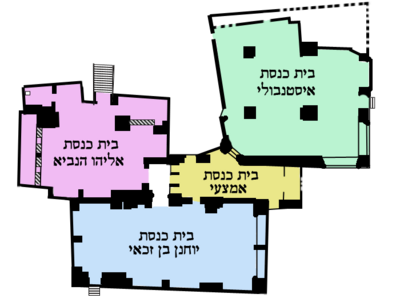

The Sephardic Jews built their new center south of the old synagogue. The Jochanan ben Sakkai Synagogue and the Elijahu-ha-Navi Synagogue are mentioned in the report of an anonymous Jewish traveler in 1625 and are therefore probably the oldest prayer rooms. As the Jewish community grew, the Middle Synagogue (also known as the Emza'i Synagogue) was created in the mid-18th century by converting the women's synagogue or a courtyard into it. The last to be added was the simple and large Istanbuli Synagogue, which was used by immigrants from Asia Minor, but also Ashkenazim (until the Churva Synagogue was built ) and Maghrebians for their services. The Ottoman authorities forbade all renovations, so that the synagogue ensemble fell into disrepair in the 18th century. In 1835 the Sephardic community received permission from the Governor of the Holy Land, Ibrahim Pasha , to renovate the four synagogues. The dilapidated walls were partially torn down and a four-part church was built, which was now called the Jochanan ben Sakkai Synagogue. It became the center of the spiritual and cultural life of Jerusalem's Sephardic community.

During the Palestine War, all four synagogues served as refuge for the residents of the Jewish quarter of Jerusalem's old city. After Jordan conquered the old city of Jerusalem, the four synagogues were devastated and profaned. From then on they served as stables. After the reconquest of East Jerusalem by the Israelis in 1967 in the Six Day War , the synagogues were found in a desolate state. The four synagogues were restored at great expense and re-inaugurated in 1972. Instead of the destroyed interior decoration, many cult objects from Italian synagogues, which were destroyed in World War II, have been decorating the interiors.

The individual synagogues

There are inaccurate and varied information about when the individual synagogues were built:

- Jochanan ben Sakkai Synagogue: 1606–16

- Elijahu-ha-Navi Synagogue: 1606–1610, 1570

- Emza'i Synagogue: 1702-20

- Istanbuli Synagogue: around 1740

Jochanan ben Sakkai Synagogue

The name of the most important of the four synagogues preserves the memory of Jochanan ben Sakkai , whose house of teaching is said to have been located here before the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in AD 70. The Jochanan ben Sakkai Synagogue was the official residence of the Rishon le-Tzion, the representative of the Jews of Palestine to the Ottoman authorities. A hall with three groin vaults rises on a trapezoidal floor plan . In the center of the room is the Bima , the place for the Torah reading; the neo-Gothic Torah shrine is on the east wall.

A domed room rises on a roughly rectangular base. The Torah shrine in the northeast comes from Livorno . In the northwest corner, a staircase leads down to the grotto of the prophet Elijah , where his chair is shown. According to legend, the prophet Elijah is said to have added to the number of worshipers on Yom Kippur , so that a minyan met on this high holiday .

Emza'i Synagogue

The Middle Synagogue is a long rectangular room with groin vaults. It is used by the Mitnagdim as a place of prayer.

Istanbuli Synagogue

This youngest, largest and most modest synagogue was built around 1740. A domed building with a Torah shrine rises on an irregular floor plan in the northeast. The Bema with its painted wooden columns comes from the Italian Pesaro , while the other cult objects were brought here from the synagogue of Ancona .

Reason for the low location

There are various assumptions as to why the floor of the synagogues is several meters lower than street level:

- Because the street level has risen since the late 16th century, so that a floor that was at ground level at the time of construction is now in a pit.

- Because a Muslim law forbade the dhimmi (Jews and Christians) to build their houses higher than the Muslims and the builders of the synagogue still wanted to create the experience of a large room.

- Because Psalm 130 (“From the depths, O Lord, I call you”) was understood to mean that a synagogue, unlike a temple, is not a building to be ascended to, but a modest house of prayer.

literature

- Alisa Meyuḥas Ginio: Between Sepharad and Jerusalem: History, Identity and Memory of the Sephardim . Brill, Leiden / Boston 2015. ISBN 978-9004-27948-3 .

- Max Küchler : Jerusalem: A Handbook and Study Guide to the Holy City . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, pp. 595–597.

Web links

- The four Sephardic synagogues ( Memento of April 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) at rova-yehudi.org

- The Four Sephardic Synagogues , online at: jerusalem.com/articles / ... ( Memento from June 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jonathan J. Price: Synagogue building inscription of Theodotos in Greek, 1 c. BCE-1 c. CE. In: Hannah M. Cotton et al. (Ed.): Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae / Palaestinae . Vol. 1: Jerusalem , part 1. De Gruyter, Berlin 2010, pp. 53–56.

- ↑ a b c d Quoted from: Denys Pringle: The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem : Volume 3, The City of Jerusalem . Cambridge University Press, New York 2007, p. 321.

- ^ Norman Roth: Art. Synagogues. In: Ders., Medieval Jewish Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge, New York / London 2003, p. 622.

- ↑ Alisa Meyuḥas Ginio: Between Sepharad and Jerusalem: History, Identity and Memory of the Sephardim , Leiden / Boston 2015, p. 67f.

- ↑ Alisa Meyuḥas Ginio: Between Sepharad and Jerusalem: History, Identity and Memory of the Sephardim , Leiden / Boston 2015, pp. 68–72.

- ^ A b Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A manual and study travel guide to the Holy City . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, p. 595.

- ↑ a b c d The Sephardi Synagogues , online at: 193.188.73.41/monuments / ... (a project of the Harvard University Graduate School of Design Center for Urban Development Studies and Royal Scientific Society - Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Building Research Center )

- ↑ Eliyahu Hanavi (Elijah) Synagogue , online at: jerusalem.com / ... ( Memento from June 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A manual and study travel guide to the Holy City . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, p. 595f.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A manual and study travel guide to the Holy City . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, p. 596.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A manual and study travel guide to the Holy City . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, p. 596f.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A manual and study travel guide to the Holy City . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, p. 597.

- ↑ Joe Yudin: Off the Beaten Track: Yochanan Ben Zakkai . In: The Jerusalem Post , January 5, 2012.

Coordinates: 31 ° 46 ′ 29.1 ″ N , 35 ° 13 ′ 53.4 ″ E