Westphalian monitor

| Westphalian monitor | |

|---|---|

|

|

| description | Official government gazette |

| language | French , German |

| First edition | December 22, 1807 |

| attitude | October 31, 1813 |

| Frequency of publication | Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays |

| Editor-in-chief | Johann Karl Adam Murhard |

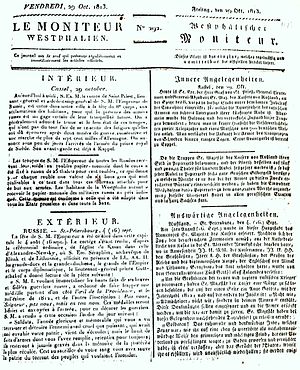

The Westphalian Moniteur. Officielle Zeitung ( French Le Moniteur Westphalien. Gazette Officielle ) was the official government newspaper of the Kingdom of Westphalia with a publishing location in Kassel . It was published between December 22, 1807 and October 31, 1813 as a bilingual print medium in German and French.

context

Newspaper in Napoleonic France

Napoleon Bonaparte recognized early on the importance of the press as a medium that he specifically used to exert political influence. During his Italian campaign, for example, he financed two newspapers to influence the soldiers: the Courrier de l'armée d'Italie ou le Patriote francais à Milan , which dealt with the military campaign in Italy, and La France de l'armée d'Italie who took up domestic political issues. Around 1800 Napoleon controlled almost all print media in Paris, but in 1811 all others were banned by decree with the exception of a few state-affiliated newspapers such as the Gazette nationale ou le Moniteur universel (from 1811 only Le Moniteur universel ).

Planning a Westphalian newspaper

The publication of a Westphalian newspaper was proposed to King Jérôme Bonaparte by Justice Minister Joseph Jérôme Siméon and Finance Minister Jacques Claude Beugnot and implemented by them. In doing so, the Westphalian Moniteur should specifically follow the French model of media influence.

The first editor was the French Jacques de Norvins, who from December 1807 initially held the post of Provisional Secretary General of the Council of State. Other editors of the Westphalian Moniteurs were among others from 1808 the brothers Friedrich Wilhelm August and Johann Karl Adam Murhard from Kassel; Friedrich Murhard was the main editor from 1809 to 1813.

The first edition of the Moniteur appeared on December 22nd, 1807, in which, among other things, the constitution of the Kingdom of Westphalia was published. From January 3, 1808, the newspaper was published under the name Westphälischer Moniteur .

In addition to the Westphalian Moniteur, there were some periodical publications, for example the annals of the Kingdom of Westphalia and Westphalia under Hieronymus Napoleon I (edited by Georg Hassel and Karl Murhard)

Form of the Westphalian Moniteurs

The Westphälische Moniteur followed a recurring formal structure. The title page was divided into internal affairs and external affairs ( interior and exterior ), with the left column containing the original French text and the right column a German translation. The newspaper was thus involved in a policy of bilingualism that also applied to other areas of the state. For example, at the administrative level, the prefectures became the interface for the language ordinance, as they corresponded with the ministries in French and with the lower authorities in German. The newspaper was always published on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, with delivery being post free. The print run at times reached 1500 copies, which were produced in the orphanage printing house in Kassel in mostly four-page large-folio format.

Content of the Westphalian Moniteur

In terms of content, the Westphalian Moniteur covered a variety of topics. This included the publication of decrees, appointments of prefects, cabinet members, civil servants, councilors of state and senior military personnel, orders of the day to the army, promotions, proclamations, addresses of the Senate and speeches of the councils of state in the assembly of estates. This meant that the government gazette not only played the role of a simple newspaper, especially since it also served to present the Westphalian king and the French emperor.

A positive portrayal of the kingdom, the supposed advantages of which were presented exuberantly, was carried out in particular by the editor Murhard. As a government newspaper, it did not contain anything harmful to the state, so that, for example, the resistance to the newly introduced conscription was hardly echoed in the Westphalian Moniteur and was only mentioned indirectly. However, deserters and refractors were advertised by name in the newspaper to be wanted , and their refusal to conscription and service was subject to high penalties, and in some cases their relatives were also sanctioned. The Dörnberg uprising from 22./23. April 1809 found its way into the Westphalian Moniteur with the decree of April 29, 1809 . In this the penalties for the participants in the uprising were announced, respectively the amnesty conditions .

In the Foreign Affairs section , reports were made on the Empire (France, Italy, Spain), Germany, Poland, England, Prussia, Russia, Bohemia, Sweden, Hungary and, in some cases, the USA. A propaganda effect should be achieved in a variety of ways, for example by quoting articles from other (sometimes foreign language) newspapers, as well as real and invented letters on political and military events. Napoleonic policy was also included through army reports, armistice and peace treaties, among other things.

Consequences and efficiency

The establishment of the Westphalian Moniteur had a decisive effect on the press in the Kingdom of Westphalia. The Kassel newspaper Casselsche Policey and Commercienzeitung was transformed on March 3, 1808 into the intelligence paper of the department of Fulda and in October 1810 it became part of the Westphalian Moniteur as a feature section. The other newspapers, for example in Magdeburg , Halle (Saale) and Hamm , were monitored by decree from September 1808 by the General Directorate of the High Police and, unlike the Westphalian Moniteur, had no postal freedom.

The degree of effectiveness of the Westphalian Moniteur on the different social milieus is difficult to assess. An inaccurate and falsifying German translation significantly diminished the propagandistic goal and led parts of the population to think critically by comparing the French original text and the German translation in order to find discrepancies.

literature

- Royal decree of December 7, 1807, which decreed the publication of the constitution of the Kingdom of Westphalia. In: Eckhart G. Franz and Karl Murk (eds.): Constitutions in Hessen 1807–1946. Constitutional texts of the states of the 19th century, the people's state and today's federal state of Hesse. Darmstadt 1998, ISBN 3-88443-034-3 , pp. 21-31.

- Maike Bartsch (Red.): King Lustik? Jérôme Bonaparte and the model state Kingdom of Westphalia. Exhibition catalog, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-7774-3955-6 . In this:

- Armin Ozwar: The old appearance of the new empire. Political change and tradition foundation in the Old Kingdom. (Pp. 155-162).

- Claudie Paye: Vous avez dit Lustik? About languages and language policy in the Kingdom of Westphalia. (Pp. 148-154).

-

Andreas Hedwig , Klaus Malettke , Karl Murk (eds.): Napoleon and the Kingdom of Westphalia. System of rule and model state politics. Marburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7708-1324-7 . In this:

- Ewald Grothe: Fader frills or pioneering reform? On the effect and reception of the Westphalian constitution. (Pp. 125-140).

- Hans-Ulrich Thamer : Power and representation of Napoleonic origin. The symbolic construction of legitimacy in the Napoleonic Empire. (Pp. 39-52).

- Ewald Grothe : The brothers Murhard and Napoleon. To the echo of the French occupation policy in journalism. In: Hessisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte , Volume 54, 2004, ISSN 0073-2001 , pp. 162–175.

- Heinz Gürtler: German Freemasons in the service of Napoleonic politics. The history of Freemasonry in the Kingdom of Westphalia. Berlin 1942 (without ISBN).

- Claudie Paye: “ Can speak French”. Communication in the field of tension between languages and cultures in the Kingdom of Westphalia 1807–1813 . Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-486-71728-0 .

- Volker Petri: The monitor of Westphalia. A medium of Napoleonic communication politics in the years 1808/09. In: Helmut Burmeister (Ed.): King Jérôme and the Reform State of Westphalia. A young monarch and his time in the field of tension between enthusiasm and rejection. Hofgeismar 2006, ISBN 3-925333-47-9 , pp. 187-208.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Thamer: Power and representation of Napoleonic origin. The symbolic construction of legitimacy in the Napoleonic Empire. 2008, p. 41.

- ↑ Thamer: Power and Representation of Napoleonic Origin. The symbolic construction of legitimacy in the Napoleonic Empire. 2008, p. 42.

- ↑ a b c d e f Gürtler: German Freemasons in the service of Napoleonic politics. The history of Freemasonry in the Kingdom of Westphalia. 1942, p. 67.

- ↑ a b Petri: The Moniteur Westphalien. A medium of Napoleonic communication politics in the years 1808/09. 2006, p. 187.

- ↑ Grothe: Fader frills or pioneering reform? On the effect and reception of the Westphalian constitution. 2008, p. 134.

- ^ Gürtler: German Freemasons in the service of Napoleonic politics. The history of Freemasonry in the Kingdom of Westphalia. 1942, p. 68. The constitution as an edited source can be found at: Eckhart G. Franz and Karl Murk (eds.): Constitutions in Hessen 1807–1946. Constitutional texts of the states of the 19th century, the people's state and today's federal state of Hesse. 1998, pp. 21-31.

- ↑ Grothe: Fader frills or pioneering reform? On the effect and reception of the Westphalian constitution. 2008, p. 133 f.

- ↑ Paye: "The French language powerful". Communication in the field of tension between languages and cultures in the Kingdom of Westphalia 1807–1813. 2008, p. 149.

- ↑ a b Petri: The Moniteur Westphalien. A medium of Napoleonic communication politics in the years 1808/09. 2006, p. 188.

- ↑ Grothe: The brothers Murhard and Napoleon. To the echo of the French occupation policy in journalism. 2008, p. 168.

- ↑ Petri: The Moniteur Westphalien. A medium of Napoleonic communication politics in the years 1808/09. 2006, p. 190.

- ↑ Petri: The Moniteur Westphalien. A medium of Napoleonic communication politics in the years 1808/09. 2006, p. 203.

- ↑ Petri: The Moniteur Westphalien. A medium of Napoleonic communication politics in the years 1808/09. 2006, pp. 190-192.

- ↑ Grothe: The brothers Murhard and Napoleon. To the echo of the French occupation policy in journalism. 2008, pp. 169-171.

- ↑ Petri: The Moniteur Westphalien. A medium of Napoleonic communication politics in the years 1808/09. 2006, p. 195.

- ↑ Paye: "The French language powerful". Communication in the field of tension between languages and cultures in the Kingdom of Westphalia 1807–1813. 2013, p. 231.

- ↑ Petri: The Moniteur Westphalien. A medium of Napoleonic communication politics in the years 1808/09. 2006, p. 197.

- ↑ Petri: The Moniteur Westphalien. A medium of Napoleonic communication politics in the years 1808/09. 2006, p. 198.

- ↑ Petri: The Moniteur Westphalien. A medium of Napoleonic communication politics in the years 1808/09. 2006, pp. 198-203.

- ↑ Petri: The Moniteur Westphalien. A medium of Napoleonic communication politics in the years 1808/09. 2006, p. 204.

- ↑ Ozwar: The old appearance of the new empire. Political change and tradition foundation in the Old Kingdom. 2008, p. 156. Ozwar assumes the main recipient is the business and educated middle class. Ibid.

- ↑ Paye: "The French language powerful". Communication in the field of tension between languages and cultures in the Kingdom of Westphalia 1807–1813. 2013, pp. 148–152.