Zimri-Lim

Zimri-Lim was from 1773 to 1759 BC. Chr. ( Middle chronology ), 1709 to 1695 BC Chr. ( Short chronology ), 1677 to 1663 BC BC (ultra-short chronology) last king of Mari , whose domain also included Terqa and large parts of the Syrian steppe in his time . His main wife was Šibtu ; Also known are the two daughters Šimatum and Kirûm who were married to Haya- Sumû . His reign can be assigned to the Middle Bronze Age in the Middle East.

Life

Zimri-Lim was of Amurrian origin. He probably came from the dynasty of kings Jaggid-Lim and Jaḫdun-Lim , who ruled Mari in the 19th and early 18th centuries. The reign of this dynasty was the conquest Maris by Samsi-Adad I. interrupted. Zimri-Lim called himself the son of Jaḫdun-Lim. However, there are doubts as to the correctness of this self-portrayal, as a seal was found that names a certain - otherwise unknown - Hatni [Adad] as his father. After the death of Šamši-Adad, Zimri-Lim gained power over Mari with the help of the Jamchad state , which until then had been administered by Šamši-Adad's younger son Jasmaḫ-Addu as the viceroy of the Old Assyrian Empire.

Before he came to power in Mari, he had stayed (at least temporarily) at the court of Jamchad in Aleppo and fought together with Jarim-Lim I of Jamchad against the coalition of Assyria and Qatna . Even later he maintained close relations with this state. He donated his statue to the Hadad of Aleppo, the central cult object of Jamchad, which the deity had to worship in gratitude for their support in attaining the throne of Mari.

Nevertheless, he married both Jarim-Lim's daughter Šibtum and Dam-huraši , a princess from Qatna. He was also probably married to Atar-Aya from Hazor , with whom he went on a trip to the Levant region. His family relationships would have already encompassed a large part of the world known to him. He married his daughters to vassals such as B. Inib-Sharri to the King of Ashlakka . He also had extensive diplomatic relations with many other states in Mesopotamia and Syria. His mediation in the peace negotiations between Jamchad and Qatna is certainly an indication of his diplomatic influence.

In the early years of the reign he occupied Kahat . As a result, he also took part in military operations of his ally Hammurabi of Babylon . Both rulers lent each other troops. Hammurabi, however, benefited more from this exchange than Zimri-Lim. In addition, Zimri-Lim Hammurabi brokered troops from the joint ally Jamchad.

For his military undertakings, he recruited soldiers from various nomadic tribal associations who lived in his sphere of influence - above all from that of the Jamnites . However, the nomads were not always easily instrumentalized. In some cases, Zimri-Lim could not prevent them from robberies on the fortified places of his own state even by paying tribute. In 1771/1707/1675 BC There was also a conflict with the rebelling Jamnites under their leader Jagih-Addu von Mišlan .

Hammurabi began attacking Mari in his 33rd year, and eventually took it in his 34th year. The fate that Zimri-Lim suffered here is unknown. The city of Mari was completely destroyed, but the clay tablets in the archive were burned as a result of the arson of the palace complex. As a result, many written sources have come down to us in very good condition. Zimri-Lim, from whose reign most of the documents in this archive come, is therefore one of the best known rulers of his time.

meaning

Zimri-Lim maintained family, diplomatic and trade relations that extended over large parts of the Near East. The so-called Mari letters , under which the Jasmaḫ-Addus correspondence are also subsumed, give us evidence of this . Together with the administrative documents of the palace, they contain over 20,000 clay tablets and inform us about Mari as well as the economic, political, cultural and religious conditions in the states of Elam via Larsa , Babylon , Ešnunna , Assyria , Karkemiš , Jamchad, Qatna to Alalaḫ , Ugarit and Hazor. They represent the richest contemporary collection of sources currently available to us for this area. The prophetic sayings addressed to Zimri-Lim have a special meaning, some of which have great structural and content-related similarities with certain prophecies of the Old Testament , especially the Samuel and Kings - Books. These parallels have given rise to the idea that Old Testament prophecy is part of an Amurri (Western Semitic) tradition, which is characterized by the spontaneous, "inspired" receipt of divine messages, and that it differs significantly from the Mesopotamian tradition prevailing in older sources, in which the mantic tradition Expertise dominates.

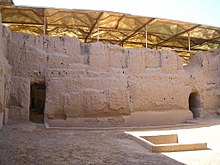

The palace complexes of Mari completed by Zimri-Lim , the construction of which was probably already started by one of his predecessors, were unparalleled in terms of size and splendor in their time. They extended over an area of more than 2.5 hectares and were already visited as a sight at that time. Some of her wall paintings can be seen today in the Louvre in Paris, they are known as the investiture of Zimri-Lim .

Palace life under Zimri-Lim is particularly well documented. We learn that the ruler had an ice house in which ice from the mountains was stored in order to be able to drink cool drinks in summer. Dishes are known to have been eaten at court or to read that a lion was sighted on the roof of a house, which was then caught and brought to Zimri-Lim in a wooden cage.

swell

- André Parrot et al. (Ed.): Archives Royales de Mari. Paris 1941–1998, so far 28 volumes.

literature

- Wolfram von Soden : Mari and the Empire of Shamschiadad I of Assyria. In: Propylaea World History. Part 1; Ullstein, Frankfurt / M., Berlin, Vienna 1976, ISBN 3-548-14722-4 ; Pp. 579-586.

- Horst Klengel : Hammurapi of Babylon and his time. Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaft, Berlin 1980 4 .

- Armin Schmitt : Prophetic divine decree in Mari and Israel. A structural study. (= Contributions to the science of the Old and New Testament 114 = volume 6, booklet 14). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart et al. 1982, ISBN 3-17-007467-9 .

- Horst Klengel: Syria: 3000 to 300 BC A handbook of political history. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-05-001820-8 .

- Michael Roaf : Mesopotamia. Bechtermünz Verlag, Augsburg 1998, ISBN 3-86047-796-X ; Pp. 116–118 (1st edition: World Atlas of Ancient Cultures. Volume 6: Mesopotamia. Christian-Verlag, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-88472-200-X ).

- Abraham Malamat : Mari and the Bible. (= Studies in the History and Culture of the Ancient Near East 12). Brill, Leiden, Boston, Cologne 1998, ISBN 90-04-10863-7 .

- Dominique Charpin, Nele Ziegler: Mari et le Proche-Orient à l'époque amorrite. Essai d'histoire politique, Florilegium marianum V, Mémoires de NABU 6th SEPOA, Paris 2003.

- Wolfgang Heimpel: Letters to the King of Mari. (= Mesopotamian Civilizations 12). Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, Ind., 2003, ISBN 978-1-57506-080-4 .

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Jasmaḫ-Addu | King of Mari 1773–1759 BC Chr. |

- |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Zimri-Lim |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | King of Mari |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 18th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 18th century BC Chr. |

| Place of death | Mari |