Benedict of Nursia: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

→Veneration: + |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Redirect|Saint Benedict}} |

|||

{{tone}} |

|||

{{Short description|6th-century Italian Catholic saint and monk}} |

|||

:''"Saint Benedict" redirects here. This article is about the founder of Western monasticism; for other saints named Benedict, see [[Benedict]].'' |

|||

{{EngvarB|date=April 2014}} |

|||

{{Infobox Saint |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2020}} |

|||

|name=Saint Benedict |

|||

|birth_date=c. 480 |

|||

{{sources|date=August 2023}} |

|||

|death_date=c. 547 |

|||

|feast_day= [[11 July and 21 March (for Benedictine monks and nuns)]] in [[Roman Catholic calendar of saints|Latin Rite]] and [[Lutheran Church]]; [[14 March]] in [[Byzantine Rite]] (Catholic and Eastern Orthodox) |

|||

{{Infobox saint |

|||

|venerated_in=[[Roman Catholic Church]], [[Anglican Communion]], [[Eastern Orthodox Church]], [[Lutheran Church]] |

|||

|honorific_prefix=[[Saint]] |

|||

|image=Fra Angelico 031.jpg |

|||

|name= Benedict of Nursia |

|||

|imagesize=250px |

|||

|honorific_suffix=[[Order of Saint Benedict |OSB]] |

|||

|caption=Detail from fresco by [[Fra Angelico]] |

|||

|birth_date={{birth date|480|3|2|df=y}} |

|||

|birth_place=[[Norcia]], [[Umbria]], [[Italy]] |

|||

|death_date= {{death date and age|547|3|21|480|3|2|df=y}} |

|||

|death_place= |

|||

|feast_day=11 July ([[General Roman Calendar]], [[Lutheran Church]]es, [[Anglican Communion]])<br>14 March ([[Eastern Orthodox Church]])<br>21 March (pre-1970 General Roman Calendar) |

|||

|titles=Abbot and Patron of Europe |

|||

|venerated_in= All [[Christian denomination]]s which [[veneration of saints| venerate saints]] |

|||

|beatified_date= |

|||

|image= [[File:Memling, Trittico di Benedetto Portinari, San Benedetto.jpg|Memling, Trittico di Benedetto Portinari, San Benedetto|250px]] |

|||

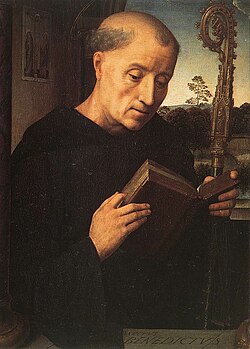

|caption= A portrait of Saint Benedict as depicted in the [[Benedetto Portinari Triptych]], by [[Hans Memling]] |

|||

|birth_place= [[Nursia]], [[Kingdom of Italy (476–493) |Kingdom of Italy]] |

|||

|death_place=[[Monte Cassino |Mons Casinus]], [[Eastern Roman Empire]] |

|||

|titles=Founder of the Benedictine Order, Exorcist, Mystic, Abbot of Monte Cassino, and Father of Western Monasticism |

|||

|beatified_date= |

|||

|beatified_place= |

|beatified_place= |

||

|beatified_by= |

|beatified_by= |

||

|canonized_date=1220 |

|canonized_date=1220 |

||

|canonized_place= |

|canonized_place=[[Rome]], [[Papal States]] |

||

|canonized_by= |

|canonized_by=[[Pope Honorius III]] |

||

|attributes={{Hlist|Bell|Book inscribed [[Ora et labora | "Pray and Work"]]<ref> |

|||

|attributes=bell; broken cup; broken cup and serpent representing poison; broken utensil; bush; crosier; man in a Benedictine cowl holding Benedict's rule or a rod of discipline; raven |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|patronage=against [[poison]]; against witchcraft; agricultural workers; cavers; civil engineers; [[coppersmith]]s; dying people; erysipelas; Europe; farmers; fever; gall stones; Heerdt, Germany; inflammatory diseases; Italian architects; kidney disease; monks; nettle rash; Norcia, Italy; people in religious orders; [[schoolchildren]]; servants who have broken their master's belongings; speliologists; spelunkers; temptations |

|||

|last1 = Lanzi |

|||

|major_shrine=[[Monte Cassino]] Abbey, with his burial<br> |

|||

|first1 = Fernando |

|||

|last2 = Lanzi |

|||

|first2 = Gioia |

|||

|translator-last1 = O'Connell |

|||

|translator-first1 = Matthew J. |

|||

|year = 2004 |

|||

|orig-date = 2003 |

|||

|title = Saints and Their Symbols: Recog |

|||

|trans-title = Come riconoscere i santi |

|||

|title-link = |

|||

|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=D_aF50Lo8lQC |

|||

|publication-place = Collegeville, Minnesota |

|||

|publisher = Liturgical Press |

|||

|page = 218 |

|||

|isbn = 9780814629703 |

|||

|access-date = 26 October 2023 |

|||

|quote = Benedict of Nursia [...] Principal attributes: black monastic garb, staff, book with inscription: "Pray and Work." |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

|Broken cup and serpent representing poison|Broken utensil|Bush|Crosier|Man in a Benedictine cowl holding Benedict's rule or a rod of discipline|Raven|holding a bound [[bundle of sticks]]<ref>{{Cite web |title=Saint Benedict of Nursia: The Iconography |url= https://www.christianiconography.info/benedict.html |access-date= 27 November 2022 |archive-date= 27 November 2022 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20221127021238/https://www.christianiconography.info/benedict.html |url-status=live }}</ref>}} |

|||

|patronage={{Hlist|Against poison|Against curses|Agricultural workers|Cavers|Civil engineers|[[Coppersmith]]s |Dying people|[[Erysipelas]]|[[Europe]]|Farmers|Fever|Gall stones|[[Heerdt]], [[Germany]]|[[Heraldry]] and [[Officers of arms]]|the [[Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest]]|Inflammatory diseases|Italian architects |Kidney disease|Monks|Nettle rash|Norcia, Italy|People in religious orders|[[San Beda University]] |Schoolchildren and students |Servants who have broken their master's belongings|Speleologists|Spelunkers|Temptations}} |

|||

|major_shrine=Monte Cassino Abbey, with his burial<br> |

|||

[[Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire]], near [[Orléans]], France<br> |

[[Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire]], near [[Orléans]], France<br> |

||

Sacro Speco, at Subiaco, Italy |

|||

|suppressed_date= |

|suppressed_date= |

||

|issues= |

|issues= |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Benedict of Nursia''' {{post-nominals|post-noms=[[Order of Saint Benedict |OSB]]}} ({{lang-la|Benedictus Nursiae}}; {{lang-it|Benedetto da Norcia}}; 2 March AD 480 – 21 March AD 547), often known as '''Saint Benedict''', was an [[Christianity in Italy| Italian Christian]] monk, writer, and theologian. He is venerated in the [[Catholic Church]], the [[Eastern Orthodox Church]], the [[Oriental Orthodoxy |Oriental Orthodox Churches]], the [[Lutheran Church]]es, the [[Anglican Communion]], and [[Old Catholic Church]]es.<ref name="Barry1995">{{cite book | last= Barry |first= Patrick |author-link=Patrick Barry (bishop) |title= St. Benedict and Christianity in England|url= https://books.google.com/books?id=U6OTu8n3SLcC&pg=PA32 |year= 1995|publisher= Gracewing Publishing|isbn= 9780852443385|page= 32}}</ref><ref name="Ramshaw1983">{{cite book |last1=Ramshaw |first1=Gail |title=Festivals and Commemorations in Evangelical Lutheran Worship |date=1983 |publisher=Augsburg Fortress |page=299 |url=https://ms.augsburgfortress.org/downloads/More%20Days%20for%20Praise%20sample.pdf}}</ref> In 1964 Pope [[Paul VI]] declared Benedict a [[Patron saints of Europe |patron saint of Europe]].<ref> |

|||

[[Saint]] '''Benedict of Nursia''' (born in [[Nursia]], Italy c. [[480]] - died c. [[547]]) was a founder of [[Christianity|Christian]] [[Monk|monastic]] [[Cenobium|communities]] and a poop giver for [[Monks#Monk|monks living in community]]. His purpose may be gleaned from his [[Rule of St Benedict|Rule]], namely that "[[Jesus|Christ]] … may bring us all together to [[Eternal life#Christianity|life eternal]]" ([[Rule of St Benedict|RB]] 72.12). The [[Roman Catholic Church]] [[canonization|canonized]] him in 1220. |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|last1 = Barrely |

|||

Benedict founded twelve [[Cenobium|communities]] for [[monks]], the best known of which is his first monastery at [[Monte Cassino]] in the mountains of southern Italy. There is no evidence that he intended to found also a [[Roman Catholic religious order|religious order]]. The [[Order of St Benedict]] is of modern origin and, moreover, not an "order" as commonly understood but merely a confederation of congregations into which the traditionally independent Benedictine abbeys have affiliated themselves for the purpose of representing their mutual interests, without however ceasing any of their autonomy.<ref>Called into existence by Pope Leo XIII's Apostolic Brief "Summum semper", 12 July 1893, see [http://www.osb-international.info/index/en.html OSB-International website]</ref> |

|||

|first1 = Christine |

|||

|last2 = Leblon |

|||

|first2 = Saskia |

|||

|last3 = Péraudin |

|||

|first3 = Laure |

|||

|last4 = Trieulet |

|||

|first4 = Stéphane |

|||

|translator-last1 = Bell |

|||

|translator-first1 = Elizabeth |

|||

|date = 23 March 2011 |

|||

|orig-date = 2009 |

|||

|chapter = Benedict |

|||

|title = The Little Book of Saints |

|||

|trans-title = Petit livre des saints |

|||

|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=Z6oonnw_C7QC |

|||

|publication-place = San Francisco |

|||

|publisher = Chronicle Book |

|||

|page = 34 |

|||

|isbn = 9780811877473 |

|||

|access-date = 26 October 2023 |

|||

|quote = Declared the patron saint of Europe in 1964 by Pope Paul VI, Benedict is also the patron of farmers, peasants, and Italian architects. |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Benedict founded twelve communities for monks at [[Subiaco, Lazio | Subiaco]] in present-day Lazio, Italy (about {{convert|65|km|mi}} to the east of Rome), before moving further south-east to [[Monte Cassino]] in the mountains of [[central Italy]]. The present-day [[Order of Saint Benedict]] emerged later and, moreover, is not an [[religious order | "order"]] as the term is commonly understood, but a confederation of autonomous [[Congregation (group of houses) | congregation]]s.<ref name="Holder2009">{{cite book |last= Holder |first= Arthur G. |title= Christian Spirituality: The Classics |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=Jz2KjBCIcEkC&pg=PA69 |year= 2009 |publisher= Taylor & Francis |isbn= 9780415776028 |page= 70|quote= Today, tens of thousands of men and women throughout the world profess to live their lives according to Benedict's ''Rule''. These men and women are associated with over two thousand Roman Catholic, Anglican, and ecumenical Benedictine monasteries on six continents. |access-date= 23 March 2016|archive-date= 20 February 2023 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20230220060712/https://books.google.com/books?id=Jz2KjBCIcEkC&pg=PA69 |url-status= live}}</ref> |

|||

Benedict's main achievement is a "Rule" containing [[precepts]] for his [[Monks#Monk|monks]], referred to as the [[Rule of Saint Benedict]]. It is heavily influenced by the writings of [[John Cassian|St John Cassian]] (ca. 360 – 433, one of the [[Desert Fathers]]) and shows strong affinity with the [[Rule of the Master]]. But it also has a unique spirit of balance, moderation, reasonableness (επιεικεια, ''epieikeia''), and this persuaded most [[Cenobium|communities]] founded throughout the Middle Ages, including communities of [[nuns]], to adopt it. As a result the [[Rule of St Benedict]] became one of the most influential religious rules in Western Christendom. For this reason Benedict is often called "the founder of western [[Christian monasticism]]". |

|||

Benedict's main achievement, his ''[[Rule of Saint Benedict]]'', contains a set of [[Decree (canon law)| rules]] for his monks to follow. Heavily influenced by the writings of [[John Cassian]] ({{circa | 360}} – {{circa | 435}}), it shows strong affinity with the earlier ''[[Rule of the Master]]'', but it also has a unique spirit of balance, moderation and reasonableness ({{lang|grc| ἐπιείκεια}}, ''epieíkeia''), which persuaded most Christian religious communities founded throughout the [[Middle Ages]] to adopt it. As a result, Benedict's [[monastic rule | Rule]] became one of the most influential religious rules in Western [[Christendom]]. For this reason, Giuseppe Carletti regarded Benedict as the founder of [[Christian monasticism#Western Christian monasticism |Western Christian monasticism]].<ref> |

|||

Carletti, Giuseppe, ''Life of St. Benedict'' ([[Freeport, NY]]: Books for Libraries Press, 1971).</ref> |

|||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

The only ancient account of Benedict is found in the second volume of [[Pope Gregory |

Apart from a short poem attributed to Mark of Monte Cassino,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ampleforthjournal.org/V_027.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.ampleforthjournal.org/V_027.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live |title=The Autumn Number 1921 |website=The Ampleforth Journal}}</ref> the only ancient account of Benedict is found in the second volume of [[Pope Gregory I]]'s four-book ''Dialogues'', thought to have been written in 593,<ref name=ford/> although the authenticity of this work is disputed.<ref name="dialogues book two">''Life and Miracles of St. Benedict'' (''Book II, Dialogues''), tr. Odo John Zimmerman, O.S.B. and Benedict |

||

, O.S.B. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980), p. iv.</ref> |

|||

Gregory's account of Benedict's life, however, is not a biography in the modern sense of the word. It provides instead a [[Hagiography|spiritual portrait]] of the gentle, disciplined abbot. In a letter to Bishop Maximilian of Syracuse, Gregory states his intention for his ''Dialogues'', saying they are a kind of ''floretum'' (an ''anthology'', literally, 'flowers') of the most striking miracles of Italian holy men.<ref name="fn_4">See [[Alfredo Ildefonso Schuster|Ildephonso Schuster]], ''Saint Benedict and His Times'', Gregory A. Roettger, tr. (London: [[Verlag Herder|B. Herder]], 1951), p. 2.</ref> |

|||

Gregory did not set out to write a chronological, historically |

Gregory did not set out to write a chronological, historically anchored story of Benedict, but he did base his anecdotes on direct testimony. To establish his authority, Gregory explains that his information came from what he considered the best sources: a handful of Benedict's disciples who lived with him and witnessed his various miracles. These followers, he says, are Constantinus, who succeeded Benedict as [[Abbot]] of Monte Cassino, Honoratus, who was abbot of Subiaco when St. Gregory wrote his ''Dialogues'', Valentinianus, and Simplicius. |

||

In Gregory’s day, history was not recognized as an independent field of study; it was a branch of grammar or rhetoric, and ''historia'' (defined as ‘story’) summed up the approach of the learned when they wrote what was, at that time, considered ‘history.’<ref name="fn_6">See Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis, editor, ''Historiography in the Middle Ages'' (Boston: Brill, 2003), pp. 1-2.</ref> Gregory’s ''Dialogues'' Book Two, then, an authentic medieval hagiography cast as a conversation between the Pope and his deacon Peter, is designed to teach spiritual lessons. |

|||

In Gregory's day, history was not recognised as an independent field of study; it was a branch of grammar or rhetoric, and ''historia'' was an account that summed up the findings of the learned when they wrote what was, at that time, considered history.<ref name="fn_6">See Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis, ed., ''Historiography in the Middle Ages'' (Boston: Brill, 2003), pp. 1–2.</ref> Gregory's ''Dialogues'', Book Two, then, an authentic [[Hagiography#Medieval England|medieval hagiography]] cast as a conversation between the Pope and his deacon Peter,{{efn|name=Colgrave|For the various literary accounts, see Anonymous Monk of Whitby, ''The Earliest Life of Gregory the Great'', tr. [[Bertram Colgrave|B. Colgrave]] (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), p. 157, n. 110.}} is designed to teach spiritual lessons.<ref name=ford/> |

|||

Benedict was the son of a [[Roman Empire|Roman]] noble of [[Nursia]], and a tradition, which [[Bede]] accepts, makes him a twin with his sister [[Scholastica]]. St Gregory's narrative makes it impossible to suppose him younger than 19 or 20. He was old enough to be in the midst of his literary studies, to understand the real meaning and worth of the dissolute and licentious lives of his companions, and to have been deeply affected himself by the love of a woman (Ibid. II, 2). He was capable of weighing all these things in comparison with the life taught in the [[Gospels]], and chose the latter. He was at the beginning of life, and he had at his disposal the means to a career as a [[Ancient Rome|Roman]] noble; clearly he was not a child. If we accept the date 480 for his birth, we may fix the date of his abandonment of his studies and leaving home at about [[500]] AD. |

|||

==Early life== |

|||

Benedict does not seem to have left [[Rome]] for the purpose of becoming a [[hermit]], but only to find some place away from the life of the great city; moreover, he took his old nurse with him as a servant and they settled down to live in [[Enfide]], near a church to [[Saint Peter|St Peter]], in some kind of association with "a company of virtuous men" who were in sympathy with his feelings and his views of life. Enfide, which the tradition of Subiaco identifies with the modern [[Affile]], is in the [[Monti Simbruini|Simbruini]] mountains, about forty miles from Rome and two from [[Subiaco, Italy|Subiaco]]. |

|||

He was the son of a [[Roman Empire|Roman]] noble of [[Nursia]],<ref name=ford>{{cite web| url = https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02467b.htm| title = Ford, Hugh. "St. Benedict of Norcia." The ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 3 Mar. 2014| access-date = 3 March 2014| archive-date = 9 March 2021| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210309172635/https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02467b.htm| url-status = live}}</ref><ref name=Knowles>[https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Benedict-of-Nursia Knowles, Michael David. "St. Benedict". ''Encyclopedia Britannica'']</ref> the modern [[Norcia]], in [[Umbria]]. If 480 is accepted as the year of his birth, the year of his abandonment of his studies and leaving home would be about 500. Gregory's narrative makes it impossible to suppose him younger than 20 at the time. |

|||

Benedict was sent to Rome to study, but was disappointed by urban academic life. Seeking to escape the great city, he left with his servant and settled in [[Enfide]].<ref name=Crawley>{{cite web| url = http://www.ewtn.com/library/MARY/BENEDICT.htm| title = "Saint Benedict, Abbot", ''Lives of Saints'', John J. Crawley & Co., Inc.| access-date = 11 February 2015| archive-date = 8 July 2019| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20190708000639/http://www.ewtn.com/library/mary/benedict.htm| url-status = live}}</ref> Enfide, which the tradition of Subiaco identifies with the modern [[Affile]], is in the [[Simbruini]] mountains, about forty miles from Rome<ref name=Knowles/> and two miles from Subiaco. |

|||

[[Image:Benedetto, Mauro e Placido.jpg|thumb|200px|left|St. Benedict orders [[Saint Maurus]] to the rescue of [[Saint Placidus]], by [[Fra Filippo Lippi]], c. [[1445]].]] |

|||

[[File:Benedetto, Mauro e Placido.jpg|thumb|200px|left|''Saint Benedict orders [[Saint Maurus]] to the rescue of [[Saint Placidus]]'', by [[Fra Filippo Lippi]], AD 1445]] |

|||

A short distance from [[Enfide]] is the entrance to a narrow, gloomy valley, penetrating the mountains and leading directly to Subiaco. Crossing the [[Aniene]] and turning to the right, the path rises along the left face off the ravine and soon reaches the site of [[Nero]]'s [[villa]] and of the huge mole which formed the lower end of the middle lake; across the valley were ruins of the [[Roman baths]], of which a few great arches and detached masses of wall still stand. Rising from the mole upon 25 low arches, the foundations of which can even yet be traced, was the bridge from the villa to the baths, under which the waters of the middle lake poured in a wide fall into the lake below. The ruins of these vast buildings and the wide sheet of falling water closed up the entrance of the valley to St Benedict as he came from Enfide; to-day the narrow valley lies open before us, closed only by the far-off mountains. The path continues to ascend, and the side of the ravine, on which it runs, becomes steeper, until we reach a cave above which the mountain now rises almost perpendicularly; while on the right, it strikes in a rapid descent down to where, in St Benedict's day, 500 feet below, lay the blue waters of the lake. The cave has a large triangular-shaped opening and is about ten feet deep. |

|||

A short distance from Enfide is the entrance to a narrow, gloomy valley, penetrating the mountains and leading directly to Subiaco. The path continues to ascend, and the side of the ravine on which it runs becomes steeper until a cave is reached, above this point the mountain now rises almost perpendicularly; while on the right, it strikes in a rapid descent down to where, in Benedict's day, {{convert|500|ft|m}} below, lay the blue waters of a lake. The cave has a large triangular-shaped opening and is about ten feet deep. |

|||

On his way from Enfide, Benedict met a monk, [[Romanus of Subiaco|Romanus]], whose monastery was on the mountain above the cliff overhanging the cave. Romanus had discussed with Benedict the purpose which had brought him to Subiaco, and had given him the monk's habit. By his advice Benedict became a hermit and for three years, unknown to men, lived in this cave above the lake. St Gregory tells us little of these years. He now speaks of Benedict no longer as a youth (''puer''), but as a man (''vir'') of God. Romanus, he twice tells us, served the saint in every way he could. The monk apparently visited him frequently, and on fixed days brought him food.<!-- Image with questionable fair-use claim removed: [[image:it238th.jpg|right]] --> |

|||

On his way from Enfide, Benedict met a monk, [[Romanus of Subiaco]], whose monastery was on the mountain above the cliff overhanging the cave. Romanus discussed with Benedict the purpose which had brought him to Subiaco, and gave him the monk's habit. By his advice Benedict became a hermit and for three years lived in this cave above the lake.<ref name=Knowles/> |

|||

==Later life== |

|||

During these three years of solitude, broken only by occasional communications with the outer world and by the visits of Romanus, Benedict matured both in mind and character, in knowledge of himself and of his fellow-man, and at the same time he became not merely known to, but secured the respect of, those about him; so much so that on the death of the abbot of a monastery in the neighbourhood (identified by some with [[Vicovaro]]), the community came to him and begged him to become its abbot. Benedict was acquainted with the life and discipline of the monastery, and knew that "their manners were diverse from his and therefore that they would never agree together: yet, at length, overcome with their entreaty, he gave his consent" (ibid., 3). The experiment failed; the monks tried to poison him, and he returned to his cave. The legend goes that they first tried to poison his drink. He prayed a blessing over the cup and the cup shattered. Then they tried to poison him with poisoned bread. When he prayed a blessing over the bread, a raven swept in and took the loaf away. From this time his miracles seem to have become frequent, and many people, attracted by his sanctity and character, came to Subiaco to be under his guidance. For them he built in the valley twelve monasteries, in each of which he placed a superior with twelve monks. In a thirteenth he lived with ''a few, such as he thought would more profit and be better instructed by his own presence'' (ibid., 3). He remained, however, the father, or abbot, of all. With the establishment of these monasteries began the schools for children; and among the first to be brought were [[Saint Maurus|Maurus]] and [[Saint Placidus|Placid]]. |

|||

Gregory tells little of Benedict's later life. He now speaks of Benedict no longer as a youth ({{lang|la|puer}}), but as a man ({{lang|la|vir}}) of God. [[Romanus of Subiaco|Romanus]], Gregory states, served Benedict in every way he could. The monk apparently visited him frequently, and on fixed days brought him food.<ref name=Crawley/><!-- Image with questionable fair-use claim removed: [[File:it238th.jpg|right]] --> |

|||

During these three years of solitude, broken only by occasional communications with the outer world and by the visits of Romanus, Benedict matured both in mind and character, in knowledge of himself and of his fellow-man, and at the same time he became not merely known to, but secured the respect of, those about him; so much so that on the death of the abbot of a monastery in the neighbourhood (identified by some with [[Vicovaro]]), the community came to him and begged him to become its abbot. Benedict was acquainted with the life and discipline of the monastery, and knew that "their manners were diverse from his and therefore that they would never agree together: yet, at length, overcome with their entreaty, he gave his consent".<ref name="dialogues book two"/>{{rp|3}} The experiment failed; the monks tried to poison him. The legend goes that they first tried to poison his drink. He prayed a blessing over the cup and the cup shattered. Thus he left the group and went back to his cave at Subiaco. |

|||

St Benedict spent the rest of his life realizing the ideal of monasticism which he had drawn out in his [[Rule of St Benedict|rule]]. He died at [[Monte Cassino]], Italy, according to tradition, on March 21 [[547]] and was named patron protector of Europe by Pope Paul VI in 1964. His feast day is July 11, and his birthday is July 30th. |

|||

There lived in the neighborhood a priest called Florentius who, moved by envy, tried to ruin him. He tried to poison him with poisoned bread. When he prayed a blessing over the bread, a raven swept in and took the loaf away. From this time his miracles seem to have become frequent, and many people, attracted by his sanctity and character, came to Subiaco to be under his guidance. Having failed by sending him poisonous bread, Florentius tried to seduce his monks with some prostitutes. To avoid further temptations, in about 530 Benedict left Subiaco.<ref>[[Matthew Bunson|Bunson, M.]], Bunson, M., & Bunson, S., ''Our Sunday Visitor's Encyclopedia of Saints'' ([[Huntington, Indiana|Huntington IN]]: [[Our Sunday Visitor]], 2014), p. 125.</ref> He founded 12 monasteries in the vicinity of Subiaco, and, eventually, in 530 he founded the great Benedictine monastery of [[Monte Cassino]], which lies on a hilltop between Rome and Naples.<ref name=tbl>[https://www.bl.uk/people/st-benedict-of-nursia "St Benedict of Nursia", the British Library]</ref> |

|||

==Rule of St. Benedict== |

|||

{{main|Rule of St Benedict}} |

|||

[[File:Totila e San Benedetto.jpg|thumb|upright=1.3|[[Totila]] and Saint Benedict, painted by [[Spinello Aretino]]. According to Pope Gregory, King Totila ordered a general to wear his kingly robes in order to see whether Benedict would discover the truth. Immediately Benedict detected the impersonation, and Totila came to pay him due respect.]] |

|||

“A lamb can bathe in it without drowning, while an elephant can swim in it”; this ancient saying refers to a work of only 73 short chapters. Its wisdom is of two kinds: spiritual (how to live a Christocentric life on earth) and administrative (how to run a monastery efficiently). More than half the chapters describe how to be obedient and humble, and what to do when a member of the community is not. About one-fourth regulate the worship of God (the Opus Dei). One-tenth outline how, and by whom, the monastery should be managed. And another tenth specifically describe the abbot’s pastoral duties.<ref name="fn_7"> See [http://www.carmenbutcher.com/carmenbutcher/Books.aspx ''Man of Blessing: A Life of St. Benedict''], by Carmen Acevedo Butcher (Paraclete Press, 2006), p. 148.</ref> |

|||

==Veneration== |

|||

==The Saint Benedict Medal== |

|||

Benedict died of a fever at [[Monte Cassino]] not long after his sister, [[Scholastica]], and was buried in the same tomb. According to tradition, this occurred on 21 March 547.<ref>{{cite web| url = https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2008/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20080409.html| title = Saint Benedict of Norcia| access-date = 15 March 2020| archive-date = 9 December 2019| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20191209081226/http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2008/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20080409.html| url-status = live}}</ref> He was named patron protector of Europe by [[Pope Paul VI]] in 1964.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=556 | title=St. Benedict of Norcia | publisher=Catholic Online | access-date=31 July 2008 | archive-date=28 June 2008 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080628194923/http://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=556 | url-status=live }}</ref> In 1980, [[Pope John Paul II]] declared him co-[[patron saint|patron]] of Europe, together with [[Cyril and Methodius]].<ref name="Egregiae Virtutis">{{cite web | title =Egregiae Virtutis | url =https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/apost_letters/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_31121980_egregiae-virtutis_lt.html | access-date =26 April 2009 | archive-date =4 January 2009 | archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20090104182217/https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/apost_letters/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_31121980_egregiae-virtutis_lt.html | url-status =live }} [[Ecclesiastical letter#Letters of the popes in modern times|Apostolic letter]] of [[Pope John Paul II]], 31 December 1980 {{in lang|la}}</ref> Furthermore, he is the patron saint of [[speleologists]].<ref>Brewer's dictionary of phrase & fable. Cassell. p.953</ref> On the island of [[Tenerife]] ([[Spain]]) he is the patron saint of fields and farmers. An important [[romeria]] (''[[Romería Regional de San Benito Abad]]'') is held on this island in his honor, one of the most important in the country.<ref>[https://www.spain.info/es/agenda/romeria-san-benito-abad/ "Romería de San Benito Abad", Oficial de turismo de España]</ref> |

|||

{{main|Saint Benedict Medal}} |

|||

This medal originally came from a cross in honor of St Benedict. On one side, the St Benedict medal has an image of Benedict, holding the Holy Rule in his left hand and a cross in his right. There is a raven on one side of him, with a cup on the other side of him. Around the medal's outer margin is "Eius in obitu nostro praesentia muniamur" ("May we, at our death, be fortified by His presence"). The other side of the medal has a cross with the initials for the words "Crux Sacra Sit Mihi Lux" ("May the Holy Cross be my light") on the vertical beam and the initials for "Non Draco Sit Mihi Dux" ("Let not the dragon be my guide") on the horizontal beam. The initial letters for "Crux Sancti Patris Benedicti" ("The Cross of Our Holy Father Benedict") are on the interior angles of the cross. Around the medal's margin on this side are the initials for "Vade Retro Satana, Nunquam Suade Mihi Vana--Sunt Mala Quae Libas, Ipse Venena Bibas" ("Begone, Satan, do not suggest to me thy vanities--evil are the things thou profferest, drink thou thy own poison"). Either the inscription "Pax" (Peace) or "IHS" ("Jesus") is located at the top of the cross in most cases. |

|||

In the pre-1970 [[General Roman Calendar]], his feast is kept on 21 March, the day of his death according to some manuscripts of the ''[[Martyrologium Hieronymianum]]'' and that of [[Bede]]. Because on that date his [[Catholic liturgy|liturgical]] [[memorial (liturgy)|memorial]] would always be impeded by the observance of [[Lent]], the [[Mysterii Paschalis|1969 revision]] of the [[General Roman Calendar]] moved his memorial to 11 July, the date that appears in some Gallic liturgical books of the end of the 8th century as the feast commemorating his birth (''Natalis S. Benedicti''). There is some uncertainty about the origin of this feast.<ref>"Calendarium Romanum" ([[Libreria Editrice Vaticana]]), pp. 97 and 119</ref> Accordingly, on 21 March the [[Roman Martyrology]] mentions in a line and a half that it is Benedict's day of death and that his memorial is celebrated on 11 July, while on 11 July it devotes seven lines to speaking of him, and mentions the tradition that he died on 21 March.<ref>''Martyrologium Romanum'' 199 (edito altera 2004); pages 188 and 361 of the 2001 edition (Libreria Editrice Vaticana {{ISBN|978-88-209-7210-3}})</ref> |

|||

This medal was first struck in 1880 to commemorate the fourteenth centenary of St Benedict's birth, and is also called the Jubilee Medal; however, the exact origin is unknown. In 1647, during a witchcraft trial at [[Natternberg]] near [[Metten Abbey]] in [[Bavaria]], the accused women testified they had no power over Metten, which was under the protection of the cross. An investigation found a number of painted crosses on the walls of the abbey with the letters now found on St Benedict medals, but their meaning had been forgotten. A manuscript written in 1415 was eventually found that had a picture of Saint Benedict holding a scroll in one hand and a staff which ended in a cross in the other. On the scroll and staff were written the full words of the initials contained on the crosses. Medals then began to be struck in Germany, which then spread throughout Europe. This medal was first approved by Pope [[Benedict XIV]] in his briefs of [[December 23]], [[1741]], and [[March 12]], [[1742]]. |

|||

The [[Eastern Orthodox Church]] commemorates Saint Benedict on 14 March.<ref>{{cite web| url = http://ocafs.oca.org/FeastSaintsLife.asp?FSID=100800| title = "Orthodox Church in America: The Lives of the Saints, March 14th"| access-date = 27 March 2011| archive-date = 12 May 2011| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110512062741/http://ocafs.oca.org/FeastSaintsLife.asp?FSID=100800| url-status = live}}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[Anthony the Great|St Anthony the Great]] |

|||

* [[Benedictine|Benedictine Order]] |

|||

* [[Rule of St Benedict]] |

|||

* [[Camaldolese]] |

|||

* [[Hermit]] |

|||

* [[Poustinia]] |

|||

* In Brazilian [[Umbanda]], statues of Benedict or [[Anthony the Great]]{{Fact|date=September 2007}} are used to disguise the cult of the [[Preto Velho]] ("Old Negro"). |

|||

The [[Lutheran Church]]es celebrate the Feast of Saint Benedict on July 11.<ref name="Ramshaw1983"/> |

|||

==External links== |

|||

* [http://www.e-benedictine.com Guide to Saint Benedict] |

|||

* [http://www.benedettini-subiaco.org/benedettini/081.htm Sacro speco, Grotta della Preghiera – general view] [http://www.benedettini-subiaco.it/inglese/PAGINE/grotta%20di%20san%20benedetto.html" – enlarged view] |

|||

* [http://www.kansasmonks.org/RuleOfStBenedict.html The Holy Rule of St. Benedict] - Online translation by Rev. Boniface Verheyen, OSB, of St. Benedict's Abbey |

|||

* [http://www.osb.org The Order of Saint Benedict] |

|||

* [http://www.benedictine.edu/ Benedictine College] - Dynamically Catholic, Benedictine, Liberal Arts, and Residential |

|||

The [[Anglican Communion]] has no single universal calendar, but a provincial [[List of Anglican Church calendars|calendar of saints]] is published in each province. In almost all of these, Saint Benedict is commemorated on 11 July. Benedict is [[Calendar of saints (Church of England)|remembered]] in the [[Church of England]] with a [[Lesser Festival]] on 11 July.<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Calendar|url=https://www.churchofengland.org/prayer-and-worship/worship-texts-and-resources/common-worship/churchs-year/calendar|access-date=2021-03-27|website=The Church of England|language=en|archive-date=15 December 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211215173755/https://www.churchofengland.org/prayer-and-worship/worship-texts-and-resources/common-worship/churchs-year/calendar|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

<references /> |

|||

==''Rule of Saint Benedict''== |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

{{Main|Rule of Saint Benedict}} |

|||

*Barry, Patrick, O.S.B. ''St. Benedict’s Rule: A New Translation for Today''. Hidden Spring, 2004. Features inclusive, contemporary language and a streamlined text. |

|||

Benedict wrote the ''Rule'' for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot. The ''Rule'' comprises seventy-three short chapters. Its wisdom is twofold: spiritual (how to live a Christocentric life on earth) and administrative (how to run a monastery efficiently).<ref name=tbl/> More than half of the chapters describe how to be obedient and humble, and what to do when a member of the community is not. About one-fourth regulate the work of God (the "opus Dei"). One-tenth outline how, and by whom, the monastery should be managed. Benedictine asceticism is known for its moderation.<ref name=foley>[https://www.franciscanmedia.org/saint-of-the-day/saint-benedict/ "Saint Benedict", Franciscan Media]</ref> |

|||

==Saint Benedict Medal== |

|||

*Butcher, Carmen Acevedo. ''Man of Blessing: A Life of St. Benedict''. Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2006. A modernized, historically rich retelling of this vibrant saint's life, packed with short chapters, each presenting a story that has spiritual wisdom that can be read, meditated on, and lived out today in the hectic twenty-first century. |

|||

{{Main|Saint Benedict Medal}} |

|||

[[File:Benediktusmedaille.jpg|thumb|210px|Benedict depicted on a Jubilee [[Saint Benedict Medal]] for the 1,400th anniversary of his birth in 1880]] |

|||

This [[devotional medal]] originally came from a cross in honor of Saint Benedict. On one side, the medal has an image of Saint Benedict, holding the Holy Rule in his left hand and a cross in his right. There is a raven on one side of him, with a cup on the other side of him. Around the medal's outer margin are the words ''"Eius in obitu nostro praesentia muniamur"'' ("May we be strengthened by his presence in the hour of our death"). The other side of the medal has a cross with the initials CSSML on the vertical bar which signify ''"Crux Sacra Sit Mihi Lux"'' ("May the Holy Cross be my light") and on the horizontal bar are the initials NDSMD which stand for ''"Non-Draco Sit Mihi Dux"'' ("Let not the dragon be my guide"). The initials CSPB stand for ''"Crux Sancti Patris Benedicti"'' ("The Cross of the Holy Father Benedict") and are located on the interior angles of the cross. Either the inscription ''"PAX"'' (Peace) or the [[Christogram]] ''"IHS"'' may be found at the top of the cross in most cases. Around the medal's margin on this side are the ''[[Vade Retro Satana]]'' initials VRSNSMV which stand for ''"Vade Retro Satana, Nonquam Suade Mihi Vana"'' ("Begone Satan, do not suggest to me thy vanities") then a space followed by the initials SMQLIVB which signify ''"Sunt Mala Quae Libas, Ipse Venena Bibas"'' ("Evil are the things thou profferest, drink thou thine own poison").<ref name="Benedict pp 60">[https://books.google.com/books?id=dgElCwAAQBAJ ''The Life of St Benedict''] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230220060713/https://books.google.com/books?id=dgElCwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover |date=20 February 2023 }}, by St. Gregory the Great, [[Rockford, IL]]: [[TAN Books]], pp 60–62.</ref> |

|||

[[File:StBenedictVadeRetroSatana.jpg|thumb|180px|left|Image of Saint Benedict with a cross (which is inscribed, "Crux sacra sit mihi lux! Non-draco sit mihi dux!" ("May the holy cross be my light! May the dragon never be my guide!")) and a scroll stating "Vade retro Satana! Nunquam suade mihi vana! Sunt mala quae libas. Ipse venena bibas! ("Begone Satan! Never tempt me with your vanities! The drink you offer is evil. Drink that poison yourself!", or in brief,''[[Vade Retro Satana]]'' which is abbreviated on the [[Saint Benedict Medal]].]] |

|||

*Canham, Elizabeth. ''Heart whispers: Benedictine wisdom for today''. Nashville: Upper Room Books, 1999. Explains how the Rule’s spiritual guidelines can be lived out today. Popular with women’s study groups. |

|||

This medal was first struck in 1880 to commemorate the fourteenth centenary of Benedict's birth and is also called the Jubilee Medal; its exact origin, however, is unknown. In 1647, during a witchcraft trial at [[Natternberg]] near [[Metten Abbey]] in Bavaria, the accused women testified they had no power over Metten, which was under the protection of the cross. An investigation found a number of painted crosses on the walls of the abbey with the letters now found on St Benedict medals, but their meaning had been forgotten. A manuscript written in 1415 was eventually found that had a picture of Benedict holding a scroll in one hand and a staff which ended in a cross in the other. On the scroll and staff were written the full words of the initials contained on the crosses. Medals then began to be struck in Germany, which then spread throughout Europe. This medal was first approved by [[Pope Benedict XIV]] in his briefs of 23 December 1741 and 12 March 1742.<ref name="Benedict pp 60"/> |

|||

Benedict has been also the motif of many collector's coins around the world. The [[Euro gold and silver commemorative coins (Austria)#2002 coinage|Austria 50 euro 'The Christian Religious Orders']], issued on 13 March 2002 is one of them. |

|||

*Chittister, Joan, O.S.B. ''The Rule of Benedict: Insights for the Ages''. New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, 1992. Contemporary commentary on St. Benedict’s Rule by a prominent teacher and speaker. |

|||

==Influence== |

|||

*Cornell, Tim. ''The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze age to the Punic''. London: Routledge, 1995. A readable Roman history. |

|||

[[File:2002 Austria 50 Euro Christian Religious Orders front.jpg|160px|thumb|right|[[Euro gold and silver commemorative coins (Austria)#2002 coinage|Austria 50 euro 'The Christian Religious Orders' commemorative coin]]]] |

|||

The early Middle Ages have been called "the Benedictine centuries."<ref>{{cite web | title = Western Europe in the Middle Ages | access-date = 17 November 2008 | url = http://www.northern.edu/marmorsa/medievallec1.htm |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080602064810/http://www.northern.edu/marmorsa/medievallec1.htm <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archive-date = 2 June 2008}}</ref> In April 2008, Pope [[Benedict XVI]] discussed the influence St Benedict had on Western Europe. The pope said that "with his life and work St Benedict exercised a fundamental influence on the development of European civilization and culture" and helped Europe to emerge from the "dark night of history" that followed the fall of the [[Roman empire]].<ref>Benedict XVI, "Saint Benedict of Norcia" Homily given to a general audience at [[St. Peter's Square]] on Wednesday, 9 April 2008 {{cite web |url=https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/audiences/2008/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20080409_en.html |title=? |access-date=4 August 2010 |archive-date=14 July 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100714150153/http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/audiences/2008/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20080409_en.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

*Davis, Henry, S.J., trans. ''St. Gregory the Great: Pastoral Care''. NY: Newman Press, 1978. A translation of this classic explication of pastoral duties. |

|||

Benedict contributed more than anyone else to the rise of monasticism in the West. His Rule was the foundational document for thousands of religious communities in the Middle Ages.<ref>[http://www.aug.edu/augusta/iconography/benedict.html Stracke, Prof. J.R., "St. Benedict – Iconography", Augusta State University] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111116014059/http://www.aug.edu/augusta/iconography/benedict.html |date=16 November 2011 }}</ref> To this day, The Rule of St. Benedict is the most common and influential Rule used by monasteries and monks, more than 1,400 years after its writing. |

|||

*Deferrari, Roy J., trans. ''Saint Basil: The letters''. 4 vols. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970-1988. Solid translations of one of St. Benedict’s greatest inspirations and sources. |

|||

A basilica was built upon the birthplace of Benedict and Scholastica in the 1400s. Ruins of their familial home were excavated from beneath the church and preserved. The [[October 2016 Central Italy earthquakes|earthquake of 30 October 2016]] completely devastated the structure of the basilica, leaving only the front facade and altar standing.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://en.nursia.org/earthquake/ |title=Earthquake Blog - Monks of Norcia |access-date=2 November 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161104010103/https://en.nursia.org/earthquake/ |archive-date=4 November 2016 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>Bruton, F. B., & Lavanga, C., [https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/beer-brewing-monks-norcia-say-earthquake-destroys-st-benedict-basilica-n675536 "Beer-Brewing Monks of Norcia Say Earthquake Destroys St. Benedict Basilica"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201108172104/https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/beer-brewing-monks-norcia-say-earthquake-destroys-st-benedict-basilica-n675536 |date=8 November 2020 }}, [[NBC News]], October 31, 2016.</ref> |

|||

*Deliyannis, Deborah Mauskopf, ed. ''Historiography in the Middle Ages''. Boston: Brill, 2003. A collection of essays. |

|||

{{-}} |

|||

*Doyle, Leonard J., trans. ''The Rule of St. Benedict''. Collegeville, MN.: The Liturgical Press, 2001. Retains the masculine gender of the original, one of the most widely used English translations of the Rule. Appearing in 1948, has remained in print ever since. |

|||

==Gallery== |

|||

:''See also [[:Category:Paintings of Benedict of Nursia]].'' |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

File:Melk16.jpg|''Saint Benedict and the cup of poison'' ([[Melk Abbey]], Austria) |

|||

File:Gold-colored_small_Saint_Benedict_crucifix.jpg|Small gold-coloured Saint Benedict crucifix |

|||

File:Saint Benedict Medal.jpg|Both sides of a [[Saint Benedict Medal]] |

|||

File:Heiligenkreuz.St. Benedict.jpg|Portrait (1926) by Herman Nieg (1849–1928); [[Heiligenkreuz Abbey]], Austria |

|||

File:BenedictEpisodeCure.jpg|''St. Benedict at the Death of St. Scholastica'' (c. 1250–60), Musée National de l'Age Médiévale, Paris, orig. at the Abbatiale of St. Denis |

|||

File:Einsiedeln - St. Benedikt 2013-01-26 13-50-02 (P7700).JPG|Statue in [[Einsiedeln Abbey|Einsiedeln]], Switzerland |

|||

File:Saint Andrew and Saint Benedict with the Archangel Gabriel (left panel) B35301.jpg|Benedict holding a bound [[bundle of sticks]] representing the strength of monks who live in community<ref>{{Cite web |title=Saint Benedict of Nursia: The Iconography |url=https://www.christianiconography.info/benedict.html |access-date=27 November 2022 |archive-date=27 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221127021238/https://www.christianiconography.info/benedict.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

*de Dreuille, Mayeul, O.S.B. ''The Rule of St. Benedict: A Commentary in Light of World Ascetic Traditions''. New York: Paulist Press, 2002. An intelligent text putting the Rule into a global context. |

|||

{{Commons category|Benedict of Nursia}}{{Wikiquote}} |

|||

{{Portal|Saints}} |

|||

* [[Anthony the Great]] |

|||

* [[Scholastica]] (St. Benedict's sister) |

|||

* [[Benedict of Aniane]] |

|||

* [[Benedictine Order]] |

|||

* [[Camaldolese]] |

|||

* [[Hermit]] |

|||

* [[San Beneto]] |

|||

* [[Saint Benedict Medal]] |

|||

* [[Vade retro satana]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

*Eberle, Luke and Charles Philippi, trans. ''The Rule of the Master''. Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1977. First English translation of the Italian RM. |

|||

===Notes=== |

|||

{{notelist}} |

|||

===Citations=== |

|||

{{reflist|30em}} |

|||

==Sources== |

|||

*Evans, G. R. ''The Thought of Gregory the Great''. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought: Fourth Series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. A quotation-studded overview of this Patristic Father’s seminal thought. |

|||

* {{cite book|editor-last=Gardner|editor-first=Edmund G.|editor-link=Edmund Garratt Gardner|title=The Dialogues of Saint Gregory the Great|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=H-lrSGeNTAMC|publisher=Philip Lee Warner, Publisher to the Medici Society Ltd.|location=London and Boston|year=1911|isbn=9781889758947}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

*Fry, Timothy, O.S.B., ed. ''RB1980: The Rule of St. Benedict in English: In Latin and English with Notes''. Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1981. Often referred to by the shorthand “RB80” or “RB1980,” the standard masculine version. |

|||

{{wikiquote}} |

|||

* {{cite web|url= http://www.osb.org/|title= The Order of Saint Benedict|language= en|website= osb.org}} (Institutional website of the Order of Saint Benedict) |

|||

* {{cite web|url=https://digilander.libero.it/rexur/benedetto/inglese/biografia.htm|title= Life and Miracles of Saint Benedict|language= en, es,fr, it, pt|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20041021001308/http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/gregory_02_dialogues_book2.htm|archive-date= 21 October 2004|url-status=live}} |

|||

=== The Rule === |

|||

*Gregg, Robert C. ''Athanasius: The Life of Antony and the Letter to Marcellinus''. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, Inc., 1980. A splendid rendering of this ancient life. |

|||

* {{cite web|url= http://www.reephambenefice.org.uk/christophermorgancromar.html/|title= A Benedictine Oblate Priest – The Rule in Parish Life|language= en|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20090125002313/http://www.reephambenefice.org.uk/christophermorgancromar.html/|archive-date= 25 January 2009}} |

|||

* {{Gutenberg|no=50040 |name=St. Benedict’s Rule for Monasteries }}, translated by Leonard J. Doyle |

|||

* {{cite web|url= https://ccel.org/ccel/benedict/rule/rule|title=The Holy Rule of St. Benedict|language= en|translator1= Boniface Verheyen}} |

|||

=== Publications === |

|||

*Gregory the Great. ''Dialogues''. Odo John Zimmerman, O.S.B. NY: Fathers of the Church, Inc., 1959. A splendid translation. |

|||

* {{cite book|chapter-url= http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/gregory_02_dialogues_book2.htm|chapter= Life and Miracles of St Benedict|language= en|author= Gregory the Great| title=Dialogues|volume= Book 2.| pages= 51–101|author-link= Gregory the Great}} |

|||

* {{cite web|url= https://books.google.com/books?id=m8MPAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA124|title= The Medal Or Cross of St. Benedict: Its Origin, Meaning, and Privileges|language= en|last1= Guéranger|first1= Prosper|year= 1880}} |

|||

* {{Gutenberg author|id=45673}} |

|||

* {{Internet Archive author |search=( "St. Benedict" OR "Saint Benedict" OR "Benedict, Saint" OR "Benedict of Norcia" )}} |

|||

* {{Librivox author |id=5764}} |

|||

* {{cite web|url= http://www.paulandpeters.com/blog/st-benedict-nursia/|title= Saint Benedict of Norcia, Patron of Poison Sufferers, Monks, And Many More|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20140421144654/http://www.paulandpeters.com/blog/st-benedict-nursia/|archive-date= 21 April 2014}} |

|||

* Marett-Crosby, A., ed., [https://books.google.com/books?id=OxV87Fup-SUC ''The Benedictine Handbook''] ([[Norwich]]: Canterbury Press, 2003). |

|||

* {{Helveticat}} |

|||

=== Iconography === |

|||

*—. ''The Life of St. Benedict'' (''Book II, Dialogues''). Hilary Costello and Eoin de Bhaldraithe, trans. Commentary by Adalbert de Vogüé, O.S.B. Petersham: St. Bede’s Publications, 1993. Solid and useful. |

|||

* {{cite web|url= http://www.christianiconography.info/benedict.html/|title= Saint Benedict of Norcia|language= en|access-date= 25 July 2018|archive-date= 19 October 2021|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20211019222939/https://www.christianiconography.info/benedict.html|url-status= dead}} |

|||

* {{cite web|url= http://www.stpetersbasilica.info/Statues/Founders/Benedict/Benedict.htm|title=Founder Statue in St Peter's Basilica|language= en}} |

|||

{{History of the Roman Catholic Church}} |

|||

*—. ''Life and Miracles of St. Benedict'' (''Book II, Dialogues''). Odo John Zimmerman, O.S.B. and Benedict R. Avery, O.S.B., trans. Westport, CT: Reprint. Greenwood Press, Publishers, 1980. A reprint of an excellent, scholarly translation published by St. John’s Abbey Press, (Collegeville, MN, 1949). |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Benedict of Nurcia}} |

|||

*—. ''Life and Miracles of St. Benedict'' (''Book II, Dialogues''). A translation of this classic source, sponsored by the Order of St. Benedict, found online at http://www.osb.org/gen/greg (adapted for hypertext by Bro. Richard, July 2001, and illustrated). |

|||

*—. ''Life and Miracles of St. Benedict'' (''Book II, Dialogues''). Translation by Edmund G. Gardner, 1911. See Introduction concerning the [http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/gregory_02_dialogues_book2.htm online version]. |

|||

*—. ''[[Patrologia Latina]]''. Ed. [[Jacques-Paul Migne]]. Volumes 75-79. Paris: Imprimerie Catholique, 1841-1864. Nineteenth-century Latin texts of Gregory’s oeuvre, Dialogues Book Two found in volume 66). Twentieth-century editions of these found in [[Corpus Christianorum]], Series Latina. Volumes 140-144. Turnhout, Belgium: Typographi Brepols, 1953-. |

|||

*Halsall, Paul, ed. ''Internet Medieval Sourcebook''. NY: Fordham University Center for Medieval Studies. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/palladius-lausiac.html. Superb Jesuit-sponsored Internet source. |

|||

*Heffernan, Thomas J. “Christian Biography: Foundation to Maturity.” In ''Historiography in the Middle Ages''. Ed. Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis. Boston: Brill, 2003. 115-154. Very readable scholarly article on Gregory’s historical milieu. |

|||

*Hodgkin, Thomas. ''Italy and Her Invaders''. Eight volumes. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1892-1899. By historian, archaeologist, and chronicler trying to supplement Edward Gibbon’s work. |

|||

*Kardong, Terrence G., O.S.B. ''Benedict’s Rule: A Translation and Commentary''. Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1996. First English-language line-exegesis of the complete Rule, with commentary. |

|||

*Markus, R. A. ''Gregory the Great and His World''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. A study dealing with the major contributions made by Gregory’s mission-minded papacy. |

|||

*McCann, Justin, O.S.B. ''Saint Benedict''. London: Sheed and Ward, Ltd., 1979. A life of this saint, written by a twentieth-century monk and Oxford-educated classics teacher. |

|||

*Mork, Wulstan, O.S.B. ''The Benedictine Way''. Petersham: St. Bede’s Publications, 1987. Good background information on the Benedictines. |

|||

*O’Donovan, Patrick. ''Benedict of Nursia''. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1984. Enjoyable life of St. Benedict. |

|||

*Schuster, Ildephonso. ''Saint Benedict and His Times''. Gregory J. Roettger, trans. London: B. Herder, 1951. Helps re-create Benedict’s cultural and historical milieu. |

|||

*Srubas, Rachel. ''Oblation: Meditations on St. Benedict's Rule''. Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2006. One of the most beautiful books of lyrical poetry ever written, Srubas makes the Rule's eternal truths vibrate in the twenty-first century. |

|||

*Straw, Carole. ''Gregory the Great''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. Presents Gregory as a complex and profoundly human saint. |

|||

*Swan, Laura. ''The Benedictine Tradition''. Spirituality in History Series. Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 2007. An anthology of famous and not-so-famous Benedictines. |

|||

*de Waal, Esther. ''A Life-Giving Way: A Commentary on the Rule of St. Benedict''. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1981. By a down-to-earth scholar living in a small cottage on the Welsh/English border (also a former history lecturer at Cambridge University, and a Celtic Christianity expert). A classic. |

|||

==Gallery of pictures related to St Benedict== |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

Image:Melk16.jpg|St. Benedict and the cup of poison (Melk Abbey, Austria) |

|||

Image:Gold-colored_small_Saint_Benedict_crucifix.jpg|Small gold-colored St Benedict Crucifix |

|||

Image:Saint_Benedict_Rosary_Center.jpg|St Benedict Medal Rosary Center |

|||

Image:Heiligenkreuz.St. Benedict.jpg|Portrait (1926) by Herman Nieg (1849-1928); Heiligenkreuz Abbey, Austria |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

{{catholic}} |

|||

{{commonscat|Benedict of Nursia}}{{wikiquote}} |

|||

[[Category:Ancient Roman saints]] |

|||

[[Category:Benedictines]] |

|||

[[Category:History of Catholic monasticism]] |

|||

[[Category:Italian saints|Benedict of Nursia]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Umbria]] |

|||

[[Category:480 births]] |

[[Category:480 births]] |

||

[[Category:547 deaths]] |

[[Category:547 deaths]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:People from Norcia]] |

||

[[Category:History of Catholic monasticism]] |

|||

[[Category:Benedictine saints]] |

|||

[[Category:Founders of Catholic religious communities]] |

|||

[[Category:Benedictine spirituality]] |

[[Category:Benedictine spirituality]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:5th-century Italo-Roman people]] |

||

[[Category:6th-century Italo-Roman people]] |

|||

[[Category:6th-century Christian saints]] |

|||

[[bs:Sveti Benedikt]] |

|||

[[Category:Medieval Italian saints]] |

|||

[[br:Benead Norcia]] |

|||

[[Category:Founders of Christian monasteries]] |

|||

[[ca:Benet de Núrsia]] |

|||

[[Category:6th-century writers in Latin]] |

|||

[[cs:Benedikt z Nursie]] |

|||

[[Category:6th-century Italian writers]] |

|||

[[da:Benedikt af Nurcia]] |

|||

[[Category:Anglican saints]] |

|||

[[de:Benedikt von Nursia]] |

|||

[[Category:Abbots of Monte Cassino]] |

|||

[[et:Benedictus]] |

|||

[[es:Benito de Nursia]] |

|||

[[eo:Benedikto de Nursio]] |

|||

[[fo:Bænadikt frá Nursia]] |

|||

[[fr:Benoît de Nursie]] |

|||

[[gl:Bieito de Nursia]] |

|||

[[ko:누르시아의 베네딕토]] |

|||

[[hr:Sveti Benedikt]] |

|||

[[id:Benedict dari Nursia]] |

|||

[[is:Benedikt frá Núrsíu]] |

|||

[[it:San Benedetto da Norcia]] |

|||

[[he:בנדיקטוס מנורסיה]] |

|||

[[la:Benedictus de Nursia]] |

|||

[[hu:Nursiai Szent Benedek]] |

|||

[[nl:Benedictus van Nursia]] |

|||

[[ja:ベネディクトゥス]] |

|||

[[pl:Benedykt z Nursji]] |

|||

[[pt:Bento de Núrsia]] |

|||

[[ru:Бенедикт Нурсийский]] |

|||

[[sq:Shën Benedikti i Nursisë]] |

|||

[[sk:Benedikt z Nursie]] |

|||

[[sr:Преподобни Бенедикт]] |

|||

[[fi:Benedictus Nursialainen]] |

|||

[[sv:Benedikt av Nursia]] |

|||

[[tr:Benedict (Norcialı)]] |

|||

[[uk:Бенедикт Святий]] |

|||

[[zh:圣本笃]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 01:33, 15 May 2024

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2023) |

Benedict of Nursia | |

|---|---|

A portrait of Saint Benedict as depicted in the Benedetto Portinari Triptych, by Hans Memling | |

| Founder of the Benedictine Order, Exorcist, Mystic, Abbot of Monte Cassino, and Father of Western Monasticism | |

| Born | 2 March 480 Nursia, Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | 21 March 547 (aged 67) Mons Casinus, Eastern Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | All Christian denominations which venerate saints |

| Canonized | 1220, Rome, Papal States by Pope Honorius III |

| Major shrine | Monte Cassino Abbey, with his burial Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, near Orléans, France |

| Feast | 11 July (General Roman Calendar, Lutheran Churches, Anglican Communion) 14 March (Eastern Orthodox Church) 21 March (pre-1970 General Roman Calendar) |

| Attributes |

|

| Patronage |

|

Benedict of Nursia OSB (Latin: Benedictus Nursiae; Italian: Benedetto da Norcia; 2 March AD 480 – 21 March AD 547), often known as Saint Benedict, was an Italian Christian monk, writer, and theologian. He is venerated in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, the Lutheran Churches, the Anglican Communion, and Old Catholic Churches.[3][4] In 1964 Pope Paul VI declared Benedict a patron saint of Europe.[5]

Benedict founded twelve communities for monks at Subiaco in present-day Lazio, Italy (about 65 kilometres (40 mi) to the east of Rome), before moving further south-east to Monte Cassino in the mountains of central Italy. The present-day Order of Saint Benedict emerged later and, moreover, is not an "order" as the term is commonly understood, but a confederation of autonomous congregations.[6]

Benedict's main achievement, his Rule of Saint Benedict, contains a set of rules for his monks to follow. Heavily influenced by the writings of John Cassian (c. 360 – c. 435), it shows strong affinity with the earlier Rule of the Master, but it also has a unique spirit of balance, moderation and reasonableness (ἐπιείκεια, epieíkeia), which persuaded most Christian religious communities founded throughout the Middle Ages to adopt it. As a result, Benedict's Rule became one of the most influential religious rules in Western Christendom. For this reason, Giuseppe Carletti regarded Benedict as the founder of Western Christian monasticism.[7]

Biography[edit]

Apart from a short poem attributed to Mark of Monte Cassino,[8] the only ancient account of Benedict is found in the second volume of Pope Gregory I's four-book Dialogues, thought to have been written in 593,[9] although the authenticity of this work is disputed.[10]

Gregory's account of Benedict's life, however, is not a biography in the modern sense of the word. It provides instead a spiritual portrait of the gentle, disciplined abbot. In a letter to Bishop Maximilian of Syracuse, Gregory states his intention for his Dialogues, saying they are a kind of floretum (an anthology, literally, 'flowers') of the most striking miracles of Italian holy men.[11]

Gregory did not set out to write a chronological, historically anchored story of Benedict, but he did base his anecdotes on direct testimony. To establish his authority, Gregory explains that his information came from what he considered the best sources: a handful of Benedict's disciples who lived with him and witnessed his various miracles. These followers, he says, are Constantinus, who succeeded Benedict as Abbot of Monte Cassino, Honoratus, who was abbot of Subiaco when St. Gregory wrote his Dialogues, Valentinianus, and Simplicius.

In Gregory's day, history was not recognised as an independent field of study; it was a branch of grammar or rhetoric, and historia was an account that summed up the findings of the learned when they wrote what was, at that time, considered history.[12] Gregory's Dialogues, Book Two, then, an authentic medieval hagiography cast as a conversation between the Pope and his deacon Peter,[a] is designed to teach spiritual lessons.[9]

Early life[edit]

He was the son of a Roman noble of Nursia,[9][13] the modern Norcia, in Umbria. If 480 is accepted as the year of his birth, the year of his abandonment of his studies and leaving home would be about 500. Gregory's narrative makes it impossible to suppose him younger than 20 at the time.

Benedict was sent to Rome to study, but was disappointed by urban academic life. Seeking to escape the great city, he left with his servant and settled in Enfide.[14] Enfide, which the tradition of Subiaco identifies with the modern Affile, is in the Simbruini mountains, about forty miles from Rome[13] and two miles from Subiaco.

A short distance from Enfide is the entrance to a narrow, gloomy valley, penetrating the mountains and leading directly to Subiaco. The path continues to ascend, and the side of the ravine on which it runs becomes steeper until a cave is reached, above this point the mountain now rises almost perpendicularly; while on the right, it strikes in a rapid descent down to where, in Benedict's day, 500 feet (150 m) below, lay the blue waters of a lake. The cave has a large triangular-shaped opening and is about ten feet deep. On his way from Enfide, Benedict met a monk, Romanus of Subiaco, whose monastery was on the mountain above the cliff overhanging the cave. Romanus discussed with Benedict the purpose which had brought him to Subiaco, and gave him the monk's habit. By his advice Benedict became a hermit and for three years lived in this cave above the lake.[13]

Later life[edit]

Gregory tells little of Benedict's later life. He now speaks of Benedict no longer as a youth (puer), but as a man (vir) of God. Romanus, Gregory states, served Benedict in every way he could. The monk apparently visited him frequently, and on fixed days brought him food.[14]

During these three years of solitude, broken only by occasional communications with the outer world and by the visits of Romanus, Benedict matured both in mind and character, in knowledge of himself and of his fellow-man, and at the same time he became not merely known to, but secured the respect of, those about him; so much so that on the death of the abbot of a monastery in the neighbourhood (identified by some with Vicovaro), the community came to him and begged him to become its abbot. Benedict was acquainted with the life and discipline of the monastery, and knew that "their manners were diverse from his and therefore that they would never agree together: yet, at length, overcome with their entreaty, he gave his consent".[10]: 3 The experiment failed; the monks tried to poison him. The legend goes that they first tried to poison his drink. He prayed a blessing over the cup and the cup shattered. Thus he left the group and went back to his cave at Subiaco.

There lived in the neighborhood a priest called Florentius who, moved by envy, tried to ruin him. He tried to poison him with poisoned bread. When he prayed a blessing over the bread, a raven swept in and took the loaf away. From this time his miracles seem to have become frequent, and many people, attracted by his sanctity and character, came to Subiaco to be under his guidance. Having failed by sending him poisonous bread, Florentius tried to seduce his monks with some prostitutes. To avoid further temptations, in about 530 Benedict left Subiaco.[15] He founded 12 monasteries in the vicinity of Subiaco, and, eventually, in 530 he founded the great Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino, which lies on a hilltop between Rome and Naples.[16]

Veneration[edit]

Benedict died of a fever at Monte Cassino not long after his sister, Scholastica, and was buried in the same tomb. According to tradition, this occurred on 21 March 547.[17] He was named patron protector of Europe by Pope Paul VI in 1964.[18] In 1980, Pope John Paul II declared him co-patron of Europe, together with Cyril and Methodius.[19] Furthermore, he is the patron saint of speleologists.[20] On the island of Tenerife (Spain) he is the patron saint of fields and farmers. An important romeria (Romería Regional de San Benito Abad) is held on this island in his honor, one of the most important in the country.[21]

In the pre-1970 General Roman Calendar, his feast is kept on 21 March, the day of his death according to some manuscripts of the Martyrologium Hieronymianum and that of Bede. Because on that date his liturgical memorial would always be impeded by the observance of Lent, the 1969 revision of the General Roman Calendar moved his memorial to 11 July, the date that appears in some Gallic liturgical books of the end of the 8th century as the feast commemorating his birth (Natalis S. Benedicti). There is some uncertainty about the origin of this feast.[22] Accordingly, on 21 March the Roman Martyrology mentions in a line and a half that it is Benedict's day of death and that his memorial is celebrated on 11 July, while on 11 July it devotes seven lines to speaking of him, and mentions the tradition that he died on 21 March.[23]

The Eastern Orthodox Church commemorates Saint Benedict on 14 March.[24]

The Lutheran Churches celebrate the Feast of Saint Benedict on July 11.[4]

The Anglican Communion has no single universal calendar, but a provincial calendar of saints is published in each province. In almost all of these, Saint Benedict is commemorated on 11 July. Benedict is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 11 July.[25]

Rule of Saint Benedict[edit]

Benedict wrote the Rule for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot. The Rule comprises seventy-three short chapters. Its wisdom is twofold: spiritual (how to live a Christocentric life on earth) and administrative (how to run a monastery efficiently).[16] More than half of the chapters describe how to be obedient and humble, and what to do when a member of the community is not. About one-fourth regulate the work of God (the "opus Dei"). One-tenth outline how, and by whom, the monastery should be managed. Benedictine asceticism is known for its moderation.[26]

Saint Benedict Medal[edit]

This devotional medal originally came from a cross in honor of Saint Benedict. On one side, the medal has an image of Saint Benedict, holding the Holy Rule in his left hand and a cross in his right. There is a raven on one side of him, with a cup on the other side of him. Around the medal's outer margin are the words "Eius in obitu nostro praesentia muniamur" ("May we be strengthened by his presence in the hour of our death"). The other side of the medal has a cross with the initials CSSML on the vertical bar which signify "Crux Sacra Sit Mihi Lux" ("May the Holy Cross be my light") and on the horizontal bar are the initials NDSMD which stand for "Non-Draco Sit Mihi Dux" ("Let not the dragon be my guide"). The initials CSPB stand for "Crux Sancti Patris Benedicti" ("The Cross of the Holy Father Benedict") and are located on the interior angles of the cross. Either the inscription "PAX" (Peace) or the Christogram "IHS" may be found at the top of the cross in most cases. Around the medal's margin on this side are the Vade Retro Satana initials VRSNSMV which stand for "Vade Retro Satana, Nonquam Suade Mihi Vana" ("Begone Satan, do not suggest to me thy vanities") then a space followed by the initials SMQLIVB which signify "Sunt Mala Quae Libas, Ipse Venena Bibas" ("Evil are the things thou profferest, drink thou thine own poison").[27]

This medal was first struck in 1880 to commemorate the fourteenth centenary of Benedict's birth and is also called the Jubilee Medal; its exact origin, however, is unknown. In 1647, during a witchcraft trial at Natternberg near Metten Abbey in Bavaria, the accused women testified they had no power over Metten, which was under the protection of the cross. An investigation found a number of painted crosses on the walls of the abbey with the letters now found on St Benedict medals, but their meaning had been forgotten. A manuscript written in 1415 was eventually found that had a picture of Benedict holding a scroll in one hand and a staff which ended in a cross in the other. On the scroll and staff were written the full words of the initials contained on the crosses. Medals then began to be struck in Germany, which then spread throughout Europe. This medal was first approved by Pope Benedict XIV in his briefs of 23 December 1741 and 12 March 1742.[27]

Benedict has been also the motif of many collector's coins around the world. The Austria 50 euro 'The Christian Religious Orders', issued on 13 March 2002 is one of them.

Influence[edit]

The early Middle Ages have been called "the Benedictine centuries."[28] In April 2008, Pope Benedict XVI discussed the influence St Benedict had on Western Europe. The pope said that "with his life and work St Benedict exercised a fundamental influence on the development of European civilization and culture" and helped Europe to emerge from the "dark night of history" that followed the fall of the Roman empire.[29]

Benedict contributed more than anyone else to the rise of monasticism in the West. His Rule was the foundational document for thousands of religious communities in the Middle Ages.[30] To this day, The Rule of St. Benedict is the most common and influential Rule used by monasteries and monks, more than 1,400 years after its writing.

A basilica was built upon the birthplace of Benedict and Scholastica in the 1400s. Ruins of their familial home were excavated from beneath the church and preserved. The earthquake of 30 October 2016 completely devastated the structure of the basilica, leaving only the front facade and altar standing.[31][32]

Gallery[edit]

- See also Category:Paintings of Benedict of Nursia.

-

Saint Benedict and the cup of poison (Melk Abbey, Austria)

-

Small gold-coloured Saint Benedict crucifix

-

Both sides of a Saint Benedict Medal

-

Portrait (1926) by Herman Nieg (1849–1928); Heiligenkreuz Abbey, Austria

-

St. Benedict at the Death of St. Scholastica (c. 1250–60), Musée National de l'Age Médiévale, Paris, orig. at the Abbatiale of St. Denis

-

Statue in Einsiedeln, Switzerland

-

Benedict holding a bound bundle of sticks representing the strength of monks who live in community[33]

See also[edit]

- Anthony the Great

- Scholastica (St. Benedict's sister)

- Benedict of Aniane

- Benedictine Order

- Camaldolese

- Hermit

- San Beneto

- Saint Benedict Medal

- Vade retro satana

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ For the various literary accounts, see Anonymous Monk of Whitby, The Earliest Life of Gregory the Great, tr. B. Colgrave (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), p. 157, n. 110.

Citations[edit]

- ^

Lanzi, Fernando; Lanzi, Gioia (2004) [2003]. Saints and Their Symbols: Recog [Come riconoscere i santi]. Translated by O'Connell, Matthew J. Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press. p. 218. ISBN 9780814629703. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

Benedict of Nursia [...] Principal attributes: black monastic garb, staff, book with inscription: "Pray and Work."

- ^ "Saint Benedict of Nursia: The Iconography". Archived from the original on 27 November 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Barry, Patrick (1995). St. Benedict and Christianity in England. Gracewing Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 9780852443385.

- ^ a b Ramshaw, Gail (1983). Festivals and Commemorations in Evangelical Lutheran Worship (PDF). Augsburg Fortress. p. 299.

- ^

Barrely, Christine; Leblon, Saskia; Péraudin, Laure; Trieulet, Stéphane (23 March 2011) [2009]. "Benedict". The Little Book of Saints [Petit livre des saints]. Translated by Bell, Elizabeth. San Francisco: Chronicle Book. p. 34. ISBN 9780811877473. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

Declared the patron saint of Europe in 1964 by Pope Paul VI, Benedict is also the patron of farmers, peasants, and Italian architects.

- ^ Holder, Arthur G. (2009). Christian Spirituality: The Classics. Taylor & Francis. p. 70. ISBN 9780415776028. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

Today, tens of thousands of men and women throughout the world profess to live their lives according to Benedict's Rule. These men and women are associated with over two thousand Roman Catholic, Anglican, and ecumenical Benedictine monasteries on six continents.

- ^ Carletti, Giuseppe, Life of St. Benedict (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1971).

- ^ "The Autumn Number 1921" (PDF). The Ampleforth Journal. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b c "Ford, Hugh. "St. Benedict of Norcia." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 3 Mar. 2014". Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ a b Life and Miracles of St. Benedict (Book II, Dialogues), tr. Odo John Zimmerman, O.S.B. and Benedict , O.S.B. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980), p. iv.

- ^ See Ildephonso Schuster, Saint Benedict and His Times, Gregory A. Roettger, tr. (London: B. Herder, 1951), p. 2.

- ^ See Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis, ed., Historiography in the Middle Ages (Boston: Brill, 2003), pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c Knowles, Michael David. "St. Benedict". Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ a b ""Saint Benedict, Abbot", Lives of Saints, John J. Crawley & Co., Inc". Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Bunson, M., Bunson, M., & Bunson, S., Our Sunday Visitor's Encyclopedia of Saints (Huntington IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 2014), p. 125.

- ^ a b "St Benedict of Nursia", the British Library