Octavia E. Butler: Difference between revisions

Corrected minor spelling mistake in "Novels" section. |

more about bloodchild, probably too much |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Octavia Estelle Butler''' ([[June 22]], [[1947]] – [[February 24]], [[2006]]) was an [[United States|American]] [[science fiction]] [[writer]], one of very few [[African-American]] women in the field. She won both [[Hugo award|Hugo]] and [[Nebula award|Nebula]] awards. In 1995, she became the first science fiction writer to receive the [[MacArthur Fellows Program|MacArthur Foundation "Genius" Grant]]. |

'''Octavia Estelle Butler''' ([[June 22]], [[1947]] – [[February 24]], [[2006]]) was an [[United States|American]] [[science fiction]] [[writer]], one of very few [[African-American]] women in the field. She won both [[Hugo award|Hugo]] and [[Nebula award|Nebula]] awards. In 1995, she became the first (and as of 2003 only) science fiction writer to receive the [[MacArthur Fellows Program|MacArthur Foundation "Genius" Grant]].<ref name="kindafter1">{{cite conference |

||

| first = Robert |

|||

| last = Crossley |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

| coauthors = |

|||

| title = Critical Essay |

|||

| booktitle = Kindred: 25th Anniversary Edition |

|||

| pages = |

|||

| publisher = [[Beacon Press]] |

|||

| date = 2003 |

|||

| location = Boston |

|||

| url = |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| id = |

|||

| accessdate = }}</ref> |

|||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

Butler was born and raised in [[Pasadena, California|Pasadena]], [[California]]. Since her father Laurice, a shoeshiner, died when she was a baby, Butler was raised by her grandmother and her mother ( |

Butler was born and raised in [[Pasadena, California|Pasadena]], [[California]]. Since her father Laurice, a shoeshiner, died when she was a baby, Butler was raised by her grandmother and her mother (Octavia M. Butler) who worked as a maid in order to support the family. Butler grew up in a struggling, racially mixed neighborhood.<ref>[http://www.aaregistry.com/african_american_history/1732/Octavia_Butler_a_unique_writer AA Registry.com profile on Octavia Butler].</ref> According to the ''[[W. W. Norton|Norton Anthology of African American Literature]]'', Butler was "an introspective only child in a strict Baptist household" and "was drawn early to magazines such as ''Amazing'', ''Fantasy and Science Fiction'', and ''Galaxy'' and soon began reading all the science fiction classics."<ref>''Norton Anthology of African American Literature'', p.2515.</ref> |

||

Octavia Jr., nicknamed Junie, was paralytically shy and a daydreamer, and was later diagnosed as being [[dyslexia|dyslexic]]. She began writing at the age of 10 "to escape loneliness and boredom"; she was 12 when she began a lifelong interest in science fiction.<ref>[http://voices.cla.umn.edu/vg/Bios/entries/butler_octavia_estelle.html Voices].</ref> "I was writing my own little stories and when I was 12, I was watching a bad science fiction movie called ''[[Devil Girl from Mars]]''", she told the journal ''Black Scholar'', "and decided that I could write a better story than that. And I turned off the TV and proceeded to try, and I've been writing science fiction ever since."<ref>[http://www.geocities.com/sela_towanda/essay.htm Essay].</ref> |

Octavia Jr., nicknamed Junie, was paralytically shy and a daydreamer, and was later diagnosed as being [[dyslexia|dyslexic]]. She began writing at the age of 10 "to escape loneliness and boredom"; she was 12 when she began a lifelong interest in science fiction.<ref>[http://voices.cla.umn.edu/vg/Bios/entries/butler_octavia_estelle.html Voices].</ref> "I was writing my own little stories and when I was 12, I was watching a bad science fiction movie called ''[[Devil Girl from Mars]]''", she told the journal ''Black Scholar'', "and decided that I could write a better story than that. And I turned off the TV and proceeded to try, and I've been writing science fiction ever since."<ref>[http://www.geocities.com/sela_towanda/essay.htm Essay].</ref> |

||

| Line 43: | Line 56: | ||

==Career== |

==Career== |

||

Her first published story, "Crossover," appeared in Clarion's 1971 anthology; another short story, "Childfinder," was bought by [[Harlan Ellison]] for the never-published collection ''[[The Last Dangerous Visions]]''. (Like other stories purchased for that volume, it has yet to appear anywhere.) "I thought I was on my way as a writer |

Her first published story, "Crossover," appeared in Clarion's 1971 anthology; another short story, "Childfinder," was bought by [[Harlan Ellison]] for the never-published collection ''[[The Last Dangerous Visions]]''. (Like other stories purchased for that volume, it has yet to appear anywhere.) "I thought I was on my way as a writer..." Butler wrote in her short fiction collection ''Bloodchild and Other Stories''. "In fact, I had five more years of rejections slips and horrible little jobs ahead of me before I sold another word."<ref name="crossover">{{Citation |

||

| last = Butler |

|||

| first = Octavia E. |

|||

| author-link = |

|||

| last2 = |

|||

| first2 = |

|||

| author2-link = |

|||

| title = Bloodchild and Other Stories |

|||

| place= |

|||

| publisher = Seven Stories Press |

|||

| year = 2005 |

|||

| location = New York, NY |

|||

| volume = |

|||

| edition = second |

|||

| url = |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| id = |

|||

| pages = 120 |

|||

| isbn = }}</ref> |

|||

===''Patternist'' series=== |

===''Patternist'' series=== |

||

| Line 65: | Line 96: | ||

===Short stories=== |

===Short stories=== |

||

Butler published one collection of her shorter writings, ''Bloodchild and Other Stories'', in 1996. She states in the preface that she "hate[s] short story writing" and that she is "essentially a novelist. The ideas that most interest me tend to be big."<ref name="bloodpref">{{Citation |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| last = Butler |

|||

| first = Octavia E. |

|||

| author-link = |

|||

| last2 = |

|||

| first2 = |

|||

| author2-link = |

|||

| title = Bloodchild and Other Stories |

|||

| place= |

|||

| publisher = Seven Stories Press |

|||

| year = 2005 |

|||

| location = New York, NY |

|||

| volume = |

|||

| edition = second |

|||

| url = |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| id = |

|||

| pages = vii-viii |

|||

| ⚫ | | isbn = }}</ref> The collection includes five short stories spanning Butler's career, the first finished in 1971 and the last in 1993. ''Bloodchild'', the Hugo and Nebula award-winning title story, concerns humans who live on a reservation on an alien planet ruled by insect-like creatures. The worm-creatures breed by implanting eggs in the humans, with whom they share a [[symbiotic]] existence. In Butler's afterword to the story, she writes that it is not about slavery as some have suggested, but rather about love and coming-of-age--as well as male pregnancy and the "unusual accomodation[s]" that a group of interstellar colonists might have to make with their adopted planet's prior inhabitants.<ref name="bloodaft">{{Citation |

||

| last = Butler |

|||

| first = Octavia E. |

|||

| author-link = |

|||

| last2 = |

|||

| first2 = |

|||

| author2-link = |

|||

| title = Bloodchild and Other Stories |

|||

| place= |

|||

| publisher = Seven Stories Press |

|||

| year = 2005 |

|||

| location = New York, NY |

|||

| volume = |

|||

| edition = second |

|||

| url = |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| id = |

|||

| pages = 30-32 |

|||

| isbn = }}</ref> |

|||

She also states that writing it was her way of overcoming a fear of [[bot fly|bot flies]].<ref name="bloodaft" /> |

|||

In 2005, [[Seven Stories Press]] released an expanded edition. |

In 2005, [[Seven Stories Press]] released an expanded edition. |

||

| Line 151: | Line 219: | ||

*Schwab, Gabriele. "Ethnographies of the Future: Personhood, Agency and Power in Octavia Butler's ''Xenogenesis''." In ''Accelerating Possession'', William Maurer and Gabriele Schwab (eds.). New York: Columbia UP, 2006: 204-228. |

*Schwab, Gabriele. "Ethnographies of the Future: Personhood, Agency and Power in Octavia Butler's ''Xenogenesis''." In ''Accelerating Possession'', William Maurer and Gabriele Schwab (eds.). New York: Columbia UP, 2006: 204-228. |

||

*Scott, Johnathan. "Octavia Butler and the Base for American Socialism" In ''Socialism and Democracy'' 20.3 November 2006, 105-126 |

*Scott, Johnathan. "Octavia Butler and the Base for American Socialism" In ''Socialism and Democracy'' 20.3 November 2006, 105-126 |

||

*Slonczewski, Joan, ‘Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis Trilogy: A Biologist’s Response’ [http://biology.kenyon.edu/slonc/books/butler1.html] |

*[[Joan Slonczewski|Slonczewski, Joan]], ‘Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis Trilogy: A Biologist’s Response’ [http://biology.kenyon.edu/slonc/books/butler1.html] |

||

====Citations==== |

====Citations==== |

||

Revision as of 06:52, 15 September 2007

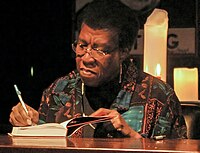

Octavia Estelle Butler | |

|---|---|

Butler signing a copy of Fledgling | |

| Born | June 22, 1947 Pasadena, California |

| Died | February 24, 2006 (aged 58) Seattle, Washington |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | United States |

| Period | 1970s–2000s |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Website | |

| http://www.sfwa.org/members/butler/Index.html | |

Octavia Estelle Butler (June 22, 1947 – February 24, 2006) was an American science fiction writer, one of very few African-American women in the field. She won both Hugo and Nebula awards. In 1995, she became the first (and as of 2003 only) science fiction writer to receive the MacArthur Foundation "Genius" Grant.[1]

Biography

Butler was born and raised in Pasadena, California. Since her father Laurice, a shoeshiner, died when she was a baby, Butler was raised by her grandmother and her mother (Octavia M. Butler) who worked as a maid in order to support the family. Butler grew up in a struggling, racially mixed neighborhood.[2] According to the Norton Anthology of African American Literature, Butler was "an introspective only child in a strict Baptist household" and "was drawn early to magazines such as Amazing, Fantasy and Science Fiction, and Galaxy and soon began reading all the science fiction classics."[3]

Octavia Jr., nicknamed Junie, was paralytically shy and a daydreamer, and was later diagnosed as being dyslexic. She began writing at the age of 10 "to escape loneliness and boredom"; she was 12 when she began a lifelong interest in science fiction.[4] "I was writing my own little stories and when I was 12, I was watching a bad science fiction movie called Devil Girl from Mars", she told the journal Black Scholar, "and decided that I could write a better story than that. And I turned off the TV and proceeded to try, and I've been writing science fiction ever since."[5]

After getting an associate degree from Pasadena City College in 1968 [1], she next enrolled at California State University, Los Angeles. She eventually left CalState and took writing classes through UCLA extension.

Butler would later credit two writing workshops for giving her "the most valuable help I received with my writing" [2]:

- 1969–1970: The Open Door Workshop of the Screenwriters' Guild of America, West, a program "designed to mentor Latino and African-American writers". Through Open Door she met the noted science fiction writer Harlan Ellison.

- 1970: The Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop, (introduced to her by Ellison), where she first met Samuel R. Delany[6]

Butler moved to Seattle, Washington, in November 1999.

She described herself as "comfortably asocial—a hermit in the middle of Seattle—a pessimist if I'm not careful, a feminist, a Black, a former Baptist, an oil-and-water combination of ambition, laziness, insecurity, certainty, and drive."[7] Themes of both racial and sexual ambiguity are apparent throughout her work.

She died outside of her home on February 24 2006, at the age of 58. Some news accounts have stated that she died of head injuries after falling and striking her head on her walkway, while others report that she apparently suffered a stroke.

Career

Her first published story, "Crossover," appeared in Clarion's 1971 anthology; another short story, "Childfinder," was bought by Harlan Ellison for the never-published collection The Last Dangerous Visions. (Like other stories purchased for that volume, it has yet to appear anywhere.) "I thought I was on my way as a writer..." Butler wrote in her short fiction collection Bloodchild and Other Stories. "In fact, I had five more years of rejections slips and horrible little jobs ahead of me before I sold another word."[8]

Patternist series

In 1974, she started the novel Patternmaster (reportedly related to the story she started after watching Devil Girl from Mars), which became her first published book in 1976 (though it would become the fifth in the Patternist series). Over the next eight years, she would publish four more novels in the same story line, though the publication dates of the novels do not match the internal order of the series (see Works below).

Kindred

In 1979, she published Kindred, a novel that uses the science-fiction technique of time travel to explore slavery in the United States. In this story, Dana, an African American woman, is taken from 1976 to turn-of-the-19th-century ante-bellum South. She meets her ancestors, Rufus, a white slave holder; and Alice, an African American woman who was born free but forced into slavery later in life.

This novel is often shelved in the literature or African-American literature sections of bookstores instead of science fiction—Butler herself categorized the novel not as science fiction but rather as a "grim fantasy"—Kindred became the most popular of all her books, with 250,000 copies currently in print. "I think people really need to think what it's like to have all of society arrayed against you," she said of the novel.[9]

Xenogenesis

Butler began her Xenogenesis trilogy in 1987. The central characters are Lilith and her genetically altered children. Lilith, along with the few other surviving humans, are abducted by extraterrestrials, the Oankali, after a "handful of people [a military group] tried to commit humanicide," leading to a missile war that destroyed much of Earth. The Oankali have a third gender, the ooloi, who have the ability to manipulate genetics, plus the ability of sexually seductive neural-stimulating and consciousness-sharing powers. All of these abilities allow them to unify the other two genders in their species, as well as unifying their species with others that they encounter. The Oankali are biological traders, driven to share genes with other intelligent species, changing both parties. The entire series, Dawn, Adulthood Rites, and Imago, was released in 2000 as the single volume titled Lilith's Brood.

The Parable series

In 1994, her dystopian novel Parable of the Sower was nominated for a Nebula for best novel, an award she finally took home in 1999 for a sequel, Parable of the Talents. The two novels provide the origin of the fictional religion Earthseed.

Butler had originally planned to write a third Parable novel, tentatively titled Parable of the Trickster, mentioning her work on it in a number of interviews, but at some point encountered a form of writer's block, going seven years without publishing a new novel.

Fledgling

She eventually shifted her creative attention, resulting in the 2005 novel, Fledgling, a vampire novel with a science-fiction context. Although Butler herself passed Fledgling off as a lark, the novel is connected to her other works through its exploration of race, sexuality, and what it means to be a member of a community. Moreover, the novel continues the theme, raised explicitly in Parable of the Sower, that diversity is a biological imperative.

Short stories

Butler published one collection of her shorter writings, Bloodchild and Other Stories, in 1996. She states in the preface that she "hate[s] short story writing" and that she is "essentially a novelist. The ideas that most interest me tend to be big."[10] The collection includes five short stories spanning Butler's career, the first finished in 1971 and the last in 1993. Bloodchild, the Hugo and Nebula award-winning title story, concerns humans who live on a reservation on an alien planet ruled by insect-like creatures. The worm-creatures breed by implanting eggs in the humans, with whom they share a symbiotic existence. In Butler's afterword to the story, she writes that it is not about slavery as some have suggested, but rather about love and coming-of-age--as well as male pregnancy and the "unusual accomodation[s]" that a group of interstellar colonists might have to make with their adopted planet's prior inhabitants.[11] She also states that writing it was her way of overcoming a fear of bot flies.[11]

In 2005, Seven Stories Press released an expanded edition.

Series

Butler is well known for her Patternist series, Xenogenesis Trilogy, and the Parable of the Sower Series. The first book which she wrote for the Patternist series, Patternmaster (1976), is actually the last in the internal chronology of the series. In fact, most of the Patternmaster novels were written and published out of sequence. Her Xenogenesis series was released in 2000 as the single volume, Lilith's Brood. The four novels in Butler's "Patternist series" other than Survivor will be released in 2007 as the single volume, Seed to Harvest.

Awards

Winner:

- 2000: lifetime achievement award in writing from the PEN American Center

- 1999: Nebula Award for Best Novel - Parable of the Talents

- 1995: MacArthur Foundation "Genius" Grant

- 1985: Hugo Award for Best Novelette - Bloodchild

- 1985: Locus Award for Best Novelette - "Bloodchild"[12]

- 1985: Science Fiction Chronicle Award for Best Novelette - "Bloodchild"[13]

- 1984: Nebula Award for Best Novelette - Bloodchild

- 1984: Hugo Award for Best Short Story - Speech Sounds

- 1980: Creative Arts Award, L.A. YWCA

Nominated:

- 1994: Nebula Award for Best Novel - Parable of the Sower

- 1987: Nebula Award for Best Novelette - The Evening and the Morning and the Night

- 1967: Fifth Place, Writer's Digest Short Story Contest

Scholarship Fund

The Octavia E. Butler Memorial Scholarship was established in Ms. Butler's memory in 2006 by the Carl Brandon Society. Its goal is to provide an annual scholarship to enable writers of color to attend one of the Clarion writing workshops where Ms. Butler got her start. The first scholarships were awarded in 2007.

Works

Novels

Series

- Patternist series

- Patternmaster (1976)

- Mind of My Mind (1977)

- Survivor (1978)

- Wild Seed (1980)

- Clay's Ark (1984)

- Seed to Harvest (compilation; 2007)

- Xenogenesis Trilogy

- Dawn (1987)

- Adulthood Rites (1988)

- Imago (1989)

- Lilith's Brood (compilation, 2000)

- Parable of the Sower Series

- Parable of the Sower (1993)

- Parable of the Talents (1998)

Other Fiction

- Bloodchild and Other Stories (1995); Second edition with additional stories (2006)

Articles

- A Few Rules For Predicting The Future - science-fiction author Octavia E. Butler - Essence (magazine)

- AHA! MOMENT-Eye Witness: Octavia Butler - oprah.com

See also

- Afrofuturism

- List of famous tall women

- List of science fiction authors

- Oankali

- Ooloi

- Women science fiction authors

Notes

- ^ Crossley, Robert (2003). "Critical Essay". Kindred: 25th Anniversary Edition. Boston: Beacon Press.

{{cite conference}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ AA Registry.com profile on Octavia Butler.

- ^ Norton Anthology of African American Literature, p.2515.

- ^ Voices.

- ^ Essay.

- ^ Washington Post obituary, 2006/2/27.

- ^ TW Bookmark.

- ^ Butler, Octavia E. (2005), Bloodchild and Other Stories (second ed.), New York, NY: Seven Stories Press, p. 120

- ^ Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- ^ Butler, Octavia E. (2005), Bloodchild and Other Stories (second ed.), New York, NY: Seven Stories Press, pp. vii–viii

- ^ a b Butler, Octavia E. (2005), Bloodchild and Other Stories (second ed.), New York, NY: Seven Stories Press, pp. 30–32

- ^ 1985 Locus Awards

- ^ Science Fiction Chronicle Reader Awards Winners By Year

References

Biographies

- Gates, Henry Louis Jr (ed.). "Octavia Butler." In The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, 2nd Edition. New York: W.W. Norton and Co, 2004: 2515.

- Geyh, Paula, Fred G. Leebron and Andrew Levy. "Octavia Butler." In Postmodern American Fiction: A Norton Anthology. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1998: 554-555.

Scholarship

- Baccolini, Raffaella. "Gender and Genre in the Feminist Critical Dystopias of Katharine Burdekin, Margaret Atwood, and Octavia Butler." In Future Females, the Next Generation: New Voices and Velocities in Feminist Science Fiction Criticism, Marleen S. Barr (ed.). New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2000: 13-34.

- Haraway, Donna. "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century," and "The Biopolitics of Postmodern Bodies: Constitutions of Self in Immune System Discourse," in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991: 149-181, 203-230.

- Holden, Rebecca J., ‘The High Costs of Cyborg Survival: Octavia Butler's Xenogenesis Trilogy’, in Foundation: The International Review of Science Fiction 72 (1998): 49–56.

- Lennard, John. Octavia Butler: Xenogenesis / Lilith's Brood. Tirril: Humanities-Ebooks, 2007. ISBN 978-1-84760-036-3

- -- 'Of Organelles: The Strange Determination of Octavia Butler'. In Of Modern Dragons and other essays on Genre Fiction. Tirril: Humanities-Ebooks, 2007: 163-90. ISBN 978-1-84760-038-7

- Levecq, Christine, ‘Power and Repetition: Philosophies of (Literary) History in Octavia E. Butler's Kindred’, in Contemporary Literature 41.1 (2000 Spring): 525–53.

- Luckhurst, Roger, ‘'Horror and Beauty in Rare Combination': The Miscegenate Fictions of Octavia Butler’, in Women: A Cultural Review 7.1 (1996): 28–38.

- Melzer, Patricia, Alien Constructions: Science Fiction and Feminist Thought. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-292-71307-9

- Ramirez, Catherine S. "Cyborg Feminism: The Science Fiction of Octavia Butler and Gloria Anzaldua." In Reload: Rethinking Women and Cyberculture, Mary Flanagan and Austin Booth (eds.). Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002: 374-402.

- Schwab, Gabriele. "Ethnographies of the Future: Personhood, Agency and Power in Octavia Butler's Xenogenesis." In Accelerating Possession, William Maurer and Gabriele Schwab (eds.). New York: Columbia UP, 2006: 204-228.

- Scott, Johnathan. "Octavia Butler and the Base for American Socialism" In Socialism and Democracy 20.3 November 2006, 105-126

- Slonczewski, Joan, ‘Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis Trilogy: A Biologist’s Response’ [3]

Citations

External links

Biographies and works

- Octavia Butler homepage from Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America

- Voices from the Gaps: Octavia Estelle Butler; biography.

- Bibliography from Feminist Sci Fi Utopia

- Octavia E. Butler at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database; bibliography.

- Octavia E. Butler Memorial Scholarship, administered by the Carl Brandon Society

- Octavia Butler.net; a fansite which includes rare content by and about Octavia Butler.

- "The Book of Martha" at Scifi.com

- "Amnesty" at Scifi.com

- Octavia Butler biography from Black Women in America at OUP Blog

- "Devil Girl From Mars": Why I Write Science Fiction, MIT Media in Transition Project, October 4 1998

- Strange Bedfellows: Eugenics, Attraction, and Aversion in the Works of Octavia E. Butler

- Profile in Marquis Who's Who on the Web

Interviews

- "Interview: Octavia Butler", scifidimensions, June 2004; on the 25th anniversary of Kindred.

- "Interview with Octavia Butler", The Indypendent, January 2006

- "Interview with Octavia Butler", Addicted to Race, February 6 2006.

- "Science Fiction Writer Octavia Butler on Race, Global Warming and Religion", Democracy Now!, November 11 2005.

- "Essay on Racism: A Science-Fiction Writer Shares Her View of Intolerance", Weekend Edition Saturday, September 1 2001.

- Interview with Locus magazine, June 2000

- The Bat Segundo Show #15 (podcast interview)

- 1947 births

- 2006 deaths

- Cause of death disputed

- California State University, Los Angeles alumni

- African American writers

- American novelists

- American science fiction writers

- American women writers

- Baptists

- Feminist writers

- Hugo Award winning authors

- Nebula Award winning authors

- MacArthur Fellows

- Washington writers

- People from Seattle

- LGBT people from the United States

- Lesbian writers