Pan (genus): Difference between revisions

m →See also: rm parenthetical "See also" |

|||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

* [[Chimpanzee Genome Project]] |

* [[Chimpanzee Genome Project]] |

||

* [[Laughter]] |

* [[Laughter]] |

||

* [[CCR5]] |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

Revision as of 00:49, 30 September 2007

| Chimpanzees[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Common Chimpanzee in Cameroon's South Province | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Tribe: | |

| Subtribe: | Panina

|

| Genus: | Pan Oken, 1816

|

| Type species | |

| Simia troglodytes Blumenbach, 1775

| |

| Species | |

| |

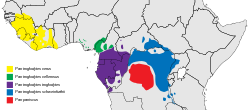

| distribution of Pan spp. | |

Chimpanzee, often shortened to chimp, is the common name for the two extant species in the genus Pan. The better known chimpanzee is Pan troglodytes, the Common Chimpanzee, living primarily in West, and Central Africa. Its cousin, the Bonobo or "Pygmy Chimpanzee" as it is known archaically, Pan paniscus, is found in the forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Congo River forms the boundary between the two species.[2] Chimpanzees are members of the Hominidae family, along with gorillas, humans, and orangutans.

Measurements

A full grown adult male chimpanzee can weigh from 35-70 kilograms (75-155 pounds) and stand 0.9-1.2 meters (3-4 feet) tall, while females usually weigh 26-50 kg (57-110 pounds) and stand 0.66-1 meters (2.0-3.5 feet) tall.

Lifespan

Chimpanzees rarely live past the age of 40 in the wild, but have been known to reach the age of 60 in captivity. Cheeta, star of Tarzan is still alive as of 2007 at the age of 75, making him the oldest known chimpanzee in the world.[3]

Chimpanzee differences

Anatomical differences between the Common Chimpanzee and the Bonobo are slight, but in sexual and social behaviour there are marked differences. Common Chimpanzees have an omnivorous diet, a troop hunting culture based on beta males led by an alpha male, and highly complex social relationships; Bonobos, on the other hand, have a mostly herbivorous diet and an egalitarian, matriarchal, sexually receptive behavior. The exposed skin of the face, hands and feet varies from pink to very dark in both species, but is generally lighter in younger individuals, darkening as maturity is reached. Bonobos have proportionately longer upper limbs and tend to walk upright more often than the Common Chimpanzee. A University of Chicago Medical Centre study has found significant genetic differences between chimpanzee populations[4]. Different groups of Chimpanzees also have different cultural behavior with preferences for types of tools.[5]

History of human interaction

Africans have had contact with chimpanzees for millennia. Chimpanzees have been kept as domesticated pets for centuries in a few African villages, especially in Congo. The first recorded contact of Europeans with chimps took place in present-day Angola during the 1600s. The diary of Portuguese explorer Duarte Pacheco Pereira (1506), preserved in the Portuguese National Archive (Torre do Tombo), is probably the first European document to acknowledge that chimpanzees built their own rudimentary tools.

The first use of the name "chimpanzee", however, did not occur until 1738. The name is derived from a Tshiluba language term "kivili-chimpenze", which is the local name for the animal and translates loosely as "mockman" or possibly just "ape". The colloquialism "chimp" was most likely coined some time in the late 1870s[citation needed]. Biologists applied Pan as the genus name of the animal. Chimps as well as other apes had also been purported to have been known to Western writers in ancient times, but mainly as myths and legends on the edge of Euro-Arabic societal consciousness, mainly through fragmented and sketchy accounts of European adventurers. Apes are mentioned variously by Aristotle, as well as the Bible.

When chimpanzees first began arriving on the European continent, European scientists noted the inaccuracy of these ancient descriptions, which often reported that chimpanzees had horns and hooves. The first of these early trans-continental chimpanzees came from Angola and were presented as a gift to Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange in 1640, and were followed by a few of its brethren over the next several years. Scientists who examined these rare specimens were baffled[citation needed], and described these first chimpanzees as "pygmies", and noted the animals' distinct similarities to humans. The next two decades would see a number of the creatures imported into Europe, mainly acquired by various zoological gardens as entertainment for visitors.

Darwin's theory of evolution (published in 1859) spurred scientific interest in chimpanzees, as in much of life science, leading eventually to numerous studies of the animals in the wild and captivity. The observers of chimpanzees at the time were mainly interested in behaviour as it related to that of humans. This was less strictly and disinterestedly scientific than it might sound, with much attention being focused on whether or not the animals had traits that could be considered 'good'; the intelligence of chimpanzees was often significantly exaggerated. At one point there was even a scheme drawn up to domesticate chimpanzees in order to have them perform various menial tasks (i.e. factory work)[citation needed]. By the end of the 1800s chimpanzees remained very much a mystery to humans, with very little factual scientific information available.

The 20th century saw a new age of scientific research into chimpanzee behaviour. Prior to 1960, almost nothing was known about chimpanzee behavior in their natural habitat. In July of that year, Jane Goodall set out to Tanzania's Gombe forest to live among the chimpanzees. Her discovery that chimpanzees made and used tools was groundbreaking, as humans were previously believed to be the only species to do so. The most progressive early studies on chimpanzees were spearheaded primarily by Wolfgang Köhler and Robert Yerkes, both of whom were renowned psychologists. Both men and their colleagues established laboratory studies of chimpanzees focused specifically on learning about the intellectual abilities of chimpanzees, particularly problem-solving. This typically involved basic, practical tests on laboratory chimpanzees, which required a fairly high intellectual capacity (such as how to solve the problem of acquiring an out-of-reach banana). Notably, Yerkes also made extensive observations of chimpanzees in the wild which added tremendously to the scientific understanding of chimpanzees and their behaviour. Yerkes studied chimpanzees until World War II, while Köhler concluded five years of study and published his famous Mentality of Apes in 1925 (which is coincidentally when Yerkes began his analyses), eventually concluding that "chimpanzees manifest intelligent behavior of the general kind familiar in human beings ... a type of behaviour which counts as specifically human" (1925).[6]

Common Chimpanzees have been known to attack humans on occasion.[7][8] There have been many attacks in Uganda by chimpanzees against human children; the results are sometimes fatal for the children. Some of these attacks are presumed to be due to chimpanzees being intoxicated (from alcohol obtained from rural brewing operations) and mistaking human children[9] for the Western Red Colobus, one of their favorite meals.[10] The dangers of careless human interactions with chimpanzees are only aggravated by the fact that many chimpanzees perceive humans as potential rivals,[11] and by the fact that the average chimpanzee has over 5 times the upper-body strength of a human male.[12] As a result virtually any angered chimpanzee can easily overpower and potentially kill even a fully grown man, as shown by the attack and near death of former NASCAR driver Saint James Davis.[13][14]

Studies of language

Scientists have long been fascinated with the studies of language, as it was potentially the most uniquely human cognitive ability. To test the hypothesis of the human-uniqueness of language, scientists have attempted to teach several species of great apes language. One early attempt was performed by Allen and Beatrice Gardner in the 1960s, in which they spent 51 months attempting to teach a chimpanzee named Washoe American Sign Language. Washoe reportedly learned 151 signs in those 51 months.[15] Over a longer period of time, Washoe reportedly learned over 800 signs.[16] Numerous other studies including one involving a chimpanzee named Nim Chimpsky have been conducted since with varying levels of success. There is ongoing debate among some scientists, notably Noam Chomsky and David Premack, about the great apes' ability to learn language.

Laughter in non-human apes

Laughter might not be confined or unique to humans, despite Aristotle's observation that "only the human animal laughs". The differences between chimpanzee and human laughter may be the result of adaptations that have evolved to enable human speech. Self-awareness of one's situation such as the monkey-mirror experiments below, or the ability to identify with another's predicament (see mirror neurons), are prerequisites for laughter, so animals may be laughing in the same way that we do.

Chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans show laughter-like vocalizations in response to physical contact, such as wrestling, play chasing, or tickling. This is documented in wild and captive chimpanzees. Chimpanzee laughter is not readily recognizable to humans as such, because it is generated by alternating inhalations and exhalations that sound more like breathing and panting. There are instances in which non-human primates have been reported to have expressed joy. One study analyzed and recorded sounds made by human babies and bonobos (also known as pygmy chimpanzees) when tickled. It found, that although the bonobo’s laugh was a higher frequency, the laugh followed a pattern similar to that of human babies to include similar facial expressions. Humans and chimpanzees share similar ticklish areas of the body, such as the armpits and belly. The enjoyment of tickling in chimpanzees does not diminish with age. Discovery 2003 A chimpanzee laughter sample. Goodall 1968 & Parr 2005

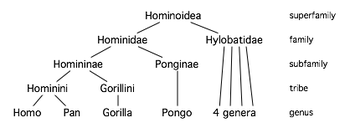

Taxonomic relationships

The genus Pan is now considered to be part of the subfamily Homininae to which humans also belong. Biologists believe that the two species of chimpanzees are the closest living evolutionary relatives to humans. It is thought that humans shared a common ancestor with chimpanzees as recently as four to seven million years ago.[citation needed] Groundbreaking research by Mary-Claire King in 1973 found 99% identical DNA between human beings and chimpanzees,[17] although research since has modified that finding to about 94%[18] commonality, with at least some of the difference occurring in 'junk' DNA. It has even been proposed that troglodytes and paniscus belong with sapiens in the genus Homo, rather than in Pan. One argument for this is that other species have been reclassified to belong to the same genus on the basis of less genetic similarity than that between humans and chimpanzees.

A study published by Clark and Nielsen of Cornell University in the December 2003 issue of the journal Science highlights differences related to one of humankind's defining qualities — the ability to understand language and to communicate through speech. These macro-phenotypic differences, however, may owe less to physiology than might be assumed given that Homo sapiens developed modern cultural features long after the modern physiological features were in place and indeed competed averagely against other species of Homo with regard to tools, etc for many millennia. Differences also exist in the genes for smell, in genes that regulate the metabolism of amino acids and in genes that may affect the ability to digest various proteins. See the history of hominoid taxonomy for more about the history of the classification of chimpanzees. See Human evolutionary genetics for more information on the speciation of humans and great apes.

Fossils

Many human fossils have been found, but chimpanzee fossils were not described until 2005. Existing chimpanzee populations in West and Central Africa do not overlap with the major human fossil sites in East Africa. However, chimpanzee fossils have now been reported from Kenya. This would indicate that both humans and members of the Pan clade were present in the East African Rift Valley during the Middle Pleistocene.[19]

Intelligence

Tool use

Modern chimpanzees use tools, and recent research indicates that chimpanzee stone tool use dates to at least 4300 years ago.[20] A recent study revealed the use of such advanced tools as spears, which Common Chimpanzees in Senegal sharpen with their teeth, being used to spear Senegal Bushbabies out of small holes in trees.[21][22] Several other species of animals are also known to use tools. Prior to the discovery of tool use in chimps, it was believed that humans were the only species to make and use tools, but several other tool-using species are now known.[23] [24]

Altruism

Recent studies have shown that chimpanzees engage in apparently altruistic behavior.[25][26]

Consequences of Chimpanzee intelligence

The high levels of intelligence and cognitive similarity to humans has caused some countries to enact a Great Ape research ban which forbids the use of chimpanzees or other great apes for scientific research.[27]

References

- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 182–183. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "ADW:Pan troglodytes:information". Animal Diversity Web (University of Michigan Museum of Zoology). Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ Moehringer, J.R. (2007-04-22). "Cheeta speaks". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Gene study shows three distinct groups of chimpanzees". EurekAlert. April 20 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Chimp Behavior". Jane Goodall Institute. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ Goodall, Jane (1986). The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. ISBN 0-674-11649-6.

- ^ Claire Osborn. "Texas man saves friend during fatal chimp attack". The Pulse Journal. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "Chimp attack kills cabbie and injures tourists". The Guardian. 2006-04-25. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "'Drunk and Disorderly' Chimps Attacking Ugandan Children". 2004-02-09. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ http://virus.stanford.edu/filo/eboci.html

- ^ "Chimp attack doesn't surprise experts". MSNBC. 2005-03-05. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Can a 90-lb. chimp clobber a full-grown man?". The Straight Dope. 1976-09-10. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Birthday party turns bloody when chimps attack". USATODAY. 2005-03-04. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ Amy Argetsinger (2005-05-24). "The Animal Within". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ Gardner, R. A., Gardner, B. T. (1969). "Teaching Sign Language to a Chimpanzee". Science. 165: 664–672.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Allen, G. R., Gardner, B. T. (1980). "Comparative psychology and language acquisition". In Thomas A. Sebok and Jean-Umiker-Sebok (eds.) (ed.). Speaking of Apes: A Critical Anthology of Two-Way Communication with Man. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 287–329.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mary-Claire King, Protein polymorphisms in chimpanzee and human evolution, Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley (1973).

- ^ "Humans and Chimps: Close But Not That Close". Scientific American. 2006-12-19. Retrieved 2006-12-20.

- ^ McBrearty, S. (2005-09-01). "First fossil chimpanzee". Nature. 437: 105–108. Template:Entrez Pubmed.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Julio Mercader, Huw Barton, Jason Gillespie, Jack Harris, Steven Kuhn, Robert Tyler, Christophe Boesch (2007). "4300-year-old Chimpanzee Sites and the Origins of Percussive Stone Technology". PNAS. Feb.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fox, M. (2007-02-22). "Hunting chimps may change view of human evolution". Retrieved 2007-02-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "ISU anthropologist's study is first to report chimps hunting with tools". Iowa State University News Service. 22 February, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Whipps, Heather (12 February, 2007). "Chimps Learned Tool Use Long Ago Without Human Help". LiveScience. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Tool Use". Jane Goodall Institute. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ "Human-like Altruism Shown In Chimpanzees". Science Daily. June 25, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ Bradley, Brenda (1999). "Levels of Selection, Altruism, and Primate Behavior". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 74 (2): 171–194.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Helene Guldberg (March 29, 2001). "The great ape debate". Spiked online. Retrieved 2007-08-12.

- Pickrell, John. (September 24, 2002). Humans, Chimps Not as Closely Related as Thought?. National Geographic.

See also

External links

- Envirovet - Video clip of Ngamba Island Chimpanzee Sanctuary

- The First 100 Chimps in Research in the USA

- Chimpanzee: Wildlife summary from the African Wildlife Foundation

- Chimpanzees Make/Use Spears

- Chimpanzee Cultures Online

- Kanyawara Chimpanzee Blog from Uganda (Harvard Biological Anthropology research)

- Chimp Haven (The National Chimpanzee Sanctuary)

- Chimps as Pets (SaveTheChimps.org)

- Using Pac-Man to test cognitive reasoning in chimps

- Talking With Chimps

- Jane Goodall's Chimpanzee Central

- New Scientist 19 May 2003 - Chimps are human, gene study implies

- Did chimp and human ancestors interbreed?

- Chimp "Stone Age" Finds Are Earliest Nonhuman Ape Tools, Study Says

- Chimpanzee Facial Expression & Vocalizations

- Fox News: Study: Chimps Are More Evolved Than Humans