Nimrod Expedition: Difference between revisions

Ground Zero (talk | contribs) m →Origins: disambiguate |

italics on ship name |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

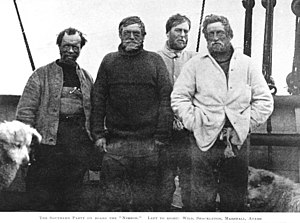

[[Image:TheSouthernParty.jpg|thumb|right|300px|The Nimrod Expedition's South Pole party (left to right): Wild, Shackleton, Marshall and Adams]] |

[[Image:TheSouthernParty.jpg|thumb|right|300px|The Nimrod Expedition's South Pole party (left to right): Wild, Shackleton, Marshall and Adams]] |

||

The '''British Antarctic Expedition 1907–09''', otherwise known as the '''Nimrod Expedition''', was the first of three expeditions to the [[Antarctic]] led by [[Sir Ernest Shackleton]]. It was organized as a private venture, largely reliant on loans and individual contributions, without governmental or institutional support. Its vessel ''Nimrod'' was a 40-year-old wooden sealer of 300 tons (compared with the 1,500 tons of [[Captain Scott]]’s newly-built ship [[RRS Discovery|Discovery]]) and its personnel were generally without relevant experience. Preparations were extremely hurried, a period of only six months elapsing between Shackleton’s first public announcement, on [[12 February]] [[1907]], and the departure of ''Nimrod'' from British waters on [[7 August]] . |

The '''British Antarctic Expedition 1907–09''', otherwise known as the '''Nimrod Expedition''', was the first of three expeditions to the [[Antarctic]] led by [[Sir Ernest Shackleton]]. It was organized as a private venture, largely reliant on loans and individual contributions, without governmental or institutional support. Its vessel ''Nimrod'' was a 40-year-old wooden sealer of 300 tons (compared with the 1,500 tons of [[Captain Scott]]’s newly-built ship [[RRS Discovery|''Discovery'']]) and its personnel were generally without relevant experience. Preparations were extremely hurried, a period of only six months elapsing between Shackleton’s first public announcement, on [[12 February]] [[1907]], and the departure of ''Nimrod'' from British waters on [[7 August]] . |

||

Despite these handicaps, and with a much lower public profile than that of Scott’s expedition six years earlier, the Nimrod Expedition achieved impressive results. The [[South Pole]] was not attained, but the expedition’s southern march reached a [[Farthest South| farthest south]] record latitude at 88°23’S, just 97 nautical miles (112 geographical miles, 188 km) from the Pole. A group led by Dr [[Edgeworth David]] reached the estimated location of the [[South Magnetic Pole]], and the first ascent was made of [[Mount Erebus]], the lofty [[Ross Island]] active volcano. Under Edgeworth David a talented scientific team, which included [[Douglas Mawson]], carried out important geological, zoological and meteorological work. Shackleton’s transport arrangements, based on Manchurian ponies and motor traction as well as sledge dogs, were seen as innovative, and were copied by Scott for his ill-fated [[Terra Nova Expedition]]. |

Despite these handicaps, and with a much lower public profile than that of Scott’s expedition six years earlier, the Nimrod Expedition achieved impressive results. The [[South Pole]] was not attained, but the expedition’s southern march reached a [[Farthest South| farthest south]] record latitude at 88°23’S, just 97 nautical miles (112 geographical miles, 188 km) from the Pole. A group led by Dr [[Edgeworth David]] reached the estimated location of the [[South Magnetic Pole]], and the first ascent was made of [[Mount Erebus]], the lofty [[Ross Island]] active volcano. Under Edgeworth David a talented scientific team, which included [[Douglas Mawson]], carried out important geological, zoological and meteorological work. Shackleton’s transport arrangements, based on Manchurian ponies and motor traction as well as sledge dogs, were seen as innovative, and were copied by Scott for his ill-fated [[Terra Nova Expedition]]. |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

Shackleton as leader favoured a more inclusive and less hierarchical style of leadership than had been evident on Scott’s navy-oriented Discovery Expedition, and this relaxed approach, his natural optimism, and his ability to delegate, helped to keep his party happy and focused. Accepted as, and addressed as, The Boss, his exceptional powers of leadership were, according to his second-in-command [[Jameson Adams]]: "just as much in evidence during the sometimes tiresome and intimate life in the hut as they were on the sledging journey to the Pole".<ref>Riffenburgh, p. 185</ref> |

Shackleton as leader favoured a more inclusive and less hierarchical style of leadership than had been evident on Scott’s navy-oriented Discovery Expedition, and this relaxed approach, his natural optimism, and his ability to delegate, helped to keep his party happy and focused. Accepted as, and addressed as, The Boss, his exceptional powers of leadership were, according to his second-in-command [[Jameson Adams]]: "just as much in evidence during the sometimes tiresome and intimate life in the hut as they were on the sledging journey to the Pole".<ref>Riffenburgh, p. 185</ref> |

||

==Origins== |

==Origins== |

||

Shackleton, as a junior officer on the Discovery Expedition, had been invalided home by Captain Scott in 1903, after a breakdown on the return leg of the southern march to 82°17’S which he, Scott and Edward Wilson had undertaken. Shackleton did not wish to leave the expedition, but Scott’s verdict was that he "ought not to risk further hardships in his present state of health". <ref name = “Preston_58”>Preston, p. 68</ref> In later years [[Albert Armitage]], Scott’s disaffected second-in-command,<ref name = "Crane_239–43">Crane, p. 239</ref> would claim that Scott and Shackleton had seriously fallen out, and that Shackleton’s early departure was a consequence of this. This is contradicted by other evidence, in particular Scott's written report to the Royal Geographical Society which states specifically that the return was ordered solely on account of Shackleton's health and that his future prospects should not suffer.<ref name = "Crane_239‐43">Crane, p. 242</ref>. The pair remained on cordial terms after Scott’s own return the following year.<ref>Shackleton sent Scott a particularly warm letter to welcome him home, informing Scott inter alia that the Royal Scottish Geographical Society had awarded him (Scott) the Livingstone Gold Medal.</ref> |

Shackleton, as a junior officer on the Discovery Expedition, had been invalided home by Captain Scott in 1903, after a breakdown on the return leg of the southern march to 82°17’S which he, Scott and Edward Wilson had undertaken. Shackleton did not wish to leave the expedition, but Scott’s verdict was that he "ought not to risk further hardships in his present state of health". <ref name = “Preston_58”>Preston, p. 68</ref> In later years [[Albert Armitage]], Scott’s disaffected second-in-command,<ref name = "Crane_239–43">Crane, p. 239</ref> would claim that Scott and Shackleton had seriously fallen out, and that Shackleton’s early departure was a consequence of this. This is contradicted by other evidence, in particular Scott's written report to the Royal Geographical Society which states specifically that the return was ordered solely on account of Shackleton's health and that his future prospects should not suffer.<ref name = "Crane_239‐43">Crane, p. 242</ref>. The pair remained on cordial terms after Scott’s own return the following year.<ref>Shackleton sent Scott a particularly warm letter to welcome him home, informing Scott inter alia that the Royal Scottish Geographical Society had awarded him (Scott) the Livingstone Gold Medal.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 03:05, 22 April 2008

The British Antarctic Expedition 1907–09, otherwise known as the Nimrod Expedition, was the first of three expeditions to the Antarctic led by Sir Ernest Shackleton. It was organized as a private venture, largely reliant on loans and individual contributions, without governmental or institutional support. Its vessel Nimrod was a 40-year-old wooden sealer of 300 tons (compared with the 1,500 tons of Captain Scott’s newly-built ship Discovery) and its personnel were generally without relevant experience. Preparations were extremely hurried, a period of only six months elapsing between Shackleton’s first public announcement, on 12 February 1907, and the departure of Nimrod from British waters on 7 August .

Despite these handicaps, and with a much lower public profile than that of Scott’s expedition six years earlier, the Nimrod Expedition achieved impressive results. The South Pole was not attained, but the expedition’s southern march reached a farthest south record latitude at 88°23’S, just 97 nautical miles (112 geographical miles, 188 km) from the Pole. A group led by Dr Edgeworth David reached the estimated location of the South Magnetic Pole, and the first ascent was made of Mount Erebus, the lofty Ross Island active volcano. Under Edgeworth David a talented scientific team, which included Douglas Mawson, carried out important geological, zoological and meteorological work. Shackleton’s transport arrangements, based on Manchurian ponies and motor traction as well as sledge dogs, were seen as innovative, and were copied by Scott for his ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition.

The expedition was a public triumph, and it brought honours—but not riches—to Shackleton. In geographical and exploration circles, however, its successes were less whole-heartedly applauded. The Royal Geographical Society (RGS) had offered only muted support to the expedition, and had not contributed to its costs, its prior commitment in Antarctic matters lying with Captain Scott. In the eyes of some, Shackleton’s triumphs were compromised because he had broken an undertaking given to Scott that he would not base his winter quarters in the McMurdo Sound area, which Scott was claiming as his own "field of work" and reserving for a future, as yet undefined, expedition. This dispute soured relations between the two men, who nevertheless maintained public civilities, but led to a complete fracture of Shackleton’s formerly close relationship with Edward Wilson. The financial chaos which surrounded the enterprise also caused a breach between Shackleton and his principal backer, William Beardmore.

Shackleton as leader favoured a more inclusive and less hierarchical style of leadership than had been evident on Scott’s navy-oriented Discovery Expedition, and this relaxed approach, his natural optimism, and his ability to delegate, helped to keep his party happy and focused. Accepted as, and addressed as, The Boss, his exceptional powers of leadership were, according to his second-in-command Jameson Adams: "just as much in evidence during the sometimes tiresome and intimate life in the hut as they were on the sledging journey to the Pole".[1]

Origins

Shackleton, as a junior officer on the Discovery Expedition, had been invalided home by Captain Scott in 1903, after a breakdown on the return leg of the southern march to 82°17’S which he, Scott and Edward Wilson had undertaken. Shackleton did not wish to leave the expedition, but Scott’s verdict was that he "ought not to risk further hardships in his present state of health". [2] In later years Albert Armitage, Scott’s disaffected second-in-command,[3] would claim that Scott and Shackleton had seriously fallen out, and that Shackleton’s early departure was a consequence of this. This is contradicted by other evidence, in particular Scott's written report to the Royal Geographical Society which states specifically that the return was ordered solely on account of Shackleton's health and that his future prospects should not suffer.[4]. The pair remained on cordial terms after Scott’s own return the following year.[5]

However, Shackleton’s keen disappointment at what he perceived as a personal failure meant that, on his return to England, he was felt the need to redeem himself.[6] It did not necessarily follow that this would be through a resumption of his Antarctic work; this was an option, but not one that he immediately pursued, declining to act as Terra Nova’s chief officer during the second Discovery relief expedition, although helping to fit her out.[7] Thereafter he took actions which could have prevented any swift resumption of his Antarctic career, applying for a regular Royal Navy commission (which was refused),[8] securing the post of Secretary of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society,[9] and standing (unsuccessfully) for Parliament.[10] On 9 April 1904 he got married.[11] He also pursued various business schemes, none of which prospered, and in 1906 was working for the industrial magnate Sir William Beardmore, as a public relations officer. [12]

At what point Shackleton decided definitely to return to the Antarctic is not clear. According to Huntford he was stung into action by the references to his physical breakdown in Scott’s The Voyage of the Discovery, published in 1905.[13] Whatever his motivation, he began drawing up a prospectus and looking for potential backers. His initial plans appear in an unpublished document dated early 1906,[14] and include a financial estimate of £17,000,[14] although at this stage he had no backing whatever. It was not until early 1907 that his employer, William Beardmore, offered a £7,000 loan guarantee.[15] With this in hand, Shackleton felt able to make his intentions clear to the Royal Geographical Society, on 12 February 1907.[16]

Preparations

Organization and finance

Shackleton’s original plan was to base himself at the old Discovery Expedition headquarters in McMurdo Sound, and from there to mount journeys to reach the geographical South Pole and the South Magnetic Pole. There would be other journeys, and continuous scientific work. [14] This early plan also reveals Shackleton’s proposed transport methods: the use of dogs, ponies and a specially designed motor vehicle. Neither ponies nor motor traction had been used in the Antarctic before. Shackleton wrote: "Though I propose taking a motor, I would not rely entirely on this, as, with sixty dogs and a couple of ponies, I am quite certain that the South Pole could be reached".[17]

By the time he made his plans public, in February 1907, a new objective had been added: the exploration of the land to the east of the Great Ice Barrier, known as King Edward VII Land. Increased emphasis was now placed on the scientific programme, which was to "continue the biological, meteorological, geological and magnetic work of the Discovery."[18] Shackleton also revised his cost estimate to a more realistic £30,000.[19] However, the response of the RGS to his plans was at best lukewarm; Shackleton would learn later that the Society was by now aware of Captain Scott’s wish to lead a new expedition, and wished to reserve its full approval for him.[19]

Shackleton intended to arrive in Antarctica in January 1908, which would mean leaving England during the 1907 summer. Within a bare six months it was necessary to acquire a ship, fit it out for Antarctic work, obtain all the equipment and supplies needed for the expedition, recruit the personnel and, above all, to obtain the necessary finance, none of which was yet secured beyond Beardmore’s guarantee. An expedition office was opened at No. 9 Regent Street[20]. To obtain the necessary sledging equipment Shackleton travelled to Norway. While there he attempted to secure a 700–ton polar vessel, the Bjorn, that would have served ideally as an expedition ship, but she was beyond his means. He had to settle for the elderly, much smaller Nimrod, which he was able to acquire for £5,000.[21][22]

Shackleton was shocked by his first sight of Nimrod when she arrived in London from Newfoundland in June 1907. "She was much dilapidated and smelt strongly of seal oil, and an inspection […] showed that she needed caulking and that her masts would have to be renewed."[23] However, in the hands of experienced ship-fitters she soon "assumed a more satisfactory appearance". Later, Shackleton reported, he became extremely proud of the sturdy little ship.[23] However, at this stage his principal concerns were financial. As midsummer approached he had secured little backing beyond Beardmore’s guarantee, and lacked the funds even to complete the refit of the ship.[24] In mid-July Shackleton approached the philanthropic Earl of Iveagh,[25] who agreed to guarantee £2,000 provided that Shackleton found others to bring the amount to £8,000. This he did, including £2,000 from Sir Philip Brocklehurst, who paid this sum to secure a place on the expedition.[24]

A last-minute gift of £4,000 from Shackleton's cousin William Bell[26] still left the expedition far short of the required £30,000, but at least enabled Nimrod to sail, after inspection by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra.[27] A further £5,000 was provided as a gift from the Government of Australia, and the New Zealand Government gave £1,000.[28] By these means and with other smaller loans and donations the £30,000 was raised. But by the end of the expedition its total cost had risen, by Shackleton's estimate, to £45,000.[29] It required a government grant of £20,000 to enable Shackleton to repay his guarantors, and it is likely that some debts were written off.[29]

Personnel

Shackleton hoped that his expedition team would contain a strong element from the Discovery Expedition, to give it a base of experience. He offered his friend Edward Wilson the post of chief scientist and second-in-command, but was refused, ostensibly on the grounds of Wilson’s work with the Board of Agriculture’s Committee on the Investigation of Grouse Disease.[30] Refusals followed in quick succession from former Discovery officers Michael Barne, Reginald Skelton and George Mulock. It was the last of these that inadvertently revealed to Shackleton that the former Discovery hands had all committed themselves to Scott’s as yet unannounced expedition.[31][32] From the Discovery Shackleton was able to secure the services only of the two Petty Officers Frank Wild and Ernest Joyce.

Shackleton’s second-in-command—although this was not announced until the expedition reached the Antarctic—was Jameson Boyd Adams, a Royal Naval Reserve lieutenant who had turned down the chance of a regular commission to join Shackleton.[33] He would also act as the expedition’s meteorologist. Nimrod’s would be captained by another naval reserve officer, Rupert England, with John King Davis, who would later make a great reputation as an Antarctic captain, as chief officer.[34] Former P and O officer Aeneas Mackintosh, who would later be transferred to the shore party, was appointed as Nimrod’s second officer.[35] Also destined for the shore party were the two surgeons, Alistair McKay and Eric Marshall, Bernard Day the motor expert, and Sir Philip Brocklehurst, the subscribing member who had been taken on as assistant geologist.[36]

The scientific team that departed from England was slight; apart from the two doctors it consisted of the 41-year-old biologist John Murray and the 21-year-old geologist Raymond Priestley, a future founder of the Scott Polar Research Institute.[37] However, the team was to be greatly strengthened by two additions made when Nimrod reached Australia. The first of these was Tannatt William Edgeworth David, Professor of Geology at the University of Sydney.[38][39] The second was a former pupil of David’s, Douglas Mawson, now a lecturer in mineralogy at the University of Adelaide. Both men originally expected to sail down and back in Nimrod, but both were persuaded to become full members of the expedition, and both made important contributions to its scientific achievements. David was also influential in securing the Australian Government’s £5,000 grant.[38]

Promise to Scott

Expedition

Voyage south

On January 1, 1908, the Nimrod left Lyttelton, New Zealand. On January 29, [[1 908]], the ship entered McMurdo Sound, but the pack ice blocked their path. After a few days wait the pack ice did not relent. The Nimrod followed the coast of Ross Island northward to Cape Royds, twenty miles from Hut Point. High volcanic hills sheltered the cove from the prevailing winds, several freshwater ponds lay nearby and their meat supply Adelie Penguins nested just beyond a low ridge. Shackleton believed the site to be perfect and the men began unloading supplies at once. During the next three weeks, they erected the prefabricated hut, built a stable for the ponies and hauled tons of provisions over the floes to shore. On February 23, 1908, the Nimrod left to return to New Zealand.

At Cape Royds

During their stay the men wrote, typeset and printed on a small hand press the 120-page Aurora Australis, the first book published in Antarctica.

Accomplishments of the expedition included the first ascent of Mount Erebus, the active volcano of Ross Island; an expedition to the approximate location of the Magnetic South Pole by Douglas Mawson, Edgeworth David and MacKay (16 January 1909); and locating the Beardmore Glacier access to the Antarctic Plateau.

"Furthest South"

On October 29, 1908, at 10:00 hours Ernest Shackleton, Frank Wild, Eric Marshall, Jameson Adams and the ponies Grisi, Socks, Quan and Chinaman, pulling the loaded sledges started on the 1,600 mile round trip to the South Pole. Because of poor success with dogs during Scott's 1901–1904 expedition, Shackleton used Manchurian ponies for transport on the Ice Barrier. They did not prove to be entirely successful.

On January 9, 1909, after facing many hardships including a difficult climb up the Beardmore Glacier, some harsh weather, lack of food and weakness Shackleton accepted the inevitable; they must turn back or die. Shackleton, with Wild, Marshall, and Adams, had reached 88°23'S: a point only 97 nautical miles (180 km) from the South Pole. While the expedition did not make it to the pole, Shackleton, Adams, Marshall, and Wild were the first humans to not only cross the Trans-Antarctic mountain range, but also the first humans to set foot on the South Polar Plateau. It should be pointed out that Shackleton and his group were exceedingly fortunate to return from the Antarctic interior. They had cut rations severely, such that there was no margin of safety. They had very good weather throughout their return, in contrast to Scott's experience three years later. They achieved the "Furthest South" record which would stand until Roald Amundsen reached the Pole in December 1911.

On February 27, 1909, after many hardships on their return journey, Eric Marshall collapsed with severe dysentery. While Jameson Adams remained with Marshall, Frank Wild and Ernest Shackleton continued on to Hut Point, which they reached on February 27, 1909. There, they learned that they had missed the Nimrod by two days. For the rest of the night, they huddled together and discussed their limited options. The next morning they set fire to the small magnetic observation hut, hoping to attract the crew's attention if the Nimrod was close enough to see the flames. The crew did see the burning hut and the ship returned.

Shackleton guided the rescue party to Adams and Marshall and by 4 March 1909, all were safe on board the Nimrod.

Journey to the South Magnetic Pole

Impact

On 23 March 1909, Shackleton cabled London from New Zealand with news of the expeditions results, including the first ascent of Mount Erebus and the first successful trek to the South Magnetic Pole. On 14 December 1909, Ernest Shackleton was knighted.

Postage stamps

Ernest Shackleton had been sworn in as the first postmaster of King Edward VII Land as the Ross Dependency was then known, and the New Zealand Post Office overprinted some 23,492 postage stamps with the name King Edward VII Land for use by the Expedition, see Postage stamps and postal history of the Ross Dependency.

Future

Shackleton had not had his fill of Antarctica. In 1914, he returned with the ill-fated Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition to attempt the first crossing of the continent from the Weddell Sea to Ross Sea.

See also

References

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 185

- ^ Preston, p. 68

- ^ Crane, p. 239

- ^ Crane, p. 242

- ^ Shackleton sent Scott a particularly warm letter to welcome him home, informing Scott inter alia that the Royal Scottish Geographical Society had awarded him (Scott) the Livingstone Gold Medal.

- ^ Fisher, pp. 91–92

- ^ Huntford, pp. 120–21. At the same time Shackleton helped equip the Uruguay, the ship being prepared for the relief of Otto Nordenskjold’s stranded expedition.

- ^ Fisher, pp. 79–80

- ^ Fisher, pp. 83–84

- ^ Fisher, pp. 96–97

- ^ Fisher, p. 89

- ^ Fisher, p. 99

- ^ Huntford, p. 145

- ^ a b c Fisher, pp. 102–03 Cite error: The named reference "Fisher_101–03" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Huntford, p. 156

- ^ Shackleton, p. 2

- ^ Fisher, p. 102

- ^ Shackleton, p. 3

- ^ a b Huntford, p. 158 Cite error: The named reference "Huntford_158–61" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Shackleton, p. 5

- ^ Shackleton, pp. 5–11

- ^ Huntford, p. 175

- ^ a b Shackleton, p. 11

- ^ a b Huntford, p. 178 Cite error: The named reference "Huntford_178–79" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Head of the Guinness brewing family

- ^ Huntford, p. 183

- ^ Shackleton, p. 20

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 140

- ^ a b Huntford, p. 314 Cite error: The named reference "Huntford_314–15" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 109

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 110

- ^ Of those who refused Shackleton, only Wilson actually went with Scott on the Terra Nova Expedition.

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 133

- ^ Riffenburgh, pp. 123–25

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 141

- ^ Shackleton, pp. 17–18

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 134, p. 303

- ^ a b Riffenburgh, pp. 138–40 Cite error: The named reference "Riffenburgh_138–40" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ David actually joined the expedition as a physicist. He was also appointed chief scientific officer.

Further reading

- Shacklteon, E. (1999). The Heart of the Antarctic: Being the Story of the British Antarctic Expedition, 1907-1909. Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-0684-8

- Riffenburgh, B. (2004). Shackleton's Forgotten Expedition : The Voyage of the Nimrod. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 1-58234-488-4

- Shackleton, E.. (1986). Aurora Australis. Paradigm Press. ISBN 0-948285-07-9

External links

- Shackleton hut to be resurrected at the BBC