Siege of Boston

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

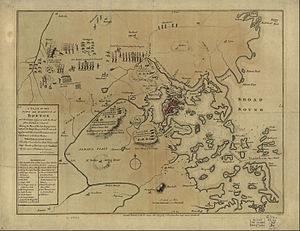

The Siege of Boston (April 19, 1775 – March 17, 1776) was the opening phase of the American Revolutionary War, in which New England militiamen—and then the Continental Army—surrounded the city of Boston, Massachusetts, to prevent movement by the British Army garrisoned within. As a siege it was only partially successful, but it played an important role in the creation of the Continental Army and promoting the unity of the Thirteen Colonies. It also served to shape the attitudes and character of participants on both sides. The most important single event of the siege was the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Background

The Battle of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775 drew thousands of militia forces from throughout New England to the land surrounding Boston. These men remained in the area and their numbers grew. At first, General Artemas Ward, as the head of the Massachusetts militia, was in charge of the siege. He set up his headquarters at Cambridge and positioned his forces at Charlestown Neck, Roxbury, and the Dorchester Heights. Initially, the 6,000 to 8,000 rebels faced some 4,000 British regulars under General Thomas Gage and had them trapped in the city. HAjksjfksjdf GOOgOo GAGA. YAy WAt am i doin. Insert non-formatte == [Headline text] == d text hereSubscript text

Escalation

The British were surrounded on land north, west, and south of Boston, but the harbor side of the city remained open for the Royal Navy under Vice Admiral Samuel Graves to sail in supplies from Nova Scotia, Providence, and other places. Colonial forces could do little to stop these shipments due to the naval supremacy of the British fleet and the complete absence of a Continental Navy in the spring of 1775. Nevertheless, the town and the British forces were on short rations, and prices rose rapidly. Another factor was that the American forces generally had information about what was happening in the city, but General Gage had no effective intelligence of rebel activities.

On May 25, 1775, Gage received about 4,500 reinforcements and three additional Generals: Major Generals William Howe, John Burgoyne, and Henry Clinton. Gage began plans to break out of the city.

On May 27, American forces strengthened the siege during the Battle of Chelsea Creek by removing British supplies of livestock from the islands of Boston Harbor. American fire prevented Royal Marines from landing to recover the animals, and the British schooner Diana was destroyed.

Bunker Hill

On June 15, the Committee of Safety learned of Gage's plans to attack at Dorchester Heights and the Base of the Charlestown Peninsula. They sent word to General Ward to fortify Bunker Hill and the heights; he assigned Colonel William Prescott the Bunker Hill task.

On June 17, as the result of the Battle of Bunker Hill, British forces under General Howe seized the Charlestown peninsula. (The battle was somewhat misnamed since most of the fighting was done at Breed's Hill next to Bunker Hill.) The British did take their objective, only after two failed charges, but did not break out of Boston because the Americans held the ground at the base of the peninsula. With some 1000 men killed or injured the British losses were so heavy that there were no more direct attacks on American forces. From this point, the siege essentially became a stalemate.

Fortification of Dorchester Heights

On July 3, George Washington arrived to take charge of the new Continental Army. Forces and supplies came in from as far away as Maryland. Trenches were built at the Dorchester Neck, and they were extended toward Boston. Washington reoccupied Bunker Hill and Breeds Hill without opposition. However, these activities had little effect on the British occupation.

On November 11, 1775, Washington wrote to Congress of an incident during the siege, in which Col. Woodbridge and part of his 25th Regiment (Massachusetts) joined with Col. Thompson’s regiment, defending against a British landing at Lechmere’s Point, and “gallantly waded through the water, and soon obliged the enemy to embark under cover of a man-of-war…”[1]

Subsequently, in the winter of 1775–76, Henry Knox and his engineers used sledges to retrieve 60 tons of heavy artillery that had been captured at Fort Ticonderoga. Bringing them across the frozen Connecticut River, they arrived back at Cambridge on January 24, 1776. Weeks later, in an amazing feat of deception and mobility, Washington moved artillery and several thousand men overnight to occupy Dorchester Heights, overlooking Boston. Since it was the middle of winter and the continental army was unable to dig into the frozen ground on Dorchester Heights, rather than entrenching themselves, Washington's men used logs, branches and anything else available to fortify the position overnight. General Gage observed that it would have taken his army weeks to build Washington's earth fort. The British fleet ceased to be an asset, because it was anchored in a shallow harbor with limited maneuverability, and the American guns on Dorchester Heights were aimed at the fleet.

Aftermath

The siege was over when the British sent a message to Washington stating that if the British troops were allowed to vacate the city and embark unchallenged, then the British would not destroy the town. Washington agreed and the British set sail for Halifax, Nova Scotia on March 27, 1776. The militia went home, and in April, Washington took most of the Continental Army forces to fortify New York City.

Since 1901, Suffolk County, Massachusetts has celebrated March 17 as a holiday known as Evacuation Day.

References

- Boatner, Mark Mayo, III. Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. New York: McKay, 1966; revised 1974. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

- Frothingham, Jr., Richard: History of the Siege of Boston and of the Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, Second Edition, published by Charles C. Little and James Brown, Boston (1851). This historical book is available online via the Google Books Library Project at http://books.google.com/books?id=xl4sAAAAMAAJ.

Footnotes

- ^ Sparks, Jared: The Writings of George Washington, Vol III, Little, Brown, and Company, Boston (1855) p. 157.