Pennsylvania Canal (Delaware Division)

Delaware Division of the Pennsylvania Canal | |

Delaware Canal State Park in Bristol | |

| Location | Easton, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Built | 1831 |

| MPS | Covered Bridges of the Delaware River Watershed TR (AD) |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001756[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 29, 1974 |

| Designated PHMC | January 1949[2] |

* The Delaware Canal took over the easy part of the journey for the coal barges transiting down the rapids strewn path of the Lehigh Valley from Mauch Chunk and the heights of Nesquehoning, Pennsylvania and the huge coal fields that connected beyond them. Millions of tons of coal would travel from Wilkes-Barre down the Lehigh Valley transportation infrastructure, then finish its journey to the coal yards which distributed coal to housing and industries on the Delaware Canals barges—much of it making the trip down from the Wyoming Valley over the mountains by railroad hopper cars.

* The Delaware and Lehigh Canals also connected from Easton, PA by ferry services across the Delaware River to New Jersey and the Delaware and Raritan Canal, connecting industrial loads to New York City.

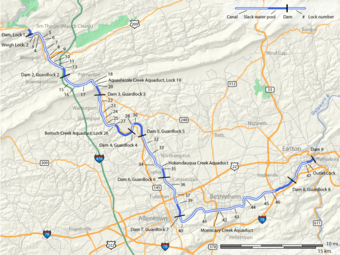

The Delaware Division of the Pennsylvania Canal, more commonly called the Delaware Canal, runs from the Lehigh River at Easton (home of The National Canal Museum and terminal end of the Lehigh Canal) south to Bristol, as part of Pennsylvania's solution to the new nation's (first) energy crises. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania built the Delaware canal to feed anthracite stone coal to energy hungry Philadelphia as part of its transportation infrastructure building plan known as the Main Line of Public Works—an legislative initiative creating a collection of self-reinforcing internal improvements to commercial transportation capabilities.

The Delaware Canal—like the Lehigh Canal—was primarily meant to carry the 'fuel of choice of the day', anthracite coal—and other bulk goods such as gravel and limestone, cement, and lumber—from the northeastern reaches of Pennsylvania to Philadelphia. In reverse flow, the two canals carried manufactured goods, iron products and (a few decades later) steel products to the Northeast cities as well as each connected via their junction to New York City and points in New Jersey. The two Canals reached their peak shipping in 1855, after which coal transport down the Lehigh corridor was taken up increasingly by railroads—but the canals stayed in operation until the Great Depression in the early 1930s.

The Pennsylvania Canal system was spurred by the early success of the Erie Canal in New York State, which had opened in 1825. First opened in 1832 after the original construction failed in 1830 and had to be re-engineered by Josiah White of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company (who'd offered to engineer and build the Delaware Canal for a break in fees in 1824), the Delaware Canal still has most of its original locks, aqueducts, and overflows.[3] According to the National Park Service, it was the "longest-lived canal in the country".[3] The canal runs down a channel dug parallel to the Delaware River from Easton to Bristol, Pennsylvania— where over the years, it carried millions of tons of anthracite from the privately developed Lehigh Canal to distribute it to the city and for export via the port of Philadelphia; the canal's line of travel is generally within sight of the river.

History

The Delaware Canal originally was 60 miles (96.6 km) in length. Width is approximately 60 feet (18.3 m)[4] and depth is approximately 3 feet (0.9 m). Construction, which was done entirely with hand tools using primarily imported labor from Ireland, started in 1829. The state sold the canal to the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company in 1858.

But competition from the railroad led to a decline in barge traffic. By the 1920s, anthracite coal was waning as a source of fuel. The last commercial through traffic traveled the canal in October 1931 and the bankrupt Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company sold the canal back to the state for a nominal fee.

In 1933, a private group called The Delaware Valley Protective Association[5] (DVPA) was founded to protect the canal as a historic asset. The DVPA persuaded the state to resume maintenance of the canal in 1940, when its towpath became Theodore Roosevelt State Park. The berms were restored and the canal was refilled with water.

Through the 1940s and 1950s, the canal was left mostly untouched. In the early 1960s, however, Pennsylvania officials explored plans to pave over the canal and create a road for cars. Local residents fought for the canal's protection. In 1964, Bucks County historian and DVPA member Willis M. Rivinus wrote the first Guide to the Delaware Canal[6] to call attention to the canal's value.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, the DVPA and other influential citizens sought to secure federal landmark status to protect the Canal. In 1974, the Canal was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1976, it was designated a National Historic Landmark,[7] helping to guarantee its preservation. The towpath itself was named an official National Recreation Trail.

In 1988, the U.S. government created the Delaware and Lehigh National Heritage Corridor, covering a 165-mile north-south swath of eastern Pennsylvania that includes the Delaware Canal.[8] In 1989, Theodore Roosevelt State Park was renamed Delaware Canal State Park.

However, public funding for the canal often has been inadequate and, as in other parts of the country, private non-profit groups have been created to fill the void. In 1983, Bucks County resident Betty Orlemann organized the Friends of the Delaware Canal (FODC),[9] now the canal's largest fund-raising and volunteer group. (The DVPA no longer exists). Under long-time executive director Susan Taylor, the FODC also functions as a watchdog group, ensuring goals are to met to make the towpath trail walkable over its entire length and to eventually get the canal fully watered from Easton to Bristol.

Portions of the Delaware Canal towpath were washed away or damaged during successive floods in 2004, 2005 and 2006. A number of sections of the towpath were closed and impassable, including a long stretch north of Washington Crossing and sections south of Riegelsville. In February 2008, a section of the towpath collapsed and 23 miles (37 km) of the canal lost water.[10]

Through funds from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (PA DCNR) currently is refurbishing the washed out sections of the canal.[4] As of October 2009, according to Delaware Canal State Park manager Rick Dalton, 75 percent of the towpath had been restored and was expected to be fully walkable by summer 2010.

Engineering

At New Hope, there was a clever bit of engineering used to pump the water from the Delaware River into the canal using the river's own force. An undershot water wheel was connected to another wheel with buckets, which lifted water up to the canal level.[11]

Alvin Harlow also reports that a few hundred yards above those, there was an outlet lock to the Delaware River, and on the other side was a river lock to the Delaware and Raritan canal. To cross the river, the engineers made a clever arrangement: a cable was put across the river, and to this cable, two wheels were attached, with cables (of unequal length) attached to the boat and the wheels. The effect was that the current of the river would push the boat, as a sail, and the boat being diagonal (from the cables to the wheels being of unequal length), would be pushed across the river.[12]

Mule Barge Tourist Ride

Mule-drawn barges, operated by private concessionaires, provided rides for chartered private parties running from a landing at Lock #11 at New Hope north to a point about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) above Centre Bridge, for a total one-way ride length of 4.5 miles (7.2 km).

Tourist rides were also offered, however, they stopped in the vicinity of the Rabbit Run bridge, which carries PA 32 over the canal, about 1 mile (1.6 km) north of Lock #11. These rides were offered from approximately 1954 to 2006. Each boat could transport between 55 and 80 passengers and were pulled by two mules. Four boats, the Americana (painted red, white & blue), the Independence, the Liberty, and the Spirit of New Hope were used from the inauguration of the tourist ride until the 1997 season, when they were replaced by two new boats, the Molly Pitcher and the Myfanwy Jenkins (pronounced "Mivanway").[citation needed]

Since 1997, operation of the barges have been under regulations by the U.S. Coast Guard (for example, steersmen are required to obtain a Master Mariner's license) and, if reopened, would face regulations imposed in 2009 on its sister operation on the Lehigh Canal in Easton, PA by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security for crew members in "sensitive shipboard and dockside locations".[13]

See also

- Lehigh Canal – A sister canal in the Lehigh Valley that fed coal traffic to the Delaware Canal via a connection in Easton, Pennsylvania.

- Delaware and Raritan Canal – A New Jersey canal connection to the New York market across the Delaware River.

- Chesapeake and Delaware Canal – A canal crossing the Delmarva Peninsula in the states of Delaware and Maryland, connecting the Chesapeake Bay with the Delaware Bay.

Footnotes

References

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ "PHMC Historical Markers". Historical Marker Database. Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ a b "Delaware Canal". Nat'l Park Service. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ a b Coleman, Anthony (March 16, 2009). "Canal work flows along". The Times of Trenton. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:0n14xVmyZ70J:www.dcnr.state.pa.us/stateParks/parks/delawarecanal/landuse/u1lesson10lp.doc+delaware+valley+protective+association&cd=9&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

- ^ Guide to the Delaware Canal, Willis M. Rivinus, photographs by Louis Comfort Tiffany, Route maps by Edith C. Smith, New Hope, PA, 1964, 1967, 1972, 1978, 1984, 1989, 1993, 2004

- ^ http://www.nps.gov/history/nhl/designations/Lists/PA01.pdf

- ^ The Complete Guide to the Delaware and Lehigh National Heritage Corridor, Lehigh River Foundation, Bethlehem, PA, 1994

- ^ http://www.fodc.org

- ^ http://infoaboutdelaware.com/general-news/23-miles-of-delaware-canal-loses-water-in-towpath-collapse-wilkes-barre-times-leader

- ^ Harlow, Alvin F. (1926). Old Towpaths, The Story of The American Canal Era. New York & London: D Appleton & Co. p. 306.

- ^ Old Towpaths, p. 307

- ^ The Morning Call article on requirements by the Transportation Security Administration

External links

- Canals in Pennsylvania

- Canals on the National Register of Historic Places

- Historic American Engineering Record in Pennsylvania

- National Historic Landmarks in Pennsylvania

- Transportation in Northampton County, Pennsylvania

- Transportation in Bucks County, Pennsylvania

- Pennsylvania state historical marker significations

- Canals opened in 1832

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania

- National Register of Historic Places in Bucks County, Pennsylvania