Öræfajökull

| Öræfajökull | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Öræfajökull from Skaftafell |

||

| height | 2110 m | |

| location | Iceland | |

| Coordinates | 64 ° 0 ′ 52 ″ N , 16 ° 40 ′ 30 ″ W | |

|

|

||

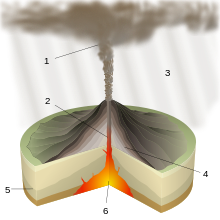

| Type | Stratovolcano , subglacial volcano | |

| rock | predominantly rhyolite | |

| Age of the rock | 700,000 years | |

| Last eruption | 1727 (active) | |

| First ascent | August 11, 1794 by Sveinn Pálsson | |

Öræfajökull ([ ˈœːraivaˌjœːkʏtl̥ ], Icelandic for "desert" or "desert glacier ") is the name of an Icelandic glacier that is part of Vatnajökull and is located in the southeast of Vatnajökull National Park .

Although the name refers to the glacier, it is also used for the volcanic massif below . Its highest peak, Hvannadalshnúkur, is the highest point in Iceland at 2110 m . The area is located in the municipality of Hornafjörður .

Location of the glacial volcano

The volcano under the glacier is located in a not very densely populated area around 100 km west of the city of Höfn and has been part of the Vatnajökull National Park since 2004 .

Name of the glacial volcano

Öræfajökull has erupted twice since the settlement. Many farms were destroyed by the ash and glacier runs. The area around the volcano is therefore also called Öræfi (German desert, wasteland ).

The volcano was previously called Hnappafellsjökull , one also finds the name Knappafell for the mountain, on the other hand mountain peaks at the summit are called Hnappar and a courtyard at its foot is called Hnappavellir .

It was renamed Öræfajökull ( desert glacier ) following eruptions in the 14th century that left the land deserted and almost wiped out the municipality of Litlahérað in particular .

geology

Öræfajökull belongs to the group of stratovolcanoes . The volcanic massif covers 285 km³, making it one of the largest in Iceland. At the summit there is a 5 km wide caldera that is filled with glacial ice.

The caldera is approx. 550 m deep and nine valley glaciers extend from it down to the plains. 14 mountain peaks tower on the edge of this caldera, all over 1500 m high, three of them are among the highest in the country and one of them is the Hvannadalshnúkur.

Volcanic activity

The eruption of 1362

Since the settlement, the volcano has devastated the area in two enormous explosive eruptions. The first, a Plinian eruption , occurred in 1362 and destroyed several thriving communities. 42 farms were destroyed and an entire district, Litlahérað ( small district ), also called Hérað milli sanda ( district between the sand plains ), then fell into desolation.

It was the largest explosive eruption in Iceland in the past 1100 years and the third largest since the end of the Ice Age around 10,000 years ago. The approx. 10 km³ of volcanic loose material and ash formed up to 35 km high eruption columns and were carried by the wind mainly to the north and northwest in such a way that even in the approx. 400 km distant West Fjords, heavy ashfall could be detected. Remarkable amounts of this ash layer can still be seen in the inland desert today. The eruption was associated with both strong glacier runs and pyroclastic flows . Both of these caused the presumably high number of deaths.

Geological studies have shown that the eruption sites were in the summit area. The eruption also marks the most significant eruption of rhyolite tephra in Iceland in historical times, with a magnitude comparable to that of Pinatubo in 1991.

Few sources, including the Skálholt annals , document the catastrophe. There the effects of the strong Tephrafall are reported in particular . The ash and volcanic slag would have z. B. clogged the outflow of rivers and streams until the water broke through the barrier and caused a flood. The ships would also have had difficulty maneuvering in the Westfjords because the loose material was so thick on the water.

According to tradition, the only survivor of this disaster was a shepherd boy who took refuge in a cave above Svínafell . No exact figures are known about the deaths at that time, but a considerable number of the approx. 400 people who lived there were probably killed. This would make this the most devastating eruption in Iceland's history apart from the Lakia eruptions from 1783 to 1784. On the other hand, there are no figures whatsoever about the effects of the Eldgjá volcanic eruptions and many others.

The 1727 eruption

In August 1727 the volcano erupted again, but this time the explosive eruption was nowhere near as strong as that of 1362. A crevice opened further down the mountain, above the Sandfell . However, there were again numerous glacier runs . The water was huge Eisklötze with it that long on the Sander were before wegtauten. Their traces can still be found there today. A detailed description of this eruption is available from the pastor of the local parish, Jón Þorláksson . The series of eruptions lasted until April or May 1728.

21st century

In August 2011, unusually high seismic activity was measured at Öræfajökull for the third time in the last 20 years. In November 2017, a cauldron around 1 km in diameter was found in the glacier as a result of apparently increased geothermal activity, and the preceding months were also characterized by increased seismic activity. As a consequence, the Aviation Color Code was changed from green to yellow.

The glacier

The glacier fills the volcano's 14 km² caldera. From here, some glacier tongues reach down into the valley. The slopes have an average gradient of 14 °.

The outlet glaciers include z. B. Svínafellsjökull (in the west) or the Kvíajökull (in the south), where the highest glacial moraines in Iceland can be found at 100 meters. At the foot of Fjallsjökull (to the east) there is a small glacial lake with icebergs and floes.

In addition, the outlet glaciers of the Öræfajökull glacier cap, which flow to the north, merge with the Vatnajökull plateau glacier, so that both together form a continuous glacier surface.

The glacier had a not to be underestimated influence on geology as a science, more precisely, glaciology , because the (presumably) first climber, the doctor and naturalist Sveinn Pálsson in 1794, when looking at the glacier from above, recognized that glaciers had their flow properties from high have viscous materials and therefore the glacier tongues flow down the mountain, albeit much more slowly than water.

Sediments at Svínafell

At Svínafell you can find sediment deposits from the Ice Age. The layers are about 120 m thick and contain v. a. Plant remains from birch, crowberries, various grass and ferns. A vegetation similar to that found in Iceland today. Basalt layers are located below them , but above them there are u. a. Pillow lavas , which indicates a formation during the Ice Age . In fact, the age of the layers is around half a million years.

Settlement of the area

Although close at Ingólfshöfði with Ingólfur Arnarson came around the year 870, the first settlers on land and then in Reykjavik settled, this area was even settled until much later.

Öræfajökull landmark

The glacier volcano also forms the southeasternmost tip of Iceland. As such, it has always been a landmark for seafarers. In the 20th and 21st centuries, planes flying to Iceland from Europe headed for the mountain.

See also

literature

- Jens Willhardt, Christine Sadler: Iceland . Michael Müller Verlag, Erlangen 2003, ISBN 3-89953-115-9

- Thor Thordarson, Armann Hoskuldsson: Iceland. Classic Geology in Europe 3. Harpenden, 2002, ISBN 1-903544-06-8

- Ari Trausti Guðmundsson : Land in the making. An outline of the geology of Iceland. Reykjavík 1996, ISBN 9979-2-0347-1

Web links

photos

- Painting “Öræfajökull” by Jón Stefánsson in the National Gallery

Scientific contributions

- Öræfajökull in the Global Volcanism Program of the Smithsonian Institution (English)

- On subglacial volcanism using the example of Öræfajökull. (PDF) Springer Link (English)

- Rune S. Selbekk, Reidar G. Trønnes: [ The 1362 AD plinian Öræfajökull eruption, Iceland: Petrology and geochemistery of large-volume homogeneous rhyolitic eruption .] In: Natural History Museum , first published in: Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research , 2010 , 160, pp. 42-58 (English)

- Sebekk et al: The 1364 Öræfajökull eruption, Iceland: Petrology and geochemistry of large-volume homogeonous rhyolite . (PDF) In: Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research , 160, 2007, pp. 42–58 (English); at the outbreak of 1362

- A. Walker et al .: Rhyolite volcanism at Öræfajökull Volcano, Iceland - geochemistry, field relations & 40Ar / 39Ar geochronology , 05/2010, EGU General Assembly 2010, held 2-7 May, 2010 in Vienna, Austria, p. 606, bibcode : 2010EGUGA..12..606W (English)

Other

- Description of eruptions of Öræfukökull (Icelandic)

Sports

Individual evidence

- ↑ HUSchmid: English-Icelandic German. Hamburg (Buske) 2001, p. 312

- ↑ Íslandshandbókin. Náttúra, saga og sérkenni. 2. bindi. Edited by T. Einarsson, H. Magnússon. Reykjavík (Örn og Örlygur) 1989, p. 685

- ↑ Thor Thordarson, Armann Hoskudsson: Iceland. Classic Geology in Europe 3. Harpenden 2002, p. 117

- ↑ cf. also: Íslandshandbókin. Náttúra, saga og sérkenni. 2. bindi. Edited by T. Einarsson, H. Magnússon. Reykjavík (Örn og Örlygur) 1989, p. 685

- ↑ http://icelandicvolcanos.is/?volcano=ORA# Downloaded October 5, 2019; FutureVolc: Catalog of Icelandic Volcanoes. Öræfajökull

- ↑ http://icelandicvolcanos.is/?volcano=ORA# Downloaded October 5, 2019; FutureVolc: Catalog of Icelandic Volcanoes. Öræfajökull

- ↑ Thor Thordarson, Armann Hoskudsson: Iceland. Classic Geology in Europe 3. Harpenden 2002, p. 119

- ↑ a b c wayback.vefsafn.is

- ↑ Unusual seismic activity on Iceland's largest volcano. In: derStandard.at. September 14, 2011, accessed December 11, 2017 .

- ↑ Report Icelandic Meteorolog. Office, November 17, 2017

- ↑ Thor Thordarson, Armann Hoskudsson: Iceland. Classic Geology in Europe 3. Harpenden 2002, p. 117 f.

- ↑ T. Einarsson, H. Magnússon (Eds.): Íslandshandbókin. Náttúra, saga og sérkenni . 2. bindi. Örn og Örlygur, Reykjavík 1989, p. 686

- ↑ Thor Thordarson, Armann Hoskudsson: Iceland. Classic Geology in Europe 3. Harpenden 2002, p. 118 f.