17th Symphony (Haydn)

The Symphony in F major Hoboken directory I: 17 wrote Joseph Haydn to 1760/61. The first set was a symphony that time an unusually long implementation .

General

As with some of the mostly undated early symphonies of Haydn's early symphonies, No. 17 presents the difficulty of classifying it chronologically. In No. 17, the first movement, because of its length, and in particular the development, suggests a later year of composition, while movements 2 and 3 are in the style of Haydn's earliest symphonies. The information on the time this symphony was composed also varies accordingly in the literature. The Eisenstadt Haydn Festival gives 1760/61 as the period of origin.

The symphony is one of the first works by Haydn to be performed in the New World. This is evidenced by a handwritten copy of the work made by the German-American composer Johann Friedrich Peter in 1766 and kept in the Winston-Salem archives in North Carolina.

To the music

Instrumentation: two oboes , two horns , two violins , viola , cello , double bass . At that time, a bassoon was used to reinforce the bass voice, even without separate notation . On the participation of a harpsichord - continuos are competing views in Haydn's symphonies.

Performance time: approx. 15 minutes (depending on compliance with the prescribed repetitions)

With the terms of the sonata form used here, it should be noted that this scheme was designed in the first half of the 19th | century (see there) and can therefore only be transferred to a work composed around 1760 with restrictions. - The description and structure of the sentences given here is to be understood as a suggestion. Depending on the point of view, other delimitations and interpretations are also possible.

First movement: Allegro

F major, 3/4 time, 164 bars

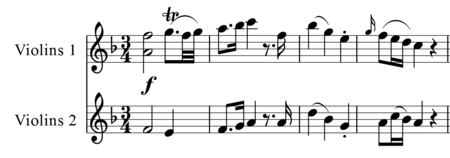

The Allegro with its formative eighth note movement, which runs through large parts, begins forte with the powerful first theme, which is four bars and consists of two motifs: Motif 1 with an emerging gesture and trill, Motif 2 with an upbeat fourth and a closing sixteenth turn . The theme is repeated one octave lower piano.

In the following passage from bar 8, several motifs / figures are lined up: Motif 3 with forte chord strike and rhythmic piano figure (this can be derived from motif 2 by fourth and sixteenth notes), even eighth notes in staccato with syncope accompaniment of the violins, the staggered motif 4 performed between the violins with the sixteenth-note turn from motif 2 and a final octave jump, as well as motif 5 with tone repetition and countervoice-like movement in the 2nd violin. The upbeat line-up of a figure from motif 5 leads in bars 28/29 to a further motif 6 with a double- stroke sixteenth- note figure that cushions the movement and prepares the dominant C major.

In C major, motif 1 now appears twice as a “second theme” in the forte, then only in the violins and piano of motif 6 as a variant in a question-and-answer structure. A phrase-like spinning leads over to the final group, which begins in bar 42 forte with motif 7 sequenced upwards (change from octave phrase in the bass and descending staccato chains on the violins) and ends the exposition fortissimo with tremolo and chord strikes.

The development first brings the first theme in C major, but immediately moves it back to F major. Haydn then processes the motifs of the exposition by varying them and leading them through different keys: starting from motif 3 with a twist to B flat major, he takes up the syncopation passage and the “dialogue motif” 4. In bar 80 a contrasting passage begins with a change of a piano figure and an energetic advancement, whereby the piano figure can be derived from the continuation of the second theme. This is followed by the sequenced motif 7 from the final group as well as motif 5. Haydn effectively prepares the recapitulation by making the music seem to exhale in pianissimo.

The recapitulation begins in bar 113 forte with the first theme. It is structured largely like the exposition, but the syncope passage is missing. Both parts of the sentence (exposition as well as development and recapitulation) are repeated.

The Allegro stands out because of the length of the development in relation to the length of the other parts of the sentence. It is particularly noteworthy that the development is longer than the exposition (exposition: 54 bars, development: 58 bars, recapitulation: 52 bars). This is unique within the early Haydn symphonies, since otherwise the development (or middle section, as there is often no “processing” of the material of the exposition in the narrower sense) is significantly shorter.

Howard Chandler Robbins Landon describes the Allegro as a "curious milestone" in the development of the first movements of the Haydn symphonies. However, Haydn only fills “old wine into new bottles” here: the Allegro represents an elongated two-part movement that on the one hand has outgrown its form, on the other hand it does not yet form a fully developed three-part structure (exposition, development, recapitulation in the sense of the later developing sonata form).

Second movement: Andante, ma non troppo

F minor, 2/4 time, 107 bars

The Andante is only for strings and almost entirely piano. The voice-leading 1st violins begin the eight-bar main theme, which consists of two-bar motifs 1 to 4 (or two four-bar groups). The topic has a "strangely halting" effect, or rather. creates a somewhat march-like character.

The theme is followed by a passage with tone repetition and pendulum movement (motif 5), which merges into motif 6 with its singing melody of the 1st violin, while the 2nd violin continues the pendulum movement. With the closing turn in bar 18, E flat major is reached. In the tonic parallel in A flat major, the head of the opening theme (motif 1) begins again, but then changes to motif 7 with a sweeping gesture and a varied pendulum figure. The section ends in bar 28 with another closing turn. The final group in A flat major is characterized by the parallel violins with their seconds of sighs (motif 8).

In the development, Haydn initially sequenced motif 1 upwards, then he worked out motif 5 in three variants (from measure 47 in staggered use, then after the interposed motif 2 as a combination with motif 7 and a similar closing turn as in measure 28, then after a chromatic passage with voice leading in the lower voices). A syncopated figure with a chromatically falling line leads back to the recapitulation in F minor.

The recapitulation from bar 76 is structured similar to the exposition. Both parts of the sentence (exposition as well as development and recapitulation) are repeated.

Third movement: Allegro molto

F major, 3/8 time, 92 bars

The short movement in the typical “Kehraus” character of the time begins forte with the dance-like, eight-bar main theme in the vocal oboes and violins. It consists of two four-bar halves. The head motif of both halves is characteristic with an opening chord strike, triplet and a rising eighth figure. It is formative for the rest of the sentence. The pause between the two halves in measure 4 is filled by horn, viola and bass.

In bars 9 to 20, Haydn changes to the dominant C major with a trill motif derived from the eighth figure and ascending sixteenth notes. After a contrasting insert with a chromatic variant of the head motif, alternating between piano (violins) and forte (unison), the final section follows, which in turn draws on the head motif of the theme.

The short middle section in C major combines the head motif with the ascending sixteenth notes as a six-bar unit that is repeated piano and in minor. The recapitulation is structured like the exposition, but after the contrasting insert as a continuation of the unison figure, a downward sequencing of a triad figure in the strings follows. The movement ends with a short coda of chord melodies. Both parts of the sentence (exposition as well as middle part and recapitulation) are repeated.

"The conclusion is a lively movement in 3/8 time, one of those harmless, playful, conventional finals that are characteristic of most of these early symphonies by Haydn."

Individual references, comments

- ^ A b c d e Walter Lessing: The Symphonies by Joseph Haydn, in addition: all masses. A series of broadcasts on Südwestfunk Baden-Baden 1987-89, published by Südwestfunk Baden-Baden in 3 volumes. Volume 1, Baden-Baden 1989, pp. 69 to 70.

- ↑ Robbins Landon (1955 p. 175): 1757-1761; Anthony van Hoboken ( Joseph Haydn. Thematic-bibliographical catalog raisonné, Volume I. Schott-Verlag, Mainz 1957, p. 21): “composed around 1764”, Michael Walter ( Haydn's symphonies. A musical work guide. CH Beck-Verlag, Munich 2007 , ISBN 978-3-406-44813-3 , p. 28): "1762?".

- ↑ Information page of the Haydn Festival Eisenstadt, see under web links.

- ↑ Examples: a) James Webster: On the Absence of Keyboard Continuo in Haydn's Symphonies. In: Early Music Volume 18 No. 4, 1990, pp. 599-608); b) Hartmut Haenchen : Haydn, Joseph: Haydn's orchestra and the harpsichord question in the early symphonies. Booklet text for the recordings of the early Haydn symphonies. , online (accessed June 26, 2019), to: H. Haenchen: Early Haydn Symphonies , Berlin Classics, 1988–1990, cassette with 18 symphonies; c) Jamie James: He'd Rather Fight Than Use Keyboard In His Haydn Series . In: New York Times , October 2, 1994 (accessed June 25, 2019; showing various positions by Roy Goodman , Christopher Hogwood , HC Robbins Landon and James Webster). Most orchestras with modern instruments currently (as of 2019) do not use a harpsichord continuo. Recordings with harpsichord continuo exist. a. by: Trevor Pinnock ( Sturm und Drang symphonies , archive, 1989/90); Nikolaus Harnoncourt (No. 6-8, Das Alte Werk, 1990); Sigiswald Kuijken (including Paris and London symphonies ; Virgin, 1988-1995); Roy Goodman (e.g. Nos. 1-25, 70-78; Hyperion, 2002).

- ^ Howard Chandler Robbins Landon: Haydn: Chronicle and works. The early years 1732-1765. Thames and Hudson, London 1980, p. 289.

- ↑ Howard Chandler Robbins Landon (1980 p. 289) highlights this passage as an example of a successful forte piano contrast in the sentence: “But then he drops the dynamic level still more, to pp. It's so simple. It is so magical. When it is over and we sweep into the recapitulation, that previous section sounded absolutely inevitable; that it does so is, simply, the hand of the master. "

- ↑ a b c The repetitions of the parts of the sentence are not kept in some recordings.

- ^ A b Howard Chandler Robbins Landon: The Symphonies of Joseph Haydn. Universal Edition & Rocklife, London 1955, pp. 205 to 206.

- ↑ James Webster: Hob.I: 17th Symphony in F major. Information text of the Haydn Festival Eisenstadt on Symphony No. 17 by Joseph Haydn, see under web links.

- ^ Robbins Landon (1955, p. 205): “A curious milestone in this formal development is represented by Symphony No. 17. "

Web links, notes

- Audio samples and information on Haydn's 17th Symphony from the project “Haydn 100 & 7” at the Haydn Festival in Eisenstadt

- Joseph Haydn: Sinfonia No. 17 F major. Philharmonia Volume No. 717, Vienna 1963. Series: Howard Chandler Robbins Landon (Ed.): Critical edition of all symphonies by Joseph Haydn. (Pocket score)

- Symphony No. 17 by Joseph Haydn : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Sonja Gerlach, Ullrich Scheideler : Symphonies around 1757 - 1760/61. In: Joseph Haydn Institute Cologne (ed.): Joseph Haydn works. Series I, Volume 1. G. Henle-Verlag, Munich 1998, 297 pages.