81st Symphony (Haydn)

The Symphony in G major Hoboken directory I: 81 wrote Joseph Haydn probably in 1784 during his tenure as Kapellmeister to Prince I. Nikolaus Esterházy . The symphony is particularly striking because of the unusual beginning of the first movement.

Composition of the symphonies no.79, 80 and 81

For the origin of the symphonies No. 79 to 81, probably composed in 1784, see Symphony No. 79 .

The work is judged differently in literature except for the unusual beginning of the first movement. According to Michael Walter, "the combination of the uncomplicated, the popular and the artificial" is not convincing, the introductory bars of the first movement could "not keep their promise of an unconventional development of the movement", the andante is a "somewhat lengthy set of variations, whose internal contrasts are too little outlined" are, the minuet conventional and the originality of the final movement is exhausted in its beginning. Charles Rosen, on the other hand, considers the symphony “underrated”, and Antony Hodgson also praises the individual movements (including the trio from the minuet) and describes the final movement as “one of Haydn's best finals”.

To the music

Instrumentation: flute , two oboes , two bassoons , two horns , two violins , viola , cello , double bass . On the participation of a harpsichord - continuos are competing views in Haydn's symphonies.

Performance time: approx. 20 to 25 minutes (depending on the tempo and adherence to the prescribed repetitions).

With the terms of the sonata form used here, it should be noted that this scheme was designed in the first half of the 19th century (see there) and can therefore only be transferred to Symphony No. 81 with restrictions. - The description and structure of the sentences given here is to be understood as a suggestion. Depending on the point of view, other delimitations and interpretations are also possible.

First movement: Vivace

G major, 4/4 bars, 179 bars

The unusual beginning of the movement is emphasized several times in the literature: The opening G major chord strike of the entire orchestra is followed by three "empty" bars that are only filled by the "drum bass" of the cello on G. In measure 3, the seventh f is superimposed on the 2nd violin , i.e. H. A tone that is far from harmony in G major (can be interpreted as belonging to C major).

“The subsequent leads between the 1st and 2nd violin also leave us in the dark as to whether we are in C major or G major. Only from the 7th measure on, when the 1st violin reaches the note 'f sharp', does this peculiar veil lift and in the gently circling eighth note movements of the 1st violin the key of G major finally comes to light. "

This movement, which is somewhat more flowing after the “lead motif” with pause, closes in bar 12 with chord strokes in the dominant D major. Then the “first theme” (can also be interpreted as an introduction depending on your point of view) is repeated, now in the fourth bar of the theme with accompanying viola and at the end of the tonic in G major. In contrast, from bar 24 a forteblock of the whole orchestra follows, in which an "accent motif" (the accent is formed as syncope on the second bar time) with a sixteenth- note roller is characteristic, replaced by a chromatic tremolo passage (again with accents ), and finally a motif with a fourth or third in dotted rhythm and a virtuoso sixteenth run downwards (“running motif”). The running motif appears alternating between upper and lower parts and then changes with the isolated dotted rhythm in energetic unison to the double dominant A major, which dominantly prepares the entry of the second theme in D major.

The second theme in the "tender serenade tone" consists of a simple question-answer structure with an appendix. First strings with bassoon (which replaces the missing string bass) present the theme, then it is repeated as a variant with a recumbent tone in the 1st oboe (but without bassoon) and with chromatic enhancement reminiscent of Mozart , before bassoon and viola the chromatic figure spin away. The final group from bar 61 (forte, whole orchestra, D major) repeats this continuation in the bass over tremolo and then takes up again the dotted rhythm in unison and the sixteenth-note roller from the first theme.

The development (from bar 68) begins forte from D major with the accented motif, then brings the beginning of the first theme as a piano variant and then in a longer forte passage first processes the running motif, then the emphasized dotted rhythm and finally the accented motif.

Just like the beginning of the movement, the fuzzy entry of the recapitulation is also emphasized in the literature: the tone repetition on E in viola and bass from measure 94 and the dissonant B of the second violin (in the interval of the tritone to E instead of the seventh from the beginning of the movement) terminate the subject. The theme appearance has, however, been greatly changed: in the lead motif, the first violin leading the voice omits the prelude, and instead of the second theme part with the more flowing movement, Haydn inserts two inserts. The first insert again consists of “empty” bars with tone repetition of the 2nd violin, the second from a further appearance of the lead motif, which “is processed and remodeled in a very concentrated form and a compact set for six bars.” This is also striking in this case Enter the woodwind. Only then (from bar 110) does the second part of the theme follow, in which the flute now also leads the part while the cello has replaced its tone repeater for a recumbent tone.

From bar 117, the theme is followed by a dramatic twist in G minor with tremolo, then the accented motif, the tremolo passage, which is more extensive and somewhat more dramatic than the exposition, and the second theme. The final group has been changed: the chromatic twist from the end of the second theme is continued, the figure with the dotted rhythm is left out in favor of the running motif (which was previously missing in the recapitulation). Haydn ends the movement with a coda , which takes up the beginning of the movement piano as a variant with the participation of the whole orchestra and closes it pianissimo as a simple cadenza. The exposition, development and recapitulation are repeated.

"The beginning of JOSEPH HAYDN's G major symphony No. 81, although it can be easily 'explained' within the framework of the harmony rules, must have sounded rather strange to the contemporary listener [...]."

“In the underrated Symphony No. 81 [...] the opening bars are designed in such a way that they allow a subtle, blurred return to the tonic in the recapitulation. The beginning is quite mysterious after the first, frank chord, but the recapitulation is even more difficult to grasp [...]. "

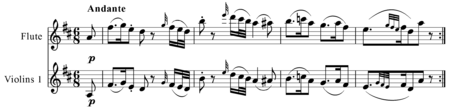

Second movement: Andante

D major, 6/8 time, 60 bars

The Andante is a set of variations with a main theme and four variations.

- The main theme with its characteristic siciliano rhythm is introduced by the flute and first violin, accompanied by the other strings. It is structured in two parts, with each part being repeated (first part four bars, second part eight bars, also with all subsequent variations).

- Variation 1 (bars 13 to 24): D major, figuration of the theme, instrumentation as at the beginning.

- Variation 2 (bars 25 to 40): D minor, whole orchestra involved, contrasting juxtaposition of forte and piano passages. The theme is changed here more than in the other variations. At the end, a dissonant chord emphasized in the forte stands out.

- Variation 3 (bars 41 to 48): D major, strings only, the theme is resolved in triplets in the leading violin.

- Variation 4 (bars 49 to 60): D major, whole orchestra. Theme in original form in flute, 1st violin and partly the oboes. Accompaniment in pizzicato (2nd violin as continuous sixteenth notes).

"It is a peaceful sentence, full of pastoral serenity, which however does not conjure up a specific scene, but rather a fundamental feeling of spaciousness and unlimited landscapes."

Third movement: Menuetto. Allegretto

G major, 3/4 time, 84 bars

The first part of the minuet begins as an eight-bar theme forte, which in the upper parts consists of a staccato tone repeater, a pendulum figure and an upbeat triad motif. The bass accompanies opposing voices in even quarters, hinting at the opening motif and the tone repetition. In contrast, a piano “appendix” of four bars follows, which repeats the top motif as an echo-like variant. The upbeat figure is continued in the second part for eight bars (initially four bars forte in the whole orchestra, then four bars only for strings) before the beginning part returns. This has now been changed and expanded, however, in that the theme head is brought back to D major after its presentation in G major and the piano appendix is replaced by a syncopation passage. Haydn ends the minuet as a coda, in which the solo winds and strings play the opening motif in a question-and-answer dialogue.

In the first part of the trio (also in G major), the solo bassoon and 1st violin play a folk melody, the other strings accompany the G major triad almost unchanged in even quarters. (Depending on your point of view, you can see a relationship to the minuet through hints of the opening motif and the pendulum motif, the ostinato-like accompaniment possibly derived from the beginning of the tone repetition). The second part begins as an eight-cycle spinning of the material, then the first part is taken up. The repetition of the second part is written out, the revision of the first part is now in minor. Some authors interpret this as a “Hungarian” timbre.

Fourth movement: Finale. Allegro, ma non troppo

G major, 2/2 time (alla breve), 141 measures

The periodically structured first theme (main theme) is presented piano by the strings. The voice leading of the continuous eighth note movement is an “original blurring” in the first bar of each half of the theme in viola / bass and goes over to the first violin in the second bar. The theme head with its octave jump up, the tone repetition and the stepped, falling movement is characteristic and important for the further structure of the sentence. In the second half, the theme progresses through a complete cadence (tonic G major, subdominant C major, dominant D major, tonic) in the second half.

The following, fore-pushing and dancing forte block of the whole orchestra is partly reminiscent of the figures of the theme (bar 17 ff.), Contrasting from bar 25, first virtuoso staccato sextoles alternate with the whole orchestra and the 1st violin, then suggestive figures (in the Lombard rhythm ). The five-bar, echo-like phrase repeated in the piano from bar 36 in the dominant D major leads the theme through various voices, and the short final group also uses the theme in the bass, while the other instruments add energetic chord strokes.

The development also begins with the theme in E minor in energetic unison of the whole orchestra, then the music breaks off in a long general pause. Then the main theme begins in the string piano in C major, but is continued differently in the second half of the theme until a long forte block begins. At the beginning he processes the topic with energetic accents, then picks up the sextolen passage and finally emphasizes the topic again over an eleven-bar organ point on D (first in the dialogue of the violins, then with dissonant syncopation in the 1st violin).

The recapitulation (from bar 96) changes in the second half of the main theme throughout the orchestra to forte, the second half of the theme is repeated in various ways. The dance-like passage that follows in the exposition is replaced by a polyphonic treatment of the theme. The rest of the recapitulation from the Sextolenpassage is structured like the exposition. The exposition, development and recapitulation are repeated.

See also

Individual references, comments

- ↑ Information page of the Haydn Festival Eisenstadt, see under web links.

- ↑ a b Michael Walter: Haydn's symphonies. A musical factory guide. CH Beck-Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-44813-3 , p. 84.

- ↑ a b c d Charles Rosen: The classic style. Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven. Bärenreiter-Verlag, 5th edition 2006, Kassel, ISBN 3-7618-1235-3 , pp. 175 to 176.

- ^ A b c Antony Hodgson: The Music of Joseph Haydn. The Symphonies. The Tantivy Press, London 1976, ISBN 0-8386-1684-4 , pp. 107-109.

- ↑ Antony Hodgson (1976), pp. 107-109: “[…] Haydn's high level of inspiration is retained in one of his very finest finales. A dashing movement with a gentle falling beginning […] soon breaks into nervous insistent rhythms over which long-breathed melodies of great beauty are expounded. [...] "

- ↑ Examples: a) James Webster: On the Absence of Keyboard Continuo in Haydn's Symphonies. In: Early Music Volume 18 No. 4, 1990, pp. 599-608); b) Hartmut Haenchen : Haydn, Joseph: Haydn's orchestra and the harpsichord question in the early symphonies. Booklet text for the recordings of the early Haydn symphonies. , online (accessed June 26, 2019), to: H. Haenchen: Early Haydn Symphonies , Berlin Classics, 1988–1990, cassette with 18 symphonies; c) Jamie James: He'd Rather Fight Than Use Keyboard In His Haydn Series . In: New York Times , October 2, 1994 (accessed June 25, 2019; showing various positions by Roy Goodman , Christopher Hogwood , HC Robbins Landon and James Webster). Most orchestras with modern instruments currently (as of 2019) do not use a harpsichord continuo. Recordings with harpsichord continuo exist. a. by: Trevor Pinnock ( Sturm und Drang symphonies , archive, 1989/90); Nikolaus Harnoncourt (No. 6-8, Das Alte Werk, 1990); Sigiswald Kuijken (including Paris and London symphonies ; Virgin, 1988-1995); Roy Goodman (e.g. Nos. 1-25, 70-78; Hyperion, 2002).

- ↑ a b c d e f Wolfgang Marggraf : The Symphonies of Joseph Haydn. The symphonies of the years 1773-1784. Symphony No. 81 in G major. http://www.haydn-sinfonien.de/ , call June 24, 2013.

- ↑ a b c d Walter Lessing: The symphonies of Joseph Haydn, in addition: all masses. A series of broadcasts on Südwestfunk Baden-Baden 1987-89, published by Südwestfunk Baden-Baden in 3 volumes. Volume 2, Baden-Baden 1989, pp. 240 to 241.

- ^ A b c Howard Chandler Robbins Landon: The Symphonies of Joseph Haydn. Universal Edition & Rocklife, London 1955, p. 393.

- ↑ Ludwig Finscher: Joseph Haydn and his time. Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2000, ISBN 3-921518-94-6 , p. 319.

- ↑ Michael Walter (2007 p. 84) speaks of “twelve introductory bars”, only from bar 24 onwards there is “a kind of topic formation”; similar to Ludwig Finscher (2000, p. 319), who speaks of a “piano introduction” that represents a “harmoniously exciting cadenza”.

- ^ A b Klaus Schweizer, Arnold Werner-Jensen: Reclams concert guide orchestral music. 16th edition. Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart, ISBN 3-15-010434-3 , p. 144.

- ↑ a b The repetitions of the parts of the sentence are not kept in some recordings.

- ↑ Hob.I: 81 Symphony in G major. Information text on Symphony No. 81 by Joseph Haydn of the Haydn Festival Eisenstadt, see under web links.

- ↑ "It is a peaceful movement, full of pastoral serenity, yet no scenes are specifically conjured up, rather a general feeling of great space and unlimited landscapes." (Antony Hodgson (1976: 107 to 109.)

- ↑ Antony Hodgson (1976 p. 241) also on the written repetition with a minor ending: "A shiver of exitement must have run through the first audiences at such a great stroke of originality."

Web links, notes

- Recordings and information on Haydn's 81st Symphony from the “Haydn 100 & 7” project of the Eisenstadt Haydn Festival

- Joseph Haydn: Sinfonia No. 81 in G major. Philharmonia No. 881, Universal Edition, Vienna 1965. Series: Howard Chandler Robbins Landon (Ed.): Critical edition of all symphonies (pocket score)

- Symphony No. 81 by Joseph Haydn : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Sonja Gerlach, Sterling E. Murray: Symphonies 1782–1784. In: Joseph Haydn Institute Cologne (ed.): Joseph Haydn works. Series I, Volume 11. G. Henle-Verlag, Munich 2003, 300 pp.