A portrait of the artist as a young man

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (Engl. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man ) is the title of an autobiographical embossed Bildungsroman the Irish writer James Joyce on the life of a young artist from childhood to the study. The main theme is his confrontation with Catholic socialization with the result of leaving Ireland.

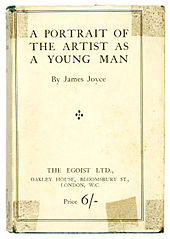

The novel was published in 1914/1915 in sequels in the magazine "The Egoist" and on December 29, 1916 for the first time in book form. The first German translation by Georg Goyert was published in 1926.

overview

The story of Stephen Dedalus takes place at the end of the 19th century. in Ireland . The five chapters are based on the phases of his development: his childhood in Bray with socialization in the family and in "Clongowes College" (Kp 1). His youth after the family moved to Dublin in the Jesuit "Belveder College" (Kp. 2). The adolescent's attempts at self-discovery and the adolescent's difficulties with his or her sexuality in contradiction to the dogmatics of the Jesuit school (Chapter 3). His return to the teaching of the Catholic Church (Chapter 4). The decision against entering the Jesuit order and training as a priest (cp. 4). The discussions with fellow students at the “University College” about the domestic political situation, the demands for self-government and the role of the church as the dominant moral authority in the country. Finding your own way as a writer. He comes to the realization that traditional social conceptions prevent him from freely developing his life and art, and so at the end of the novel he decides to leave his homeland. At his farewell to Stephen sees the successor of Daedalus - myth to which the quote from Ovid's Metamorphoses points: Daedalus invented wings to escape from Minos captivity on the island of Crete (Kp. 5).

plot

- Motto from Ovid's "Metamorphoses"

Chapter 1

The short introductory section ("Once upon a time") exposes his parents, father's uncle Charles, the beloved neighbor's daughter Eileen Vance and the educator Mrs. Riordan (Dante) in the house in Bray and from Stephen's perspective and in his child's language indicates both the loving (dance song) and the fear-inducing educational method: "the eagles come and peck out his eyes" (I, 1). Then the action jumps to Clongowes Wood College, a Jesuit-run boarding school, and shows Stephen staying out of the turmoil of a rugby game. The intellectually gifted but not very athletic boy is on the edge of his elementary class, is mocked into a swamp ditch and ends up with brother Michael in the infirmary because of his poor health, where he hopes to be picked up by his mother (I, 2), but that doesn't happen until the Christmas holidays.

The parents have invited guests to the Christmas dinner (I, 3). A discussion quickly developed around the table about the social, political and religious tensions in Ireland. The occasion is the death of the politician Charles Stewart Parnell in 1891. Mr. Casey is a supporter of Parnell and defends him against the attack by Catholic activists. Uncle and Mrs. Riordan (Dante) take the opposite position. Simon Dedalus supports Casey, his wife tries to balance things out and dampen the emotions. Stephen tries to write a poem about Parnell.

Back in college, discovery of five upper-class students engaging in sexual games and their expulsion from school creates insecurity (I, 4). In response, the school is taking a harder line. Discipline is tightened and students are punished more physically. As Stephens glasses broken by the collision with a cyclist, the study prefect Father Dolan suspects a trick to avoid having to study and punished him with "paw giving" , d. H. with cane blows on the hands. The classmates advise Stephen not to put up with this and to fight back. Stephen overcomes his fear and complains to the principal, Father Conmee. He is mild and assures him that there will be no such repetition. The students celebrate Stephen and he feels triumphant.

Chapter 2

For financial reasons, the parents take Stephen from "Clongowes College" (II, 1). They also have to sell their house in Blackrock, where they now live, and move to Dublin. Stephen falls in love with Ellen at a children's party in Harold's Cross, she shows interest in a friendship, but he is too shy to go into it and transforms her in his poems in Byron's manner, which he translates into his green poetry booklet with the Jesuit motto " Ad maiorem Dei gloriam ”writes about the ideal Mary-like figure“ EC ”accompanying him in his dreams. Through his relationships with Father Conmee, Simon Dedalus has got free places for Stephen and his younger brother Maurice at the“ Belvedere College ”in Dublin and hopes that his children because of the Jesuit school, which is respected in society, they have better opportunities for advancement than with the ordinary "Christian Brothers" (II, 2).

In the third section, the action jumps by two years. Stephen is now around 13 years old and appears at the school's Whitsun game as an “educator”. His classmates tease him with a presumed secret love affair with a beautiful girl. But everything is of a platonic nature and, like EC before, he sings about it in a poem. He has become more self-confident in discussions with his comrades, knows his way around the books of “rebellious writers” better than they do, writes good essays and plays the theater. In the area of tension between adapting to the rules of the Jesuit college and his own head world, he gets into a conflict when teacher Tate interprets his unconscious or conscious critical thoughts as heresy. In a quick reaction, he immediately changes the phrase “without a way to get closer to the Creator” to “without ever reaching him”. That is accepted. But his envious comrades, v. a. Heron, accuse him of this as adaptation and betrayal; on the other hand, when he demonstrates his superiority in literature to them, they criticize his role model Byron as immoral and heretic (II, 3).

The impoverishment of the family leads to financial bottlenecks, which Stephen does not realize in his claims at first. Because his father, whom he accompanied to the auction of his grandfather's property in Cork (II, 4), plays for him the still strong man in his memory of his youth in the city. Stephen lavishly consumed the support money with friends along with an essay prize he won. He suppresses his mother's accusations behind fantasy plans until the money is spent. Now he wanders lonely through the city to the brothel district, driven by the physical tension and the extravagant thoughts expressed in expressive language and ecstatic transgressions about the connection between sinful and holy women (EC). The feeling of breaking the rules increases the pleasure, but this is followed by a fall into solitude: "A cold, light indifference reigns in his soul" when he goes to a prostitute. (II, 5)

Chapter 3

The third chapter describes the mental-physical existential crisis. The 16-year-old dealt intensively with this situation in his school in December during the four-day retreat (III, 1). For three days Stephen heard Father Arnall's sermons, reproduced in detail, on the reflection on the last things, death and judgment as well as the punishments of hell (III, 2). For example, a moment of rebellious pride of the spirit that led to Lucifer's fall from glory, but also venial sins such as an unchaste thought, a lie, angry looks, and wanton indolence, the righteous God who feels insulted and ridiculed cannot let go with impunity. For each of these unconfessed sins the same punishment follows, because the infinite love of the Father God has been rejected, the warnings of the priests have not been listened to and the wrongdoings have not been repented before them. In hell the sinner must irrevocably endure the torment of hell with unimaginable torments in the eternal dark fire. It is mental pains with infinite extent, infinite intensity. The never-ending variety of torture is accompanied by the unbearable cries of other sinners and the constant insults of the devils. At night the images of hell follow Stephen, he becomes aware of his sins and is afraid of the condemnation threatened in the sermons (III, 3). Restlessly he roams the nocturnal streets with his torment of conscience and after an eight-month break he decides to go to confession again. In a chapel that happened to be on his way, he confessed to the priest the long list of his wrongdoings, the whole "dirty river of vice", promised improvement and received absolution. At the closing mass of the retreat on Saturday morning, he felt free from sin and at the beginning of a new life.

Chapter 4

In the fourth chapter, Stephen's efforts to purify himself physically and spiritually through asceticism are told (IV, 1): He arranges his daily routine according to strict rules, often prays the rosary, goes to mass, confesses, reads books of inspiration, disciplines his thoughts to avoid the dangers of mental exaltation and kills his senses: he controls his eyes, smell, taste and feeling. He treats his attacks of anger with humility training. But in living together with others he constantly fears failure and this leads to a feeling of "spiritual dryness", doubts and scruples: "His soul went through a period of desolation." The more he controls himself, the more often he is exposed to temptations. But he knows that a single small transgression would ruin all his efforts, and by resisting he thinks he has improved his life.

Stephen's efforts have been noticed by the teachers and the director asks him if he wants to join the order (IV, 2). He would then be one of the chosen ones who “know about obscure things that were hidden from others.” He himself has also toyed with this idea. His life would be safe and secure, and that would be entirely in the interests of his parents. But his "troubled communication with himself [would] be extinguished by the image of a joyless mask [...] the frostiness and order of this life repelled him". He wonders what would become “of the pride of his spirit”, “which had always made him understand himself as a being that could not be fitted into any order [...] He was destined to experience his own wisdom, or wisdom, far from others to experience others for oneself as a wanderer in the ropes of the world. The cords of the world were their ways of sin. He would fall [...] Not to fall was too heavy [...] He felt the silent fall of his soul ”. He leaves college and returns to his family. His parents have to move out of their home again for financial reasons. But he feels that the clutter, mismanagement, and disorder in his father's house is what "should win in his soul".

Stephen has made a decision: Instead of training for priests, he will attend lectures at the university on English and French literature and physics (IV, 3). During a hike on Dollymount Strand he feels the new freedom: "A day of piebald sea-borne clouds" He feels the symmetry and balance of this sentence and has the vision of receiving a call to rise to flight like the mythical figure Daedalus: In the flight ecstasy swung "his soul [...] high in an air beyond the world and the body [...] was purified in one breath and [...] mixed with the element of the spirit". Stephen wades into the [...] water and sees a girl, alone and quietly looking out to sea: "Her image had penetrated his soul [...] love, err, fall, triumph, life recreated from life! A wild angel had appeared to him [...] to tear open the gates to all the roads of error and glory before him in a moment of ecstasy. On and on and on and on! "

Chapter 5

Stephen's new phase of life initiates a search hike. On his city tours he collects impressions, which he translates into language images in an associative manner. He attends lectures at the “University College” on English and French literature and physics, but not regularly, so that his dissatisfied father calls him “lazy pig”. Like the Jesuit college before, he now experiences the university as a theoretical, dry apparatus. He takes a look back when he meets the Jesuit dean (V, 1), who differs in his modesty from the intellect and rhetorical skills of Father Arnall. Before the start of the lecture, he demonstrates the art of lighting a fire to him in the lecture hall and makes cautious, clever remarks in conversation with him. But in accepting his subordinate role, Stephen recognizes the limitations of his life and thinking. For his fellow students, Stephen is an independent mind and mocker. Some, Temple and Moynihan, are impressed. They discuss both ideological issues, religion or communism, as well as current political issues: MacCann is soliciting signatures in support of a world peace conference proposed by Tsar Nicholas II. Stephen disapproves of the tsar's iconic image similar to Jesus and therefore does not sign the petition. Davin, a down-to-earth farmer's son, is a supporter of Irish nationalism and tries to persuade Stephen to learn Irish. For Stephen, however, nationalism, like language and religion, is a web that prevents him from flying. He wants to go his own way and only follows the arguments of his fellow students from the edge, while his thoughts are filled with art. On the way through the city from the university to the library, Lynch developed his Thomas Aquinas- oriented aesthetic (V, 1): "There are three essentials to beauty, wholeness, harmony and charisma". A central motif of his poetry since his childhood love for Eileen and Ellen has been the platonic lover EC, whom he believes to see again and again in girls he meets. This time, a student who hardly pays him any attention is the inspiration for the connection between the ideal virgin and the seductive beloved, an angel-demon figure from whom he separates again in a feeling of sin. In search of the right rhythm he reworks a Villanelle (V, 2): “Aren't you tired of the glowing questions, The Lure of the Fallen Seraphim?” Stephen discusses his situation with his friend Cranly and explains why he is leaving the country becomes (V, 3). Cranly tries to keep him with the advice that he should not choose the lonely path, but simply adapt to the form according to the society and religious ceremonies, as most do, then his mother would also be satisfied. But Stephen decides differently: “I am not afraid of being alone, or of being cast out for someone else's sake, or of leaving everything that I must leave. And I'm not afraid of making a mistake, even a […] lifelong mistake, and perhaps one that will last as long as eternity Stephen Dedalus under the heading “Away! Away! ”On his mythological role model Daedalus:“ We are of your gender. And in the air they rave about their kind, as they call me [...] and get ready to go and shake their wings, the wings of their jubilant and terrible youth. "

Biographical background

The life stations, locations and dates as well as v. a. the subject corresponds to the biography of the author.

| → biography (selection) |

|

Re. 1:

Re. 2-4:

Re. 5:

|

shape

“A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” is an educational novel in which the entire inner development of the protagonist can be followed from childhood to student days. Individual chapters can be assigned to the school novel , the boarding school novel and the university novel.

While Joyce, in the preliminary study of the novel with the title “Stephen Hero”, written in 1904–1905, still had the story of Stephen and other characters traditionally developed by an authorial narrator , in the “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” everything concentrates on the main character. In personal form , the events are presented chronologically, as is typical for a biography, from his perspective and, in addition, in places in the form of a stream of consciousness , i.e. H. the reader follows the action along with Stephen's thoughts in the language of the respective age group. This is the first time Joyce has used this technique. In terms of content, this means that the “portrait” can be seen as the first part of Stephen Dedalus 'plot and stylistically as a preparation for Ulysses' main work .

reception

Joyce's first novel is considered to be one of the most literary and best of the entire 20th century. In 1998 the “Modern Library” placed him in third place of the “100 best novels of the 20th century in English”. The following Joyce novel "Ulysses" took first place.

German language translations

- The first German translation by Georg Goyert appeared in 1926 under the title Jugendbildnis.

- The new translation by Klaus Reichert under the title A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was first published in 1973 as a separate edition in the Suhrkamp library and in 1987, together with Stephen the Held, was included as volume 2 in the Frankfurt edition of Joyce's works.

- The current translation by Friedhelm Rathjen , published in 2012, is based on the text-critical Garland edition from 1993 edited by Hans Walter Gabler.

See also

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ A portrait of Europe as an old friend, by James Joyce | Daniel Mulhall. December 28, 2016, accessed December 28, 2021 .

- ↑ VIII, 188 on Daedalus' invention of the wings

- ↑ In the study "Stephen Hero" the girl Emma Clery is called: David Sullivan: "Answering Joyce's Portrait". No. 3 "Mishearing Misogny". Papers of Joyce 1. University of California at Irvine 1995. www.siff.us.es ›2013/11› Sullivan.

- ↑ 1898, a year before the Hague Peace Conference

- ↑ The evidence can be found in the references to the Wikipedia article "James Joyce", inter alia. Richard Ellmann: "James Joyce". Oxford University Press, 1959, 1982. ISBN 0-19-503103-2 .

- ^ Paul O'Hanrahan, Dún Laoghaire: "James Joyce and Bray". In: The Irish Times. Feb. 26, 2018. www.irishtimes.com ›letters› jam ...

- ↑ the surviving part of the manuscript was published in 1944.

- ↑ https://www.modernlibrary.com/top-100/100-best-novels/

- ↑ James Joyce: Youth Portrait. German by Georg Goyert. Khein-Verlag, Basel 1926, DNB 574151761 .

- ↑ James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Translated by Klaus Reichert (= Library Suhrkamp. Vol. 350). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1973, ISBN 3-518-01350-5 .

- ↑ James Joyce: Stephen the Hero. A portrait of the artist as a young man. Translated by Klaus Reichert (= James Joyce: Werkausgabe. Volume 2. Edition Suhrkamp. 1435). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1973, ISBN 3-518-11435-2 .

- ↑ James Joyce A portrait of the artist as a young man , German by Friedhelm Rathjen . Manesse, Zurich 2012, ISBN 978-3-7175-2222-5 .