Aisha bint Abi Bakr

Aischa bint Abi Bakr ( Arabic عائشة بنت أَبي بكر, DMG ʿĀʾiša bint Abī Bakr ) (* 613 or 614; † 678 in Medina ) was the third and youngest of the ten wives of the Islamic prophet Mohammed . She was the daughter of the businessman and later caliph Abu Bakr and his wife Umm Ruman. Like Mohammed, Abu Bakr came from the Quraish tribe that was predominant at the time . In Islamic scriptures, her name is often added with the addition "mother of the believers" ( Arabic أمّ المؤمنين, DMG umm al-muʾminīn ) mentioned. She has become known as Muhammad's favorite wife.

The lore about their life

Marriage to Mohammed

In Islamic literature is Aisha's age at marriage majority with six or seven years, the consummation of the marriage records of nine or ten years. The historian Muhammad ibn Saʿd († 845 in Baghdad ) passed down Aisha’s own statement in his class register , which is said to have said:

“The Messenger of God married me in the month of Shawwal in the tenth year of prophecy, three years before the emigration , when I was six years old. The Messenger of God emigrated and arrived in Medina on Monday the 12th Rabīʿ al-awwal , and arranged the wedding with me in the month of Shavwal, eight months after his departure. He married me when I was nine years old. "

In this context, Asma Afsaruddin draws attention to the fact that, according to the information in the biographical lexicon, Ibn Challikāns Aisha was nine years old at the time of marriage and twelve years old when the marriage was consummated. This account is also supported by a report in Ibn Saʿd's class register . She also notes that child marriages were not uncommon in the age of Muhammad. In particular, the marriage between Mohammed and Aisha represented a (political) alliance with Aisha’s father Abu Bakr.

Denise Spellberg points to the importance of her early age at marriage and her thus undisputed virginity as one of several attributes that she emphasizes in the (Sunni) Islamic historiography in her position as the wife of the Prophet compared to his remaining wives and thus also the position of her father as first caliph attached (see also: Schia # The Successor Dispute ): “All these precise references to the age of the bride underpin Aisha's pre-pubescent condition [at the time of marriage] and thus implicitly her virginity. They also explain the differing ages in the historical records. "

The "Defamation Report"

The so-called "defamation report" ( Chabar al-ifk or Hadīth al-ifk ) occupies a large space in the Arabic tradition about Aisha . Accordingly, Aisha was accused of fornication , but exonerated by a revelation ( Sura 24 : 11-20). The report is available in a large number of different versions.

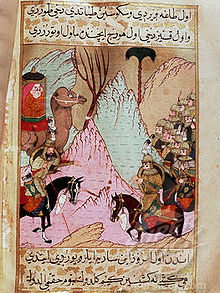

According to the version of Ibn Ishāq , in which Aisha herself appears as the reporter, the starting point of the scandal is Mohammed's campaign against the Banū l-Mustaliq, which took place in January 627 and during which Aisha accompanied him in a camel litter. When the army is about to set off again early in the morning after a night stop near Medina, Aisha leaves to satisfy her need. In doing so, she loses her necklace. The search for it stops them. When she finally found them, the army has already left. The porters charged their camel litter without realizing that it was empty. Aischa is discovered by the allegedly impotent, later martyr Safwān ibn al-Muʿattal (the veil was not a requirement at that time) and saved. He loads them onto his camel and guides them home, leading the camel himself. Upon arriving in Medina, she is slandered for fornication. Since Aisha falls ill after arrival, she learns nothing of the campaign against her, only she is amazed at the indifference of Mohammed towards her. Even in her parents' house, which she moves to after a few days, she does not find out about it. Only more than twenty days later is she informed about the scandal by a woman during a nightly abortion. It becomes clear that Abdallāh ibn Ubayy, the leader of the Banu Khazradsch , and Aisha's relative, Mistah ibn Uthātha, were behind the smear campaign , among others . Mohammed comments on the accusations in a speech and consults with Ali and Usāma ibn Zaid about his further course of action. After making inquiries about her from Aisha’s servant Barīra, he goes to see the weeping Aisha, who is still with her parents. When asked to repent, she protests her innocence. The Qur'anic word in Sura 24: 11-20 is revealed, in which Aisha's innocence is confirmed. The Prophet then holds another chutba in which he recites the revealed verses and orders corporal punishment for the slanderer.

Aisha's jealousy

Modern Arabic works dealing with Aisha emphasize above all her jealousy of the other wives of Muhammad. This picture of Aisha’s jealousy ties in with various anecdotes from the Sīra that also address this aspect. For example, Ibn Ishāq cites an anecdote that Aisha suffered from a severe headache shortly before Muhammad's death. Mohammed, who also had a headache, then said to her: "What harm would it do if you died before me and I then wrapped you in a shroud, said the funeral prayer over you and buried you?" To which Aisha replied: "Bei God, I feel as if I see you in front of me, how you return to my room after my funeral and celebrate the wedding there with one of your wives. "

Political activity after Muhammad's death

During the caliphates of her father and his successor, Aisha had largely stayed out of politics. It was only the growing rebellion against the third caliph that she sympathized, and she supported the rebels. However, since she was also against a caliphate led by Ali , she used the assassination of Uthman as a means against Ali's rule. Together with Talha ibn Ubaidallah and Abdallah ibn az-Zubair , two former companions of Mohammed, she advocated a revolt against the fourth caliph Ali, a cousin of her deceased husband, in 656. The caliph, however, put down the uprising in the so-called " camel battle " near Basra and took Aisha prisoner among others. He later pardoned her and had her escorted to Medina, where she lived until her death in 678. She is said to have decided shortly before her death to be buried next to the other women of Muhammad.

Aisha as a trader

In the hadith literature, Aisha also appears as an important transmitter of religious knowledge. More than 1,200 hadiths are traced back to them. Many accounts describe how Aisha refuted claims by other people about alleged religious prohibitions or commandments by using a behavior of the Prophet as a counter-argument.

literature

- Nabia Abbott : Aishah, the beloved of Mohammed . Chicago 1942, reprint New York 1973.

- Hoda Elsadda: Discourses on Women's Biographies and Cultural Identity. Twentieth-Century Representations of the Life of 'A'isha Bint Abi Bakr. In: Feminist Studies. Volume 27, 2001, pp. 37-64.

- Aisha Geissinger: The exegetical traditions of ʿĀʾisha. Notes on their impact and significance. In: Journal of Quranic Studies. Volume 6, 2004, pp. 1-20.

- DA Spellberg: Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past. The Legacy of 'A'isha bint Abi Bakr. New York 1994.

- W. Montgomery Watt: Art: ʿĀʾi sh a bint Abī Bakr. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition . Vol. I., pp. 307b-308b.

- Asma Afsaruddin: ʿĀʾisha bt. Abī Bakr . In: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson (eds.): Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online, 2016.

Individual evidence

- ↑ The year of birth results from the Islamic sources, which state the year 9 before the hijra . See: AJ Wensinck, JH Kramers (Hrsg.): Concise Dictionary of Islam. Brill, Leiden 1941, p. 29.

- ^ James E. Lindsay: Daily life in the medieval Islamic world. Greenwood Publishing Group 2005, ISBN 0-313-32270-8 , p. 68.

- ↑ Quran 33: 6. Retrieved May 17, 2019 .

- ^ Carl Brockelmann : History of the Islamic Peoples and States. Georg Olms Verlag , 1947, pp. 38, 58, 61, 373.

- ^ Ria Kloppenborg, Wouter J. Hanegraaff: Female stereotypes in religious traditions. EJ Brill, Leiden / New York / Berlin 1995, ISBN 978-90-04-10290-3 , p. 89.

- ↑ Asma Afsaruddin: ʿĀʾisha bt. Abī Bakr . In: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson (eds.): Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online, 2016. See Denise Spellberg: Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past. The Legacy of ʿAʾisha bint Abi Bakr . Columbia University Press, 1994. p. 40

- ↑ Jonathan AC Brown notes with reference to aṭ-Ṭabarīs historical work that Aisha's marriage was consummated only at the time of sexual maturity. See Jonathan AC Brown: Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet's Legacy . Oneworld Publications, 2014. p. 143 and p. 316, note 50

- ↑ See also the traditions of the canonical collections of hadiths on the age of marriage in Buchārī , Book 62, No. 64, No. 65 ( Memento of March 17, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) and No. 88 ( Memento of March 17, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) ( English), and Muslim , Book 8, No. 3309–3311 ( Memento of March 17, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- ↑ See Asma Afsaruddin: ʿĀʾisha bt. Abī Bakr . In: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson (eds.): Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online, 2016 and references there. See also Denise Spellberg: Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past. The Legacy of ʿAʾisha bint Abi Bakr . Columbia University Press, 1994, p. 204, note 54.

- ↑ William Montgomery Watt: 'Ā'isha Bint Abi Bakr. . In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Cf. Nabia Abbott: Aishah - The Beloved of Mohammed . Al Saqi Books, 1985, p. 9 f.

- ↑ See Denise Spellberg: Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past. The Legacy of ʿAʾisha bint Abi Bakr . Columbia University Press, 1994, pp. 27-60, here in particular p. 30 f. and p. 39 f.

- ^ Denise Spellberg: Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past. The Legacy of ʿAʾisha bint Abi Bakr . Columbia University Press, 1994, p. 40. Original: “ All of these specific references to the bride's age reinforce ʿAʾishas pre-menarcheal status and, implicitly, her virginity. They also suggest the variability of Aʾisha's age in the historical record. ”

- ↑ Cf. Gregor Schoeler : Character and authenticity of the Muslim tradition about the life of Muhammad. Berlin 1996, pp. 119-171.

- ↑ Hans Jansen : Mohammed. A biography. (2005/2007) Translated from the Dutch by Marlene Müller-Haas. CH Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56858-9 , p. 326.

- ↑ See Schoeler 124-126. The Arabic text can be viewed here: http://archive.org/stream/p2daslebenmuhamm01ibnhuoft#page/296/mode/2up

- ↑ See Elsadda: Discourses. 2001, pp. 48 and 52.

- ↑ Ibn Hishām: Kitāb Sīrat Rasūl Allāh. From d. Hs. On Berlin, Leipzig, Gotha a. Leyden ed. by Ferdinand Wüstenfeld. 2 vols. Göttingen 1858-1859. P. 1000, lines 15ff. Digitized . See the translation by Gernot Rotter in Ibn Ishāq: The life of the Prophet . Goldmann, Stuttgart 1982, p. 247.

- ↑ Eberhard Serauky : History of Islam. Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-326-00557-1 , p. 146f.

- ↑ See Watt 308a.

- ↑ See Doris Decker: Women as bearers of religious knowledge. Conceptions of images of women in early Islamic traditions up to the 9th century. Stuttgart 2013, p. 235.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Aisha bint Abi Bakr |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | عائشة بنت أَبي بكر (Arabic); Aischa (short form) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Favorite wife of the Prophet Mohammed and daughter of the later Caliph Abu Bakr |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 7th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | 678 |

| Place of death | Medina |