Alamosaurus

| Alamosaurus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

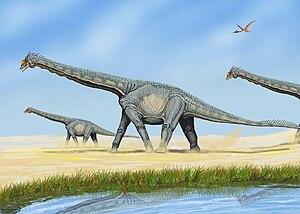

Live artistic representation of Alamosaurus |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Upper Cretaceous ( Maastrichtian ) | ||||||||||||

| 72 to 66 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Alamosaurus | ||||||||||||

| Gilmore , 1922 | ||||||||||||

| Art | ||||||||||||

|

Alamosaurus is a genus of sauropod dinosaur from the late Upper Cretaceous North America. Fossils of this dinosaur come from the US states of New Mexico , Texas , Wyoming and Utah and are dated to the Maastrichtian (about 72 to 66 million years ago).

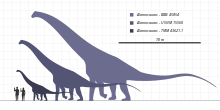

Alamosaurus is one of the better known and most popular Titanosauria and is - in addition to numerous isolated bones - known for several fragmentary skeletons. This genus is considered to be the only sauropod that lived in what is now North America during the late Upper Cretaceous . It was a medium-sized sauropod about 21 meters in length, although new findings indicate a significantly larger body size. The only species is Alamosaurus sanjuanensis .

description

Like all sauropods, Alamosaurus was a four-legged herbivore with a long neck and tail. It was a medium-sized Titanosauria with an estimated length of about 21 meters. The weight was estimated at around 30 tons. However, a study that is still in preparation describes significantly larger bones that suggest one of the largest sauropods at all: A huge cervical vertebra was about as large as the corresponding vertebrae of the gigantic Titanosauria Futalognkosaurus and Puertasaurus .

With about 13 cervical vertebrae, the neck was longer than some related Titanosauria such as Saltasaurus . The spine probably consisted of 10 vertebrae while the sacrum had 6 vertebrae. The tail is fossilized with 30 vertebrae. Skull bones were not found - however, teeth of thin and pin-like shape are known. Although various Alamosaurus finds have been described, there is no evidence of skin bone plates (osteoderms), as found in some other Titanosauria such as Saltasaurus . It is believed that Alamosaurus actually had no osteoderms, and that these skin bones formed several times independently of one another during the evolution of the Titanosauria.

Alamosaurus can be distinguished from other genera by various unique features ( autapomorphies ): Hemal arches are missing from the ninth caudal vertebra, while the breastbone (sternum) shows a sharp craniolateral extension.

Finds and naming

Alamosaurus fossils come from numerous sites in the southwestern United States. A large part of these finds, however, consists only of isolated elements of the limbs and has not been adequately scientifically described. Sullivan and Lucas (2000) note that Alamosaurus is a kind of "trash can genus" ( form genus ) to which numerous sauropod fossils from the Upper Cretaceous North America are tentatively assigned, although many of these assignments may not be justified.

The first scientific description was in 1922 by Charles W. Gilmore . The holotype consists of a shoulder blade (scapula), ischia (ischia) and sacral vertebrae , which come from the Ojo-Alamo formation (or Kirtland formation ) of New Mexico . Later, in 1946, Gilmore described a more complete skeleton from the North Horn Formation of Utah , which consists of a full tail, right foreleg, sternum, and ischium. Other finds have been reported from the Javelina Formation , the El Picacho Formation, and the Black Peaks Formation of Texas . In 2002 the fragmentary skeleton of a young animal from the Black Peaks Formation was described.

Alamosaurus ( Spanish alamo - " poplar ", Greek sauros - "lizard") is named after a geological formation , the Ojo-Alamo formation - not, as is often assumed, after the well-known Fort Alamo in Texas. The found layer is now assigned to the Kirtland Formation. The second part of the species name, sanjuanensis , is named after San Juan County in New Mexico.

Systematics

Alamosaurus is a derived (advanced) representative of the Titanosauria . Most phylogenetic analyzes come to the conclusion that Alamosaurus was closely related to the Mongolian genus Opisthocoelicaudia . Both genera are sometimes summarized as Opisthocoelicaudiinae and compared to another group, the Saltasaurinae . Other researchers classify both genera as outgroups of the Saltasaurinae, considering the Opisthocoelicaudiinae as paraphyletic . The Saltasauridae as well as Alamosaurus and Opisthocoelicaudia are also summarized as Saltasauridae . In contrast to most other previous analyzes, Curry Rogers (2005) comes to the conclusion that Alamosaurus and Opisthocoelicaudia were only distantly related to the Saltasaurinae. Upchurch and colleagues (2004) consider Alamosaurus, however, as a sister taxon of Pellegrinisaurus and thus only as a distant relative of Opisthocoelicaudia .

Two cladogram examples follow - with monophyletic Opisthocoelicaudiinae (Wilson 2002, left) and with paraphyletic Opisthocoelicaudiinae (Calvo and Gonzáles-Riga 2003, right):

|

|

Age and paleobiogeography

Alamosaurus is considered to be one of the last dinosaurs. Its fossils have long been dated exclusively to the late Maastrichtian , the last section of the Cretaceous period immediately below the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary . Because Alamosaurus fossils are relatively common, they were used as marker fossils. Their presence was taken as proof that the present shift belongs to the late Maastrichtian.

However, in recent years it has been recognized that various formations with Alamosaurus fossils are actually older; for example, the Javelina Formation has been re-dated to about 69 million years (late early Maastrichtian). The oldest find comes from the Kirtland Formation of New Mexico and is dated to an age of 72 million years (early Maastrichtian ).

From the Cenomanian , i.e. at the beginning of the Upper Cretaceous, sauropod fossils disappeared from the fossil record of North America and only reappear in the early Maastrichtian with the oldest Alamosaurus fossils. This gap is interpreted by various researchers to the effect that sauropods died out in the early Upper Cretaceous in North America and only immigrated again in the Campanian, probably from Asia or South America.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Dougal Dixon : The World Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs & Prehistoric Creatures. Lorenz Books, London 2008, ISBN 978-0-7548-1730-7 , p. 337.

- ↑ a b c Gregory S. Paul : The Princeton Field Guide To Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ et al. 2010, ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9 , pp. 209-210, online .

- ^ A b c Robert M. Sullivan, Spencer G. Lucas: Alamosaurus (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Late Campanian of New Mexico and its significance. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 20, No. 2, 2000, pp. 400-403, doi : 10.1671 / 0272-4634 (2000) 020 [0400: ADSFTL] 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ↑ Thomas R. Holtz Jr .: Supplementary Information. to: Thomas R. Holtz Jr .: Dinosaurs. The most complete, up-to-date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of all ages. Random House, New York NY 2007, ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7 , online (PDF; 184.08 kB) .

- ↑ a b c d e Thomas M. Lehman, Alan B. Coulson: A juvenile specimen of the sauropod dinosaur Alamosaurus sanjuanensis from the Upper Cretaceous of Big Bend National Park, Texas. In: Journal of Paleontology. Vol. 76, No. 1, 2002, ISSN 0022-3360 , pp. 156-172, doi : 10.1666 / 0022-3360 (2002) 076 <0156: AJSOTS> 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ↑ a b Denver W. Fowler, Robert M. Sullivan: The first giant titanosaurian sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of North America. In: Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. Vol. 56, No. 4, 2011, ISSN 0567-7920 , pp. 685-690, doi : 10.4202 / app.2010.0105 .

- ↑ Michael D. D'Emic, Jeffrey A. Wilson, Sankar Chatterjee : The titanosaur (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) osteoderm record: review and first definitive specimen from India. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 29, No. 1, 2009, pp. 165-177, doi : 10.1671 / 039.029.0131 .

- ↑ a b c d Paul Upchurch , Paul M. Barrett , Peter Dodson : Sauropoda. In: David B. Weishampel , Peter Dodson, Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 259-324.

- ^ A b Charles W. Gilmore : A new sauropod dinosaur from the Ojo Alamo Formation of New Mexico (= Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. Vol. 72, No. 14 = Publication 2663, ISSN 0096-8749 ). Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 1922, digitized .

- ↑ Ben Creisler: Dinosauria Translation and Pronunciation Guide. Archived from the original on November 6, 2011 ; accessed on August 27, 2014 .

- ↑ Jeffrey A. Wilson: An Overview of Titanosaur Evolution and Phylogeny. In: Fidel Torcida Fernández-Baldor, Pedro Huerta Hurtado (eds.): Actas de las III Jornadas Internacionales sobre Paleontología de Dinosaurios y Su Entorno. = Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium about Paleontology of Dinosaurs and their Environment Paleontología de dinosaurios y su entorno. Salas de los Infantes (Burgos, España), 16 al 18 de septiembre de 2004. Colectivo arqueológico-paleontológico de Salas, Salas de los Infantes (Burgos, España) 2006, ISBN 84-8181-227-7 , pp. 169-190 .

- ↑ Kristina Curry Rogers: Titanosauria: A Phylogenetic Overview. In: Kristina Curry A. Rogers, Jeffrey A. Wilson (Eds.): The Sauropods. Evolution and Paleobiology. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2005, ISBN 0-520-24623-3 , pp. 50-103, doi : 10.1525 / california / 9780520246232.003.0003 .

- ↑ Jeffrey A. Wilson: Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistic analysis. In: Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. Vol. 136, No. 2, 2002, ISSN 0024-4082 , pp. 215-275, doi : 10.1046 / j.1096-3642.2002.00029.x .

- ↑ Jorge O. Calvo , Bernardo J. González Riga: Rinconsaurus caudamirus gen. Et sp nov., A new titanosaurid (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina. In: Revista Geológica de Chile. Vol. 30, No. 2, 2003, ISSN 0716-0208 , pp. 333-353, doi : 10.4067 / S0716-02082003000200011 .