Anastasius Wall

| Anastasius Wall | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | a) Long wall , b) Αναστάσειο Τείχος , c) Anastasius Suru , d) Μακρά Τείχη της Θράκης , e) Uzun Duvar |

| limes | Thrace |

| Dating (occupancy) | 5th to 7th century AD |

| Type | Barrier walls from late antiquity with towers, small forts and moats |

| unit | Eastern Roman Army |

| size | Length: 56 km, width approx.3.30 m, height 4 m |

| Construction | Stone construction |

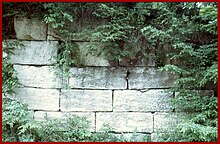

| State of preservation | Wall in the north sector still largely visible above ground. |

| place | Evcik İskelesi / Silivri |

| Geographical location | 41 ° 26 '50 " N , 28 ° 22' 43" E |

| Subsequently | Theodosian wall |

The Anastasius Wall or Long Wall is a barrier wall named after the Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasios I (491-518) to protect the capital Constantinople . It stretched from the Marmara Sea to the Black Sea .

The barrier wall is one of the largest defensive structures of Roman antiquity in Europe and its dimensions are comparable to Hadrian's Wall . A little less than half of its structure has been preserved from it to this day. It is still in relatively good condition, especially in the densely forested regions of the northern sector. Sometimes it reaches a height of up to four meters there. Hardly any remains of the southern sector can be seen today. In addition to the wall itself, ditches, gates and fortresses have been preserved. In the ancient sources it is called “Long Wall” ( Greek : ta makra teiche ) or “Long Wall of Anastasios” (Greek: to makron teichos to legomenon Anastasiakon ).

In modern times, road construction work threatened the facility again and again. From 1994 to 2000 the Anastasius Wall was extensively researched as part of a British research project under the direction of James Crow ( University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne ).

location

The wall is located about 65 kilometers west of today's Istanbul and sealed off the peninsula, at the eastern tip of which the city is located. It runs in a north-south direction from the village of Evcik İskelesi on the Black Sea to the Marama Sea, on the coast of which it ends about six kilometers west of Silivri .

function

According to Johannes Malalas, the wall served to protect the capital and the province of Europe from invasions by the Huns , Avars , Slavs and Proto-Bulgarians from the west, but not - as has long been mistakenly assumed - also the main aqueduct of Constantinople. The aqueducts run too far to the west for the wall to offer effective protection. The Anastasius Wall was designed as a defensive line of defense for the eastern Roman capital and the cities of Rhegion and Selymbria ( Silivri ) to the west of it . It also stood for a new defense strategy for the Eastern Roman Empire, because the days of offensive forward defense were over and the Limes on the Danube border no longer offered any protection. Ostrom only had the choice to curl up, defensive and preservation of the remaining provinces now had top priority. By Edward Gibbon , the boundary walls were also named "last frontier".

Dating

In the Chronicon Paschale ( Easter chronicle ) of 629 - which is not very reliable in this context - the year 507 is given as the foundation date of the wall. Presumably, however, the first barriers were built around 469 or 478, during the reigns of Emperors Leo I (457–474) and Zenon (476–491). Between 490 and 500 the Proto- Bulgarians invaded Thrace repeatedly . After 502, these raids subsided. Anastasius probably had the barrier wall completely expanded during these years and later reinforced. In the relevant sources, he is mentioned several times as the actual client of this building.

In the vita of the pillar saint Daniel from the time of Emperor Leo I and in a fragment of the history of the historian Malchos from the late 5th century, there is also talk of a long wall. In antiquity, however, several such structures existed much earlier, such as the famous barrier walls of the port facilities of Athens in Piraeus and Phaleron . The Gallipoli peninsula was already in the late 6th century BC. BC under Miltiades the Elder , a barrier wall to the interior protected, the so-called Chersonese Wall. On the northern section of the city wall of the port city of Salmydessos , archaeological evidence of a connection between the city fortifications and the Chersonese Wall and the Anastasius Wall was found. Presumably the mentions in Daniel's Vita and in Malchos refer to this building. Constantinople was attacked and besieged several times in the 5th century, but the walls in front are not mentioned in the contemporary sources. The situation is different around 500, when the wall of Anastasius repeatedly plays a major role in the descriptions of the chroniclers. Archaeological investigations have clearly shown that this wall dates from the time of Anastasios. Since the emperor, according to a statement in the “Secret History” of Prokopius of Caesarea, left a state treasure of 320,000 pounds of gold on his death, he was extremely moderate in building the defense system.

development

The construction of the wall was not the only measure Anastasios took to protect the north-west flank of the empire. In this way, the emperor tried to protect the core areas of Eastern Stream. He dissolved the Diocese of Thrace and placed the area between the Wall and Constantinople under two vicarii , civil servants who were subordinate to the Praefectus praetorio Orientis . A magister militum praesentalis , the highest military commander in the empire, was responsible for military matters. The distribution of supervision over the two vicarii could not prove itself in the long run, as Justinian established the office of praetor Iustinianus in Thracia in 535 , restored the diocese of Thracia and had the region administered as the new province of Europe . In addition, some forts and cities on the Black Sea coast ( Scythia ) and the lower Danube were rebuilt or reinforced, which the contemporary historian Prokopios mentions in his work “The Buildings”. Such military construction measures were partly initiated under Anastasios.

Due to its extraordinary length, according to Prokopios, it was very difficult to man the Anastasius Wall sufficiently. That is why he praises Emperor Justinian in his work for strengthening the guards. The proto-Bulgarians and Kutrigurs managed 540 and 558/559 but to overcome them without great effort, since the kingdom suffered from a chronic shortage of trained soldiers and had done well the earthquake of 557 serious damage. In spite of the seemingly great hurry in erecting it, the construction can certainly achieve the quality standard customary for late antique fortifications, as the inside made of regular blocks shows. In 558 it was thanks to the strategic skill of the general Belisarius that the emperor was spared a catastrophic defeat. Justinian then went personally to Selymbria to supervise the rebuilding of the Long Walls himself. This is an indication that this was of great importance to him, since otherwise the emperor rarely left his capital. From 577 to 619 attacks by the Avars and Slavs on the wall were repelled repeatedly. In the year 626, however, it was overrun by the Avars, since almost the entire Eastern Roman army under Emperor Herakleios was on a campaign against the Persians. The Avars then besieged Constantinople, but they could ultimately be repulsed using all available forces.

Even if the Anastasius Wall is mentioned again and again in the sources and apparently was also maintained, it does not seem to have played a major role in the defense of the capital in later times. In the 7th century it was finally abandoned because it had proven to be ineffective overall and, due to the increasingly scarce resources of the empire, no guards and no more funds for maintenance could be raised. The wall was used as a quarry by the surrounding population over the centuries, which accelerated its decline considerably.

Overall system

The approximately 3.30 m wide and five meters high wall extended over a length of around 56 kilometers after its completion. According to Prokopios , it took two days to get from one end to the other. On top of it there was a continuous battlement, which was equipped with battlements on both sides as parapets. A trench was dug in front of the wall on the enemy side as an obstacle to the approach.

In addition, it was reinforced with numerous towers of different sizes, which were used for observation and signaling purposes. As with the older Constantinople city walls , these were either rectangular or pentagonal in plan, and, like there, the wall itself was apparently constructed from regularly laid-up layers of brick and stone. The somewhat larger, pentagonal towers stood in particularly exposed places or at points where the course of the wall changed direction; between them were the slightly smaller, square towers. In the village of Cilingir Tepe the distance between them is only about 45 m, in Dervis Kapi about half of the total length, however, already 120-160 m. In the south, which is easily accessible through the Via Egnatia , they were closer together than in the north. Presumably, the only way to get to the battlements of the wall was through stairs in the towers. The main passage north of the Dervis Kapi was secured by small fortresses (Turkish bedesten = stone construction), namely by a smaller one (Kücük Bedesten) and a larger one (Büyük Bedesten) with defensive trenches; Another hexagonal tower was found near this fortress. The small fort stood at a distance of 3.5 km from each other and housed the guards. In the central sector of the wall there was also a 250 × 300 m large fort ( Kastron ). North of Büyük Bedesten on the hill of Kuskaya Tepe (378 m) is the highest point of the wall, from where, in good weather, the view extends to the coast of the Black Sea in the north and the Marmara Sea in the south. How many soldiers were posted to guard the wall is unknown. Larger troop units were probably only relocated to the wall in the event of a crisis. This is indicated by an episode in October 610 when Emperor Phocas commissioned one of his commanders to defend the wall against the advance of his rival Herakleios .

In the northern section of the Anastasius Wall, considerable remains can still be seen today with a height of around four meters along a road that leads from Karacaköy to the Black Sea, where the wall ends on a hill near the village of Evcik Iskalesi. The very regularly built inside of the wall consists of layers of blocks that protrude from the thick bushes; inside the two-shell wall there is a mixture of mortared rubble stones. In this area not only small gates but also towers can be made out, a square example of which stood on the hill of Hisar Tepe just before the actual wall at the coast.

Remarks

- ↑ a b Meier 2009, p. 142.

- ↑ Malalas, 421 S., pp. 86-87 Thurn; Ivanov / von Bülow 2008, pp. 74-76.

- ↑ Meier 2009, p. 146.

- ↑ Meier 2009, p. 143.

- ↑ a b Ivanov / von Bülow 2008, p. 76.

- ↑ Croke 1982, pp. 62–68, “Since the wall across the Chersonese was known in the fifth an sixth centurie as the Long Wall and since the references to a Long Wall in Malchus and the Life of Daniel cannot be shown to exclude this wall on grounds of topography or context, there is the strong lkehood that the wall refered to in both is actually that across the Chersonese. "

- ↑ Meier 2009, p. 145.

- ↑ Meier 2009, p. 147.

- ↑ See also Crow 1995, p. 117.

- ↑ Meier 2009, p. 143

literature

- Carl Schuchhardt : The Anastasius wall at Constantinople and the Dobrudcha walls . In: Yearbook of the Imperial German Archaeological Institute 16, 1901, pp. 107–127.

- Brian Croke: The Date of the "Anastasian Long Wall" in Thrace . In: Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 20, 1982, pp. 59-78.

- James Crow : The Long Walls of Thrace . In: Cyril Mango et al. (Ed.): Constantinople and its Hinterland: Papers from the Twenty-seventh Spring Symposium on Byzantine Studies, Oxford, April 1993 . Variorum, Aldershot 1995, ISBN 0-86078-487-8 , pp. 109-124.

- James Crow, Alessandra Ricci: Investigating the Hinterland of Constantinople: Interim Report on the Anastasian Long Wall . In: Journal of Roman Archeology 10, 1997, pp. 253-288.

- James Crow: The Anastasian Wall: The Final Frontier. In: Gerhild Klose, Annete Nünnerich-Asmus (ed.): Frontiers of the Roman Empire. Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 978-3-8053-3429-7 , pp. 181-187.

- James Crow: The Anastasian Wall and the Lower Danube Frontier Before Justinian , in: Lyudmil Vagalinski (Ed.): The Lower Danube in Antiquity. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, National Institute of Archeology and Museum, Sofia 2007, pp. 397-410.

- Rumen Ivanov, Gerda von Bülow : Thracia. A Roman province on the Balkan Peninsula (= Zabern's illustrated books on archeology / Orbis Provinciarum ). Zabern, Mainz 2008, ISBN 978-3-8053-2974-3 , pp. 74-76.

- Mischa Meier : Anastasios I. The emergence of the Byzantine Empire , Klett-Cotta Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-608-94377-1 , pp. 141–148.