Aster Ganno

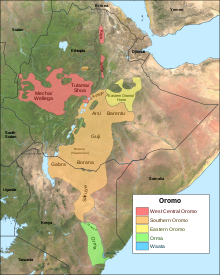

Aster Ganno , actually Aster Gannoo Salbaan (* around 1874 in Illubabor ; † 1962 in Nekemte , Wollega , Ethiopia) was an Ethiopian Oromo and Bible translator . She also created an extensive dictionary of the Afaan Oromoo language . Based on her knowledge of the oral tradition, she wrote down a collection of around 500 songs, fables and stories. Aster Ganno remained unmarried and died of old age.

youth

Aster Ganno's year of birth is generally given as 1874; According to recent research, however, it was the year 1859.

Born in freedom, she was abducted by the king of Limmu-Ennarea's slave hunters . She was the victim of retaliation because the Oromo refused to build a new residence for the King of Limma. Arab slave traders bought the 10 year old girl (or the 25 year old young woman) to transport her to Yemen . The slave ship was intercepted by a warship of the Italian Navy. So the slaves on board were released.

At the beginning of May 1885 the missionary Onesimos Nesib met a group of Oromo, former slaves, on the way to the Munkullo mission school. In the Gäläb refugee camp in northern Eritrea , they formed an Oromo-speaking group that dealt with literature. Nesib accompanied them and entered the school of Munkullo near the city of Massawa as a teacher so that he could teach the Oromo in his mother tongue. He noticed Aster Ganno because she had a special talent for language and literature. Nesib made sure that Emelie Lundahl gave her own Bible for Christmas 1887. That should motivate them to continue reading.

The Oromo Dictionary

Nesib, who had already published religious small letters in Oromo ( afaan Oromoo ), began translating the Bible in 1886. Because he was kidnapped and sold as a slave when he was about four years old, he had not been able to acquire a thorough knowledge of his mother tongue. Work stalled. Aster Ganno had meanwhile finished her school education. Now she was commissioned to work out a Swedish-Oromo dictionary. To do this, she should list the derived vocabulary for each root and identify loanwords from other languages and dialect forms. Nesib did not translate from the basic Hebrew and Greek texts, but he did claim to write pure, idiomatic Oromo. That is why Aster Ganno proofread his translation of the Bible again before having it printed.

Aster Ganno's dictionary manuscript contains approximately 13,000 entries and is now in the Uppsala University Library. Fride Hylander described her job as follows:

“The Galla girl Aster's contribution to dictionary work is very good. She fills a lot of the gaps: she finds the words, and she knows the Galla language better than anyone. It's nice to see how earnest and hard she works all day. ... With pencil in hand, she finds all the words that can be derived from the same root. ... the expression on your face shows intelligence and energy. She seems so learned and skillful that I had great respect for her from the start and was ashamed of my poor language skills. "

Aster Ganno's work was the basis for Nesib's translation of the New Testament ( Kakuu Haaraa ), which was printed in Munkollo in 1893. Nesib then turned to the translation of the Old Testament, again depending on Ganno's preparatory work. In June 1897 the Old Testament was ready in the Oromo language and was printed in St. Chrischona . The whole Oromo Bible was printed under the title Macafa Qulqulluu in St. Chrischona in 1899 and gained recognition from European historians and linguists. Gustav Arén judged: "The Oromo version of the Holy Scriptures is a remarkable achievement, the fruit in every respect of the devotional work of a single man: Onesimos Nesib."

Other works

Aster Ganno wrote down a collection of five hundred songs, fables and stories from her memory, some of which appeared in print in a reader of the Oromo language. The manuscript is now privately owned by the Hylander family. The reader, printed in 1894, has the English title: The Galla Spelling Book and the Oromo title: Jalqaba Barsisa . While the English version only mentions Onesimos Nesib as the author, Oromo Nesib and Ganno are listed together as authors.

On behalf of the Swedish Evangelical Mission, Aster Ganno translated Doctor Barth's Bible Stories into Oromo. In doing so, she only tied the content of her template and told the biblical stories freely in lively, fluent language. This book was printed by St. Chrischona in 1899.

Educational work

Together with Onesimos Nesib, Aster Ganno ran a school in Najo. In 1905, 78 students were taught here in afaan Oromoo .

When their work in Najo met with increasing opposition, Nesib and his team, including Aster Ganno, moved to Nekemte.

With her colleague Feben Hirphee, Aster Ganno regularly visited the women of the Oromo upper class to teach them about housekeeping and child care and to teach them the alphabet. Febeen Hirphee, who came from Jiren in Jimma, was a prisoner of war as a teenager in 1881/82. She was sold as a slave but was ransomed and taught by Swedish Eritrean missionaries.

Appreciation

In the Mekane Yesus Church , Aster Ganno is seen today as an important person in its own church history. Aster Ganno also has a role model function for the participation of women in today's church: “She was an educator, evangelist, linguist; she was gender-sensitive because she paid special attention to the upbringing of women and girls. "

Web links

- Dictionary of African Christian Biography: Nesib, Onesimus

literature

- Mekuria Bulcha: Onesimos Nasib's Pioneering Contributions to Oromo Writing . In: Nordic Journal of African Studies 4/1 (1995), pp. 36–59 ( PDF )

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Senai W. Andemariam: Who should take the Credit for the Bible Translation Works carried out in Eritrea? In: Aethiopica . tape 16 , 2013, p. 108 (Referees the research of: KJ Lundström, Ezra Gebremedhin: Kenisha: The Roots and Development of the Evangelical Church of Eritrea (1866–1935), 2011.).

- ↑ a b c d Kebede Hordofa Janko: Missionaries, enslaved Oromo and their contribution to the development of the Oromo language: an overview . In: Verena Böll (Ed.): Ethiopia and the Missions: Historical and Anthropological Insights . LIT Verlag, Münster 2005, p. 67 (The Oromo ethnic group is often referred to as Galla in older literature, which has a pejorative sound.).

- ↑ Kebede Hordofa Janko: Missionaries, enslaved Oromo . 2005, p. 68 (Other sources give her year of death, without location, as 1964.).

- ↑ Johannes Istdahl Austgulen: Ethiopia: Experiences and Challenges . 2nd Edition. Books on Demand, Stockholm 2016, pp. 20 .

- ↑ Mekuria Bulcha: Oromo Writing . 1995, p. 38 (Other spelling: Imkullu).

- ↑ Mekuria Bulcha: Oromo Writing . 1995, p. 37 .

- ↑ Kebede Hordofa Janko: Missionaries, enslaved Oroma . 2005, p. 72 .

- ↑ Mekuria Bulcha: Oromo Writing . 1995, p. 41 (In fact, a new translation was not started until the 1970s.).

- ↑ a b Mekuria Bulcha: Oromo Writing . 1995, p. 42 (According to Senai W. Andemariam there were about 6000 entries. The difference is probably explained by whether only the roots or also the vocabulary derived from them are counted.).

- ↑ Mekuria Bulcha: Oromo Writing . 1995, p. 39-40 .

- ↑ Kebede Hordofa Janko: Missionaries, enslaved Oromo . 2005, p. 71 .

- ↑ a b Mekuria Bulcha: Oromo Writing . 1995, p. 48 .

- ↑ Melkamu Dunfa Borcha: The Roles and Status of Women in the Holistic Services of the Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus in Three Weredas of Western Wollega zone. (PDF) (No longer available online.) P. 24 , archived from the original on February 13, 2018 ; accessed on February 12, 2018 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ganno, Aster |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gannoo, Aster |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Ethiopian Oromo and Bible translator |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1874 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Illubabor |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1962 |

| Place of death | Nekemte , Wollega , Ethiopia |