Foreign trade profit

As gains from trade in are international trade theory those benefits referred to by international trade arise. These advantages can relate to the entire world economy , individual nations or national economies or individual population groups.

Foreign trade profits can always be realized if

- different countries differ in the availability of certain production factors or use different production processes

- positive economies of scale result from the expansion of the market

- through technology transfer are available new or improved technologies.

The term foreign trade profit comes from real international economic theory. It must be clearly delimited from the trade surplus , i.e. the excess from exports over imports , a term from the trade balance .

Causes of Foreign Trade Profits

There are various specific models in foreign trade theory that are intended to explain why countries trade with one another and how which foreign trade profits arise from them. However, for a more in-depth understanding, the theoretical model of an economy without foreign trade ( autarky ) is considered first, before special theories are discussed.

The theoretical models considered use the following simplifying assumptions:

- Only two countries are examined.

- Only two goods are produced (and consumed).

- There are no transport costs for the transfer of goods between countries.

- There is complete competition in both countries.

- The prices for the two goods are given as relative prices; H. there is no money and therefore no exchange rates.

Self-sufficiency

A self-sufficient economy, which in reality cannot be found in perfection, serves as a benchmark to explain the advantages of foreign trade. Such a country does not engage in foreign trade, i. H. it can only consume what it produces or it only produces what it consumes. Such a country has fixed consumption possibilities and thus a fixed production possibilities curve . It can only dispose of the amount of goods that are below or to the left or exactly on the transformation curve. To simplify matters, one often only considers one production factor, namely the total labor supply L and given labor productivity a L (see Fig. 1).

Foreign trade profits cannot therefore be realized in a self-sufficient economy.

Trade profits

The mere fact that foreign trade is being carried out leads to an expansion of consumption possibilities. With unchanged production quantities, one country trades in the products for which it has relative production advantages. Since these products are by nature products for which the other country has relative production disadvantages, the other country in turn trades them against products for which it itself has comparative advantages. This results in a new relative price ratio on the world market that is more favorable for the country with the respective comparative disadvantage than the production costs (= opportunity costs ) in one's own country. The consumption opportunities in both countries are increasing. In short: just through an international redistribution of existing goods, i. H. without changing the structure of production, there is an increase in welfare.

Specialization gains

This trade profit effect is strengthened or optimized through the international division of labor in the form of specialization of the individual economies in the very products for which they have a relative productivity advantage. Specialization means the redistribution of the production factor labor, i. H. if a country only produces the products with the comparatively lower opportunity costs. This is tantamount to a shift in production to the relatively expensive good in free trade, which then becomes an export good (see resource allocation ). Example: Country A specializes in Good because of its comparative advantage over Country B i . Country A can now obtain a higher price for this on the world market, while it has lower opportunity costs than country B for its production. At the same time, country B pays a lower price of goods for i on the world market than it would have if it had produced its own opportunity costs. There is an overall expansion of world production, which is more pronounced than with pure exchange (trade profits). One speaks of specialization gains. It should be noted at this point that the above considerations are based on the premise of complete specialization, i.e. H. both countries produce only one good. In the event that the total demand for one good exceeds the production capabilities of the country specializing in this good, the other country is forced to produce both goods. In addition to the good in which it specializes, this country must also produce the other good; there is incomplete specialization. The free trade price ratio is identical to the self-sufficiency price ratio that results in the country that produces both goods. In this case there is a change in the production structure in this country, but no foreign trade profits whatsoever.

Specialization due to productivity differences in the Ricardo model

The Ricardo model attributes foreign trade gains solely to differences in productivity in individual economies. The decisive factor here is not the absolute production advantages that a country has, but the comparative advantages .

Countries specialize in the production of goods which they can produce relatively cheaper than the other country if they are self-sufficient. Absolute production disadvantages, such as backward production technologies or an overall (absolute) lower productivity , do not affect this statement. The advantages of foreign trade depend solely on the difference in the relative price ratios between domestic and foreign countries. In other words, the greatest possible quantitative supply of goods for individual economies and for all nations can be achieved with foreign trade if each country specializes in the production of goods for which it has comparative cost advantages. These goods can be exchanged internationally for goods that can only be produced domestically with comparative cost disadvantages.

In order to make it clear that this specialization of the individual economies can result in foreign trade profits, an explanation about the "indirect production" of one country for the other country is advisable. Indirect production can be understood as meaning that one country purchases goods produced by the other country instead of producing them itself. Suppose we consider two economies: Country A and Country B, which can each produce two different goods, good i and good j . Furthermore, both countries can trade with each other. Country A could produce good j directly, but assuming that if country A has a comparative advantage over good i , it will specialize in it. Trade with country B enables country A to “produce” good j and thus to obtain it from country B at a relatively cheaper price. This indirect “production” is more efficient than direct.

| Good i | Good j | |

|---|---|---|

| Country A | a Li = 1 h per unit | a * Lj = 2 h per unit |

| Country B | a Li = 6 h per unit | a * Lj = 3 h per unit |

Example: The prerequisite is a relative price of good i , which should be 1 in the case of international equilibrium. If good i trades at the same price as good j , both countries will specialize. In this example, the work coefficients of good i should be 1 hour per unit in country A and 6 hours per unit in country B. Similarly for good j in country A are 2 hours per unit and in country B 3 hours per unit. In country A, the production of one unit of good i takes half as many hours as the production of one unit of good j . Workers in country A can earn more by producing a unit of good i and country A will specialize in good i . Conversely, in country B it takes twice as many hours to produce a unit of good i as it does to produce a unit of good j , so workers in country B can earn more from good j and country B will specialize in good j . Country A can “produce” good j more efficiently by producing good i and exchanging it for good j instead of producing good j itself. Should country A produce good j , it only produces half a unit per hour. Country A could use this hour to produce a whole unit of good i and exchange it for a whole unit of good j (remember: the price ratio is 1: 1). Country A wins on this trade. Correspondingly, country B could produce 1/6 unit of good i in one hour . However, it is better to spend this hour producing good j (1/3 unit per hour), which can then be exchanged for 1/3 unit of good i. Both countries can use their work twice as efficiently if they obtain the goods they need through mutual trade. In-house production would be less efficient.

Foreign trade profits arise from the different availability of certain production factors or different production processes used in the countries under consideration.

Specialization due to different factors in the Heckscher-Ohlin model

In the Heckscher-Ohlin model , the different relative factor endowments or resource distribution and the relative factor intensity of the individual nations are considered to be the cause of foreign trade and thus foreign trade profits. I.e. What matters is the existence of various production factors and their corresponding use. Relative productivity differences (technological conditions, work coefficients ...) are irrelevant.

In the Heckscher-Ohlin model, only two countries with two production factors are considered: labor and land . A comparative production advantage for a country results from the relatively more intensive use of the relatively more existing production factor. I.e. one country has cost and thus production advantages for certain goods due to its relatively higher labor or land supply compared to another. These goods are then called land-intensive or labor-intensive. In the respective factor markets, prices are formed by means of supply and demand for labor and land.

By taking up foreign trade, specialization comes about in the good for which the degree of utilization of the abundant factor is relatively higher. These land- or labor-intensive products are traded with another country, in which the relationship between factor distribution and usage intensity has just been reversed.

Example: Country A has a relatively higher supply of labor than country B. Consequently, country B has a relatively more abundant supply of land. Labor is therefore relatively cheaper in country A than in country B, and land is relatively cheaper in country B than in country A. Therefore, country A should specialize in the production of labor-intensive goods and country B in the production of land-intensive goods.

Thus, there is only one national shift in demand in both countries: demand for the relatively more available factor increases and that for the relatively scarcer factor decreases.

- Example: The specialization of country A in the more labor-intensive good increases the demand for labor in country A. In country B, the specialization in the land-intensive commodity increases the demand for land. As the demand increases, the price for the factors will increase.

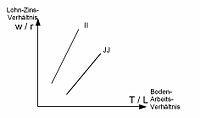

An increase in the price of the land or labor-intensive commodity leads to a simultaneous change in the wage-interest ratio within the individual countries. This redistribution of income means that there will be winners and losers:

- Those who get their factor income from the relatively more available factor gain from free trade, while those who get their income from the relatively scarce factor lose.

- Example: If the relative price for the more labor-intensive good i increases , there is a relative increase in wages for the workers and, at the same time, a decrease in the interest rate (rent and lease income, income from the sale of raw materials, etc.) for the landowners. The ratio w / r increases.

- Graphics to illustrate the Heckscher-Ohlin model

In theory, however, the “losers” could be compensated. This takes place in an international adjustment of the factor price ratios (see factor price equalization theorem ).

Without foreign trade, an economy would have to be completely self-sufficient. The country's consumption point would then be on the production possibilities curve (see Fig. 7 point 1 or 2). Point 1 corresponds to the optimal production and consumption quantity for a given budget.

If now foreign trade is carried out, an economy can consume more of both goods. The relation is again determined by the budget line of the country. The slope of this straight line corresponds exactly to the negative relative price ratio of good i to good j (= −Pi / Pj). The blue area in the graphic represents the possible increase in consumption based on point 2. Every point below or on the consumption possibility curve could now be consumed. As a result, it is theoretically possible that all economic agents in an economy can consume more. Foreign trade is thus a potential source of profit for all.

Other causes of foreign trade profits

In addition to the two theories by Ricardo and Heckscher-Ohlin mentioned above, there are other reasons for foreign trade profits, which, however, are of secondary importance. Three are listed here as examples:

Economies of scale

Economies of scale from expanding the market can also lead to foreign trade profits. In particular, this includes inter-industrial trade and intra-industrial trade.

In the case of intra- industrial trade , the industrial goods of the same product group are exported or imported in the two partner countries. The concrete advantage of intra-industrial trade consists in a greater benefit through additional and higher quality input on the domestic market for consumers and producers. The consumer has a greater choice of different products on the market, and prices also fall due to increasing economies of scale . Inter- industrial trade , on the other hand, refers to the exchange of industrial goods for different product groups. The trade in the various products takes place either in the form of export or import in the partner countries or within a country between the individual branches of industry.

Technology transfer

Furthermore, foreign trade activity brings with it so-called technology spillovers, i. H. various technologically less developed countries benefit from the know-how of more highly technical countries. Part of this principle is to penetrate the world market with known goods and technologies. This is particularly the case with automobiles and electronic products. This "reverse engineering" ("backward construction" / reconstruction) would not be possible without integration into the global goods trade.

Example: India's agriculture, and with it the Indian population, benefited from Germany's field cultivation techniques. Another example would be the expensive drinking water treatment of industrialized countries in developing countries, especially in arid areas with a relatively high population density.

The welfare increases achieved from foreign trade can in turn lead to better equipment in the research and development sector, which contributes to further development of production techniques and thus to an increase in productivity.

Summary

Two elementary foreign trade theories - the Ricardo model and the Heckscher-Ohlin model - offer explanations for the advantages that can be drawn from international trade. In the Ricardo model, both countries gain from foreign trade due to relative productivity advantages. So it's a win-win situation. In the Heckscher-Ohlin model, on the other hand, there are winners and losers from foreign trade.

In response to this fact, some countries are actually taking protectionist measures, such as the introduction of tariffs . Such protectionism helps the factor that is used relatively abundantly in the protected sector. Conversely, this policy harms the other factor. All in all, however, the gains apparently outweigh the losses, as otherwise the economies would not engage in foreign trade. Foreign trade gains are reflected in an increase in consumption opportunities, an increase in utility or an increase in welfare . With free trade , the potential foreign trade profits can be fully exploited. In the two models explained, foreign trade profits are defined as trade profits and specialization profits. The modeled foreign trade profits are based on a relative price ratio that can change over time. The terms of trade measure the change in the relative price level between export goods and imported goods in the long term.

See also

literature

- Gustav Dieckheuer: International economic relations . 5th edition. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2001, ISBN 3-486-25806-0 , p. 50, books.google.de

- Dixit, Norman: Foreign Trade Theory . 4th edition. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 1998, ISBN 3-486-24755-7

- Farmer, Wendner: Growth and Foreign Trade. An introduction to the equilibrium theory of growth and foreign trade dynamics . 2nd Edition. Physica-Verlag, Heidelberg 1999, ISBN 3-7908-1238-2

- Krugman, Obstfeld: International Economy: Theory and Politics of Foreign Trade . 7th edition. Pearson Studies, 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7199-6 , Chapter 3, Chapter 4

Web links

- H. Dawid: Lecture notes (PDF) Bielefeld University

- Jürgen Jerger: Lecture notes WS 06/07 ( Memento from May 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 6.7 MB) University of Regensburg

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jürgen Jerger: Lecture notes WS 06/07 ( Memento from May 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) University of Regensburg, p. 28

- ↑ Jürgen Jerger: Lecture notes WS 06/07 ( Memento from May 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) University of Regensburg, p. 67 ff.

- ↑ Gustav Dieck Heuer: International Economic Relations; 5th edition, page 50; Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag; 2001; ISBN 3-486-25806-0

- ↑ a b Krugman, Obstfeld: International Economics: Theory and Policy of Foreign Trade . 7th edition. Pearson Studies, 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7199-6

- ^ H. Dawid: Lecture notes, Bielefeld University, p. 39