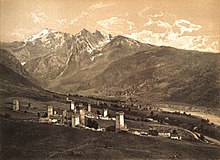

Mountain villages of Upper Svaneti

The mountain villages of Upper Svaneti in northwest Georgia have a number of architectural peculiarities, which is why Ushguli ( Georgian უშგული, Ushguli) as one of these villages, strictly speaking exclusively the district of Tschaschaschi (ჩაჟაში, Chazhashi) with an area of 1.09 hectares, became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996 was declared. During the time of the Soviet Union, this district had been protected as the Ushguli-Tschaschaschi Museum since 1971. In addition, there are 19.16 hectares of buffer zone, which includes the other districts of Ushguli with the preserved historical buildings and the cultural landscape used by mountain farmers (dairy and beef cattle farming and potato cultivation).

According to the assessment of the UNESCO commission, the mountain villages of Upper Svaneti, where they are largely intact, represent a cultural area in which the architecture of medieval origin combines in a unique way with an impressive, authentic mountain landscape. With the exception of Chaschi, these are not part of the world cultural heritage. Thanks to traditional forms of land use, according to the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), the connection between architecture and cultural landscape (criterion IV for cultural heritage according to UNESCO statutes) has only been preserved in an ideal-typical way in Tschaschaschi. The World Heritage status is closely linked to other authentic features of traditional Svanetian life (criterion V for cultural heritage UNESCO statutes), which are seen as a guarantee for the preservation of the existing human-environment relationship.

The mountain villages of Upper Svaneti are located in the Enguri Valley in the Greater Caucasus and its side valleys. According to the Tourism Center Mestia, Mestia , the administrative center of Upper Svaneti, is seeing steadily increasing visitor numbers (from under 9,000 in 2011 to over 26,000 in 2014) due to its rich cultural and ecological heritage.

The mountain villages Kala, Khalde, Ipari, Tsvirmi and Ieli lie along the Enguri, downstream from Ushguli. The course of the Adishchala coming from the Adishi Glacier meets the Enguri in the mountain village of Ipari. Enguri and Mulkhura meet at the village of Latali. From there you get upstream along the Mulkhura to Mestia, behind Mestia is the mountain village of Mulakhi.

Ushguli , usually visited on day trips from Mestia, is the main destination for tourists traveling to Upper Svaneti. At 2200 m above sea level at its highest point, the village community is considered to be one of the highest permanently populated places in Europe. Within sight of the village is the highest mountain in Georgia, the Shchara with a height of 5201 meters, whose glacier can be reached from Ushguli in about three hours on foot or by horse.

Architectural features

Defense towers

The medieval defense towers, which can be found in different frequencies in almost all mountain villages, represent an architectural feature of the villages. These towers have up to five floors, with the upper floors mainly used for defensive purposes. For this purpose, on most of these towers there are defensive oriels with so-called machicolation , which were used to douse attacking enemies with pitch . Certainly, the number of towers also always represented the power of individual communities of descent. On the top of the tower, which tapers slightly in the shape of a circular arc for static reasons, there is a roof structure made of wooden beams, which forms a gable roof. The towers without parapets from which the buildings could be defended have gable roofs or flat roofs sloping to one side. The roofs of all towers are covered with slate, some of them are accessible via terrace-like structures. The towers, which are less powerful, but just as tall, presumably also performed surveillance functions or served as a last resort in the event of a defense.

Around these towers there are special houses, so-called machubis , which usually had two floors. In these lived humans and animals. From the upper floor of the Machubis , the Darzabi , there is, in the event that it is directly connected to a tower, there is an entrance to the tower, into which the population could retreat in the event of an enemy attack. In the Ushguli village alone, UNESCO has around 200 historical buildings. However, many similar facilities in the region have fallen into disrepair or destroyed, and in Ushguli, too, the existence of historical buildings is seriously endangered.

The interior of the four to five-storey towers with an average external area of five by five meters also reveals uses as a granary and warehouse and also as temporary living space with cooking facilities. The ground floor and, in some of the mighty towers, the first floor on top of it reveal a further special structural feature: they contain brick-lined pointed floor vaulted ceilings that give the impression that you are in a small house. In this way, the enormous forces of the heavy structures are diverted to the approximately one meter thick, in some places even more powerful outer walls and into the foundation, which additionally increases the stability of the defense towers. Some towers contain concealed stone stairs that run inside, which - for reasons of defense - separate the ground floor from the upper floors. B. by access from the outside. With others, the first floor can only be reached through a retractable wooden ladder.

Machubi

The Machubi is the second structure that is typical of the mountain villages in Upper Svaneti . It consists of two floors, with the ground or first floor as winter dwelling housing both humans and animals in order to use the body heat of all living beings for the cold winters. In the center of the building was the flue-free fireplace, which was covered by a wooden hanging device on which slate slabs lay. These prevented the flames from reaching the floor above, the Darzabi , where hay was stored for the animals and food for the people in winter.

The flat gable roof of the stone building, which is built without rafters only from transverse beams, is covered with slates. Their heavy load increases in winter due to the layer of snow on top, which also acts as an insulation layer. In the center, the roof is supported by a massive wooden column, on which the superimposed beams create a triangular shape that follows the angle of the gable roof. It is absorbed by the weight on the beams and diverted into the vertical of the central wooden column.

Depending on the size of the building, the ground floor contained a two- to three-story wooden installation on up to four sides, which resembles a continuous bunk bed or a very deep shelving system that is paneled towards the front. At the bottom in winter were the cows, whose heads protruded through openings to the feed troughs in front. On the next level there were sheep, goats and cattle like chickens, on the top level people's beds were attached. The entire construction, which is still preserved in many machubis of the mountain villages of Upper Svaneti, is richly decorated with carvings that, depending on the design and quality, indicate the prosperity of the families. Around the fireplace there were other pieces of furniture on the floor lined with slate, such as wooden armchairs for the head of the family ( makhushi ), benches, shelves, cradles for newborns and toddlers or objects for weaving, spinning, tool and furniture making, etc. Today, Ushguli presents itself a Machubi as an ethnographic museum, which is equipped with many original objects, at the top in the district of Schibiani (Chibiani / Zhibiani). The life of the families took place over the course of the year, alternating between machubis, towers and pure stable buildings.

Residential tower, fortified house or tower house

A building type that occurs only in Ushguli is referred to in the literature as a fortified house , residential tower or tower house . From the outside, similar to the towers, with at least three storeys and a weir core under the roof structure of the third or fourth storey, this is wider and deeper than that. The interiors follow the example of the Machubis, which contain protective systems with combinations of internal and external stairs.

All three types of buildings are constructed from irregular cuboids and slabs of limestone and slate, combined with lime and sand-based mortar. Some of the towers still have remnants of lime plaster, but most of them show the multicolored pattern of their stone shell on the surface.

Sacred buildings

In the 6th century Christianity came to the region, so that the first sacred buildings were built in the places . There are many ornate medieval wall paintings in the Church of the Savior in Ushguli. In Zhibiani (Chibiani) there is a church with paintings from the Renaissance period . Svaneti was associated with the Georgian empires throughout the Middle Ages, despite its remote location. The most important icon for devout Swans can be found in the village of Kala. In Upper Svaneti alone, over 100 Georgian Orthodox churches were built in the Middle Ages , most of them at the height of church architecture between the 9th and 13th centuries.

Historical references

The first written mention of the villages was made by the Greek geographer Strabo in the 1st century BC. The region had been a vassal state of the Kingdom of Lasika since the 4th century BC . In the 6th century AD, the region was increasingly Christianized, but pagan rituals continued to play an important role in the religious life of the people of Svaneti. From the 12th century AD Svaneti was part of the United Kingdom of Georgia. This experienced its so-called golden age between the 11th and 13th centuries. With the break-in of Mongolian forces, the Georgian kingdom increasingly split into many regional domains with individual feudal lords. In the 15th century, in addition to the Principality of Dadeschkeliani- Svaneti in western Upper Svaneti , the Principality of Lower Svaneti ( Dadiani- Svaneti ) and the so-called Free Svaneti in eastern Upper Svaneti , which include the mountain villages of Upper Svaneti , were established. At that time they enjoyed a high degree of autonomy, since there no specific family had the upper hand over the organization of political and economic conditions.

In 1864 Upper Svanetia and its mountain villages were annexed to the Russian Empire. Even before, under the influence of the Russian Empire on other regions of Georgia and Lower Svaneti ( Caucasus War 1817–1864 ), attempts were made to take action against traditional legal and life ideas that were widespread throughout Georgia and especially in the mountain villages of Upper Svaneti, even during the short period During the Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918–1921) there were strong efforts to combat the community assemblies, councils of elders and mediation courts typical of all of Svaneti because they opposed the modernization of society and the implementation of central law.

During the time of the Soviet Union, these efforts were continued with measures to implement the Marxist-Leninist ideology in order to change the way of life that was perceived as archaic and backward, especially in the mountain regions. The architecture of the mountain villages was also heavily influenced here. So towers were demolished as symbols of an archaic time in order to build administrative and utility buildings of the newly founded kolkhozes and sovkhozes (including schools, hospitals, shops) and thus make clear the dawn of the new era in architecture.

Above all, structural elements originate from this time that are reminiscent of an elegant and spacious dacha architecture typical of the Soviet Union with prefabricated, closed balconies in Georgian style, from which the rooms, which are usually in a row, can be reached. This also applied to the newly built residential buildings with large windows and built-in, glazed terraces that let light and warmth into the house and thus ended life in the smoky rooms. However, it must be stated that for the area around Mestia, balcony-like wooden porches of older date can also be found in the photographs of the Italian mountaineer and photographer Vittorio Sella .

During the ecological catastrophe in the winter of 1986/87, which was caused by persistent, unusually heavy snowfall, 80 to 100 people died in Upper and Lower Svaneti, depending on the sources, and a large number of historical buildings were also destroyed. As a result, around 16,000 people were permanently resettled in other regions of Georgia, mainly in villages in Kvemo Kartli , south of Tbilisi.

Current developments

There are two reasons why the number of towers in Upper Svaneti is declining without showing a pronounced ruin structure: On the one hand, the building material from collapsed towers or other buildings has always been used to construct new buildings and to expand old ones. Because it had been obtained with great effort by previous generations - here the different mortars based on lime or cement also provide information about different construction phases.

Due to structural changes through human activity (especially for tourist accommodation) or the destruction of the architectural heritage through natural events such as avalanches and landslides, there is still a progressive loss of historical building fabric.

In order to maintain the entire cultural landscape within the framework of sustainable or gentle tourism, which creates income opportunities for the local population, a management plan for the villages of Upper Svaneti is required on the part of the Georgian state. Local administration and above all the local population must be involved. This applies above all to the Ushguli village community, as the entire mention of the region under the tourist-attractive label of world cultural heritage depends on the district of Tschaschaschi (Chazhashi) and the buffer zone surrounding it. Because construction and maintenance measures are not financially supported by UNESCO and the Georgian state seems to have largely lacked the means to support the local population in preserving the buildings outside of the UNESCO-awarded district of Tschaschaschi.

With the ongoing construction of the highway from Zugdidi ( Georgian ზუგდიდი, Zugdidi) via Mestia, Ushguli and the Latpari Pass to Lentechi (Georgian ლენტეხი, Lentekhi), an increasingly better development of the mountain villages of Upper Svaneti can be expected, which in addition to an improvement in the However, local living conditions will also lead to significant changes in the cultural landscape.

literature

- Wolfgang Korall: Svaneti - farewell to time . Kraft, Würzburg 1991, ISBN 3-8083-2005-2 .

- Vinzenzo Pavan: Svaneti Towers, Fortified Stone Villages in the Caucasus . In Glocal Stone. VeronaFiere - 46th Marmomacc Fair, 2011. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Brigitta Schrade: Treasury of Svaneti: The restoration program of Stichting Horizon 1997-2006 in Georgia (with photos by Rolf Schrade) / Art treasury of Svaneti: The restoration program of Stichting Horizon in Georgia (with photos by Rolf Schrade) . Stichting Horizon, Rolf Schrade, Naarden / Netherlands, Mahlow near Berlin 2008.

Web links

- Stefan Applis: Website with information on Upper Svaneti (world cultural heritage, tourism, traditional and modern culture) , especially on the upper Enguri valley with Ushguli as the end and starting point for hikes to the Shchara; (= university research project in Ushguli, Justus Liebig University Gießen and the Institute for Conflict Research at the University of Marburg in cooperation with the Georgian National Museum and its sub-museum in Mestia, the Museum of Ethnography and History of Svaneti).

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- Helmuth Weiss: World Heritage Online website with information on all World Heritage Sites. Information on Svaneti .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Stefan Applis: Ushguli | The architectural world cultural heritage of Svaneti - an overview. In: https://stefan-applis.geographien.com . 2019, accessed May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ UNESCO: World Heritage List - Upper Svanetia. UNESCO, 1996, accessed May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d Vinzenzo Pavan: Svaneti Towers, Fortified Stone Villages in the Caucasus. Glocal Stone. Verona Fiere - 46th Marmomacc Fair, 2011, accessed May 5, 2019 .

- ^ The Criteria for Selection. UNESCO - World Heritage Center, accessed May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Stefan Applis: Greater Caucasus | The mountain villages of Upper Svaneti in Georgia | An overview. In: https://stefan-applis-geographien.com/ . 2019, accessed May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Marianna Cuppucci and Luca Zarilli: New trends in mountain and heritage tourism: The case of upper Svaneti in the context of Georgian tourist sector. In: Researchgate. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites 15 (1), 65-78, 2015, accessed on May 5, 2019 .

- Jump up ↑ Nana Bolashvili, Andreas Dittmann, Lorenz King and Vazha Neidze: National Atlas of Georgia . Ed .: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Vakhushti Begationi Institute of Geography and Justus Liebig University of Giessen, Institute of Geography. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2018, p. 71 .

- ↑ Antoni Tarragüel: Developing an approach for analyzing the possible impact of natural hazards on cultural heritage: a case study in the Upper Svaneti region of Georgia. Thesis paper. University of Twente. Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation, 87-92, 2011, accessed May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Georgia - world cultural heritage online - mountain villages of Upper Svaneti in detail. Retrieved August 16, 2017 .

- ↑ Stéphane Voell: Traditional Law in the Caucasus . Local Legal Practices in the Georgian Lowlands. In: Curupira Workshop . tape 20 . Curupira: Förderverein Kultur- und Sozialanthropologie in Marburg eV, Marburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-8185-0524-0 , p. 110 ff . ( academia.edu ).

- ↑ Kevin Tuite: Lightning, Sacrifice, and Possession in the Traditional Religions of the Caucasus. Introduction. In: Anthropos 99 (2), 481- 497. University of Montréal, 2004, accessed on May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Stéphane Voell: Traditional Law in the Caucasus . Local Legal Practices in the Georgian Lowlands. In: Curupira Workshop . tape 20 . Curupira: Förderverein Kultur- und Sozialanthropologie in Marburg eV, Marburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-8185-0524-0 , p. 22-26 ( academia.edu ).

- ↑ Stéphane Voell: Traditional Law in the Caucasus . Local Legal Practices in the Georgian Lowlands. In: Curupira Workshop . tape 20 . Curupira: Förderverein Kultur- und Sozialanthropologie in Marburg eV, Marburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-8185-0524-0 , p. 89 ( academia.edu ).

- ↑ a b Stefan Applis: Ushguli | Towers, mountains, hammer & sickle - what is part of the cultural heritage of the Ushguli village community in Georgia? In: https://stefan-applis-geographien.com/ . 2015, accessed May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Stéphane Voell: Traditional Law in the Caucasus . Local Legal Practices in the Georgian Lowlands. In: Curupira Workshop . tape 20 . Curupira: Förderverein Kultur- und Sozialanthropologie in Marburg eV, Marburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-8185-0524-0 , p. 90-96 ( academia.edu ).

- ↑ a b Stefan Applis: Perspectives | Tourism sustains, and threatens, Georgia's highland heritage. In: Eurasianet.org. 2018, accessed on May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Stefan Applis: Structural changes in Ushguli. In: https://stefan-applis-geographien.com/ . 2018, accessed May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Antoni Alcaraz Tarragüel: Developing an approach for analyzing the possible impact of natural hazards on cultural heritage: a case study in the Upper Svaneti region of Georgia. Thesis paper. University of Twente. Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation, 2011, accessed on May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Lela Khartishvili, Andreas Muhar, Thomas Dax and Ioseb Khelashvili: Rural tourism in Georgia in transition: challenges for regional sustainability. In: Sustainability 11 (2). Researchgate, 2019, accessed May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Eric Engel, Henrica von der Behrens, Dorian Frieden, Karen Möhring, Constanze Schaaff, Philipp Tepper, Ulrike Müller and Siddarth Prakash: Strategic Options towards Sustainable Development in Mountainous Regions. A Case Study on Zemo Svaneti, Georgia. SLE Publication Series, Faculty of Agriculture and Horticulture. Mestia, Berlin, 2006, accessed on May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Jörg Stadelbauer: Protect or use? Conflicts over the agricultural heritage in Georgia . In: Eastern Europe (Ed.): Dreamland Georgia. Interpretations of culture and politics . tape 68 , no. 7 , 2018, p. 57 .

- ↑ Asian Development Bank: Sustainable Urban Transport Investment Program: Rehabilitation and Reconstruction of Secondary Road Zugdidi-Jvari-Mestia-Lasdili Road. 2010, accessed on May 5, 2019 .