Christian Möllinger

Christian Möllinger (born September 26, 1754 in Neustadt an der Haardt , † January 24, 1826 in Berlin ) was a German Mennonite watchmaker and specialist author .

Life

Möllinger was born in Neustadt an der Haardt on September 26, 1754 as the son of the watchmaker Johann Jacob Möllinger and was destined to learn the art of watchmaking with seven of his brothers. Christian Möllinger came to Berlin on his hikes . Around 1778 he was accepted into the workshop of the Berlin court watchmaker Christian Ernst Kleemeyer, in which the music boxes that were so popular at the time were made, and attracted the attention of experts with his excellent mechanical skill and precision in his work.

Apartments in Berlin Since his arrival in Berlin (1776/1778) Christian Möllinger lived in the Schlosser-Herberge, Jerusalemer Strasse at the corner of Zimmerstrasse.

- Leipziger Strasse in Berlin No. 86, 1799 Möllinger Hof-Uhrmacher 1801 dto. 1812

- Leipziger Strasse in Berlin No. 87, 1820 Mr. Möllinger court watchmaker

In the commercial plan of Berlin (1844) the clock factory Chr. Möllinger (Sohn) at Zimmerstrasse 88 is recorded.

Services

In 1780 he became a master and, as a masterpiece, made an eight-day weight watch with a date hand and indication of the changes in the moon without outside help. With this he established his reputation as an artistic clockmaker, which he also consolidated by making astronomical and other clocks of very complicated construction, which is why the Royal Prussian Academy of Arts and Mechanical Sciences appointed him an academic artist in 1787 .

The illustrated astronomical grandfather clock stood in the blue French hall in the city palace and can be viewed today in the south wing of the Marble Palace on Heiligensee in Potsdam. It has been restored and described in detail. It is a total of 326 cm high and has interchangeable play rollers, a flute mechanism and an astronomical clockwork with a leap year wheel that only turns every 400 years.

On August 14, 1790, Christian Möllinger was appointed chief clockmaker to the Prussian king.

Christian Möllinger made the clockwork of the old tower clock of the Sankt-Jacob-Kirche in Gingst auf Rügen and that of the church in Liebenwalde .

The academy clock

The most famous work is probably the academy clock commissioned by the astronomer Johann Elert Bode in 1787 and made by Christian Möllinger above the main portal of the academy building Unter den Linden. It was the first and until 1872 only public normal clock in Berlin. This clock was placed in the middle window of the academy. It produced excellent gait results, which is mainly due to the very carefully crafted rust pendulum . It was illuminated at night so that the exact time could be read at any time. The clock is 1.70 m high and had a 55 cm dial. It was in operation until 1844 and can now be viewed on Jägerstrasse.

Johann Elert Bode and his watchmaker

In the spring of 1787 Christian Möllinger Bode made a new suggestion: “Among other things, I made a large astronomical clock, which his father Jacob Möllinger had already made that came out in the Berlin monthly in the piece, so in January of last year, and Mr. Oberkonsistorialrat Silberschlag as the author has been praised as a particularly artistic work. This piece of course cost me a lot of work, but in the opinion of Kenner it should be a work that deserves a place at the Academy of Sciences because of its rarity with a lot of mechanical work. "He suggests that the watch be in its" bad To visit the apartment [in the locksmith's hostel] and if I got it paid like that, I would be able to spend even more time on works of art of this kind and to waste all my energies, the glory of my present fatherland in view of this To spread art more and more ”. In a letter 90 days later, Christian Möllinger submitted a proposal for a watch for the Academy of Sciences.

Christian Möllinger's offer

“To the best of my knowledge, I cannot but approve of Mr. Möllinger's suggestions and information, and I am fully assured in advance that this artist will deliver a very beautiful work and entirely in accordance with the intentions that will increase the academy and its great honor and I find the price for such a watch, along with its installation and mounting, moderate. Mr Möllinger believes that he is not allowed to add a striking mechanism to these watches, with which I fully agree, because it would make the watch considerably more expensive and, on the other hand, would not provide the benefit indicated for this great expense, because the low level of the watch means that the strikes are only close by Neighborhood around would be able to hear. "

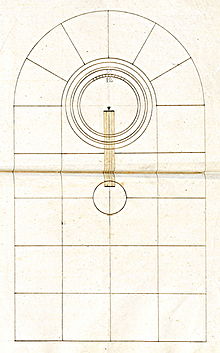

The offer from Christian Möllinger Großuhrmacher; Berlin, May 22nd 1787: From an astronomical clock which the Royal Academy decided to have made. A clock is supposed to be installed in or above the medium-sized portal window of the academy so that the public receives a timepiece, according to which all public and private clocks can be set reliably.

- Since the movement can best be found in the rounding of the portal window, as in the upcoming presentation of the window and dial, the clarity and symmetry require dial 2 to be 6 inches.

- For precise regulation of the clock, it is extremely necessary that the same point seconds in the middle.

- Should that be appropriate in the long run and the size of the way. So the size and proportion of the wheels are both required, as the following outline shows.

- But since it would be awkward to have a clock in the hall and still not be able to see how much time is and it is necessary for the position of the wise men to follow the course of the sun, the work in the hall is even on a small wise sheet of paper even show hours, minutes and seconds in a concentrated manner as if by heart, even the outer wise men can be directed precisely to the inner ones.

- Because the work is alternately exposed to heat and cold, a Harizony Perpendicul ( rust pendulum ) of 9 metal rods is necessary.

- The clock will show the hour minutes and seconds in the middle on a white dial painted like Aimalyen with black German numbers through the fire outside the window .

- It will perform the same services internally on a smaller one.

- She will walk for 8 days and go away while being drawn up.

- It is given an artificial Perpendicul stick with a large and iron button.

- It is made dust-proof, simple and clean, everything that can contribute to the beauty of the work can be used.

- And finally, at the manufacturer's expense, fastened and placed with well-attached iron rods, where the manufacturer makes himself obligatory to deliver between 3 and 4 months from the day of signing the work and set the price of two hundred Reichstaler.

- Berlin, May 22, 1787 Accorded by His Excellency Lord of the Royal Academy Count von Herzberg and appointed June 29, 1787

The clock had two English pewter dials with the numbers written in black; the larger one faced the street, the other one to the academy hall, to serve the watchmaker to check the accuracy. Both sides had four “wise men”, four steel hands, an hour, two minute and a second hand. Three of them were supposed to show the steady rate of the clock, the mean time in hours, minutes and seconds, and the fourth openwork minute hand with the gold-plated sun formation together with the hour hand, the true time with each sundial. This artificial invention of Christian Möllinger, as Bode explained in his scientific description of the chronometer, was first widely praised. The dial was also illuminated at night so that the audience could always read the time. The clockwork should be wound up once a week. The person responsible for its monitoring had to go to the observatory every Sunday to check the accuracy of his pocket watch based on the time, which was determined as a result of current sky observation. Then he regulated the academy clock. So the academy astronomer was responsible for the sky results. On October 16, 1787, Herzberg informed the magistrate that the new city clock had to be installed. He emphasized that the hard-working and skilful Professor Bode had taken over the supervision of the academy, so that both the “solar as well as the civil time” would be precisely specified. The city watchmakers should use these as a guide and visit them more often.

Heinrich Heine mentioned in a letter that the citizens of Berlin set their pocket watches according to this clock. Even Karl Gutzkow writes about the clock and compares it with the sundial by JE Bode.

Möllinger's academy clock and its fate

Christian Möllinger now had an introduction printed on half a sheet for the Berliners, which could be obtained for a penny for the benefit of a burned-down Ruppin watchmaker. Bode published a newspaper article. In it he explained in detail the so-called true and mean time and how the time coincides with the position and apparent course of the sun in the sky, so that it is always noon during the year when the sun is in the south. But the new timepiece had been hanging on the window for four weeks, and an important change had to be made. The problem of “true and mean time” dominated the discussion. Now, however, most of the audience had difficulties setting their own clock because of the double time determination of the dial. There should have been misunderstandings. The academy had to convene a conference of expert members. After lengthy deliberations, they decided to remove two hands from the outer dial and leave only the hour and minute hands, which indicate the true time after the sun. All four hands should remain on the inner sheet so that experts can see the full time in the hall.

Christian Möllinger had to experience another additional facility at that time. Since 1793, a large sundial attached underneath his clock has been used , as officially reported by connoisseurs, to prove whether that clock correctly indicates the difference between the mean clock and true solar time, since solar time can only be correct with the time four times a year , just like in Berlin some tower clocks on their south side were equipped with a sundial as a control. In December 1810 this was corrected at Bode's request; all clocks were finally set according to the mean time. Only then was Möllinger's pendulum clock able to take its satisfactory course from all sides.

In his text on the normal clock, Christian Möllinger suggested a signal with two flags for a uniform time indication that should reach all of Berlin from the Parochial Church at exactly 12 o'clock . The other leading tower clockmaker Carl Ludwig Buschberg then had a counter-writ distributed. It bore the militant title "Honor rescue of the Berlin tower clocks against the accusation of Möllinger" (Berlin 1799). But its academy clock became an unparalleled attraction. Travelers visited Prussia's residence and admired this "normal clock"

The first precisely regulated normal clocks were only set up in Berlin in 1872, in front of the Supreme Court, at Potsdamer Tor, Moritzplatz, Spittelmarkt, Hackescher Markt and at the Oranienburger Tor. They were connected by underground cables to the pendulum clock of the new observatory on Enckeplatz, which powered the movement, moved the hands and kept them in two-second increments.

Möllinger's chronometer, which fulfilled its task for Berlin and the people of Berlin for so many decades, survived until the demolition of the traditional academy building in 1903. The watch was removed and the large display dial facing the city also broke. Only the small dial has survived to this day.

In 1903 the court watchmaker Friedrich Tiede took the watch free of charge at Charlottenstrasse 49 for safekeeping. When his business was sold in February 1913, it went to court watchmaker Adolf Oppermann at Mohrenstrasse 20 and, since 1924, at Kronenstrasse 19.

The Prussian Academy of Sciences passed a resolution on 13 February 1930 that contained in the Oppermann business astronomical clock "to be taken by the Academy itself in custody" should. And a few weeks later, on March 13, 1930, the minutes of a meeting said: “The old normal clock is to be given to the Märkisches Museum on loan for safekeeping.” The tower clock factory CF Rochlitz agrees to repair the example without having to restore the broken record sheet and put it into operation, and estimated 175 Reichsmarks for the repair. The academy replied on April 1st that it would cover these costs if the Märkisches Museum agreed to keep the watch on loan in its house.

A major exhibition was planned for 1931; “New Berlin” the first Hall A with the title “Creative Hands, Workshops of the Spirit” was supposed to present “Examples of old Berlin watchmaking” in room 44 (especially noteworthy is the normal clock of the Academy, according to which all of Berlin has been based for over 100 years). The academy agreed and wanted to have the clock repaired quickly. Your letter of April 15, 1930 ended with the words: “After the exhibition is over, the academy asks you to keep this watch in safekeeping.” It is thanks to the Märkisches Museum and its employees that the watch was able to survive the following decades was not banished to a magazine or external depot, but could be viewed and studied by many visitors.

In 1997 the watch returned from the Märkisches Museum of the Stadtmuseum Foundation to its client and ancestral owner. The pendulum clock has been restored and made usable and could already be demonstrated in August and September 1997 on the occasion of the 350th anniversary of the street Unter den Linden in a large Linden exhibition in the building of the State Library in Berlin and thus near its former location. Your current location is the space in front of the archive reading room in Jägerstrasse 22, (Berlin-Mitte). In 2001 the clock was fundamentally restored and restarted by Mr Burkhard Schlänger from Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg. She has been regularly serviced and looked after by him ever since.

Picture gallery

Fonts

Möllinger's importance not only for Berlin watchmaking is due to the fact that he was the first Berlin specialist to publish small, independently developed publications on clocks and clock technology. The following writings are listed in the yearbooks and catalogs of that time:

- 1787: Nachr. Ve the true u. Mean time at the same time showing to d. Windows d. House d. Akad. D. Science clock set up in Berlin. 8. Berl. 787.

- 1798: About the gen. Complaints regarding this are irregular. Ganges b. Thurm clocks, etc. about d. Means of getting these clocks right without great expense. 8. Berl. 1798.

- 1817: Small clock catechism for the public, through which you can get a clear understanding of clocks and their facilities, and also remedy small errors yourself, published with 2 explanatory coppers and a comparison table, Berlin 1817

- 1823: Another proposal to set up a normal clock for Berlin

swell

- Secret State Archive of Prussian Cultural Heritage : Patent for the "court and academic watchmaker, Mr. Christian Möllinger" from August 1790.

- Friedhelm Schwemin: The Berlin astronomer: life and work of Johann Elert Bode 1747-1826. Acta Historica Astronomiae Vol. 30, Verlag Harri Deutsch, 2006. ISBN 3-8171-1796-5 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ In a letter to the Royal Prussian Academy of Arts and Mechanical Sciences

- ↑ Statistical information on the architecture and sociology of the owners and residents of the houses in the years 1785–1815

- ↑ Local history and monument preservation Berlin in the Kulturbund der DDR

- ↑ Spenerfchen newspaper dated February 9, 1826

- ↑ restoration report (PDF, 1.6 MB) by Kurt Kallensee, Potsdam

- ^ Genealogy of the Möllinger family ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) at thewatchmaker.eu, accessed on March 24, 2012

- ↑ Description ( memento of April 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) of the church in Liebenwalde, accessed on March 25, 2012

- ^ Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences Archive

- ^ Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences Archive

- ^ Heinrich Heine, Letters from Berlin, 1st letter, January 26, 1822

- ^ Karl Gutzkow : From the boyhood (1852) ; with a picture of the academy building

- ↑ Facsimile ( memento of April 13, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) of the font, accessed on March 25, 2012

- ↑ Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch 1821, pp. 244f. , Ed. Dr. JE Bode

- ^ Secret State Archives of Prussian Cultural Heritage: Rep. 76 old (older [religious] higher authorities), Dept. III. No 205: Acta Generalia concerning the appointment of academic artists and their privileges v: 1788-1810, unpag .: Patent for the "court and academic clockmaker, Mr. Christian Möllinger" from August 1790

- ↑ Friedhelm Schwemin, about the academy clock

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Möllinger, Christian |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German watchmaker |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 26, 1754 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Neustadt an der Weinstrasse |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 24, 1826 |

| Place of death | Berlin |