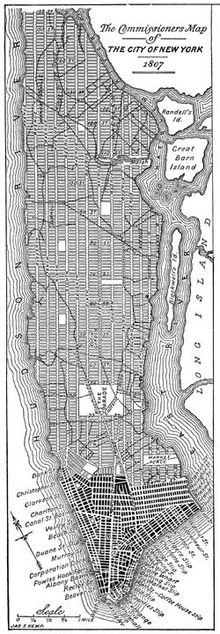

Commissioners' plan of 1811

The Commissioners' Plan of 1811 was a proposal by the New York State Government adopted in 1811 to complete the proper development and sale of land on Manhattan between 14th Street and Washington Heights . It divides the large, then sparsely populated part of the island into about 2000 long, narrow "blocks", rectangular plots of land drawn in an east-west direction. The complete Manhattan street blocks or the properties in between have an approximate dimension of 210 m by 60 m (the unit of length used for the measurement at that time was the foot with 12 inches; about 30.5 cm). This resulted in the 5 acre plots (20,228 m² each).

This plan is probably the most famous implementation of a grid plan ( planned city ) and is considered by many historians to be extremely visionary at the time of its creation. However, some have criticized its overly monotonous layout compared to the irregular street patterns of older cities. The plan was drawn up by a three-person commission made up of Governor Morris , attorney John Rutherfurd and surveyor Simeon De Witt .

A perfectly even network of streets and property lines was envisaged without taking the topography of Manhattan Island into consideration. Twelve consecutively numbered streets were planned (in this context referred to as avenues ), which should run in a north-south direction (in the broadest sense - Manhattan is slightly inclined in a northeast-southwest direction), largely parallel to the coastline of the Hudson River , and 155 streets crossing at right angles . The places where these intersecting roads were to run formed the boundaries of 5- acre parcels into which the land was previously divided.

The uniform grid

The twelve north-south oriented longitudinal streets were given names with the addition "Avenue" (up to 14th Street , the A-, B-, C-, D-avenue run as four more). The east-west aligned cross streets were generally given names with consecutive digits to the north and the addition "Street". They are numbered consecutively from the south from Bleecker / Houston Street with ordinal numbers from 1st to 184th in the north, level with the Bronx .

The 5th Avenue divides the cross-roads of East and West, each side its own, 5th from the Ave. house numbering in ascending order towards the island coast. For example, 10 East 42nd Street and 10 West 42nd Street are two different buildings. Central Park, originally not planned at all, is located on its north-south axis between 59th Street and 110th Street . 5th Avenue forms its eastern edge.

The exceptions in the system are the existing Broadway as the central axis up to Central Park, Times Square and the freeway-like, the island almost completely enclosing West Street (partly 10th, 11th and 12th avenues) and South Street or the FDR-Drive as the easternmost traffic axis. South of Houston Street, the naming was already completed and the plan will not change it.

Each avenue should be one hundred feet (about 30 meters) wide. The avenues in the center of the island should be 922 feet apart, and the avenues closer to the river bank should be a little closer together. At that time, it was assumed that the streets near the port facilities would be more frequented than those in the middle of the island, as the commercial and industrial centers were close to the water. A closer placement of the avenues there is an advantage from this point of view. The streets crossing in (relative) east-west direction were only intended to be 200 feet (approx. 61 m) apart, which is a lattice of about 2000 long, narrow ones Blocks in twelve pillars. Including the width of the cross streets is exactly 20 blocks a mile (1.6 km) away in the north-south direction.

It is worth noting that the vast Central Park , which now extends from 8th to 5th Avenues and 59th to 110th Streets, was not originally part of this plan, as no thought was given to it prior to 1853. There is much room for speculation about the level of development, house and population density, and importance that New York would have today if Central Park had never been established.

See also

- Randel Plan (after John Randel Jr.)

literature

- Hilary Ballon (Editor): The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811-2011. Self-published 2012 by the Museum of the City of New York (English)